Tripped up, locked up They're called 'crossover kids' — teens caught between child welfare and criminal justice institutions with no hope of getting ahead

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/12/2017 (2905 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

At 17, she set a goal for herself: never spend another night in jail.

It was a promise she never managed to keep. Not after what transpired in the fall of 2016, when she picked up a kitchen knife and angrily stabbed it into the counter before taking it into the bathroom, holding the blade against her left forearm and cutting into her own flesh.

“I had the knife so I could try killing myself,” she explained to a provincial court judge who asked how the teen wound up pleading guilty to possession of a weapon after she had harmed herself.

As a foster child living in a city group home, with a history of being sexually abused and now surrounded by people she hadn’t yet grown to trust, the teen amassed a criminal record composed entirely of “group home-related incidents.” So, by picking up the knife — “brandishing” it, the Crown attorney would later argue — the teen had violated her court order. She broke the law, and she was booked into youth jail because of it.

By the time she received her sentence of 20 hours of community service for the weapon charge and an earlier assault charge that stemmed from a tussle with her group-home worker over a fanny pack containing money and medication, the foster child had spent 25 days in custody at the Manitoba Youth Centre in Winnipeg.

She is one of Manitoba’s crossover kids – foster children who end up entangled in the criminal justice system, often through a revolving door of onerous police- and court-imposed conditions and repeated violations. Advocates say the system is setting them up to fail and ushering them from one state institution into another, with lasting consequences.

For years, Manitoba has had some of Canada’s highest rates of child apprehension and youth incarceration. But the province has only recently started tracking the overlap between kids in the child welfare system and kids in jail. Most young people incarcerated at the youth centre are also involved with Child and Family Services, a Free Press freedom of information request revealed.

From August 2016 – when the justice department started collecting such information – and October 2017, about 2,317 youth spent at least some time booked into the youth centre. More than 60 per cent of them, approximately 1,433, were in CFS care.

An upcoming in-depth study by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy will, for the first time in this province, examine an entire cohort of so-called crossover kids. Researchers hope to shine a spotlight on cracks in the two systems and help point the province toward potential solutions. British Columbia and Ontario lead the country in raising the alarm about crossover youth and making gradual changes to stop the cycle. Research out of those provinces has shown respective overlaps between child welfare and youth justice of about 50 per cent in Ontario and 40 per cent in B.C..

Assessing the severity of the problem

For the first time, Manitoba researchers are taking an in-depth look at the overlap between the two state-run systems. Mirroring a 2009 study from British Columbia, they are delving into provincial data to follow all of Manitoba’s children in care who were born in 1988. The aim to find out how, and why, many of them ended up in the criminal justice system.

For the first time, Manitoba researchers are taking an in-depth look at the overlap between the two state-run systems. Mirroring a 2009 study from British Columbia, they are delving into provincial data to follow all of Manitoba’s children in care who were born in 1988. The aim to find out how, and why, many of them ended up in the criminal justice system.

Equipped with child-welfare data up to 2014-15, the researchers won’t be able to see any information that identifies the youth, who’ll be 30 years old by the time the study is expected to be released next year. They hope to get to the root of the issue through their research, which was requested by the healthy child committee of the provincial cabinet in 2016, and is being funded by the province.

“We’ll be able to follow them not just into youth justice involvement but into young adulthood,” says Marni Brownell, senior research scientist at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and professor of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

Brownell is working with University of Manitoba law Prof. Lorna Turnbull, who says she hopes the work will lead to evidence-based public policy.

“I hope the results will be to inform policy makers when they think about, ‘What are we doing and could we do it better?’” Turnbull says. “We don’t have that evidence right now. The study, we don’t know what it’s going to give us, but it’s going to give us information that surely can inform policy.”

Change has been slow despite in-depth research about crossover youth in B.C. and Ontario.

The federal government is paying for a four-year pilot program in four Ontario cities – Toronto, Thunder Bay, Belleville and Brantford – that zeroes in on child-welfare cases in local youth courts. The program started in 2015 and has prompted policy changes to ease youth bail conditions. It also requires “two-hatter” lawyers and judges who must consider the young person’s child-welfare background alongside any youth criminal charges.

The Cross-Over Youth Project has found not only that kids who live in group homes are disproportionately charged for relatively minor incidents, but they’re sometimes being kept in jail because they have nowhere else to go. That violates the Youth Criminal Justice Act, which specifies criminal courts must not be used for child-welfare matters. And yet, it still happens, says Judy Finlay, the project’s principal investigator and a Ryerson University professor.

She says the biggest problem is that nobody works together.

“It’s not the kids. It’s the system. If the system can work better together on behalf of these kids, then we’ll see better outcomes.”

That’s where the project comes in. It identifies crossover youth case by case at the courthouse. There’s no other way to track them between state-run institutions. The project brings together a team of people including a judge, prosecutors, defence lawyers, social workers, police and a youth co-ordinator so the cases can be handled in a “trauma-informed” way.

“It’s really difficult to get people to work differently at the frontline level,” says Finlay, Ontario’s former child advocate. “Once they do it, it’s really quite impressive and it’s really quite effective.”

Other communities, including Peterborough and Brampton, have followed in the pilot project’s footsteps without government funding, she says.

“I know the federal government really has eyes on this project, and I think they would like to see it go across the country, because it can go across the country. That’s what we’re doing, essentially, is trying to learn on the ground so we can roll out best practice.”

In B.C., where fewer kids are jailed than anywhere else in Canada, the representative for children and youth put out seven recommendations to curb overrepresentation of foster children and Indigenous children in the justice system. Among them was a request for a review of justice department policies to ensure foster kids don’t get charged in situations where other kids wouldn’t. That was in 2009. They’re still working on it, says Bernard Richard, B.C.’s representative for children and youth.

“I’m far from saying that we’ve resolved the issue, but clearly we’ve identified some possible solutions, and we’re advocating strongly for those solutions,” he says.

The office has found kids who grow up in child welfare “are over-represented in every statistic,” Richard says, and it concerns all Canadians.

“Taxpayers are the ones that will bear the cost of not doing anything,” he says.

“You know that once they’re down that path (of criminal behaviour), it often gets irreversible, and the costs are huge in the course of a lifetime. So (it’s about) being able to find the right solutions early on.”

But those who’ve worked in the criminal justice and child welfare systems don’t need statistics to understand that vulnerable teens who grow up in the care of Child and Family Services are often more likely to face criminal charges. They see it happen all the time.

“On a daily basis, we would see how many of our clients who were being referred to us were coming with criminal charges, and we saw that a high percentage of them were children in care,” said Cora Morgan, Manitoba’s First Nations family advocate. “It’s a direct feed.”

She also worked at Onashowewin, where she helped young people resolve their criminal cases through Indigenous traditions.

Morgan and others who spoke to the Free Press — lawyers, former child welfare workers and former youth in care — said it’s more common than the public might expect for teens in foster care to be charged and do jail time for relatively minor offences.

“There are some youth you work with who you can’t help but feel they never really had a chance,” said Josh Mason, a former youth lawyer with Legal Aid Manitoba, who is Métis.

“The underlying problem is not just how we sometimes set up youth for failure to become involved in our (criminal justice) system, but the actual place in which they are being housed can sometimes have negative effects on (them).”

For a teen who’s lived through a traumatic childhood, and sometimes cognitive impairments, a foster home or group home environment can magnify behavioural problems and translate into crime.

Breaking a lamp, tossing couch cushions, punching a hole in the wall and throwing food can all lead to mischief charges.

Throwing a hairbrush during a fight with a foster sister? Assault with a weapon.

Writing an angry letter to an abuser and hiding it under a mattress? Uttering threats.

Cutting yourself with a kitchen knife? Possession of a weapon.

The issue has been on the radar for Manitoba’s children’s advocate for years. The office has pushed for an expanded mandate to include the youth criminal justice system in its advocacy work for children. Legislation supporting the office’s much broader mandate was passed earlier this year but has yet to come into effect.

“I don’t think that many people in Manitoba necessarily are aware that we’re a world-leading jurisdiction in the incarceration of children, and if you look at how racialized it is in terms of the over-representation of Indigenous children in that system, it begs for change,” said Corey LaBerge, Manitoba’s former deputy children’s advocate.

“I think we need to take a public-health approach in terms of looking at why children are occupying these social spaces, why are they living in a world that’s framing their experience as criminal, and why aren’t we creating a world for them where they can be healthier? I think if incarceration was the answer, given our incarceration rates compared with other provincial jurisdictions, you’d think that we’d have lower crime rates, but we don’t.”

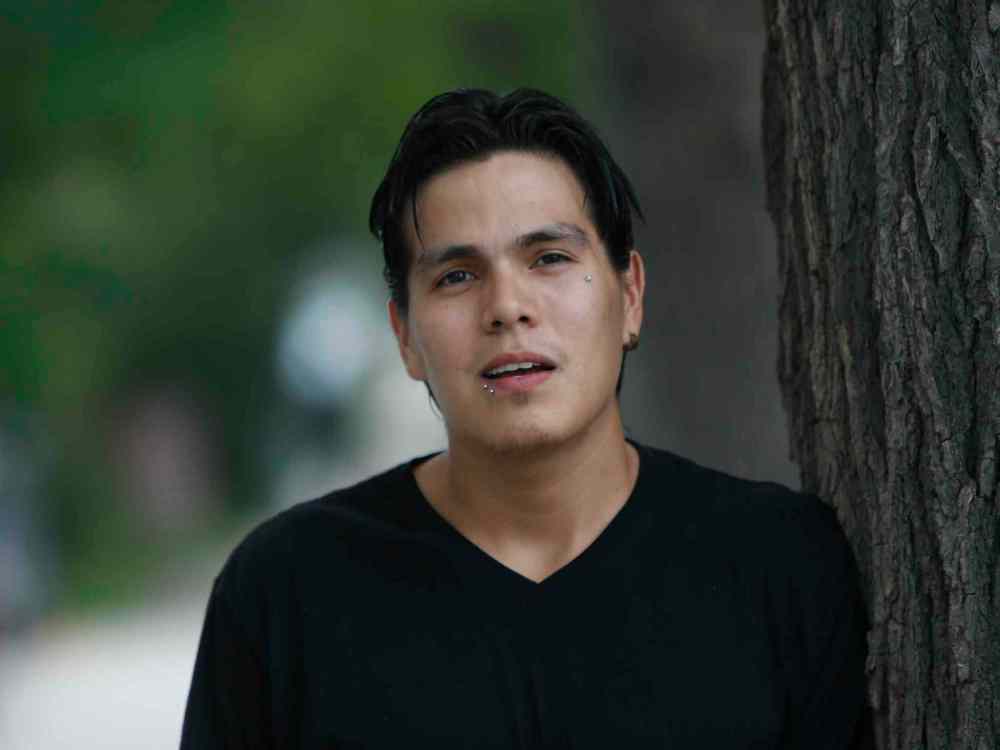

Growing up in foster care, Matthew Shorting often felt as if “every little thing” he did was under scrutiny. By the time he was six, he’d been in 11 foster homes. At 15, he was sent to a group home in the city and found himself brushing up against the law. He spent a night in jail on marijuana trafficking charges when he was 16 and vowed never to return.

“I sat in the youth centre and I was alone. I was like, ‘I cannot do this.’ I did not want to be trapped behind the walls again,” he said, comparing the feeling of being behind bars to being confined in his foster home.

He was convicted and put on probation. He broke curfew once but was given the benefit of the doubt from a group-home worker who decided not to report him. It wasn’t until years later, as a casual staffer at several Winnipeg group homes, that he started to see how many foster kids ended up in jail.

“What I have noticed is that a lot of the different group homes would charge people for assault within the home, like on workers and the staff members. It would be as simple as applying force without consent: someone throwing a pillow at someone, something little like that,” Shorting said.

“I did see people who were not making their conditions and were being held at the youth centre, for sure. I think that the weird thing about that is that sometimes youth who are held in the youth centre and they had charges, it was easier to hold them in there than find them a home sometimes,” he said.

Now, as a restorative justice worker, the 27-year-old knows it can be common for kids who grew up in CFS care to act out against authority figures. If their parents or guardians were abusive or incompetent, “it really skews the way you view authority, and when you go and talk to a probation officer or a police officer and the way they’re trained, it’s a big trigger for youth in care,” Shorting said.

Police decide when to lay criminal charges, and CFS staff is trained to call them when necessary. In places such as Marymound, which runs group homes and foster care treatment units in Winnipeg and Thompson, police are meant to be called for incidents involving violence or “fairly dramatic” property damage, said Ben Van Haute, who was Marymound’s interim CEO when he was interviewed earlier this year.

“In those cases that we call, it would be… a serious enough incident that the police would charge them and would lodge them at the youth centre. Then they’re in the correctional stream at that point in time. Our intent in terms of working with kids who find themselves in that situation is that we’re not abandoning them or giving up on them. It’s a legitimate kind of life experience. Like if you’re walking around and hit somebody in the face, it’s likely somebody’s going to call the police. You can’t be assaulting people and hurting people,” Van Haute said.

“We have kids who come here with some pretty bad life experiences and have some behaviours that they use for coping that are not acceptable in the community. But part of the work that we’re trying to do is provide them with some alternatives,” he said.

“We’re not, essentially, the cause of the issue. We’re hopefully a part of the solution in terms of how we help them turn that corner.”

Van Haute said group-home operators need more funding that’s dedicated to training staff and raising salaries to competitive rates to attract and keep the best employees.

“There’s virtually no money that’s attached to training that we get from government. Any training that we do is from what we can fund from within the money we receive for delivering services to the kids. That’s a major issue for pretty much all operators in Manitoba,” Van Haute said.

More training and education are necessary to keep child-welfare cases out of criminal courts, said NDP MLA Nahanni Fontaine, justice critic for the Opposition.

“I know that people say that quite often. It seems to be kind of the go-to response to this, but (without training), it really does translate into the numbers of children that are criminalized within the system,” she said.

“If you have more understanding of the context of the child that you’re dealing with, then perhaps you’re more likely to divert (into a restorative justice program) and to offer those services and supports instead of those first initial charges. The bottom line is this: when we charge a child, for whatever it is, it begins this long process in and out of the justice system,” Fontaine said.

“The conditions are so strict and so stringent that are placed on you, they’re unattainable, and so then it further entrenches your criminalization.”

The provincial government has promised reforms and said it’s taking a “collaborative approach” to deal with the issue.

“The numbers are striking. That’s why it’s so important we have reform, so we have less children to involve in the (CFS) system and a lot more permanence in terms of (forming) life-long connections so there isn’t as (many) children going into the criminal justice system,” said Families Minister Scott Fielding.

He and Justice Minister Heather Stefanson sat down for a brief interview about the overlap in the child-welfare and criminal-justice systems.

“We know that things need to change. We want to work with Indigenous leadership and the federal government to make those changes to make the system better for kids,” Fielding said.

Asked if concerns about the overlap between the two systems and the effect of administration of justice charges on youth in care will prompt policy changes, Stefanson said the justice department is continuing with its “three-pronged approach” for crime prevention, restorative justice and “responsible reintegration” for young offenders.

“These challenges didn’t come about overnight. It’s been many years of building up to where we are, but we recognize there’s challenges and that’s why we’re taking this very proactive approach and collaborative approach to this,” Stefanson said.

A spokesman for the Winnipeg Police Service said the police department doesn’t track how many calls it receives from group homes or how many criminal charges are laid from such incidents. Those initial charges can spiral into long-term involvement in the justice system for teens who are subsequently charged with violating conditions imposed upon them by police or the courts.

After break-and-enters, the second most common criminal case in Manitoba’s youth court is for failing to comply with an order – one in a series of administration of justice offences that make up 13 per cent of all youth cases annually in the province, compared with 10 per cent of youth cases nationally. In Manitoba in 2016, failing to comply with an order was the most serious charge against about 20 per cent of youth involved in the justice system. That number was less than seven per cent in 1998, Statistics Canada data show.

if(“undefined”==typeof window.datawrapper)window.datawrapper={};window.datawrapper[“uRexx”]={},window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].embedDeltas={“100″:501,”200″:433,”300″:417,”400″:417,”500″:417,”600″:400,”700″:400,”800″:400,”900″:400,”1000”:400},window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].iframe=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-uRexx”),window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].iframe.style.height=window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].embedDeltas[Math.min(1e3,Math.max(100*Math.floor(window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].iframe.offsetWidth/100),100))]+”px”,window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(“undefined”!=typeof a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var b in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])if(“uRexx”==b)window.datawrapper[“uRexx”].iframe.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][b]+”px”});

if(“undefined”==typeof window.datawrapper)window.datawrapper={};window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”]={},window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].embedDeltas={“100″:371,”200″:321,”300″:321,”400″:304,”500″:304,”600″:304,”700″:304,”800″:304,”900″:304,”1000”:304},window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].iframe=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-5mXuc”),window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].iframe.style.height=window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].embedDeltas[Math.min(1e3,Math.max(100*Math.floor(window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].iframe.offsetWidth/100),100))]+”px”,window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(“undefined”!=typeof a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var b in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])if(“5mXuc”==b)window.datawrapper[“5mXuc”].iframe.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][b]+”px”});

if(“undefined”==typeof window.datawrapper)window.datawrapper={};window.datawrapper[“BbouR”]={},window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].embedDeltas={“100″:693,”200″:455,”300″:370,”400″:336,”500″:302,”600″:302,”700″:285,”800″:285,”900″:268,”1000”:268},window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].iframe=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-BbouR”),window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].iframe.style.height=window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].embedDeltas[Math.min(1e3,Math.max(100*Math.floor(window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].iframe.offsetWidth/100),100))]+”px”,window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(“undefined”!=typeof a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var b in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])if(“BbouR”==b)window.datawrapper[“BbouR”].iframe.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][b]+”px”});

Caseload data from Legal Aid Manitoba suggests kids in CFS care disproportionately face administration of justice charges. Forty-six per cent of legal aid cases involving youth in care are administration of justice charges, compared with 34 per cent for children who aren’t in CFS care.

Foster kids’ cases make up 25 per cent of the total youth cases handled by Legal Aid. The actual number of CFS-related cases could be higher, since some case files may not specifically indicate a youth is in care. The proportion of kids in child welfare in Manitoba, meanwhile, is estimated at about three per cent of the province’s youth population. Upwards of 90 per cent of kids in Manitoba’s child-welfare system are Indigenous.

Police in Manitoba can use their own discretion when deciding whether to lay charges, and not every criminal charge has to be approved by the Crown prosecution office before it is laid, unlike pre-charge screening systems that exist in some other provinces, including B.C., Quebec and New Brunswick.

“I’ve seen situations where police have released young people and put them on conditions that are really not warranted or reasonable,” Manitoba Legal Aid defence lawyer Sandra Bracken said.

Crime created by the courts?

As violent crime declines across Canada, steady rates of charges for breaching court-ordered conditions are prompting concern about what one researcher calls court-created youth crime.

As violent crime declines across Canada, steady rates of charges for breaching court-ordered conditions are prompting concern about what one researcher calls court-created youth crime.

Jane Sprott, a professor of criminology at Ryerson University, has been studying the spread of administration of justice offences for close to a decade. She’s found no evidence that multiple strict bail conditions improve public safety. Instead, she says, the more conditions a youth has to follow, and the longer they’re ordered to follow them, the more likely they are to break them and wind up with new charges.

“The courts are creating these things themselves,” Sprott said.

“I don’t know how people think they’re just going to charge and arrest and convict and imprison their way out of this problem. We’ve created it, because if you didn’t put the condition on in the first place, it wouldn’t have been a problem,” she added.

“We have to think about how we want to use a really expensive resource like court and custody, and we need to think carefully about conditions we place on people.”

When Andrew Swan was justice minister under the former NDP government, Crown prosecutors were trying to tailor the laundry list of standard conditions to make sure they made sense for the individual, he said.

A Manitoba Justice spokeswoman said there haven’t been any recent policy changes regarding the court conditions that are imposed on youth. Neither has there been any studies on the issue. Swan said he was aware during his time as minister that the policies at some group homes meant kids who lived there faced criminal charges for incidents that kids who lived with their families typically wouldn’t.

“I think it was just accepted. I mean, we need people to work in group homes, and they need to know that they’re protected. So no, we didn’t try to change that process,” Swan said.

“If you’re a teacher or you’re a group home worker or an ordinary citizen who gets assaulted or something stolen, I think it’d be a tough sell to say that this wasn’t criminal behaviour. If you’re talking about the breaches, yes, there can be complications for youth if they fail to follow the conditions that have been set,” Swan said, making the point that breach charges are important for public safety and could be drastically reduced if more youth were held in custody longer.

“If it’s a youth who’s given a condition that’s difficult because of their own limitations or an addiction or something else, that can be problematic, because then you’re not really getting at the root of the problem. You’re just rearresting the youth for falling back into their addiction or their mental-health issue, whatever it may be.”

“Sometimes, it seems like to mitigate a young person’s risk – and the risk is really caused by the fact that they’re a young person with a history of trauma who’s in care – we sometimes add extra conditions or extra layers of supervision to make up for the fact that the young person doesn’t otherwise have that available to them.”

The fear that something awful might happen to a child under her care was ever-present during Rosie O’Connor’s career as a child-welfare worker.

“It’s the demon that sleeps at the foot of my bed every night,” she said, now retired after about 20 years as a Child and Family Services employee and another 10 spent in the children’s advocate office.

The case of Phoenix Sinclair serves as a warning to those working in the system. The child was apprehended by CFS when she was born in 2000. Her mother and stepfather were later given the chance to parent her, and they killed her when she was just five. A public inquiry in 2012 exposed problems in the system, including a lack of oversight by her care worker.

In the aftermath of the Phoenix Sinclair Inquiry, O’Connor said many child-welfare workers are quick to call police about minor incidents because they are afraid something tragic could happen.

“When we’re looking at risk around kids in care, sometimes we’re looking way too much at the risk to ourselves rather than the risk to the child,” she said, noting kids who run from their CFS placements are often labelled “high risk,” which can lead them to longer stints in jail when they’re found and start them on a path toward more serious criminal behaviour.

“I think it’s out of fear that ‘Oh my God, something could happen to them’ — but without the recognition that the intervention sometimes is much more traumatic than what it is that you’re attempting to protect them from.”

O’Connor recalled the case of a girl, who has since aged out of foster care and would be in her 20s now, first charged with public intoxication at age 12. She would drink, run from her CFS placement and was sexually exploited. At the time, care workers believed she needed to be “kept safe” in jail, O’Connor said.

“She spent more than two-thirds of her adolescence in the youth centre after breaching court orders. So kids who were found guilty of armed robbery or (other serious offences) did less time than she did,” she said.

“I’ve seen kids at the beginning of their time in care and on the run and in this kind of spiral down into the youth centre and into incarceration. They went in, and they come out with scars all over their arms because they’re in pain.”

To move beyond the fear and help kids heal, O’Connor is a big believer in youth mentorships and independent-living programs that teach teens how to live on their own and set them up with their own apartments, giving them a place to belong.

“You need to be taking fewer kids into care in the first place, but you certainly need to have places if they are in care where they have a place to belong,” she said.

“The key to any kid’s healing is not me as a worker or an advocate or a lawyer or a psychiatrist, it’s the family. It’s about having a place to belong.”

“Let me out!” the teen calls from within the prisoner’s box, holding up her hands with false bravado, when it’s her turn to appear before the youth court judge.

Despite her posturing, she already knows she won’t get out this time.

Now approaching her 18th birthday, she’s been in and out of jail repeatedly. The list of breach charges grows each time she breaks curfew and must return to court. In the past year, she’s gone missing from her group home; she’s reported and recanted sexual assault allegations when picked up by police, who warned her about the danger of making a false statement; and she’s been held in observation for behavioural and mental-health concerns.

This fall, the Crown dropped some of the breach charges because the teen showed up a little over an hour late after calling her group-home worker from a cab, saying she was on the way. At the time, Crown and defence lawyers took another look at the curfew conditions that were consistently tripping her up. Together, they worked with her probation officer to relax her curfew.

She was less than three weeks away from the end of her probation order – set to expire before another curfew breach would automatically land her in the adult criminal justice system – when she was arrested for the first criminal offence not tied to the group home: armed robbery.

In December, she pleaded guilty to carrying a friend’s baseball bat into a 7-Eleven and demanding cash and cigarettes.

A new year will begin, and she’ll speak to another probation officer, who will ask questions about what happened, whether she’s sorry, and how she ended up here.

For now, she says goodbye to the Crown and defence lawyers handling her case. Adopting a friendly tone, she calls them by their first names before she heads back to custody.

“Have a good day, you guys,” she says.

And they wish her the same.

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, December 31, 2017 11:48 AM CST: Adds third data chart, changes thumbnail