Pumped dry

Tight margins, volatile pricing makes it tough for smaller gas stations to keep the fuel flowing

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/05/2016 (3583 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

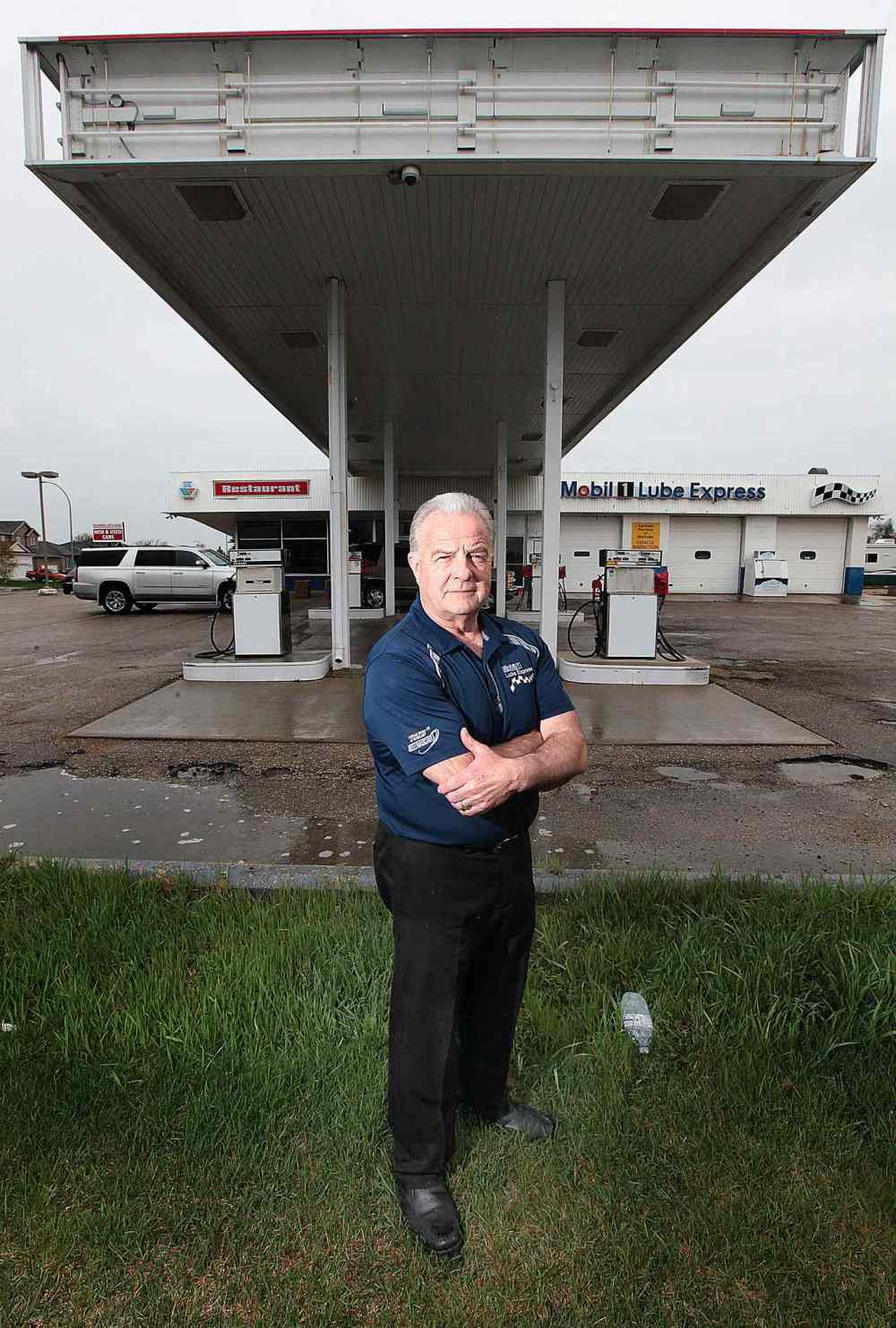

In almost every respect, Jeff Kendel is still running the typical corner service station.

There are three service bays, six gas pumps and a diesel pump, an air compressor and windshield washer fluid, coolant and oil products for sale. Customers know it’s a place where even small repair jobs — a burned-out headlight bulb, a blown fuse — are still welcome.

“Come back first thing in the morning. If you can make Pete smile at 7 a.m., I’ll buy you breakfast,” Kendel joked to a customer who was moments too late for a quick battery-cable repair, referring to his mechanic, who had just left for the day.

“Make the repair free,” the customer fired right back. “I’m a Mennonite, remember.”

Down the hall, you can still get a Howie dog, named after Jeff’s late father and former business partner, and a Verna burger, named after his late mother, who ran the restaurant.

Hit him at the right time, and you can get the city’s best-tasting oil change, thanks to a restaurant gift certificate frequently included with that service.

What you can’t get, however, is fuel.

Jeff’s father, Howard, got into the gasoline business in 1959, taking over a service station on Kimberly Avenue in East Kildonan.

A few years later, not far away, an Esso station at the corner of McLeod Avenue and Highway 59 would begin a slow decline. The owners, who built in 1964, failed to anticipate the arrival of a new Highway 59 in the late 1960s, just a half-kilometre to the east. The beach-bound traffic it needed was no longer passing by.

The gas station with one service bay and a restaurant closed in 1972, according to Kendel. He and his dad came along two years later. What killed the old station didn’t worry them, he said.

“My dad was the world’s best mechanic,” Jeff said. “If it was broken, he could fix it. If he didn’t have the part, he’d fix it anyway. He could fix anything.

“He knew he had a loyal following, and they would follow him anywhere.”

And they did. Two years later, Kendel’s Service Station at 1157 McLeod Ave. added two service bays. Life, and business, was good. “Things were humming,” he said, adding one year, they sold four million litres of fuel. “That was a lot.”

As the years went on, there was money to be made selling gas. Prices were stable, and you could count on about a 10-cent profit on each litre of fuel. If you ordered it Monday at one wholesale cost, it was about the same wholesale cost, plus taxes, when it arrived, and the street price never moved much from 10 cents above that.

Gas was flowing, breakfasts were sizzling and the service bays were hopping. It was everything Jeff and Howard had hoped it would be.

Jobs were plenty, for family, for mechanics, for gas jockeys.

Money from oil companies was flowing as quickly as the gas. Needed new pumps? Done. New canopy? Easy. Signs, promotions and personal service from local oil-company representatives were as reliable as sunrise.

Then it started to change.

“In the last year of my contract with Shell, I asked them for two gallons of white paint to touch up the canopy. Two gallons of paint! ‘Not in the budget,’ was the reply,” Kendel said.

That personal service? Gone. Kendel was forced to phone some call centre, “God only knows where,” only to have the same local guy — whose number Kendel knew — call back.

‘These kinds of practices would land people in court in the U.S’

Dan McTeague knows Kendel’s plight. He said he saw this coming in 1998, when as a Liberal MP, he was chairman of a committee that wrote a report warning anti-competitive practices were beginning to appear by the oil companies. Consolidation of refineries was putting the squeeze on competition, and it became something the oil companies could use to put the screws on independents.

“These kinds of practices would land people in court in the U.S.,” McTeague, now the senior petroleum analyst for GasBuddy.com, said.

He is not the least bit impressed by the government’s Competition Bureau. “The office of monopoly preservation,” he said snidely. Unlike in the U.S., where the burden of proof is at a civil level, in Canada, prosecution is at the criminal level. “It is this high test in Canada that makes anti-competitive behaviour tough to prove, much less stop or deter.”

McTeague said a systematic reduction in the number of independent gasoline retailers has led to higher prices, reduced competition and greater volatility in prices. One of the biggest culprits, according to his 1998 report, was the federal government.

“The creation by the federal government of Crown-owned Petro-Canada was partly devised to enable Canada to move toward oil self-sufficiency…” said the Report of the Liberal Committee on Gasoline Pricing in Canada. “However, establishing Petro-Canada, as a so-called ‘window to the industry’ and an instrument of public policy, contributed to a sharp reduction in the number of refiners and marketers in Canada.

“Petro-Canada’s birth brought about the removal of Petrofina, British Petroleum, Gulf, Pacific Petroleum and Cities Service from the Canadian oil industry.”

The inevitable result was foreseen in his report: today, there are only three national suppliers of petroleum products, Shell Canada, Suncor, which now owns Petro-Canada, and Imperial Oil. In Western Canada, you can add Husky to the mix. If you’re wondering how competitive they are with each other, consider that all the trucks for Winnipeg stations, regardless of brand, drink from the same pipeline.

“On any given day, a truck will pull into a terminal, load up with gas and then pull away to another point to put in the branded additives,” McTeague said. “It’s all the same gas.”

During a phone interview, McTeague is accessing Winnipeg’s “terminal rack rate,” the industry term for that day’s spot wholesale price for clear gas, on his laptop.

“In Winnipeg today, Shell is 52.4 cents per litre. Suncor is — imagine that! — 52.4 cents per litre… and Imperial is — oh, wow!, a whole tenth of a cent! — 52.3 cents,” he said, feigning surprise.

Contrast that with Grand Forks, N.D., where the wholesale price on the same day ranged from 122.42 cents per gallon to 128.50 cents, from six different suppliers, some of whom have no vested interest in who they sell gas to.

What it means, he said, is that in Canada, after taxes, “the only illusion of competition is for the last eight or nine cents per litre.” His report suggested retailers’ hands are tied.

“In the past, price competition at the pump came mainly from unbranded independent retailers. With the decline in the number of refiners and what some see as a concentration of power and lack of active competition at the wholesale level, independents no longer have the ability to deviate from what many of them view as a mandated price structure,” the report said.

Pointing to Ontario, where the committee identified 17 companies that left the business from 1990 to 1998, the report painted a grim picture of the Toronto market.

“Retail margins in Toronto and surrounding areas frequently reach zero, and at times, can go into negative figures,” the report found. “Since this is the only margin available to independents, the choice is simple: either lose money or lose market share. In either case, their ability to remain financially solvent is challenging.”

McTeague said today, “In Toronto, the independents have been wiped off the map, and those that remain are free to charge 10-cents-per-litre margin.”

Those so-called price inversions, where you charge unfavourable clients more at wholesale than your favoured clients can sell retail, are clearly outlawed in the United States, he said.

Independent economist Robyn Allan, who has studied gasoline prices, attributed much of the high wholesale margins to the high cost of extracting oilsands bitumen.

“My work in this area has stemmed from a concern that the excessive pricing is robbing our economy of much-needed stimulus and forcing individual consumers to subsidize — prop up — overly aggressive investment decisions by large multinationals in the oilsands,” she said in an email.

“What all the refiners are doing is relying on past high oil prices, and the pump prices these generated, to enable excessive profits. Pump prices should be much lower than they are if the industry were responsive to production costs.”

The future of the oilsands industry is, of course, shrouded in smoke: the impact from the fire burning out of control near Fort McMurray, Alta., the oilsands capital, won’t be known until long after the flames are out.

High margins have caught the attention of no less an august source than the Bank of Canada, which raised the alarm in January about Canadian gasoline prices bearing little resemblance to the tumbling price of oil.

“Although gasoline prices have declined, they have not fallen as much as the reduction in crude oil prices would suggest, based on historical experience,” the bank’s Monetary Policy Report said.

The birth of Domo

Douglas Everett was a young lad washing cars for his family’s Dominion Motors — at the time, Canada’s largest Ford dealer — when Winnipeg’s largest independent gas retailer was born.

The year was 1958, and Dominion Motors had two sets of pumps, both primarily to fill cars for the dealership but also with some retail business: one was at the Fort Street and Graham Avenue dealership, one was at the truck outfit where the Dominion Centre stands today. In 1970, Everett’s father, a future senator also named Douglas, got the idea to approach Canada Safeway about setting up small gas “kiosks” at the streetside ends of the stores’ parking lots.

“The idea was these spots weren’t being used, or if they were, it was the pirate parkers, who would park there and go somewhere else,” the younger Douglas Everett said. “So the rent was very inexpensive.”

Of course, at the time, Safeway’s largest competitor in the grocery business was Dominion Stores, “so they didn’t want a Dominion Gas in their parking lot,” Everett said with a chuckle. Take the Do from Dominion and the Mo from Motors, and Domo was born.

The kiosks were originally designed to look like miniature versions of the Safeway store behind. “The kiosks were very simple, just a small building and two pumps, and Safeway agreed to three locations in Winnipeg and that’s where it all started out.”

Today, Domo operates 80 retail outlets from Winnipeg to Vancouver and wholesales gas to 45 independent dealers who fly the Domo flag. The younger Everett is the president.

He agrees it’s a tough business, even with 125 outlets. He said around 1990, consolidation in the industry slashed the number of gasoline retailers in Canada to 12,000 from about 25,000.

At that point, margins started to get squeezed to the point volume was key. “And then the big-boxes came in, and they were using them primarily to get customers into the stores, so they weren’t so concerned with profit.”

Everett agreed there is little competition at the wholesale level.

“There are only two places to get gas in Winnipeg. It all comes down one pipeline and it splits off at Gretna, and some goes to the Esso rack on Henderson and some goes to the old Shell refinery on Panet Road,” he said. “Definitely, it’s all the same gas, and when you go to the rack, it’s not like ‘Oh, there’s Shell’s gas over there, there’s Esso’s, there’s Domo’s…’ you go in and fill up at the same rack.”

Everett said “what makes Domo tick” are tight cost controls and lots of volume. “The margins are very, very thin, so you need a lot of volume to be profitable.” The company also benefits from high-traffic, convenient locations and brand familiarity driven by the slogan “Jump to the pump,” and the bouncy kangaroo that drives home the point.

Domo’s volume allows it to negotiate a discount from the wholesale price for gas, which helps the retail margin some — and that discount is the company’s profit when selling to independent Domo dealers, who keep the retail margin. And while the agreement with Safeway meant those early stores sold fuel and oil and nothing else, today’s Domo locations sell chips, pop and other sundry items.

Those, Everett said, are the only items “where you can get 30 per cent margin, which you can’t get anywhere close to on gas.”

Squeezed out by fees

The pumps are still there. The canopy still shields them from the sun and the rain. The odd customer still pulls up, expecting a fill. But the power is off, the tanks are dry. Plastic bags are taped over the nozzles.

Kendel said for smaller outlets such as his used to be, profits on gas are so small, they’re wiped out by credit-card charges.

“If a guy buys $100 in gas — and who has $100 cash? — he pays by a credit card,” Kendel said. “He thinks he’s my best customer, but I haven’t made a cent.”

Add in the fees for Air Miles, when his was a Shell outlet, or Aeroplan, when his was an Esso station, and he was losing money on most of his sales. Without a high-volume convenience store or car wash, it stopped making sense to sell gas.

That increased volatility McTeague’s report noted? A killer to a small outfit such as Kendel’s. Kendel said he would often order gas at one price, only to see the street price fall, sometimes to below his wholesale price. As well, his price was fixed at the time of ordering, not at delivery.

Today, by and large, the only companies making money selling fuel are the oil companies. At the retail level, fuel is primarily a loss-leader. Or at corporate stores, the retail margin is added to the wholesale margin for as much as 28 cents profit on each litre sold.

For some stores, that’s OK. The gas is the draw, without which there are no car washes or corn chips to sell. “If the guy can sell you a car wash, that’s when he’s really making money,” Kendel said.

At the most successful retail chain in these parts — Co-Op — retailers do not participate in the revenues from selling fuel at all. They merely hire the attendants and are reimbursed for the attendants’ wages. Virtually all the money they make is in the pop, lottery tickets, chocolate bars and car washes people happen to buy while fuelling up.

Co-Op has managed to earn a large share of the market, thanks in part to what Allan calls “returning the excessive margin to customers in the form of a rebate.”

Kendel went from the red, white and yellow of Shell to the blue and white of Esso before finally hanging up the nozzle in 2015 for the last time.

Today, it’s good again at Kendel’s. He’s not selling gas, but the restaurant and service bays churn out a good bit of revenue. Many of those early customers, who remember Howard and Verna, still pop in for the Early Morning Breakfast, which is served all day long, or the homemade split-pea, minestrone or cabbage soups du jour. A cul-du-sac in Harbourview South — Howard Kendel Place — is named after the late mechanic.

“Things are really good. I mean, it was only the service and the restaurant making money anyway.”

But he says the changes that have been brought to the retail gas industry have robbed Canadians of a small part of their cultural fabric. The corner service stations provided a valuable service: they were often full-service, with attendants who would fill tanks, clean windshields, check oil and even park the car, if the customer was heading into the restaurant.

With a stable staff, a service station became a part of the neighbourhood, and the interactions became a part of everybody’s social life. Today, you can pull up to a 20-pump self-serve, fill the car, pay for it and clean the windows yourself and never even have to say ‘Hi’ to another human being.

How did we get here?

Timing has a lot to do with it. McTeague said he was raising these issues as a Liberal MP while the governing Liberals were still smarting from Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Policy, which instituted double taxation on petroleum products, inflamed tensions in the West, sparked threats of an Alberta secession and led to the infamous quote in protest: “Let the eastern bastards freeze in the dark!”

McTeague’s proposed changes to the act weren’t limited to the gas sector, so the Canadian business lobby also railed at the amendments, and with the two issues combined, the Liberals didn’t have the stomach for a fight at the time.

“I wish people had listened to me when we still had time to fix this,” McTeague said.

Kendel attributes part of the national indifference to typical Canadian values.

“We’re too polite. We figure we can still buy it, so we won’t make any waves.”

But also, McTeague said, the fear was Canada needed its institutions to muscle up to compete internationally, so competitiveness within Canada was ignored. He is no fan of Canada’s Competition Act.

“We have some people beating their chests, proclaiming it a great piece of legislation,” he said. “Frankly, it does not work.”

In the U.S., competition is valued so much, courts award triple damages in antitrust cases, which can also result in US$100-million fines and, rarely, jail time. So an independent operator in Grand Forks, assuming he’s not bound by a contract, can fill his station’s tanks with fuel from any of the area’s six suppliers, who not only have varying wholesale prices but can also offer volume discounts and favourable payment terms to lure new business.

In fact, McTeague said some wholesalers, fearful of antitrust violations, will often deliberately offer slightly better terms to independents. Many also do not operate their own retail chains.

Domo’s Everett said because the retail margins are so thin, competition even by independents is tough. He could cut his price, “but then the majors would just match it, and I’ll run out of money a lot sooner than they will.” Plus, he still has to buy the gas from the major operators.

Instead, Domo offers discounts, particularly on what it calls “rollback Tuesdays and Thursdays,” where the pump price stays the same, but a five-cent-per-litre discount is calculated on each sale.

What does the oil industry have to say? Who knows?

Trying to reach an oil-industry contact for comment was like a dog chasing its tail. Suncor and Shell both referred questions to the Canadian Fuels Association. The Canadian Fuels Association referred questions to research firm Kent Group Ltd. Kent Group said it couldn’t speak on behalf of the industry and referred questions back to the Canadian Fuels Association, whose chief spokesman, Bill Simpkins, was away. A week later, when Simpkins returned, he appeared ready to give an interview, asking for the author’s phone number, but when supplied with a number, referred questions to the CFA’s Western Canada spokesman Brian Ahearn. He was also “away.”

A final request to the president of the CFA was not returned.

kelly.taylor@freepress.mb.ca

Kelly Taylor

Copy Editor, Autos Reporter

Kelly Taylor is a copy editor and award-winning automotive journalist, and he writes the Free Press‘s Business Weekly newsletter. Kelly got his start in journalism in 1988 at the Winnipeg Sun, straight out of the creative communications program at RRC Polytech (then Red River Community College). A detour to the Brandon Sun for eight months led to the Winnipeg Free Press in 1989. Read more about Kelly.

Every piece of reporting Kelly produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.