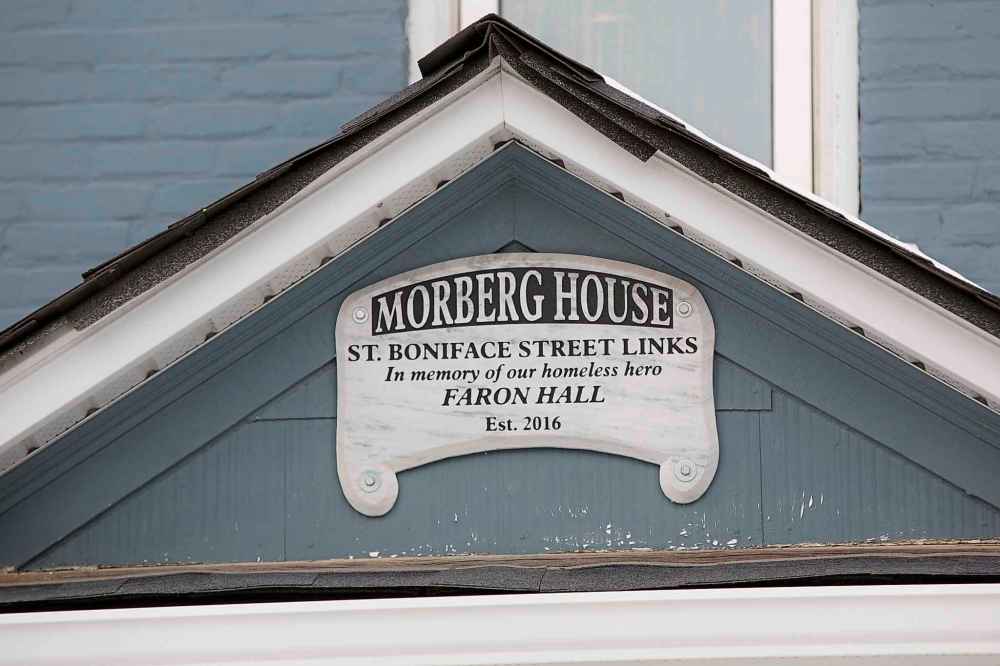

Crawling out of the dark A former convent in St. Boniface has quickly become an oasis for meth addicts who want their lives back; the force of nature running Morberg House and her staff just 'find a way'

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/12/2018 (2550 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Under a beam of morning sun, Ricky Aitken is bent over a table, jotting long lines on a sheet of paper. Lyrics, he explains. He wants to be a rapper. He’s seen hip-hop artists from Winnipeg succeed, and that is also his dream.

At 31, Aitken has the space to dream again, that’s the main thing. He has a new foundation, a reassuring solidity under his feet. He knows where he stands now. For years, crystal meth had knocked him down.

He’d used it before, as a teen, though he didn’t like it much then. But in December 2015, he met a woman who used meth, and started doing it with her. It started out as a “sex drug,” he says, but before long, it wasn’t just that anymore.

From there, Aitken’s life spun out of control, a path familiar to many heavy users. Once an athletic six-foot-one basketball player at Dakota Collegiate, muscle began to melt off his bones. He wasted away, falling deeper into meth’s world.

Walking down the street, he heard an endless chorus of offers: “want some ish?” someone would ask, using a slang term for meth that experts say seems to be unique to Manitoba. He shudders now, as he repeats the familiar words.

The terror common to heavy meth users gnawed at him. The crashes got worse. Once, near the end of a long binge, he found himself dashing down the middle of Pembina Highway, trying to escape the shadowy figures close behind.

Another time, he had a hallucination that his family was being kidnapped. Something told him the only way to save them was to smash a cinder block on his leg. He did it right there on the street, to the horror of a cyclist passing by.

Aitken saw things in those months that he still struggles to speak about. Things that left him traumatized.

And yet he could not quit the drug. He tried many times, falling into and out of detox. He slept on friends’ couches. When he was on a binge, he’d roam for hours, once marching a full 13 kilometres from St. Boniface to the Grace Hospital.

“Just like it was nothing,” he says. “And then walking back.”

This is not a story about the depths of addiction, though. It is a story about hope. Because somewhere in that darkness, in the wreckage that meth had made from Aitken’s life, a hospital social worker tossed him a lifeline.

A place called Morberg House. A place where he could live and try to stay clean. He got a bed there July 16.

Aitken was nervous at first; he didn’t know what to expect. But soon after he moved in, taking up a bed in a sprawling old Provencher Boulevard house, he felt the protective walls he’d built around himself start to come down.

“I’ve got a family now,” he thought as he settled in. “I’ve got a brotherhood.”

It felt good then, he says. It feels good now. It feels like the healthiest thing in the world.

● ● ●

Over the last week, the Free Press has explored the story of meth in Manitoba: the damage it wreaks on city streets; the way it strains front-line resources; the people caught in its grip, trying to break free.

Now, at the end, the story takes a sharp turn as it begins to climb out of the darkness towards lights glimmering in the distance. It follows a map left by those who have gone before, leading the way to recovery.

It’s easy to feel helpless in the face of a surging epidemic. But those lights grow brighter each day.

The hope is hard-won. Crystal meth, experts say, can be a notoriously difficult addiction to treat. There is no medication that helps curb the cravings, nothing equivalent to methadone treatment to ease out of opioid addiction.

Meth is a powerful drug. It overwhelms the mind. It floods the brain with dopamine at nearly 1,100 per cent of its baseline levels, nearly four times the effect of cocaine. In time, that inhibits the brain’s ability to produce its own.

Brain function scans show it can take up to two years for recovering users’ to regain normal dopamine levels.

In the meantime, they may go through months where they are unable to feel pleasure, drifting through life in an oppressive grey fog. Nothing matters. Nothing feels good. For months, a healing meth user will feel no joy at all.

“People don’t recover from meth addiction without some sort of support,” says Addictions Foundation of Manitoba lead educator Sheri Fandrey. “Other addictions they might be able to do it, but I don’t think it’s possible with meth.

“You need somebody in your corner, some positive influence. When it takes 12, 15, 18 months before you start to feel pleasure normally again, that’s asking a lot… when they know their symptoms will go away if they start using again.”

And they must also come face-to-face with their trauma while slogging through the fog of recovery.

That is the root of most addictions, many researchers believe. It is pain, radiating from all the places where communities are broken: poverty, for instance. Or family violence, social dislocation, the child-welfare system.

“Addiction isn’t the issue,” says Mike Millard, a recovered addict who now helps others via the Crystal Meth Anonymous support group. “Addiction is the solution the person has come up with to solve the trauma they’ve experienced.”

And there is the violence that swirls around crystal meth, along with abuse and sexual exploitation. If users aren’t already wrestling with trauma when they first turn to the drug, they almost always are by the time they try to quit.

That trauma can fester, fermenting into feelings of shame. In time, the drug becomes the one thing making life bearable for heavy users, even when it is also what is tearing their lives apart. So how can they learn to stop?

“We don’t have an addiction problem in Manitoba,” Millard says. “We have a living problem in Manitoba. And it goes much, much deeper than $10 for a point of crystal meth and that mega-cheap high. It’s the ‘why’ people are using.”

All of these factors conspire to make meth a difficult addiction to overcome. It’s even harder when poverty and social marginalization keep users trapped in toxic environments, surrounded by unhealthy people, teetering on the edge.

In 2012, Australian researchers found that nearly half the users who went through residential rehab were still clean after three months. But the success rate plummeted quickly: three years later, only 12 per cent of users abstained.

Going only to a short-term detox, meanwhile, showed no effect at all in helping people stay off the drug.

Regular meth users in Manitoba describe the same vicious cycle. They shuttle from the street to detox, then to 28-day treatment facilities, before being released to their usual haunts, where they quickly relapse.

This cycle can confound experts. Dr. James Bolton, medical director for the 24-hour Crisis Response Centre on Bannatyne Avenue, characterizes meth’s challenges as being “uncharted waters” for local health-care providers.

“We need evidence-based strategies to guide us, and there are many evidence-based strategies in addictions,” he says. “But meth is something that’s really pushed our limits about how we understand this drug and what it’s doing to people.”

To survive crystal meth — as individuals and communities — it will take more than just funding, or government reports, or changes to our addiction-support systems.

It will take a village. But that’s the good news: it means everyone has a little bit of power to help get us through.

•••

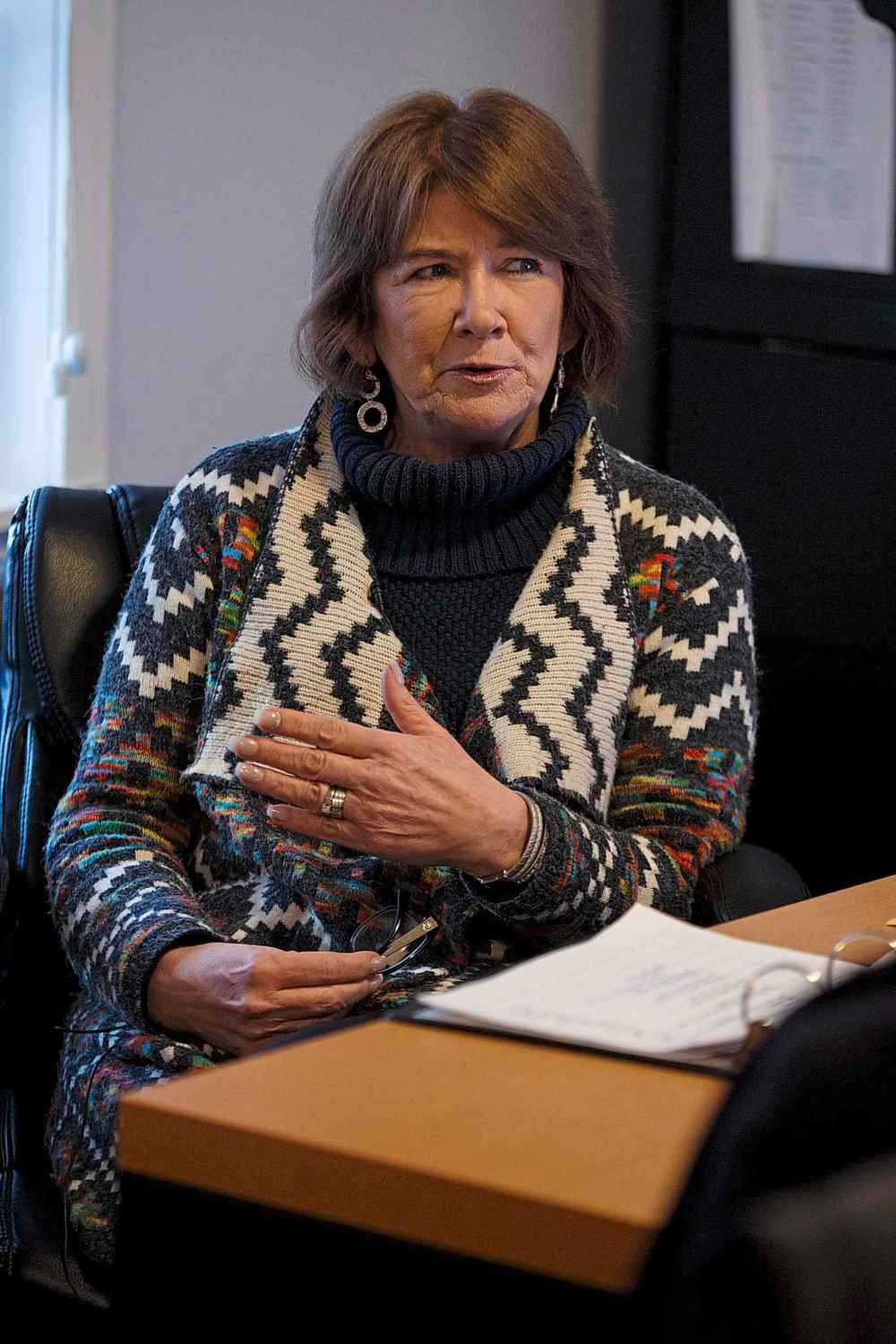

“Most people do well once they get to a treatment centre,” Marion Willis announces. “It’s not really long enough to really dig deep into the underlying root cause of your addiction, or to really identify any mental-health challenges.

“But it is long enough to basically have that period of coming down, and to learn a little bit about yourself. Learn a little bit about addiction. Maybe learn some coping skills so that when you come out, you can make better choices.”

Or at least, Willis adds, that’s the hope. That’s the idea. The problem is what actually happens after folks leave.

“You’re right back in the environment that fed everything for you,” she says. “Relapse is almost a guarantee, and I don’t think anybody who works in a treatment centre would disagree with me. They’ve always had revolving doors.

“That suggests to me that maybe that’s not the best model. And I can tell you, it’s not the best model to address the meth crisis.”

Willis is holding court over Morberg House’s living room from behind her stout, paper-strewn desk on this Tuesday morning. House staffers and residents amble through on their way from one meeting to the next.

Sun streams in through the rambling old house’s large south-facing window. Willow, the resident Labrador puppy, scampers around a trio of visiting reporters, chewing an old shoe, claws clattering a ruckus on the hardwood floor.

The room feels friendly and warm. A tinsel-strewn Christmas tree glitters in the corner. Above the stairs leading to Morberg House’s second-floor bedrooms there is a jewel-toned mural painted by renowned artist Leonard Bighetty.

He’s in palliative care now, with cancer. Before that, he was an artist who struggled with homelessness and often crossed paths with Willis. He lived at Morberg House for a while; they set him up in an art studio on the third floor.

“He created a huge body of work from there,” Willis says softly. “It’s a wonderful gift to this house.”

Willis is both the executive director of Morberg House and, in a way, its spiritual keystone. She’s a natural raconteur, effortlessly loquacious and possessed of a certain dramatic flair; she occasionally refers to herself in the third person.

“If you took Marion Willis out of this, could it still survive?” she muses. “I think so, yeah. Who’s indispensable in life? Nobody. You just have to find the right kind of people to do this. What am I here? Just somebody here who’s older.”

Yet there is more to it than that. Willis is unflappable, nothing seems to shock her. Morberg House residents, sensing that, come to trust her; Aitken describes Willis as “the mother (he) never had.” It gives his recovery a familial structure.

“When I let her down, it’s like, ‘I’m such a piece of s–t,’” he says. “But when I do good, I feel so good inside.”

Aitken is one of eight men living here now, though with renovations complete, bringing the building up to code, Willis hopes to increase the occupancy to 12. And the number could rise again when the basement is refinished.

The residents here are diverse, in all ways except one. They range in age from 21 to 67. One was once a successful white-collar professional before he lost everything to his addiction. Others have lived much of their lives on the street.

But all of them wrestle with addiction. For most, it’s crystal meth.

It wasn’t always like that. When Morberg House opened in August 2016, after the former convent was donated to Willis’s St. Boniface Street Links outreach program, most of the first residents were alcoholics.

“Four months in, it would almost be as though somebody flipped a switch,” Willis says. “It wasn’t alcohol anymore. It wasn’t drugs that we were accustomed to. It was meth…. And none of us had any great understanding of the drug.”

Morberg House had no budget at the time. It wasn’t even a registered non-profit; that designation wasn’t approved until earlier this week. Still, Willis was undaunted. She’d do what she always did: figure it out as things went along.

That’s always been the mantra of the place, she says with a laugh — “We will find a way.” Staff say it all the time.

“We didn’t really have a plan,” she says. “We certainly didn’t have any money. It had been a dream, not necessarily an action plan.”

What she did have was a wealth of insight. For three years, she’d spent time with Faron Hall — Winnipeg’s “homeless hero,” who died in 2014 — and about 30 other people who eked out life on the riverbank.

Hall, an Indigenous man who rescued two people in the Red River — in separate incidents — was the catalyst for the Street Links organization. In a cruel turn, Hall drowned in the Red River in August 2014.

Willis says the Street Links organization and Morberg House are inextricably linked to Hall and his friends.

Over the years, Willis asked them what they needed. After all, she says breezily, they’re the experts. What would it take to get them into housing? What would it take to help them beat their addictions? They were always clear with…

She’s interrupted by a knock on the door. A man trundles in, holding something heavy in a plastic shopping bag.

“Pardon,” he says with a French accent. “I’m just visiting. I’ve brought a turkey.”

Just like Santa Claus, Willis says brightly, and waves him through to the kitchen. She explains that he’s just someone from the community who likes what Morberg House is doing. A week earlier he brought a sack of potatoes weighing more than 20 kilos.

And he’s not the only one. Another St. Boniface resident sometimes swings by with cookies. The nearby No Frills donates enough food to keep the house’s three big freezers full.

“That is the success of this place, by the way,” Willis says. “Everybody has a relationship with the people in this house. They’re very much embraced by the larger community.”

Sweet coffee and a bitter, relentless foe

The only way he could drink coffee was if it tasted like a chocolate bar. Progress, it turned out, was extremely sweet and difficult to come by.

A few long months ago, 35-year-old Myron Bateman was flat on his back on a vinyl-covered foam mat on the floor, staring at the ceiling in Main Street Project’s Martha Street shelter. He made up his mind, got yet another detox intake form and started all over again that same day.

The only way he could drink coffee was if it tasted like a chocolate bar. Progress, it turned out, was extremely sweet and difficult to come by.

A few long months ago, 35-year-old Myron Bateman was flat on his back on a vinyl-covered foam mat on the floor, staring at the ceiling in Main Street Project’s Martha Street shelter. He made up his mind, got yet another detox intake form and started all over again that same day.

At three months clean he was still living in the 30-bed detox centre, where the security cameras feed into paranoid conspiracy theories and new residents mumble about all the secrets in this place.

Over that time, he regained about 50 pounds. The sugar cravings were still there — the brain’s attempt to rebuild obliterated dopamine receptors. So were flickers of psychosis, flashes of visual hallucinations in which images of people he knew appeared before his eyes. He called them “glitches,” leftover from his years as a crystal meth-powered machine.

“I’m coming back piece by piece,” he said.

Like so many hit hard by meth, Bateman was rebuilding in baby steps, needing more time to recover than systems are normally set up to allow.

“There is a way out of this. The way out of this is to find a resource,” he said in an interview in late November. “But to be coming off crystal meth on your own, it is almost next to impossible. You need supports to help you along the way and it’s a 24-hour-a-day thing.”

He’d been given extensions of the usual 14-day detox period, and he was eventually able to get his own apartment. He was kicked out of his previous 28-day residential program after he tested positive for amphetamines, and he went back into treatment a day after meeting with a Free Press reporter and photographer.

Bateman said detox was like his “sanctuary” and that more detox beds are needed. Next year’s planned expansion of Main Street Project into the former Mitchell Fabrics building around the corner will make way for its entire Martha Street space to be devoted to detox. It’s the only program in the city that allows drug users to come in while they’re still intoxicated.

“It’s a different world we’re dealing with today,” said Tahl East, Main Street Project’s program director of detoxification and stabilization.

“We see numbers increasing, we see more and more of the same people coming back, because it’s that difficult.”

Bateman had been homeless for 18 years, since his mother died, and that’s around the time he started using meth. Back then, he considered it a “delicacy” at $40 a point — four times what it costs today. Not that he very often had to pay. For years, he was the muscle for a criminal organization he says kept him well-supplied with the drug.

“I was easily led by people all my life. I wanted to be somebody that somebody feared, which is completely stupid now, when I think about it,” he said.

“I grew up in the suburbs of St. Vital, believe it or not. I got my Grade 12 education, but I always wanted to be a badass. So I went wherever trouble was.”

Eventually, he was so strung out and unpredictable that the higher-ups told him not to come back, he said. He’d become too scary even for them. And to himself.

“Crystal meth unlocks your worst fears. That’s what it uses against you,” he said.

When he showed up at the detox centre in the summer, he was thin, sick and wanted to be left alone. His left eye was badly scratched — a tear to his cornea — from when he believed his tears were made of glass and tried to get them out.

“He couldn’t speak English,” said Main Street Project peer advocate Phil Goss, grunting wildly in demonstration.

“He scared a lot of people because of his size, but he didn’t scare me…. Basically what I was getting was, ‘I need help.’

“I knew what he was saying. I used to speak that language.”

Goss was addicted to meth in the 1960s and ’70s, and he said he never imagined the drug would take hold as forcefully as it has today. He sees potential in each of the users he encounters, including Bateman.

“I hope that one day (Bateman) can carry this on and help someone else,” Goss said. “He will. He certainly has the desire.”

Bateman has since relapsed, as so many meth users do, and Main Street Project staff say they’ll be there when he decides to return.

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Anyway, as Willis was saying, what she learned from the men on the riverbank was that their needs weren’t difficult to understand. They needed somewhere safe to live. They also needed fewer obstacles on their path to recovery.

No more waiting for treatment. No more struggling to make health-care appointments. For the most vulnerable people trying to heal, those sorts of things can be the biggest barriers.

It’s hard to get social support if you can’t show ID. It’s hard to get ID if you don’t have an address. Getting into treatment isn’t much help if it takes months to get in, and you’re barely cobbling together day-to-day life as it is.

So when Morberg House — the actual house — fell into her lap, Willis filled using those guiding principles. Get everyone a safe place to live. Help them one-on-one to access the various things they need. Go with the flow.

Above all, she thought, the place had to be a home. People needed to feel loved there, not just housed.

“We need to always be very adaptable, very flexible,” she says. “Every single person in this house has a different story to tell… you really have to be responsive to that individual and not have everything be so regulated and rigid.”

It all seems so obvious, when it’s put that way. Find out what people need; get them what they need; support them while they heal themselves. So why, amidst endless studies of best practices, does this approach seem so radical?

“We tend to always be looking for very complex solutions to seemingly complex challenges,” Willis says. “And sometimes it’s just not that complicated. Really, if you think about what goes on out there, people who end up addicted, and they end up losing everything, and they end up on the street, well, you end up in survival mode.”

The Morberg House model is what Willis calls “high-support transitional housing.” When a new resident moves in, they help build a personalized care plan. Every day, they sit down with staff to see how they’re moving through it.

If they need a ride to the doctor, staff will take them. If they just need to talk, there’s time for that, too. Each week, there are new goals, new steps they can take, learning how to carry more of the weight of their own, sober lives.

There is no time limit on Morberg House residencies. The men who are there can stay as long as they need to. When they’re ready, they can transition into their own sober-living apartment, rented in St. Boniface Street Links’ name.

How long that takes varies. Some residents move out within a couple of months; others stay more than a year. Willis has found that four to six months seems to be the sweet spot for most residents to be ready to leave.

If they relapse while out there, that’s OK. They can just move back and try again. Relapses are part of the process and staff take them in stride. The only thing that can get someone barred is violence.

“There’s no such thing as failure here,” Willis says. “It’s just, ‘OK, maybe there’s still some things we need to do.’”

What that means is that at Morberg House, there is a broader definition of success than simply not using. If clients relapse, they don’t lose everything. They don’t have to start over from scratch, the way they did back on the street.

That approach seems to work. Over time, staff have observed, clients’ relapses become shorter and less intense. Each time they climb out of one, the men seem to learn a little bit more about how to exist drug-free in the world.

“I don’t want to jinx myself,” Aitken says of his sobriety. “I’ve told (my family) so many times (that) I’m done for good, and I relapsed after I said that. I’m going to do the best that I can. That’s what I’m saying now.”

Since August 2016, more than 200 men have walked through the doors of Morberg House. At least 80 per cent of them, Willis says, are “doing well.” That doesn’t mean they never relapsed; it does mean that they are moving forward.

“It’s not the relapses,” she says, with a little shrug. “It’s how you handle them.”

Meanwhile, Willis watched as residents built their own Morberg House culture. The men tend to “bro up,” she says, forging intimate and supportive bonds that stretch across their demographic gaps. They look out for each other.

Not long ago, one resident returned to the house intoxicated. While a night staffer dealt with the situation, residents gathered to affirm that the house needed to remain sober. They are invested in its success.

That, Willis says, is the key to it all. For many residents, everyone in the home — staff, each other — becomes the “family they never had,” she says. A family that understands addiction, that can look at it together, without judging.

“If we could take an approach where, let’s join hands as a family and see how we get through this, that’s far better than a very institutional approach where you have one model for everybody and very scripted programs,” she says.

Plus, it’s cheaper than an institution. For each occupied bed, Morberg House receives a little over $700 from social assistance; enough to cover one pay period. The rest of its budget comes through a patchwork of private donations.

To Willis, that funding model means freedom. Government money comes with a lot of paperwork, and various strings attached. Funded on its own, Morberg House is free to evolve, to do what staff think needs to be done.

Still, the house isn’t flush with cash. So they find a way. To staff it, for instance, Willis created a partnership with Brandon University, to give practicum space to psychiatric nursing students. Two are scheduled to arrive in February.

To think it started with just a free house, some chutzpah and a vision. But if you have a house, Willis says, and can engage the community, then “wonderful things happen.” In this way, Morberg House isn’t only a place; it is also an invitation.

“It’s a really unusual model. I know that,” she says. “It’s different. And it’s very simple, really. We just went out and found ways to make this work. Who would have thought that community partnerships would be so easy to find?”

Which brings her to another point. All around the meth crisis hangs the spectre of money: how much it is costing Manitoba and how much it will take to stem the tide. It seems, sometimes, as though every resource is stretched thin.

Willis sees it differently. There’s enough money out there, she thinks; it’s just not always spent in the right places.

At the end of the day, it can be simple. Figure out what people with addiction need to survive. Then get them a safe place to live and fill it with love and time — to heal, to try. Time to build a life that can hold them.

“Don’t overthink the solutions,” Willis says. “We’re all human beings. We all have basically the same human needs, even the most fractured person. Can we put them all back together? I don’t know. But even the most fractured person who comes through here is much better by the time they leave.”

It takes a village to raise a child, as everyone knows. What is less often said is that we still need that village, long after we’re grown.

•••

Dane Bourget surveys the room, counting as he looks around. Eight people, him included. It seems too low.

Almost every day, news headlines scream about the rampant rise in meth use in Winnipeg and the random, shocking violence it causes. The mayor and police chief recently joined forces to warn about a dire strain on municipal resources they blamed directly on the drug.

And yet, at this self-help meeting — the weekly gathering that’s helped the 36-year-old Bourget stay away from meth for the past four years — there are only eight people present. Where are the rest?

“I just kind of got the feeling that something more needed to be done and I needed to create something different,” Bourget says. “If we’re kinda sitting back waiting for everybody to come to us, it might never happen.”

He’d heard about Toronto’s withdrawal management centres and their direct phone lines that connect people to the quickest available treatment. There wasn’t anything like that in Winnipeg yet, and he thought it could be a key piece of the puzzle.

So in August, Bourget launched a different method to reach meth users directly.

Along with Robert Lidstone, his former treatment-centre roommate, Bourget set up a Facebook group and founded Jib Stop, a volunteer-run phone line staffed by about 10 Winnipeggers who are all in recovery from meth addiction.

They got some money from a private donor to buy a cellphone they now pass around, returning callers’ messages within 24 hours to guide them through the gaps in Manitoba’s addiction-treatment and recovery systems.

The phone number is 204-904-7867 (STOP). That’s where people can call to be connected to help.

The biggest issue, Bourget says, is the wait. Even since the September opening of new walk-in Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine clinics, users trying to quit can still be left in the lurch.

“It’s hard to navigate the system. It’s hard to wait. It’s probably the biggest cause of people not recovering… is the wait times,” he says.

As of Nov. 30, maximum wait times for AFM residential treatment centres in Winnipeg were 46 days for men, 255 days for women. Coed treatment centres had waits ranging from 39 to 90 days, AFM’s figures showed.

For youths, there was a four-day waiting period. An AFM spokeswoman said not everyone requires residential treatment, and that waits for non-residential treatment programs are shorter — from a day or two to a few weeks.

Making the most of that time is important — and that’s where the phone line comes in. Since it got off the ground a few weeks ago, Jib Stop has mostly received messages from family members of addicts. Volunteers point them toward existing community resources while offering the comfort of a listening ear.

They want to help people stay hopeful even if they face a long wait for treatment, because they both know how important it is to have someone to talk to. Having someone who understands what you’re going through is a key.

“We want to be able to help them figure out a strategy,” Lidstone says. “We really see all the images of despair and hopelessness, and we know that can de-motivate people. And motivation is so crucial with recovery from this drug.”

But their goal is to hear from addicts. On that end, they have plans to expand — in the future, they’d like to set up a buddy program, matching users with Jib Stop volunteers who can go to meth recovery meetings with them.

“There’s just kind of a magic to what happens between peers that we think is an important part of the puzzle,” Lidstone says.

He credits Bourget with helping him in his recovery — he’s about six months sober after using meth on and off for 10 years — and they both want to do what they can to support other Manitobans going through the same thing.

“I know from personal experience the suicidal ideation that goes on after a period of meth using, just the utter self-loathing, the despair. I know how that feels,” Lidstone says. “It’s made all the difference to me to have people like Dane in my life.”

For Bourget’s part, he says he feels a need to pay it forward. Just like others did for him when it was his time to struggle out of addiction: a chain of compassion, stretching back and forward, leading the way to a healthier life.

“The only reason why I’m here is because other people who got better spent time on me,” he says. “They stuck around to save my life, so it’s the minimum I can do, you know?”

It will take a lot more work to heal a province from the meth epidemic. Everyone the Free Press spoke to has something on their wish list — more detox beds, shorter wait-lists for treatment, more long-term rehab options.

Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman wants to see a national strategy to deal with illicit drugs, a more secure border to prevent substances from coming into Canada, and more resources.

“It’s meth today. It could be another drug (in) years to come,” he says. “Unless all governments put greater resources into helping with mental health, addictions and homelessness, we’re not going to be adequately addressing the crisis we’re seeing right now.”

Those are the big-ticket items, the ones that need to shift entire complex systems. But the change can also begin closer to the grassroots. It can begin in neighbourhoods and in workplaces. It can begin with outstretched hands.

Take work, for example. Before he was caught in meth addiction, Millard was a successful consultant. The drug took his livelihood and most of everything else. He realized it would take years for people to trust him again.

While he worked to get back on his feet, a local construction company aware of his situation, offered him a job. Millard’s eyes glisten as he talks about what it meant; he works hard to prove that faith was well-placed.

A job, an invitation to work, a chance to rebuild pride in one’s life. To get out of addiction, he says, a person first has to want it. But they also need someone on the other side, he adds, who is waiting to accept them.

“I started thinking about all the people that have come across my path in recovery, that have just believed in me a little bit, and that little bit was enough to get me to the next stage,” he says. “Some of them were paid to do it. A lot of them were volunteers. My current employers took a chance on me when I was living in a sober-living facility.

“How do we make the meth epidemic a human problem?” he continues. “Acknowledge there’s a stigma, but help the community understand that there’s something that everyone can do.”

Now, it seems, that message is sinking in. As the year speeds to its conclusion, the tone of some people on the front lines of the meth epidemic is noticeably changing. Hope is creeping in.

In September, AFM educator Fandrey gave a presentation about meth to a trio of Free Press reporters. At the time, she was frank about Manitoba’s systemic progress in stemming the crisis.

“We’re in survival mode,” she said then.

Just three months later, Fandrey was far more optimistic. The tide seemed to be turning. She was about to testify before the House of Commons’ hearings about meth, initiated at the behest of Winnipeg Liberal MP Doug Eyolfson.

At community meth-information meetings and workshops across the city, she’d seen how professionals from different sectors — law enforcement, health care, non-profits — were trading notes. People who can help, forging connections.

Across Manitoba, bridges are being built. Slowly, at first, or at least not entirely visible to the public. But their bones are rising.

“We are starting to be a bit more proactive,” she says. “We still have a ways to go, and I think everybody would acknowledge that. But I don’t feel quite as overwhelmed as I did in September.”

One by one, changes started to ripple through systems. In September, the first RAAM clinic opened in Winnipeg, couched within the 24-hour Crisis Response Centre on Bannatyne Avenue. Four more locations — another in Winnipeg and three in Selkirk, Brandon and Thompson, respectively — followed in subsequent weeks.

Based off a popular low-barrier model in Ontario, the clinics aim to streamline the process for people seeking help for their addictions. Rather than bounce from emergency department to general practitioner or counsellors, patients get an initial assessment and a nudge in the right direction — to detox, treatment or anywhere else they might need to go.

The clinics are not a perfect solution. Their limited schedules have drawn skepticism from both politicians and the general public. The centre on Bannatyne, for example, is open three afternoons a week for two hours at a time.

One nurse, who spoke to the Free Press on condition of anonymity, says she hesitates to even recommend the RAAM option to meth users.

“Most of these people don’t have a phone or a watch. They don’t know what time it is. They don’t know what day it is,” she says. “It seems like such a ridiculous idea, like ‘OK, we’ll offer you services, but you can only come in for this very tiny, short period of time.’”

Dr. Erin Knight, medical director for the addictions unit at Health Sciences Centre, says RAAM clinics’ volume of patients can ebb and flow, along with their hours. The clinics see an average of eight people a day during walk-in hours; about one-third of them cite meth as their primary drug.

“We have clinics sometimes where we do, unfortunately, have to ask people to return to the next clinic, but we also have clinics where we don’t fill up,” she says, noting they often meet with patients for longer periods of time than scheduled.

It’s too early to tell whether the clinics can make a dent in the problem, whether the province will be any better off six months or a year from now because of them, Knight says. But they are a template for changes yet to come.

“I think one of the key things with the RAAM launch was that this is kind of the first step of rapid access in Manitoba,” she says. “It’s never been intended that this is where it’s going to end.”

While the province has touted some evidence-based approaches, such as the clinics, it has decried others, such as supervised-consumption sites. A WRHA-led group is studying the effectiveness of the latter option now and its findings are expected by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, other systemic changes are pending. The Manitoba government has issued a request for proposals seeking one or more providers to build 15 more residential beds for mental-health and addictions treatment.

On Tuesday, all three levels of government announced the creation of a new meth task force, something advocates had hoped for. Its first report is due out in six months, though implementation of its recommendations may take longer.

Any amount of time can seem like an eternity to people desperately trying to hang on. Still, it means we’re further ahead now than we were.

“There are enough bright lights,” Fandrey says. “Enough of them are out there to make me think that we’re going to find a way. And I’m hoping that way becomes the standard operating procedure that we will carry on into the future.”

In the end, she says, the keys to that evolution are simple. It’s not the services people fall through; it’s the cracks.

“Always communicate well,” she says. “Always transition better. And get better at meeting people where they’re at.”

•••

Back at Morberg House, the phones keep on ringing. A man calls from prison, hoping he can move in after he gets released on Christmas Eve. There are calls like that every day, referred by hospitals, rehabs or the Main Street Project.

Sometimes, men turn up at the front door, tears on their cheeks, nowhere else to go with detox full, a rehab bed weeks away. Even without an open bed Willis takes them under her wing like a den mother, at least for a meal and a shower.

It’s hard to turn people away, she says. But they have to. Morberg House has become a desirable place to be.

The day rolls on, a casual sort of chaos, a dozen individual needs coming together and moving apart. One house staffer gets the donated turkey ready for dinner. A visitor arrives to take one of the residents, a friend, out for lunch.

Willis has good news for Ricky Aitken: he’s been accepted into a new baking certification program at Red River College. The only problem is the location in a blighted patch of Main Street that Aitken calls Hell City.

“So even though it’s the opportunity for you of a lifetime in terms of schooling, you’ll have to think about your recovery, and how vulnerable you are to relapse,” Willis says, as she hands Aitken the acceptance letter.

Aitken nods, solemnly. He spreads the letter on the table in front of him and ponders it carefully, as if it were a royal proclamation. Or as though it might simply vanish. When he looks up again, his eyes are guileless and shining.

“No one’s ever done this for me before,” he says.

Maybe that’s it, that’s the spark. That’s the magic that makes Morberg House work, and not just that house, but all places where people find healing. It’s the open hands, the spaces carved out to be held, the words of compassion.

Building this sort of model isn’t easy. It takes a lot of love. It takes a lot of patience. It takes a lot of people who are willing to go into the trenches and belay the ropes to help others climb out. Neighbours, advocates, recovered users.

But the cost of not trying is far higher, in both money and hope. The price tag of not trying can be seen in the broken lives struggling daily on Winnipeg’s streets. Trauma that digs sharp claws into everything it touches. Fear. Despair.

Winnipeg was not submerged in crystal meth overnight. It will not rise above it overnight, either. But with each day that passes the road out becomes a little wider, built by a multitude of Manitobans who want only to keep trying.

Willis has a meeting this week — when was it again? Her calendar is so full these days — for which she is very hopeful. This could be the one, she thinks, that helps pave the way for her next big vision: an apartment block.

That’s the dream, she says. If St. Boniface Street Links could manage an entire building, it could turn several floors into transitional, supported sober housing. Other floors could be used for various programs and staff.

It would be an enormous undertaking, she knows. But it would open up so many more options. They could help so many more people. They could expand their services to include women, now one of Willis’ most pressing goals.

“I just think we could do it,” she says. “I just need like-minded people. If nothing else, our outcomes speak for themselves. And that’s the people who have been through here. You don’t have to take my word for it — this works.

“Does everybody leave here fully healed?” she continues, and answers her own rhetorical question. “I don’t know if any of us are fully healed, we’re all on a journey of some sort. But we leave here much more fully positioned to do better.”

With that, she leans forward, narrows her eyes to a hawk-like focus, and raps her fingers on her desk.

“Yeah, I want an apartment building,” she says.

In this moment, warm in this house built on a foundation of community and dedication, surrounded by men who call her a surrogate mother, nothing seems more evident. She’ll get it; somehow, it’s going to happen.

Willis leans back in her chair, and a sly smile dances over her lips. “I wouldn’t bet against me,” she says.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, December 21, 2018 7:57 PM CST: Fixes misspelled name

Updated on Friday, December 21, 2018 8:01 PM CST: Fixes typo