Do attack ads really work?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/06/2019 (2363 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

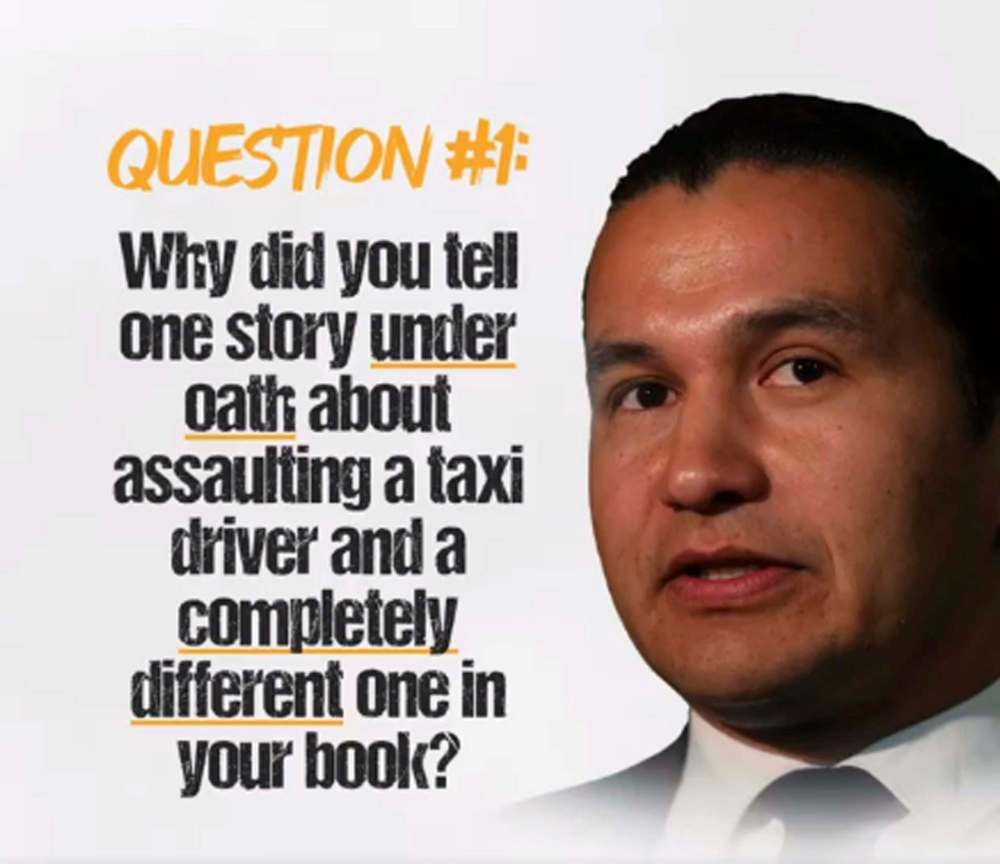

Manitobans hoping for a pleasant provincial election campaign that would start later this summer, after the writ is officially dropped, and continue past Labour Day in the lead-up to the Sept. 10 vote, were likely disappointed when the pre-campaign “campaign” in fact started with a bang: the appearance last week of a new Tory attack ad against NDP Leader Wab Kinew, which focused attention on Kinew’s 2004 drunken assault of a taxi driver.

The attack ad appeared on the PCs’ Facebook page, and emphasized inconsistencies between Kinew’s description of the attack at the time and, later on, in his book. Besides reviving an embarrassing episode for Kinew, the ad appears to the first step in building a narrative that Kinew is willing to change the facts to suit his own purposes, and therefore cannot be trusted.

The NDP surely anticipated these attacks. They should expect more, especially if Kinew and the NDP perform well in the coming campaign. If the Tories are smart, they will use these ads to both brand Kinew and build an unflattering narrative around him, not just to embarrass him.

We are likely moving into an aggressive, no-holds-barred election campaign. But this raises the question: when Canadians are often alienated by the cynical tone of politics, why do parties continue to deploy attack ads during election campaigns? The answer is simple: because the people who run political campaigns believe attack ads work.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to support this. In recent history, the federal Conservatives plowed through two successive Liberal leaders by adeptly framing them in a negative light through the use of attack ads. Liberal leader Stéphane Dion was subjected to a barrage of Tory attack ads claiming he was “not a leader.” The ads worked, and Dion went down to defeat.

Encouraged by their success, the Tories did the same to the next Liberal leader, Michael Ignatieff, claiming he was “just visiting” and would depart for his old job as a professor at Harvard University if he did not win the 2011 federal election. The ads found their mark once again, and Ignatieff lost (and in fact, did eventually return to Harvard).

But attacks ads can also be dangerous to those deploying them. In the 1993 federal election campaign, for example, the Conservatives aired an ad portraying Liberal leader Jean Chrétien in a series of unflattering poses while the voices of “regular Canadians” were played wondering about his competence. “I personally would be very embarrassed if he were to become prime minister of Canada,” one voice solemnly said.

Commentators immediately noted that the pictures of Chrétien seemed to be designed to accentuate the facial paralysis he had suffered as a child as a result of Bell’s palsy. Chrétien seized on the “low blow.” “God gave me a physical defect,” he said. “I’ve accepted that since I was a kid. When I was a kid, people were laughing at me. But I accepted that because God gave me other qualities and I’m grateful.”

“It’s true that I speak on one side of my mouth. I’m not a Tory, I don’t speak out of both sides of my mouth.” Chrétien’s response was the death knell for the Tories’ faltering campaigning, and the Liberal leader subsequently became prime minister.

The lesson: attack ads must be handled carefully, even gingerly.

Surprisingly, given their omnipresence in campaigns, political scientists are still not entirely sure whether negative political advertisements work. Negative ads might work in two ways: by persuading voters who were thinking of voting for a candidate’s opponent not to do so after all, or by making voters who were likely to vote for an opponent less likely to vote at all. The hope is that negative ads can either turn voters off a candidate or turn them off voting in general.

But a comprehensive literature review conducted in 2007 found that while negative ads are more memorable than positive ones, their effect on political behaviour is severely limited. People were not persuaded to not vote for a candidate and they were not dissuaded from voting. Other more sophisticated studies followed, and found that advertising effects for voters are generally short-lived.

But it’s not political scientists who make the decision of whether or not to run negative ads. Rather, it’s campaign strategists, and they are often convinced that negative ads can make a big difference. One reason why — and there is evidence to support this view — is that people are more likely to pay attention to negative than to positive advertising. In the same way that we are curious about a hurricane but not a light rain shower, negative advertising seems to get through to voters more effectively than positive reinforcement of parties’ own candidates.

Given this, it makes sense for the NDP to respond in kind by baring their teeth at the Tories. But they should also not ignore the importance of building a reservoir of goodwill for Kinew. There is a chance that the Tories could go too far with their attacks.

Royce Koop is an associate professor and head of the political studies department at the University of Manitoba.