Treaty No. 1 document can’t convey full story

Series of columns will share the unvarnished truth from the First Nations perspective

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/06/2021 (1711 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

They travelled many miles in the blazing heat of a Manitoba summer in 1871. More than a thousand people strong — on foot, on horseback and by cart. Chiefs, tribe leaders and their families came from all directions. Their destination: the stone fort we now know as Lower Fort Garry.

Their mission was serious — to avoid further bloodshed by negotiating a friendship treaty with the British Crown, in the hope of a peaceful co-existence between the Queen and the people who had lived on these lands since time immemorial, the Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree Peoples.

The legion of First Nations set up camp outside the walls of Lower Fort Garry in the traditional style of tipis and prepared for what would become eight tense and gruelling days of negotiations, ceremonies, disagreements and the kinds of struggles we might expect even today — language barriers, significant differences in culture and customs, and above all, very different intentions and motivations.

This was not a chance meeting. Tensions had been building for years, with violent skirmishes and the Red River Rebellion ending in executions and a reign of terror, as newcomers aggressively pushed their way into Manitoba in pursuit of farmland, laying claim to land they did not own and to which the colonial government was not entitled.

The matter of Aboriginal land title had been established more than 100 years earlier by the issuance of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, by King George III. This agreement not only proclaimed First Nations ownership of the land in North America but laid out legal rules for Crown access to the land that included public negotiations, annuities, and the signing of treaties.

For thousands of years, First Nations have negotiated treaties throughout North America — treaties regarding rights of passage through territory, forging of military alliances, access to hunting or gathering areas, of trade and commerce, as well as neutrality agreements to prevent war and unnecessary conflict.

When it came to the making of Treaty No. 1 as the first of the numbered treaties, First Nations leadership used their negotiating acumen, customary trade practices and significant experience to ensure not only the continuation but the strengthening of their land title, as well as familial and collective benefits, and the long-term protection of their sovereignty and right to self-determination.

“First Nations people had what historians refer to as a full backpack of legal traditions surrounding treaty negotiations,” said former treaty commissioner Dennis Whitebird. “Canada, on the other hand, had its own backpack with its own legal traditions and showed up to the table a motivated negotiator.”

Colonial forces had a lot at stake if prime minister John A. Macdonald was to realize his vision of building a coast-to-coast country complete with an “iron link” to create profitable trade. But he could not achieve the unachievable unless he got “legal” access to the land.

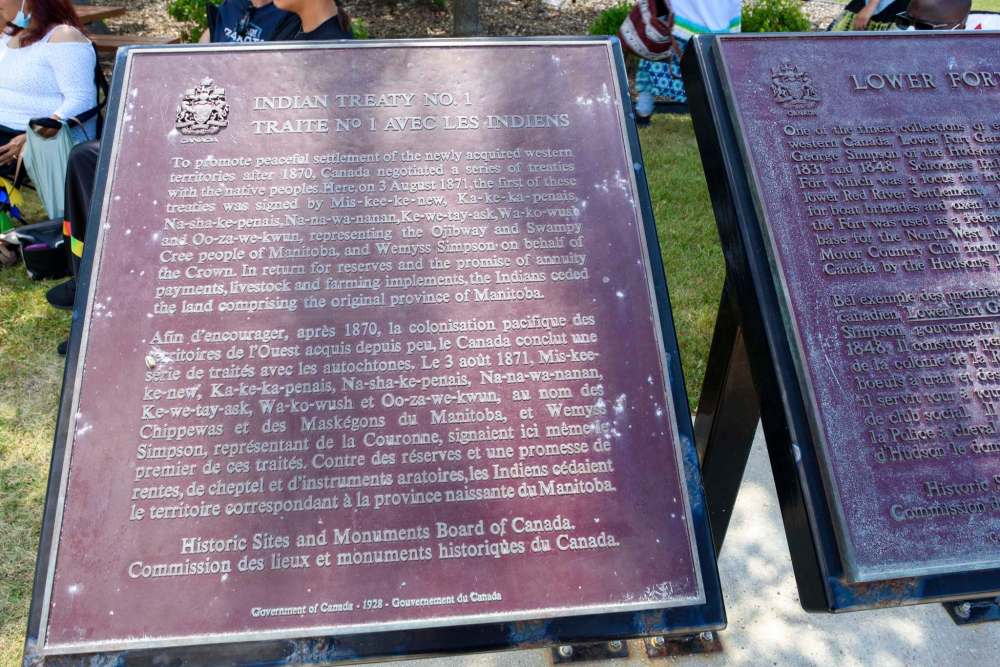

The four-page Treaty No. 1 document that emerged tells only part of this complex and terribly misunderstood story. Over the months of dialogue that led up to Aug. 3, there were many promises, commitments and deals made, some of which were included in an annex that was “lost” as it made its way through the Privy Council approval process. Whether this was an oversight or not, it sent a clear signal to the First Nations that they had rapidly moved into a period when promises made quickly became promises broken.

In the coming weeks, as the Treaty One Nation counts down to the 150th anniversary of the making of Treaty No. 1, this special series of columns will share the unvarnished truth, from the First Nations perspective, and the very real stories of the human beings who worked relentlessly to try to forge an agreement and treaty relationship intended to last “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the rivers flow.”

To First Nations peoples, Aug. 3, 1871, is a date far more significant than July 1, 1867, when colonial Canada became a Confederation. In the coming weeks, let’s take the opportunity to increase our understanding of Treaty No. 1, because the more we learn, the better we can chart a path forward toward reconciliation that offers prosperity and harmony for all, as was intended 150 years ago.

Long Plain Chief Dennis Meeches is the chair and spokesman of the Treaty One Nation Governing Council, which comprises the seven Treaty One First Nations including Brokenhead Ojibway, Fisher River, Long Plain, Sagkeeng, Peguis, Roseau River Anishinaabe, Sandy Bay and Swan Lake First Nations.