Source of light in the darkness

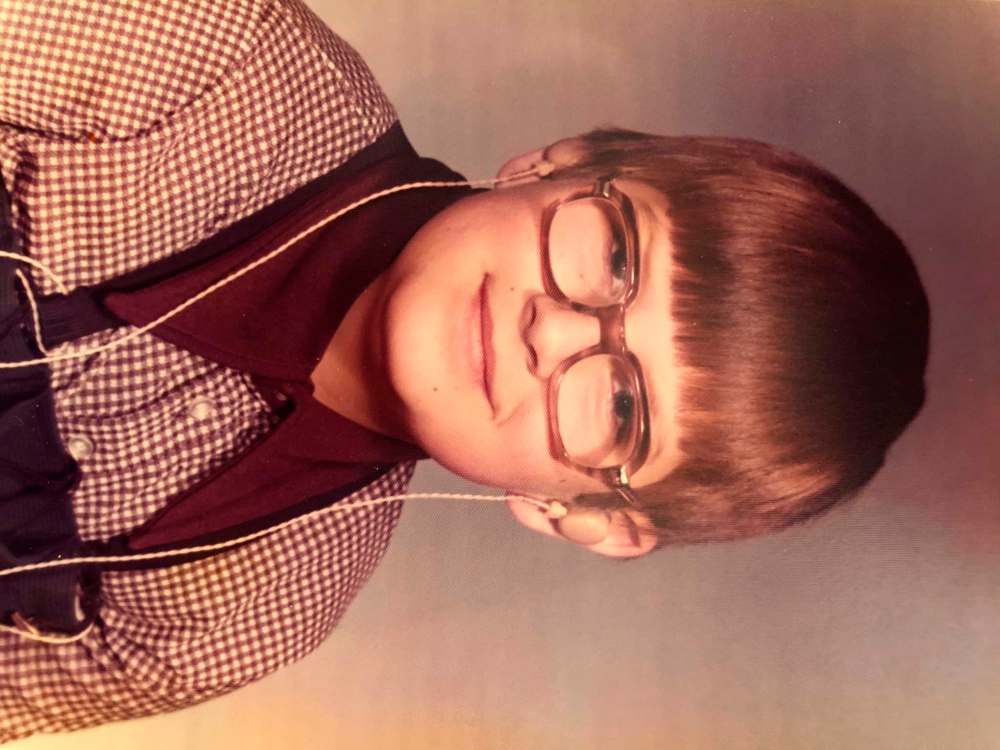

Ambassador for deaf-blind, Neil Hobson, 54, embraced world

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/11/2019 (2303 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Neil Hobson stood on the mound at Shaw Park two summers ago, cradling a baseball in his hands as he got ready to throw the ceremonial first pitch before a Winnipeg Goldeyes game.

He loved watching sports. And here he was, standing at the centre of the ballpark, with the whole crowd watching him for a change.

Understandably, he was nervous: he’d gone to the park a few days earlier to practise. He wanted to throw a respectable pitch: how often does a fan get a shot at being a star?

For Hobson, who died of complications of diabetes in July at the age of 54, the pitch meant something: it was a moment to dispel other people’s doubts; to show he had defined his own path; to show even a man who couldn’t see or hear could still feel, could still accomplish, could still be.

When Hobson was born in Brandon in 1964, once his eyes had adjusted to the light of the outside world, his face would brighten as soon as he saw his mother or father. He was beautiful, his mother, Edith, recalls.

A few months later, she and her husband, Walter, realized Hobson was not responding to the world around him quite as expected.

They took him to a doctor. Hobson could see fine, but something was wrong with his ears. The doctor likened it to a radio station being set between channels, the sound muffled beyond recognition: he was deaf.

In the mid-1960s, the diagnosis was a terrifying one: societal norms often dictated that a child who couldn’t hear couldn’t act like a “regular” kid. They were destined to be relegated to a separate world — passive participants in towns and cities simply not built for them.

“Don’t get home and put him in a closet,” the doctor told the new parents, a harsh indication of the times.

The Hobsons took that advice to heart. Edith and Walter got down on the ground to communicate directly with their son. They taught him through repetition, and his intellect was immediately apparent.

After moving to Winnipeg, Hobson became a part of the first class of deaf children in Manitoba to learn how to verbally talk in a formal setting, attending pre-school classes two times a week for three hours each time. He went on to Mulvey School, with a cohort of non-hearing and hard-of-hearing children who then went to Gordon Bell and Tec Voc schools together. He wore hearing aids in each ear, costing $500 each, with cords dangling down around his neck.

“He was a typical little boy,” Edith said.

As typical little boys do, he played hockey in the street, he rode a skateboard and a bike, he played soccer, he watched movies, he loved the Montreal Canadiens, he listened to music — feeling the vibrations and sensing the sound as it blared through the stereo. He discovered the world, and he loved it.

At Tec Voc, Hobson found himself in the dental technician trade course. His attention to detail and patience made him an ideal tech, and upon graduation, he secured a full-time job in a local lab.

“He had a mature outlook in high school,” said Janet Bock, who taught Hobson for six years, and remained a lifelong friend. “These kids had the same hopes and dreams every kid had. They wanted to be successful, and they wanted to get jobs and become independent.”

For 20 years, Hobson worked in labs, building his skills and growing as a person. He would go to Winnipeg Jets games (before the NHL team left for Arizona), watch the Goldeyes play, read the newspaper front-to-back each morning.

But when he turned 40, Hobson had a jarring experience. His vision started to dissipate, and despite six surgeries, nothing could be done to save it.

Hobson became what’s known as deaf-blind. The Canadian Deaf-Blind Association estimates about one in 3,000 Canadians is deaf-blind; in Manitoba, the Resource Centre for Manitobans who are Deaf-Blind, said there are fewer than 100.

Deaf-blindness, though rare, is not equivalent to a life sentence of misery or inability, said Bonnie Heath, executive director of ECCOE (a Manitoban interpreting and intervening services). It is challenging, but people who are deaf-blind, like any people with physical or mental impairment, are still people first, and still have hobbies, talents, hopes and dreams.

Hobson was frustrated to lose his vision, but soon moved into the resource centre full-time, and learned to communicate using hand-over-hand tactile American Sign Language, in which an intervenor taps on the deaf-blind person’s hand to represent certain letters.

Scotty Duré, one of Hobson’s longest-tenured intervenors, said their conversations were wide-ranging: they talked about everything from the Jets to the world around them.

Duré saw a video online of a deaf-blind person in Brazil watching a hockey game, using a table-top rink and the intervenor’s guidance to show what was happening. Hobson would like that, Duré thought, and soon, they went to watch a Jets game together, with the team giving him a pre-game skate. (Hobson wore his Montreal jersey under his Jets one.)

Hobson refused to let his condition limit him. At the first deaf-blind camp at Camp Manitou last summer, he went ziplining. He became an ambassador for the deaf-blind, and helped the local organization learn more about the condition with his tremendous communication skills. His insight will shape how the deaf-blind are treated in the future, said Angela Mayen-Obregon, the resource centre’s co-ordinator.

“The only thing that could limit Neil was (the general population’s) misconceptions and misunderstandings,” said Duré. “He could do it all.”

So when he stood on the mound, with Mayen-Obregon behind him to turn him toward the plate, Hobson was pitching for more than his own satisfaction. He was pitching to show even though he didn’t have a sense of sight or a sense of hearing, he still had a sense of where he was, a sense of the world around him.

He wound up, and threw the ball straight ahead. He knew he could do it.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @benjwaldman

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.