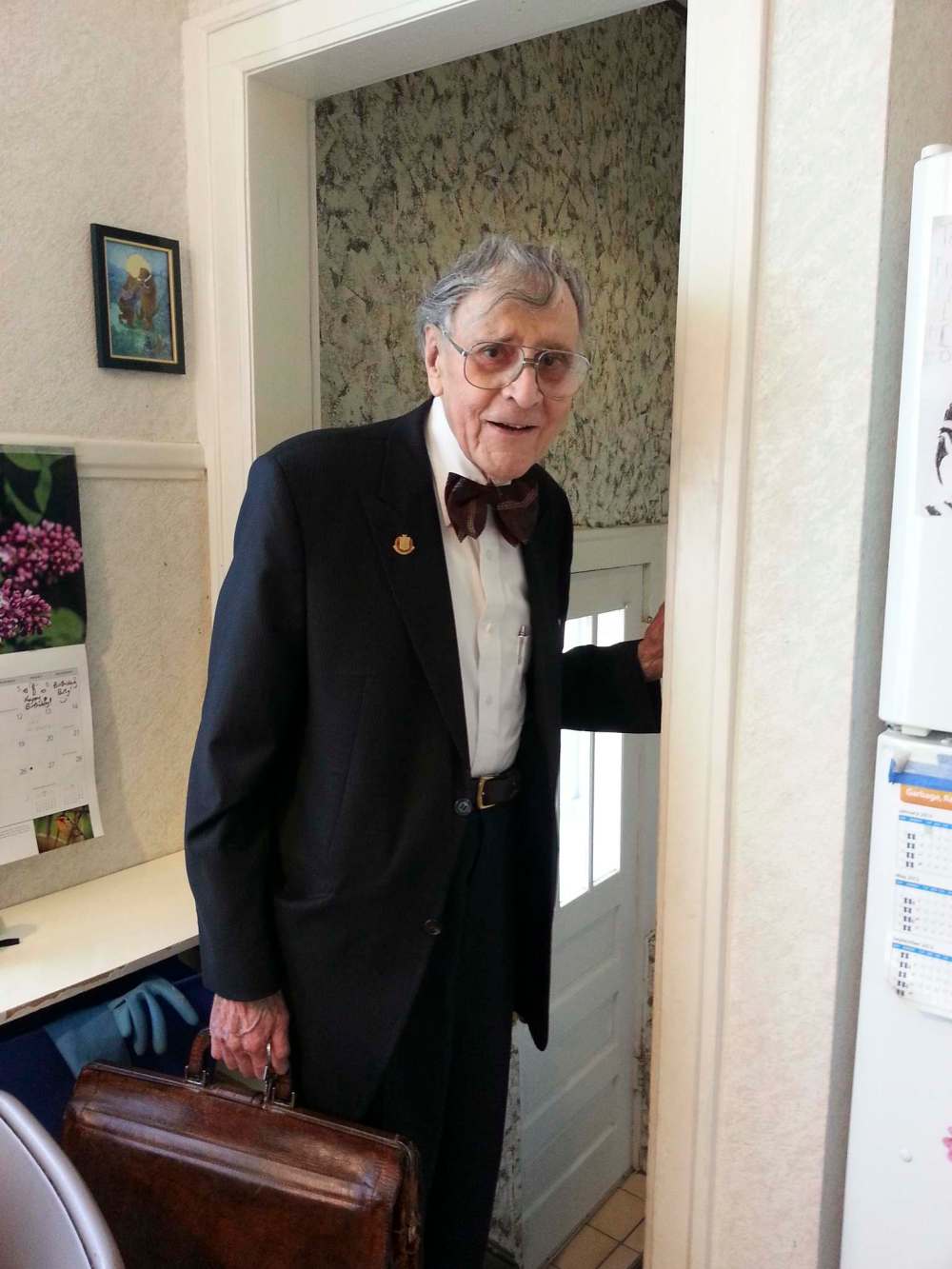

Pioneer MD a role model

Meticulous diet, passion for invention and patient safety led Lloyd Bartlett on near-70-year medical career

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/06/2019 (2464 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

At 101, Dr. Lloyd Bartlett was still doing push-ups, lifting small weights, and living independently, fuelled by a carefully designed plant-based diet he’d been following long before it was in vogue.

He died earlier this year at Grace Hospital, where he had worked for about 50 years.

The Winnipeg surgeon had stayed current on the latest medical research, daily news and nutritional advances and shared his secrets for lifelong wellness with longtime patients.

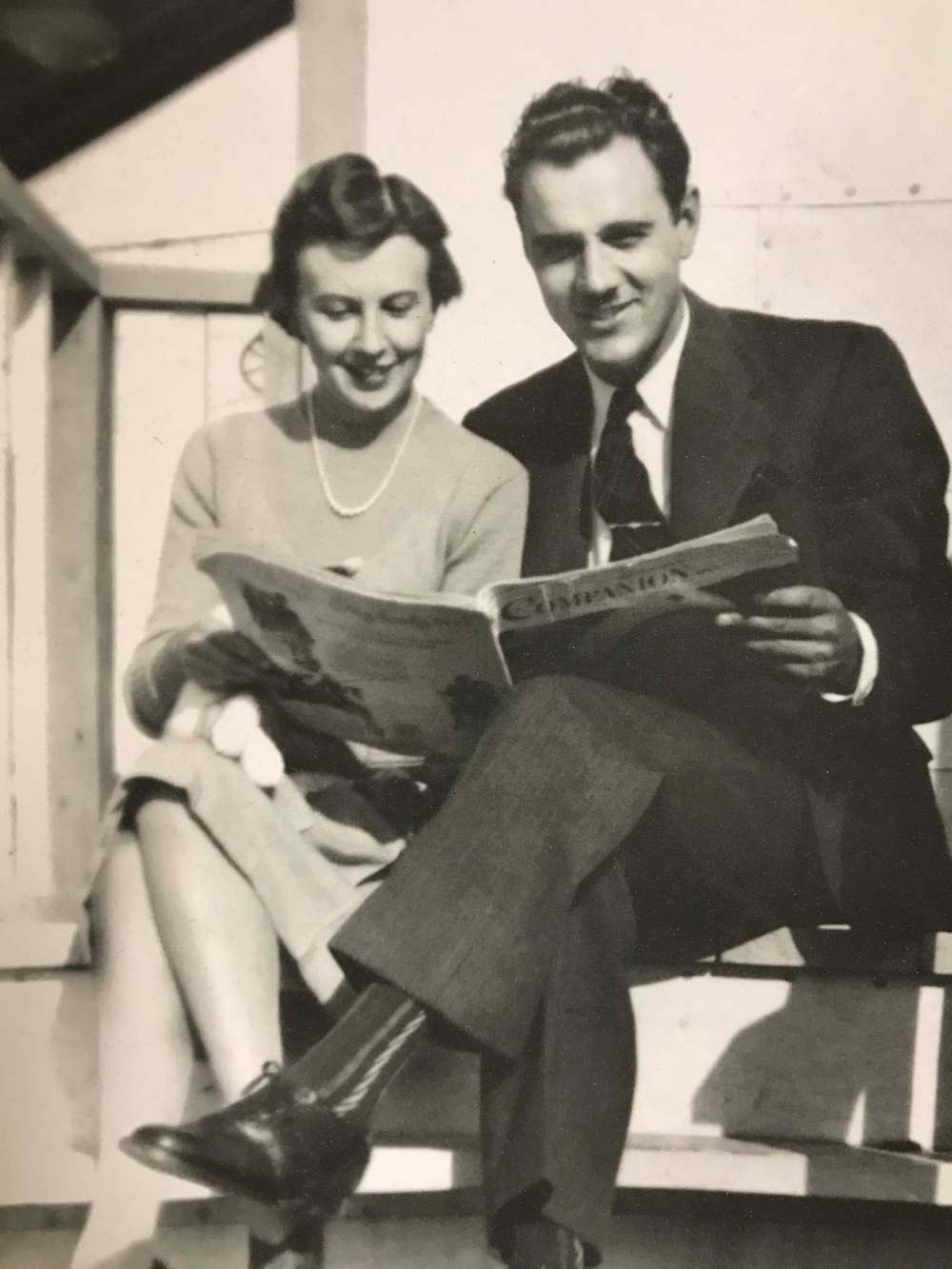

For those who knew him, it wasn’t hard to see what kept him going: he worked alongside the love of his life for nearly 70 years, diagnosing Winnipeggers’ ailments to help them live longer.

“He was always on the cusp of something new. His latest interest in terms of diet was something called glycation, which is probably going to be as familiar to everybody in five or 10 years as cholesterol is now,” said Lorna Kopelow, one of Bartlett’s five children.

It was the last in a long line of research topics he was passionate about before they became popular.

As an early adopter of anti-tobacco information, Bartlett created pamphlets to encourage patients to quit smoking, and lobbied for non-smoking legislation on behalf of the Canadian Medical Association.

As early as the 1970s, he was part of a committee that studied how seatbelts prevent traffic deaths. In 1983, he spoke to Manitoba’s legislative assembly, urging politicians to bring in stronger laws on seatbelts and helmet use.

In 1996, Bartlett received a national award for his anti-smoking advocacy. Facts about the benefits of exercise and proper nutrition filled additional pamphlets he would design and distribute to patients.

Arline Christopherson, 85, was Bartlett’s patient for more than 50 years. Over time, they and their families became friends. His thoroughness and willingness to treat patients on short notice was a calling card, she said.

“I always felt I was in good hands with him. And something that really struck me was, his wife died about two days before my husband, and he phoned me the day that my husband died to see how I was doing,” Christopherson recalled. “I thought that was really something.”

Bartlett retired just nine months before he died, capping off his nearly 70-year career as a general practitioner — a practice he started with his wife, Desta, a pediatric nurse. Desta worked alongside her husband until she was 95. She died two years ago, at 99.

“I think (there was) a level of personal connection, as well as medical care, when you have people who are there for you for such a long period of time,” said the couple’s second-eldest daughter, Sheila Bogoch.

“People who are my age would be delivered by my dad and still saw him in their mid-life, so it was an important piece for both of them, the medical practice.”

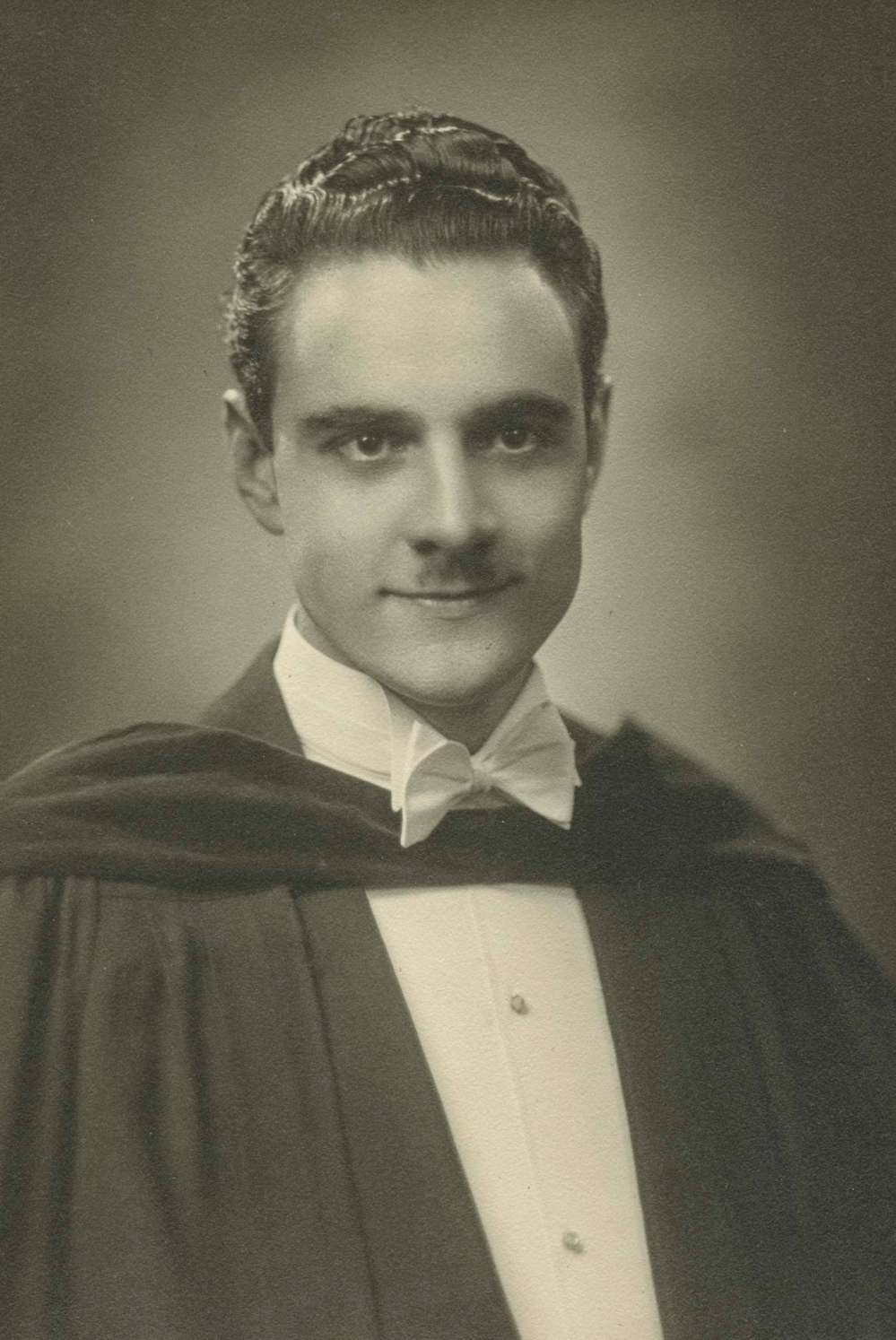

The family remembers the couple as hardwired to be hardworking. Bartlett left his hometown of Stratford, Ont., to put himself through medical school at the University of Western Ontario. He paid his way by working for room and board in a tuberculosis sanitarium, and by growing cucumbers to sell to a local pickle factory.

“He used to tell us how he couldn’t afford tires for his bicycle to get the cucumbers to the pickle factory, so he made tires out of rope,” Bogoch said. “All those (Great) Depression stories.”

He met Desta in Ottawa. They married in the early 1940s, and moved to an isolated mining town in northern Ontario called Favourable Lake.

There, Bartlett made house calls, picked up dentistry skills, and learned some optometry.

He found ways to be creative, especially during those times of year when winter roads weren’t in service.

“I think in the north they really were challenged, and I think my dad was delighted that you had to figure things out on your own, and it really prompted him to just look at a problem, try to analyze it and find a doable solution. That was a joy in his life, there was nothing he liked better than tackling that kind of problem,” Bogoch said.

Bartlett’s creativity shone via his inventions, from designing a rhubarb cutter for his mother when he was young to creating what was believed to be the first cannulated needle used for intravenous procedures.

His ideas for new technologies reflected the range of his medical education — “He was a real generalist,” Bogoch said.

He developed devices to improve feeding tubes and gastric suction, and created a surgical technique to cure pancreatic fistulas.

“Inventiveness was one of the main things that you’d notice about him… He loved creating things, and I think he got that from his dad, who was an inventor,” Kopelow said.

After they moved to Winnipeg in 1950, Desta did the “lioness’s share” of the work at home, Bogoch said.

She got creative in the kitchen to accommodate her husband’s evolving plans for his diet. He was strict about what he ate — “religious” about nutrition and fitness — but didn’t force his lifestyle on anyone else, his two eldest daughters said.

“He wasn’t domineering about it in any way. He would give information, but then let it be, recognize people’s intelligence and their freedom to choose,” Kopelow said.

Although he ate mostly vegetarian and eventually cut out dairy, the sharp, spreadable cheddar of Imperial cheese and smooth, creamy (albeit low-fat) ice cream were his guilty pleasures. They were squeezed out of his usual meal plan.

“For the last decade or so of his life, he ate an exact meal that he designed. The same thing every day, like 10 different kinds of vegetables, a piece of salmon, blueberries — and it worked for him,” Bogoch said.

At work, in the office he and Desta shared, Bartlett designed the floor plan so patients could move in and out in the most logical way. He got a grandson (one of nine grandchildren and six great-grandchildren) to help him with sound engineering so anything said in the exam room couldn’t be overheard in other areas of the office.

“He liked to finesse things till they worked really well. He really liked things that ran smoothly,” Kopelow said.

Bartlett never stopped being interested in life — likely one of the keys to his longevity, Bogoch said.

“Sometimes, you meet older people whose life has shrunken in so much and, sometimes, that’s fine if you’re a contemplative person, but it was nice to know somebody that age who still really cared about the world.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.