She conquered, quietly

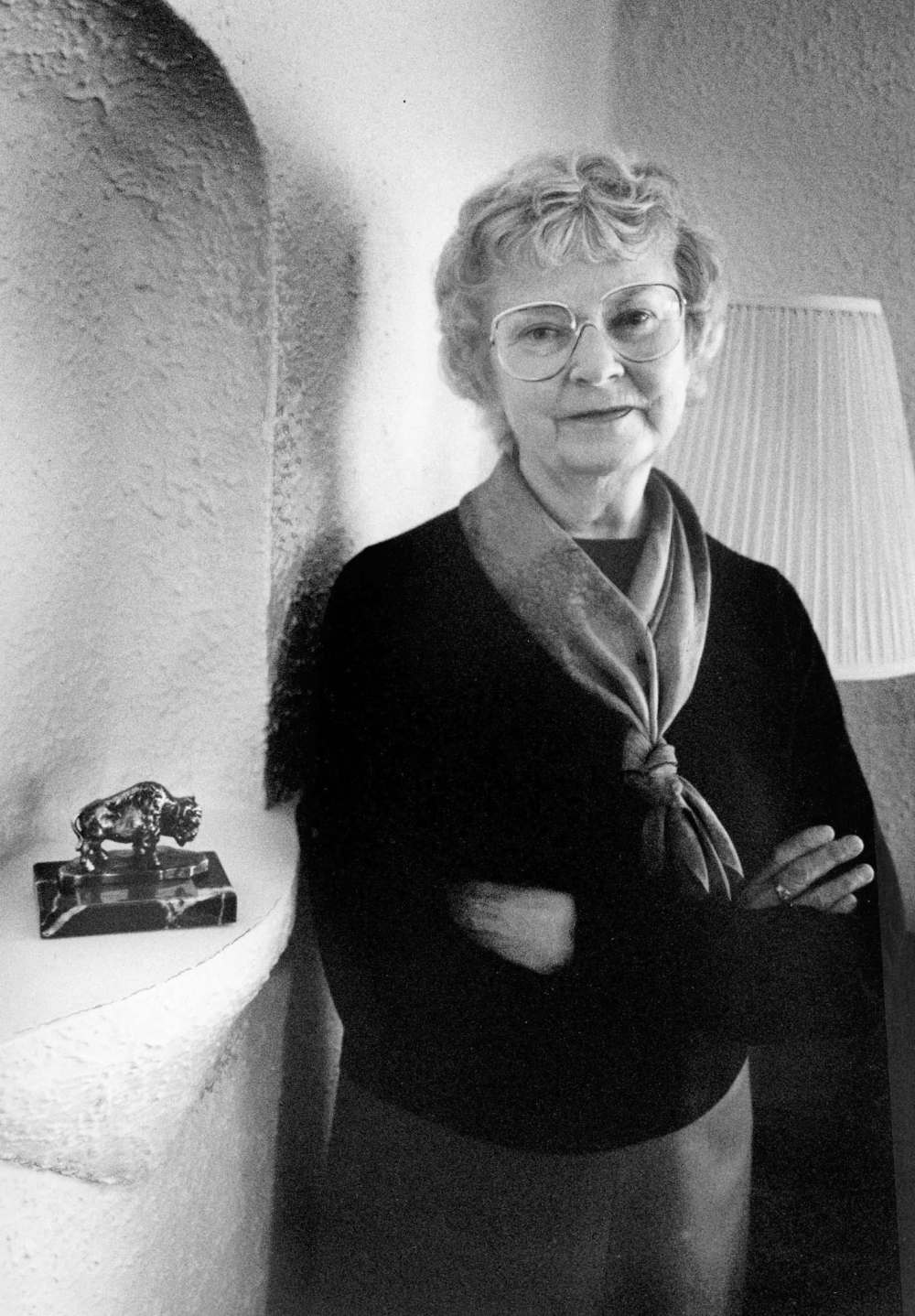

Fearless, ferocious women's rights advocate Berenice Sisler 'one of the greatest Canadian feminists of the 20th century'

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/06/2019 (2457 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Ask Berenice Sisler’s family and friends to describe her, and they find many of the same words. She was “tenacious,” they all say, and “feisty,” and bright. She was funny, with a dry humour that cut through all the political noise. She had a finely tuned sense of what was just, what was ethical, what was right.

They also say this: despite all of her work, and all the accolades she earned, Sisler never saw herself as a leader.

Yet a leader she was, in her own unflappable way, and when she died on April 5, she left a legacy of advocacy that helped secure many of the rights women in Canada hold today. For that, Quebec lawyer Louise Dulude wrote in an email, Sisler “deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest Canadian feminists of the 20th century.”

The roots of that work began in 1924, when Sisler was born in Winnipeg. Her father worked for the telephone system, and often engaged his children in long intellectual discussions; her mother, a Norwegian immigrant from a humble background, was active in church with a deep interest in community work.

Like her father, Sisler sought knowledge; like her mother, she looked for ways to help. She was a bright student at East Kildonan Collegiate, and went on to earn an education diploma from the University of Manitoba. She delayed her marriage to George Sisler for a year so she could teach school in Dauphin.

Once married, the couple moved to Kentucky, where George completed his psychiatry residency. He was offered a job there but the couple, disturbed by the hospital’s racial segregation, declined to stay. They returned to Winnipeg, where George built his practice and they set about raising two children, daughter Lesley and son John.

At home, Sisler was a consummate hostess and homemaker. She was a talented baker, Lesley Sisler recalls, and had a deft touch with knitting needles. She channelled her creative flair into many pursuits: she made hats, pressed flowers and sewed elaborate outfits for the children’s special events.

From the start, Sisler understood these domestic efforts as labour, albeit unpaid and often under-recognized by society. She also bristled at the strictures the era placed upon women: her daughter once overheard her verbal sparring with a 1960s airline agent, who insisted she must book a ticket as “Mrs. George Sisler.”

She found an outlet for that surging feminist spirit through her volunteer work with the YWCA. She would be involved with the organization for more than 30 years, including a stint on its national board; that work became her entry into political organizing and public women’s rights advocacy.

She arrived at a critical moment. In the 1970s, the circle of social advocates in Manitoba was small. Bev Suek, who first met Sisler around that time, recalls how a certain group of women took to calling themselves “the same damn bunch,” due to how often they would find themselves working together on key causes.

One issue, in particular, drew Sisler’s attention. At the time, family law in Manitoba was deeply unfair for women, riddled with sexist provisions; women were frequently shut out of a fair share of marital assets after divorce, and judges often made discriminatory rulings against them.

Fixing that injustice became Sisler’s passion. Together with a coalition of similarly determined women, she threw herself into the work of building change. She spent hours at court, studying rulings and staring down lawyers who challenged her presence; she wrote incisive briefs, organized meetings and lobbied the province.

In 1995, Sisler documented that movement in a book, A Partnership of Equals. Written in longhand at her kitchen table, it stands as a seminal and meticulously detailed account of the fight for equality in Manitoba. Above all, the book — available at Winnipeg libraries — pays deep respect to all the women who helped raise the tide of change.

That respect ran both ways. Her peers revelled in her disposition, which was perfectly suited for feminist advocacy. Besides her intellect and drive, she was also unyielding when it came to what she believed, and unafraid of how she would be perceived. Stories of her chutzpah abound.

Once, as a board member for a non-profit women’s employment counselling centre, she walked out of a meeting with a condescending provincial bureaucrat to whom the board had turned for funding.

“Berenice stood up and said, ‘We’re not taking this. We’re leaving,’” Suek remembers. “We all just followed Berenice out of the room.”

The bureaucrat, Suek recalls, was shocked. Those who knew Sisler were not. The counselling centre ended up getting its funding anyway, and the anecdote would serve to illustrate something of Sisler’s fearless spirit: she suffered neither fools nor poor treatment gladly, and did not wither in the face of power.

Yet behind that steely resolve was a sensitivity that her friends came to cherish.

Sisler was caring, longtime friend Betty Hopkins recalls, and always quick to support her peers’ many projects. She had a “fire in her,” Hopkins says, and it just as often burned with gentle warmth, as well as heat enough to change the world.

“I really felt that she was always authentic and genuine,” Hopkins says. “Honesty and justice mattered to her, and she had a passion for them, and they influenced all areas of her life…. She was angry, and she said she was angry, but she also had a soft, caring side. She was a good friend.”

And a busy one. Many pages could be devoted to Sisler’s community work, from serving on Assiniboine Park’s resident advisory group, to the federal Charter of Rights Coalition. In 1980, she was named to the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women, and wrote a key presentation on pension reform.

For these efforts and others, she was lauded. In 1985, Sisler was bestowed with one of Manitoba’s most prestigious honours, the Order of the Buffalo Hunt; the next year, she was feted nationally by the governor general. Later, she received an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Winnipeg.

She never sought the limelight. In fact, she sometimes declined it, suggesting others be recognized instead.

In her eulogy, Lesley Sisler noted how, on her resumé, her mother summarized her activities from 1952 onward with a simple seven-word description: “Home manager, volunteer, activist in women’s movement.”

That is how Sisler saw herself. To historians, she will be seen as a crucial advocate who helped make Canada a better place for women. To those who knew her, she will always be Berenice — a brilliant and relentlessly determined woman who stood up, spoke out and had some fun along the way.

At a time when relatively few women held positions of power, her voice mattered.

“I don’t think a lot of people nowadays realize how different it was then, and how things have changed so much,” Suek says.

“Berenice was someone who took the lead on things. I learned a lot from her… never accept things that are not right or not ethical. I’ve really lived that in the way that Berenice lived that.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.