Three centuries of hard times, and counting

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/11/2010 (5515 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

1700s:

Indigenous people migrated into the Island Lake region, according to Victor Harper of Wasagamack, who leads cultural awareness workshops.

1818:

The Hudson’s Bay and the North West companies had established trading posts at the lake by this time.

1891:

Seeing how much better off treaty communities such as Norway House appeared to be, Island Lake Chief John Wood pleaded through an intermediary for a treaty chest from the Canadian government. “The road from Island Lake is very bad…

We are very poor and we cannot help ourselves in any way. We have got no tools to build our houses with… I am letting you know that our place is very rocky.” Sadly, the words are still pretty accurate today.

1903:

The Ottawa Citizen published an article about the Island Lake region headlined: Indians starving. A Methodist church mission was established at the lake the same year.

1909:

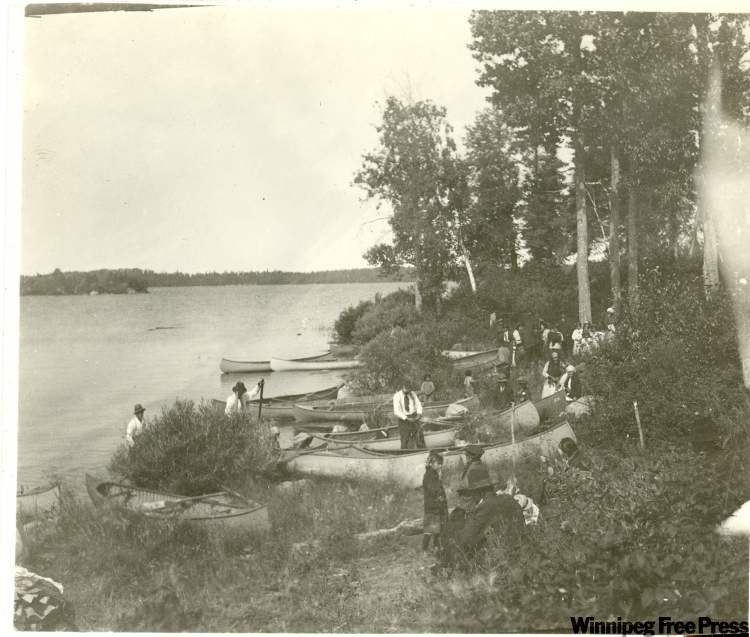

Chief George Nott, Coun. Joseph Linklater and Coun. John Mason signed onto Treaty 5, originally signed at Berens River and Norway House in 1875. About a quarter of the Island Lake people were Cree from the Stevenson Lake-Gods Lake area to the west and north. The rest were Ojibwa, originally from the Deer Lake-Favourable Lake and Sandy Lake-Big Trout Lake areas of northwestern Ontario, according to a linguistic study published in 1973. People in the area ended up speaking a dialect of Ojibwa mixed with Cree words, known as Oji-Cree or Anishininiimowin. The language includes some words borrowed from Plains Cree via a missionary Bible translation. The Cree for water is “ni pi,” according to Harper.

1913:

A government surveyor arrived to establish reserve boundaries.

Early 1920s:

Roman Catholics set up a mission at Maria Portage, now known as St. Theresa Point.

1960s:

A lengthy decline in world fur prices due to ranched fur, artificial fur and foreign competition drove indigenous people across northern Canada into settlements.

1967:

The three communities on Island Lake got low-amp diesel power, not suitable for heating.

1969:

The Island Lake people split into four bands: St. Theresa Point and Wasagamack to the west — largely Roman Catholic — and Garden Hill and Red Sucker Lake to the east — largely Protestant.

1990:

The United Nations charged Canada with a human rights violation for its treatment of the Lubicon Lake Cree, after they formally requested an investigation. Twenty years later, the Alberta community is still struggling to get running water — and resolve a host of other rights issues — Amnesty International points out on its website.

1994:

Manitoba’s chief medical officer, Dr. John Guilfoyle, warned contaminated water on another northern reserve, Mathias Colomb Cree Nation of Pukatawagan, could kill residents, but he didn’t have the power to intervene in federal jurisdiction. Red Sucker Lake Chief Fred Harper pointed out that things were equally desperate in his community, so Indian Affairs Minister Ron Irwin announced a $300,000 grant to study water problems at Red Sucker Lake.

1999:

Island Lake was finally linked to Manitoba Hydro’s electricity transmission grid.

2001:

In the wake of both the Walkteron tragedy in Ontario, where seven people died from drinking bacteria-contaminated water, and a similar outbreak in North Battleford, Sask., consultants assessed water and sewer facilities on First Nations across Canada. Neegan Burnside concluded $556 million in capital upgrades were required on Manitoba First Nations, including $201 million to connect unserviced homes. “The most pressing concern with water supply is found in the delivery system. Approximately 17 per cent of homes in the region do not have service.”

2004:

The first phase of piped water and sewer for St. Theresa Point at a cost of $11 million.

2005:

Manitoba senior Liberal MP Reg Alcock committed $25 million for sewer and water upgrades in Oxford House, Norway House and Shamattawa. Garden Hill Chief David Harper questioned why communities that already had running water were getting upgrades while his people were still hauling water in buckets and using outhouses. Meanwhile, the federal auditor general pointed out that Indian and Northern Affairs Canada considered it unacceptable that some communities had little running water, without having a plan for how to address that problem within available funding.

2006:

Residents of Island Lake remain among the most culturally traditional indigenous people in North America, as evidenced by their continuing use of the Oji-Cree language. The census showed 88 per cent still spoke at home the language also spoken in parts of northern Ontario. Some Island Lake community leaders wonder whether the values of respect, patience and hospitality still practised by traditional families make the community less likely to raise a ruckus when governments turn down requests for help. “We just don’t make enough noise,” said former Garden Hill chief Darcy Wood.

September 2006:

The Northwestern Health Unit based in Kenora embarrassed the federal government by distributing a report on Pikangikum, Ont., which also lacks running water. It concluded: “It is probable that many residents of the community have suffered illnesses as a result of these dysfunctional and unregulated water and sewage systems.”

November 2006:

The report of the Expert Panel on Safe Drinking Water for First Nations chaired by Harry Swain urged “rapid action” to deal with communities without running water, which are not even on the government’s list of “high-risk” systems.

2007:

The first phase of piped water and sewer for Garden Hill and Wasagamack, costing $36 million.

May 2009:

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada awarded Neegan Burnside an 18-month contract to assess water and waste-water systems on First Nations across Canada to “help ensure money is going where it is needed most.” The work is handled out of the consultant’s Winnipeg office.

May 2010:

The federal Conservative government introduced a new Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act. Dalhousie law professor Constance MacIntosh says communities such as Garden Hill without piped-in water are “orphaned” by the legislation, which ignores the health risks of their unusual situation.