Anthropologist known as a great storyteller and adventurer

Virginia Petch dedicated life to heritage preservation, education and communication

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/02/2019 (2590 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Asked to describe Virginia Petch, the first words friends and family are drawn to are “passionate,” followed by “great storyteller.”

Petch, who died Dec. 8, 2018, at 73, from ovarian cancer, was an anthropologist and consultant. She is survived by her mother, three sisters, two sons, three granddaughters, nieces, nephews and, as her obituary noted, “many professional colleagues.”

Petch possessed a canny knack for telling stories about a dig site. She’d go far beyond what trowels and brushes exposed in wafer-thin layers of dirt. To her, those layers were like onion skin pages in a rare book.

She incorporated aspects of oral history and tracked the centuries of cultural marks left on the land. She invariably wrapped the stories up in a punch line that featured something funny, often about her own peculiar role in resorting the role of prehistory to people and their places.

In one of the eulogies Petch helped arrange for her own funeral, longtime friend and fellow anthropologist Janet McKinley noted her friend’s wry side.

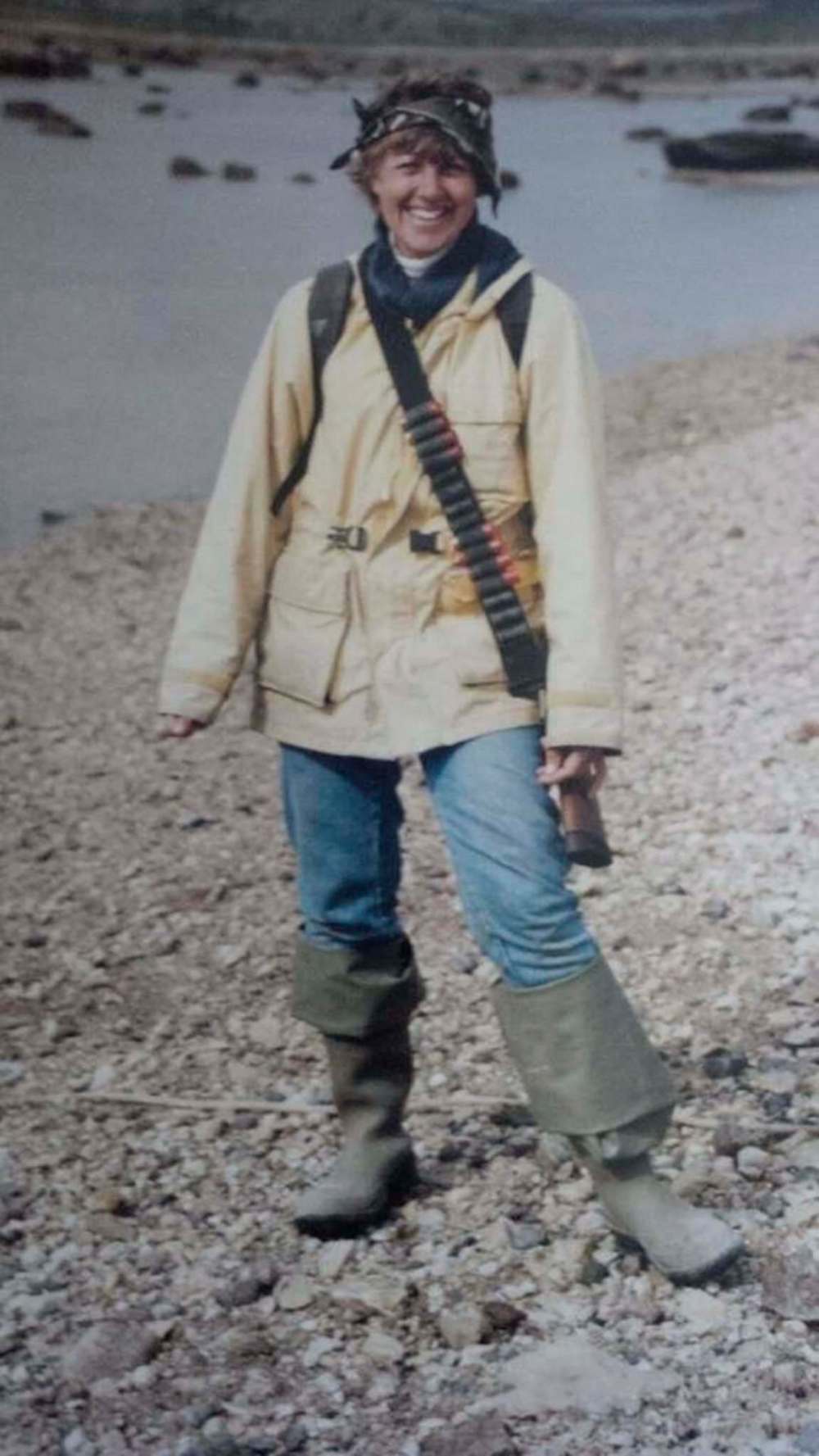

“She also demonstrated a fierceness — field work in northern Manitoba and elsewhere is not for the faint of heart. Conditions which were often difficult didn’t phase her. She was skillful, sensible and had a good sense of humour,” McKinley told friends and family. “We teased her about her Rambo picture. With a bear gun and belt of ammunitions slung over her shoulder, she was ready for anything.”

Two months later, the sentiment holds true, Petch’s son, Christopher, said: “That Rambo picture pretty much summed it up.”

Petch was loving and caring, and very active, he said. “Growing up, we were always tramping through the bush, picking blueberries and stuff. She was very ‘into the wild.’”

One summer — in a effort that helped her land one of her many academic credentials: bachelor of arts honours, master’s in education, PhD in anthropology — Petch took her two teenage boys to a site in the Turtle Mountain area.

“She dragged us around, digging through all these layers of sediment salts, salt that people used to collect,” Christopher said.

In anybody else’s hands, it might have made for dry reading, but those salt flats helped bring to life a forgotten chapter before European contact.

In Voyages: Canada’s Heritage Rivers, author Lynn E. Noel credited Petch with drawing public attention to seven obscure anthropological sites from a single northwestern Ontario lake.

“Some sites like the spectacular cliff paintings at Artery Lake are impossible to miss… we meet the stone canoes of the memegwaysiwuk (the little people), the many legged misshupeshu, the water lynx. The stick-figured shaman held the otterskin bag in his hand, squiggling lines (rising up) like lightning above him. ‘They’re power lines,’ said Virginia. ‘He can call down power.’”

By 1998, Petch’s seamless cultural infusions also earned her accolades, with the Prix Manitoba Award for her dedication to heritage education and communication. She founded her own land-use and cultural consultancy out of necessity in 1992: Northern Lights Heritage Services, which worked with Intergroup Consultants Ltd. on Manitoba Hydro projects throughout the North.

“That is exactly what I was trying to get across: she was meeting with First Nations long before it was recognized,” Petch protégé, Amber Flett, said in a recent interview. It fell to Flett, as past president of the Manitoba Archaeological Society, to write a tribute to her mentor in the society’s first newsletter of 2019.

“When I think about Virginia, one of the first things I think about is her involvement and her connection with Indigenous people,” Flett said.

Her own friendship with Petch came from a chance encounter Petch had with a bush pilot, who told the archeological consultant about a student with a brand-new undergrad degree in anthropology who was working as a fire ranger. Petch and Flett started an email exchange that led to Flett’s first real job in anthropology, a field in which she still works.

“One of the reasons she hired me was she liked the fact I was working with Indigenous people,” Flett said.

In her eulogy, family friend Janet McKinley shared Petch’s adventures from her days on a site north of Churchill.

“She told stories about bouncing along Hudson Bay near the shore in a zodiac (boat) for two hours to reach the Hubbard Point site each day of (one) field season. And then two hours back at night,” said McKinley.

“The next year, she set up camp at the site, surrounded by an electric fence to discourage the polar bears. She remarked that she knew what it felt like to be in a zoo, with the polar bear circling and starring at the humans.”

Petch was born Virginia Kishynski, in Winnipeg in 1946, and grew up in the tiny mining outpost of Balmertown, Ont. It was where she found her love of nature and the love of her life.

She married Donald Petch when she was 20. The couple moved to Kenora, Ont., where both were employed as teachers.

In Kenora, Petch found her unique perspective on anthropology, incorporating narratives and evidence about people and place. Her work in the last 20 years for Indigenous groups and for Manitoba Hydro produced tens of thousands of pages of documentation that has yet to be fully put to use.

She had a hand in helping set up a cultural centre at Buffalo Point First Nation and a museum in Tataskweyak Cree Nation. She put in countless hours on the Pimachiowin Aki nomination for World Heritage status, and as far back as the 1980s was deeply committed to recognizing Indigenous contributions to the country’s heritage.

Her 1998 PhD chronicled the relocation and loss of the Sayisi Dene homeland in northern Manitoba.

When declining health narrowed her focus to her own backyard, Petch turned to Facebook, entertaining friends with comical verse about her pets, and the wildlife she witnessed.

Last June, she posted a series of four photos of her dogs and some galloping verse to recount what probably took place while she was away at the doctor’s office: “I think this is what happened… I’ll never know for sure. But picture this: two frisky dogs in a garage with nowhere else to go…”

alexandra.paul@freepress.mb.ca