Non-violence on display in Belarus

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/08/2020 (1941 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

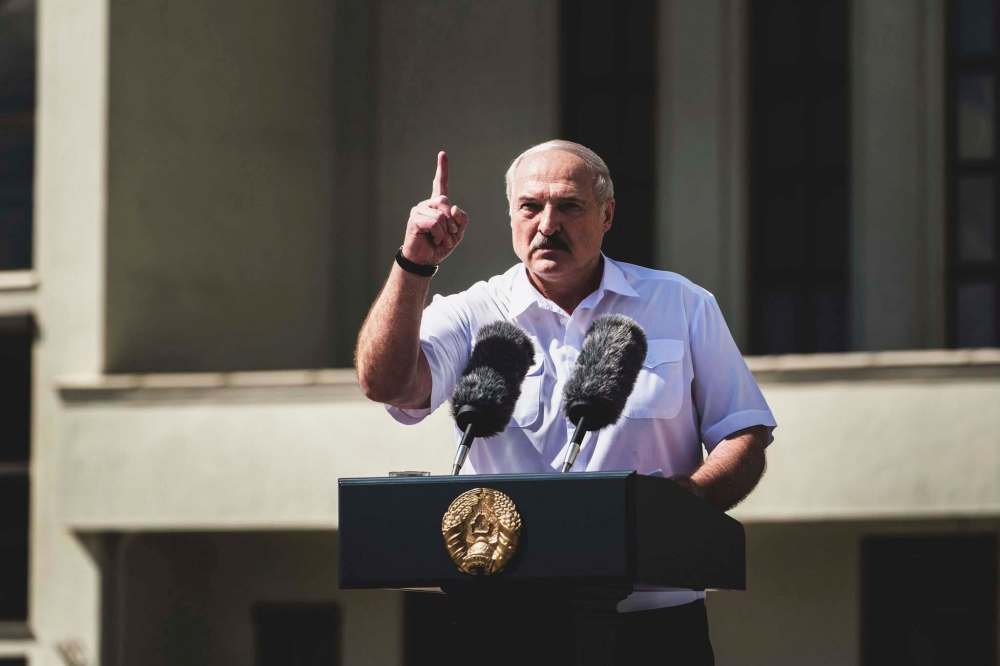

ON Monday, Belarusian strongman Alexander Lukashenko went to the Minsk Tractor Works, the country’s biggest factory with almost 15,000 workers, and did his tough-guy act: “Until you kill me, there will be no other election.” The horn-handed sons of toil simply replied by chanting “Ukhodi!” — Get out!

It looked like a restaging of the famous scene in Bucharest in 1989, when long-ruling Romanian Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu was shouted down by an enraged crowd. Like Ceauescu, Lukashenko faltered, amazed and bewildered — these people were supposed to be his “base” — and then fled the podium.

Ceausescu was dead within four days of his last speech, executed by his own colleagues. That probably won’t happen to Lukashenko: the Belarusian uprising is non-violent. Lukashenko is not a Communist, either, although his regime has been called “neo-Soviet.” But will he be gone in four days? Maybe so.

And maybe not, of course. There could be a Russian military intervention to prevent power from falling into the “wrong” hands, although that seems unlikely. Or Lukashenko might manage to persuade his demoralized “security” forces to do enough killing to clear the streets of the daily demonstrations, though that also seems improbable.

Or the change of regime could just take a bit longer: these things don’t run on rails. After filling the streets with protesters for 10 consecutive days, however, the democratic opposition is confident enough of its popular support to form a 35-person “co-ordination council” of artists, writers and business people to oversee the transfer of power.

It could go quite smoothly if Lukashenko accepts that exile is his best remaining option. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, probably the real winner of the election two weeks ago, says she would become president only long enough to organize a new, free and fair election (which her imprisoned husband would probably win).

But win, lose or draw, there are two encouraging conclusions to take away from the Belarusian events. The first is that winning an election is now the only way of achieving political legitimacy almost anywhere in the world. Apart from China, a few other Communist countries, and a few Arab countries, all countries now require popular consent expressed in a public vote.

Many of those votes are rigged, of course: winning elections is easy if you control the media, the police and the courts. But the principle is now almost universal: it’s now as important to win some sort of election, however flawed, as it was 300 years ago to prove you were the true and legitimate heir to the throne.

Lukashenko won five such elections over 26 years before coming a cropper this time: the point is that the requirement to win an election creates repeated opportunities for non-violent protest to flourish, and often even to triumph. For all the abuses and disappointments, it has made the world a better place.

The second cheering thought is that state-sponsored violence is less effective than it used to be: Lukashenko tried it for two nights, and then backed away from it. The problem is that violence is always ugly, and social media technology has made it much more visible. This might deter some people from activism, but it seems to motivate more people to protest.

The same consideration applies to military force deployed across borders to decide political outcomes elsewhere. This is something the old Soviet Union used to do with complete impunity — East Germany 1953, Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968 — and as late as 1981, the mere threat of it forced the local Communist regime to impose martial law in Poland.

On one occasion, the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the current regime in Russia has done the same thing, but that only worked because most of the local population was Russian and wanted to be annexed.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin certainly doesn’t want to see Lukashenko overthrown by a non-violent democratic uprising in Belarus — the parallels with his own situation in Russia are alarmingly close — but he probably doesn’t dare to send in Russian troops even if Lukashenko asks for them. To do so could be the trigger for a similar popular movement in Russia.

We are still a very long way from the Promised Land, but the balance of forces has changed, perhaps permanently. It is the dictatorships, not the democratic governments, that must worry constantly about being overthrown, and from Putin in Russia to Sisi in Egypt to Mnangagwa in Zimbabwe to Chan-ocha in Thailand, they are very worried indeed.

So we should encourage them all to steal enough money that they can go into exile with an easy mind when their time finally comes. (They must know it may come one day; why else would they bother stealing so much?) And this is where the real problem with Lukashenko could arise: he may not have been corrupt enough.

Gwynne Dyer’s latest book is Growing Pains: The Future of Democracy (and Work).