Dealing with ‘so much death’ carries personal, professional toll

ICU nurses carry immense burden amidst COVID-19 pandemic

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/03/2021 (1813 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

After a year spent trying to keep the sickest COVID-19 patients alive, a lump still forms in her throat at the thought of anyone dying alone.

In final moments, when she is the only one who can get close, the intensive care nurse has rested one of her gloved hands on the patient’s shoulder. In her other hand, she holds out an iPad.

She and other nurses are used to being the only ones at the bedside with critically ill Manitobans. But in the COVID-19 pandemic, they have another screen to monitor for virtual family visits and last rites.

“Which can be an incredible responsibility to feel,” said the experienced ICU nurse.

She is one of two nurses in the unit who spoke to the Free Press about what it means to care for people and cope with deaths, while carrying an unprecedented workload to monitor surges of other extremely ill patients.

On top of their usual duties, ICU nurses are sometimes the only link between desperately ill patients and their families.

They answer phone calls from anxious relatives, while attending to the life-support machines. They try to comb patients’ hair and give them a fresh shave, so they look their best for video calls with loved ones. But the realities of working during a pandemic have meant nurses sometimes have to set up the iPad and leave the bedside, rushing off to check on other patients who need to be constantly monitored.

The nurses who spoke to the Free Press agreed to be interviewed only on the condition of anonymity, fearing for their jobs.

All of their work is meant to help patients recover, but in dealing with the absolute sickest, they have seen a lot of death.

At the height of the pandemic’s second wave, often only 30 minutes elapsed between one patient dying and another occupying the empty bed — usually just the time it takes to remove the body and clean the room. Or they have to leave the body to someone else and admit another patient in a different area immediately.

There is no time to grieve.

“That is heartbreaking, when you don’t have the time to put in to someone who’s dying,” the nurse said. “For me, that’s more horrific to go home with.”

Especially when, she said, the pride of being able to offer comfort and dignity to a dying patient is all she has to hang on to.

“Many of us can say, over the years, we’ve been the only one at the end, holding that patient’s hand. But we go home with the sense that we did the best that we could do. We can’t change circumstances, there’s lots of things we can’t do, but if it comes down to a hand hold at the end, that person deserves that.”

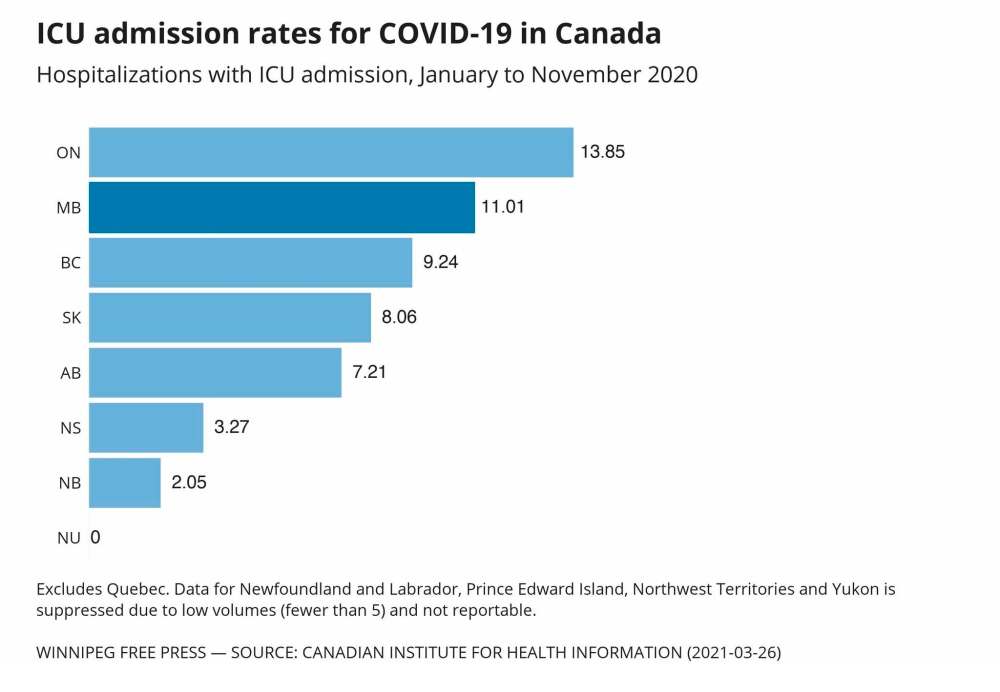

The burden on Manitoba’s intensive care system was immense in the fall, new data underscores.

Manitoba’s per capita rate of COVID-19 ICU hospitalizations was one of the highest in the country (second to Ontario) between November 2020 and January 2021, according to data released this week by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Not all provinces and territories provided hospitalization data, but it showed Manitobans admitted to the ICU died at a higher rate — about 40 per cent — than anywhere else in the country during that period.

At the height of the pandemic’s second wave in Manitoba, overflowing intensive care units meant the specially trained nurses who work in critical care have shouldered double or triple their typical duties.

They have had to learn on the fly about the new virus and the best ways to care for people on ventilators, while being isolated — literally and figuratively — from family and friends for fear of bringing COVID-19 into their own homes.

Even after she received both doses of vaccine, one nurse says she still experiences stigma from those in her personal life who worry she could be a carrier.

The personal toll can’t be overlooked, said retired ICU nurse Alice Dyna, a longtime critical care program educator.

“Just because you take somebody off a ventilator doesn’t mean you close the door and let them go, and now especially with COVID when their family isn’t allowed, that takes a big, big toll on the nurses,” she said.

Typically, patients who end up in intensive care need some kind of specialized equipment to keep them alive.

The nurses who work in the unit are trained to know how that equipment works and how to monitor patients — who usually can’t speak up for themselves — for any signs of distress. Even subtle changes can signal serious problems, and conditions can change in seconds.

The nurses work in 12-hour shifts and have to complete full-body assessments of patients, administer medications, participate in multidisciplinary rounds, keep constant watch for any changes, and document all of their work. They say it hasn’t been possible to keep up with everything amidst the pandemic, when they’re assigned to multiple patients at a time. They say patients tend to do better when loved ones are involved, so they try to keep the families in the loop, but it hasn’t been easy.

“People are stressed, incredibly stressed, maybe the worst stress they’ve ever experienced with their loved one being in hospital and they can’t set eyes on them,” one nurse said.

“Maybe they can’t get the information they need or they’re not understanding, and now you’ve put them off three times because you’ve been in the (ICU) cube with doors closed, in all your PPE, and haven’t been able to get to the phone.”

Others who were brought into the ICU as extenders to keep the unit staffed during the surge were traumatized, another nurse said.

“People weren’t used to so much death, and I haven’t been that person in a long time, so I felt really bad because I kind of forgot that you can be a person who isn’t used to seeing people die. It was really sad for the extenders.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.