‘A pattern of incompetence or corruption, or perhaps both’ Public-sector malfeasance expert says Winnipeggers deserve an explanation for waste of taxpayer dollars in city’s public works department

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/02/2022 (1386 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The anti-corruption expert grew increasingly concerned with each passing example of costly and confusing construction projects ordered by Winnipeg’s public works department — year after year, intersection after intersection.

Kevin Gillese stopped the presentation halfway through — he’d seen enough.

“The materials you’ve shown me are extremely disturbing. They suggest a pattern of incompetence or corruption, or perhaps both… The patterns shown are over a long period of time and there’s no obvious rhyme or reason to what’s being done,” Gillese said.

“The extent and the magnitude is so great that it staggers the imagination. It suggests something very, very wrong in the way intersection engineering is being done in the City of Winnipeg.”

Gillese, a retired lawyer, spent 25 years working in the anti-corruption sector, with a particular focus on public procurement contracts for highway and infrastructure construction. For more than a decade, he worked for the British Columbia Public Service.

The Free Press was connected with Gillese in late January by Gerry Ferguson, a recently retired professor at the University of Victoria, who served on the United Nations Working Group on Anti-Corruption.

Gillese agreed to review the work of independent researcher Christian Sweryda, who has been studying traffic-related issues in Winnipeg for more than a decade. Most recently, Sweryda’s research has focused on patterns of alleged financial abuse by the public works department, specifically involving traffic light construction projects.

Sweryda’s findings are the subject of an ongoing Free Press investigative series: Red Light, Green Light, No Oversight. This is Part 2. (Read Part 1 here.)

Gillese said anti-corruption specialists look for wasteful patterns of behaviour that can’t easily be explained by “mere incompetence”.

“And this does have that suggestion,” Gillese said.

It was the same presentation Sweryda gave to Coun. Matt Allard (St. Boniface), the chair of the public works committee. Alarmed by what he saw, Allard connected Sweryda with city auditor Bryan Mansky.

On Wednesday, Allard will move a motion calling for an audit into the public works department at the Riel Community Committee.

“Late in 2021, I was shown a presentation by (Sweryda)…. I’m very concerned by what I saw. I have asked for an audit and offered my support to the city auditor if his office requires more resources to investigate,” reads a draft of Allard’s motion.

“The presentation was so compelling, and it’s possible implication so troubling, I have met with (Mansky) on this matter twice now. Their office is investigating this issue.”

Allard told the Free Press that where there have been improvements to traffic safety in Winnipeg in recent years, they have largely resulted from Sweryda’s efforts.

“In terms of his understanding of the issues, at a high level, I don’t know if there’s anyone who understands road safety and the regulatory framework better than him,” Allard said.

“I think (an audit) will likely confirm that (Sweryda) was right again.”

A second city councillor — Shawn Nason (Transcona) — also supports an audit. He sat through a condensed presentation of Sweryda’s work and walked away concerned.

“Looking at what he presented… the subtle changes he found and the work being done year over year, much of it didn’t seem warranted from public works,” Nason said.

“I don’t think there should be any harm or fear in making sure we’re being as efficient as possible with the taxpayer dollars that are entrusted to us. But there seems to be a strong resistance to change.”

On Sunday, Coun. Scott Gillingham (St. James), who chairs the city’s finance committee, issued a press release calling for a public hearing into Sweryda’s findings — just days after the Free Press brought them to light.

The Free Press shared Sweryda’s research with Todd McKay, prairie director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation.

“This is really concerning on a number of levels… I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like this. The research here is unbelievable… If the question is, how significant is this story, I would suggest very,” McKay said.

“There needs to be accountability for this. For every single change that was made, they need to show why it needed to be done, undone, redone. It’s hard to imagine you could have an explanation. And if there isn’t an explanation, there needs to be consequences.”

The Free Press offered to walk the City of Winnipeg through Sweryda’s findings if it made manager of transportation David Patman and Director of Public Works Jim Berezowsky available for an interview. The city declined.

Instead, it provided a written statement extolling the professionalism of its traffic engineers, adding that it is now in the process of updating its transportation design manual, as well as design standards for traffic signal infrastructure.

A city hall source, who asked to remain anonymous, said the problem in the public works department is “multi-faceted and systemic,” resulting from staff who resist reform because it would expose significant problems they have caused or ignored.

That sentiment was echoed by McKay, who said Sweryda’s findings point to deeper, structural problems at city hall.

“One of the bigger things I’m seeing here is a cultural issue… This seems to be widespread and cultural. And to me, that is more concerning than the nuts and bolts and yards of concrete being wasted,” McKay said.

“Very rarely is that a problem in only one place. And we’ve seen enough problems at city hall in Winnipeg over time that we know it’s very, very unlikely this infection is only in one appendage. To me, that’s the biggest concern: what does this say about the culture at city hall?”

In April 2019, the Free Press reported on widespread time theft and gross workplace misconduct among inspectors in the city’s property, planning and development department. Following an investigation, the city fired eight inspectors and disciplined seven others.

The Free Press also shared Sweryda’s findings with Yasser Hassan, a professor of Transportation Engineering at Carleton University, who chairs the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Before emigrating to Canada, Hassan was responsible for approving most traffic and road engineering projects in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates. He said he would not have signed off on much of the work Sweryda uncovered.

“Public dollars are not that many. When you’re going to spend a public dollar, you really need to make a case that this is the biggest bang for your buck,” Hassan said.

“There must be a record to justify this. And if there is no documentation, then obviously they have no justification for what they’re doing.”

To date, Sweryda has spent hundreds of hours completing an in-depth analysis of 513 of Winnipeg’s 681 traffic-light controlled intersections – roughly 75 per cent.

Sweryda believes he’s uncovered a systematic pattern of construction projects with significant costs to taxpayers but little practical benefit.

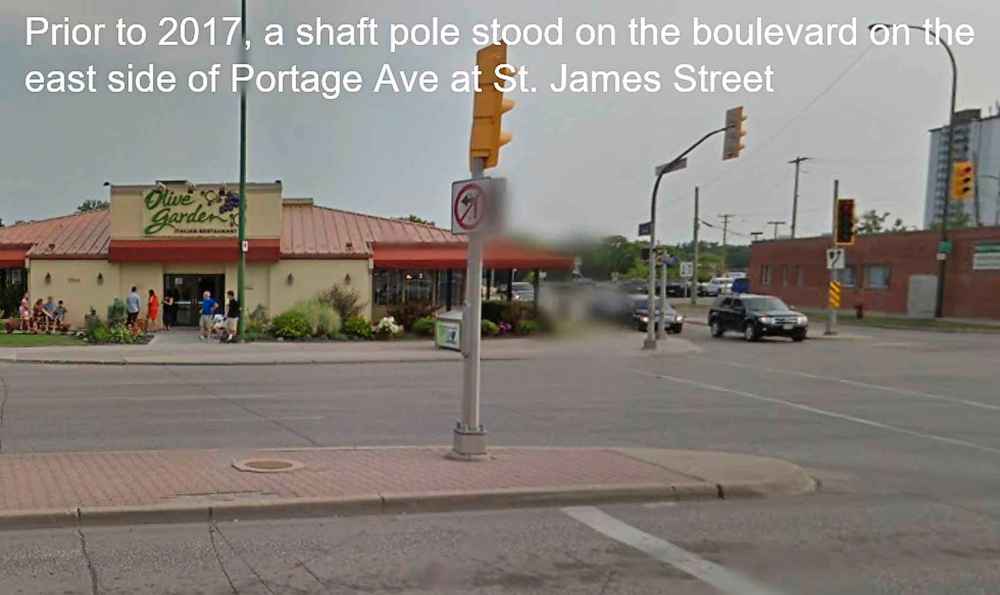

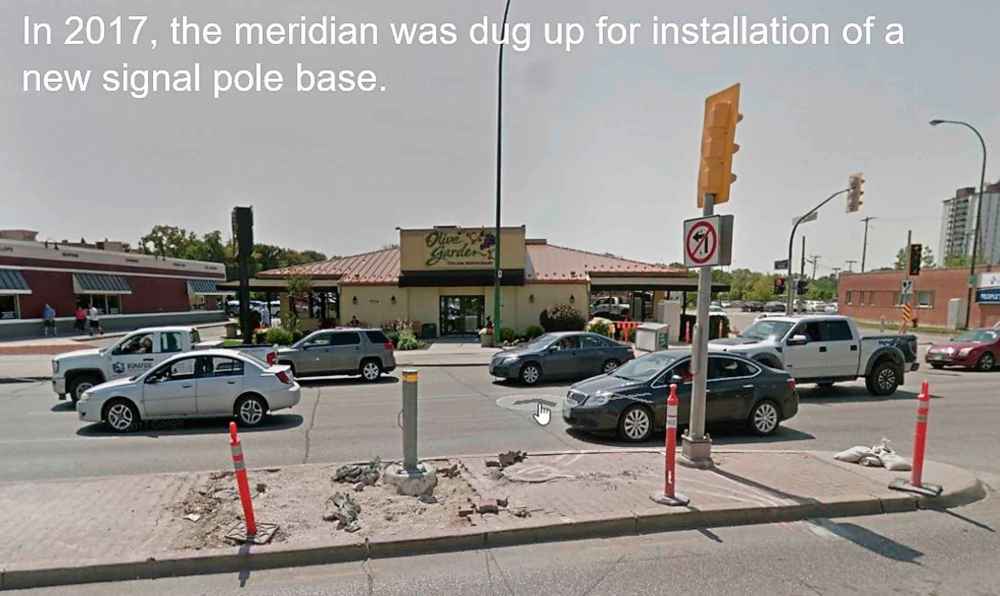

An example of wasteful practices is the intersection of Portage Avenue and St. James Street, which underwent a rebuild in the summer of 2017.

Traffic poles were replaced and moved short distances at every corner — a considerable undertaking, which required tearing up concrete, digging new holes, swapping out equipment, pouring fresh concrete and rewiring below the street.

Sweryda said some of the work, particularly on the north side of the intersection, may have been justified, but moving every single traffic pole wasn’t.

The traffic poles on the medians were moved further away from the intersection — the opposite of what’s often seen in other areas of the city — and no work was done on the boulevards that would justify the changes.

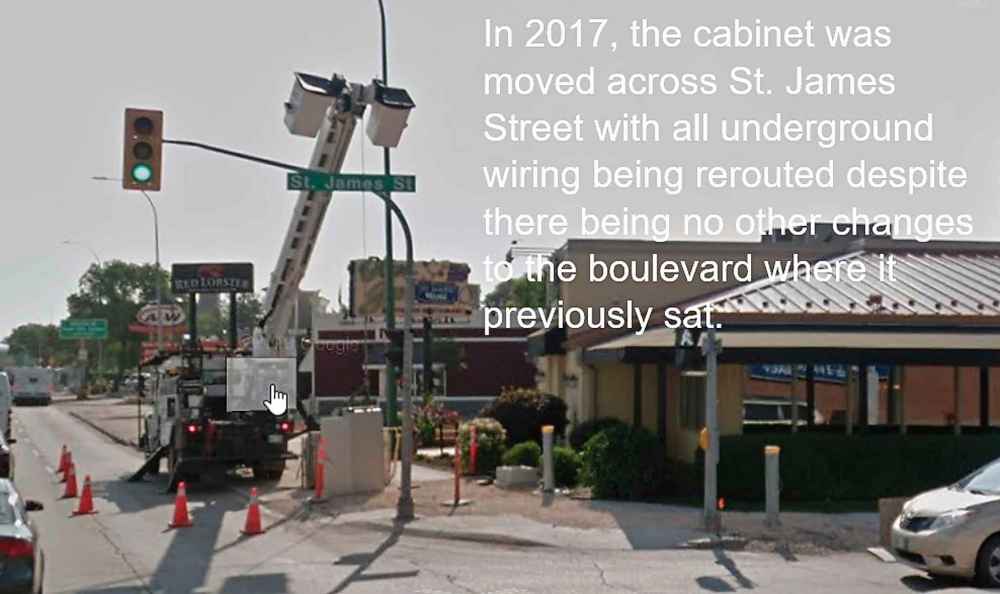

The control cabinet, which contains signal-light circuitry, was moved across the street, in front of the window of a nearby restaurant – a task that required the use of heavy machinery.

Sweryda believes that either incompetence led to inflated construction costs, or there was a deliberate attempt to increase the workload with no concern for the public purse.

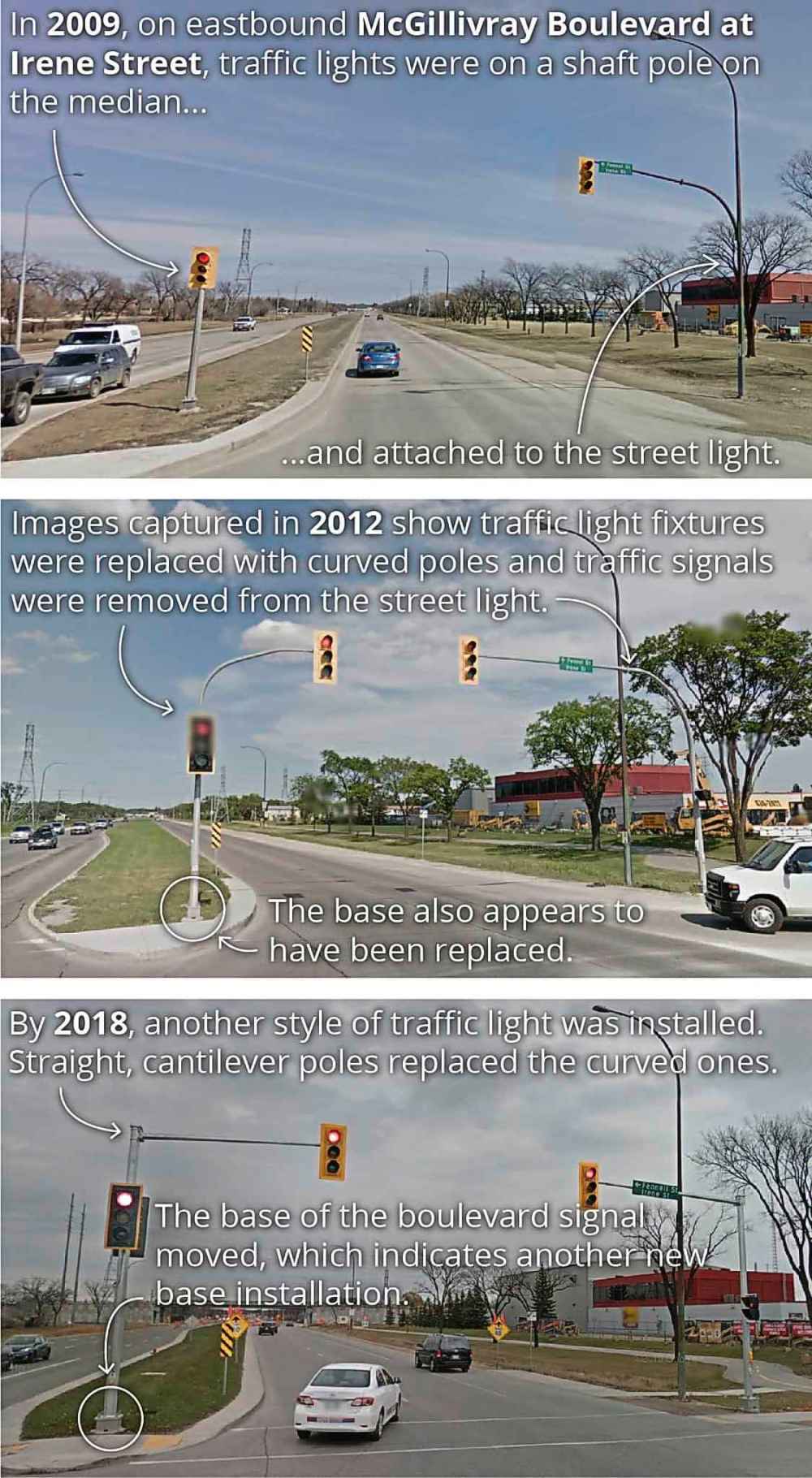

Or take McGillivray Boulevard and Irene Street. Around 2011, the intersection was rebuilt and all new traffic control devices were installed.

Workers also installed new bases for all the traffic poles, which required tearing up concrete, digging new holes, swapping out equipment, pouring fresh concrete and rewiring below the street.

The joint-use poles at the intersection, which see traffic arms bolted onto a street light pole to save resources, were split, resulting in the installation of additional poles.

Unless they are damaged or defective, traffic control materials have a lifespan of many years, if not decades. In 2018, work crews were back at the intersection for another rebuild.

The traffic poles (davit-style with a curved arm) were swapped out for new ones (cantilever-style with a straight arm). The only difference between the two designs is aesthetic.

The new traffic poles were placed onto new bases, which — once again — required tearing up concrete, digging new holes, swapping out equipment, pouring fresh concrete and rewiring below the street.

The locations for the new traffic poles were all marginal distances from their original locations. Google Street View captured the project underway, and in some cases, the new bases almost look as if they’re touching the old ones.

Sweryda filled a freedom-of-information request seeking all records and communications related to the work. The response left him with more questions than answers, particularly about the department’s record-keeping practices.

The city provided design drawings and work crew instructions, saying the project had been “completed as part of the McGillivray street road rehabilitation.”

But the response did not explain why the work was done or how it had been justified, aside from noting that “changing to a cantilever style pole was the standard practice at the time.”

The explanation made no sense to Sweryda, as purely aesthetic changes to traffic materials did not seem like a sufficient justification for the amount of work it took to install them.

He also knew the city was continuing to install davit poles at other intersections — such as Peguis Street and Reenders Drive — at the same time.

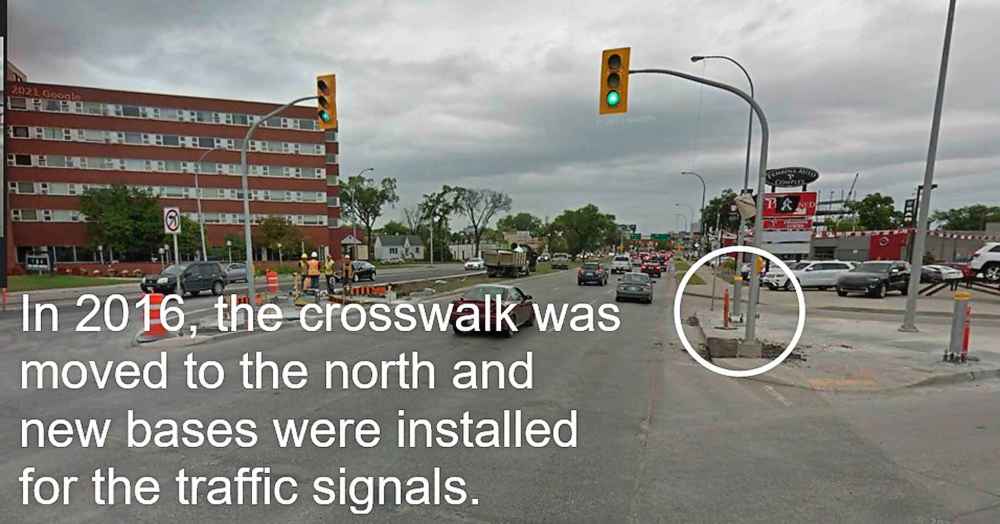

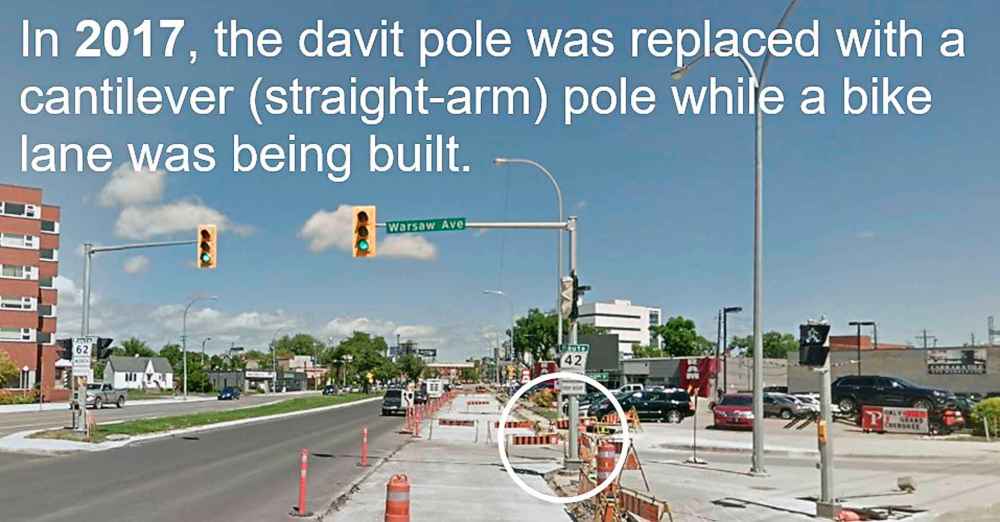

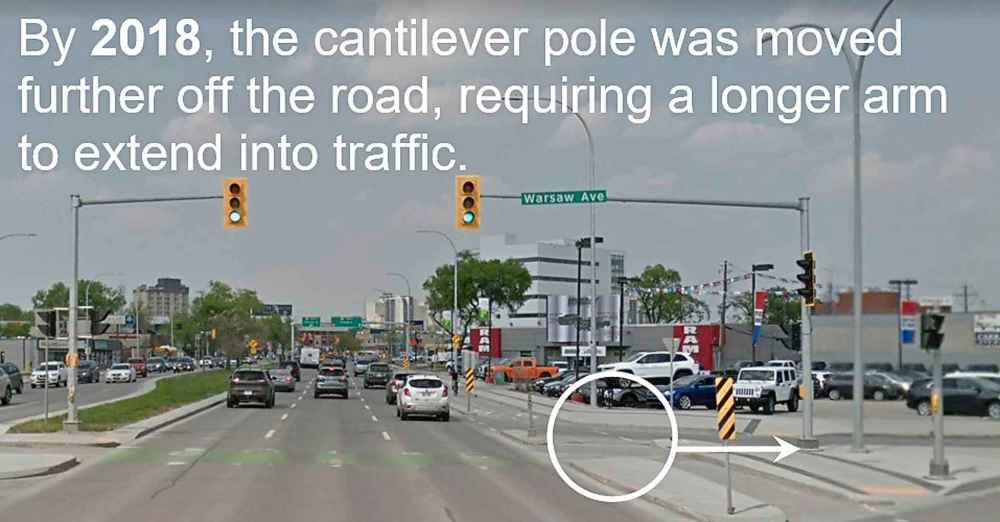

Then, there’s the northeast corner of Pembina Highway and Warsaw Avenue. In 2016, during an intersection rebuild, work crews installed a new traffic pole in the path of a bike lane that was slated to go in months later as part of the same project.

When the work crews returned to install the bike lane, they had to remove the traffic pole they’d just installed, only to put in a new one a few feet further back — swapping out the materials in the process.

Sweryda has also uncovered cases of work crews installing permanent traffic control materials at temporary intersections in direct contrast to practices seen in other major Canadian cities.

Anti-corruption expert Gillese said the question of whether incompetence or corruption is to blame is not as important as one may expect, as the end result of the two are the same: a drain on taxpayer resources and erosion of public trust.

“Incompetence can be worse because you can get not only the wasting of resources, but also safety issues you wouldn’t get from someone who is competent but corrupt,” Gillese said.

“Whether this is incompetence or corruption, the question is: What the heck is going on here? And somebody has to give the taxpayers of Winnipeg a decent explanation.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Wednesday: Part 3

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, February 22, 2022 6:07 AM CST: Adds cutline

Updated on Tuesday, February 22, 2022 11:24 AM CST: Concrete was poured, not cement.