Thunderclaps of heartbreak

Grief, tears overcome families at inquiry -- but light of love and hope peeking through

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/10/2017 (2978 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Indigenous women’s lives are stolen in Manitoba, they are taken from all over: their home, someone else’s home, the sidewalk, a park. Some are stolen from a place only the person who took their life knows for sure.

Some vanish, and are never found. Others are recovered from the bush or the river or a patch of lonely ground. So many have been taken, now they have their own term: missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Their memory, though, that never goes missing. They all have someone who holds tight, and hangs on.

So this week, the memories of the lost are carried here, to the heart of Winnipeg. They are raised to the 11th floor of the Radisson hotel, and into a bright ballroom brocaded by inoffensive neutral-tone carpet and crystal chandeliers.

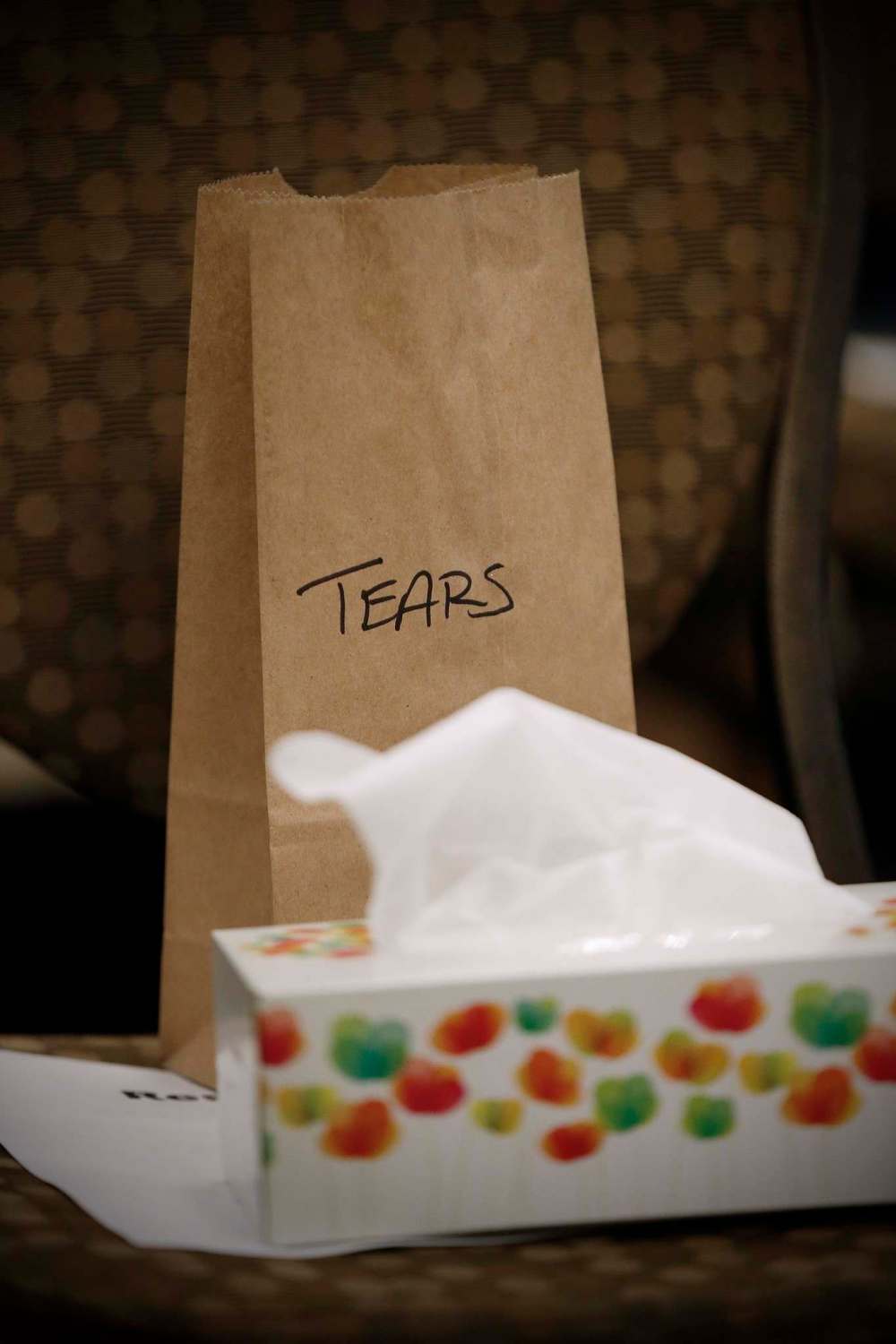

At one end of the room, a qulliq — a traditional Inuit oil lamp — glows with a gentle low flame. The air is spiced by the slight waft of sage. On the chairs are boxes of tissues and brown paper bags labelled, in black marker, “Tears.”

The paper bags, the ballroom, the very reason people are here: all of it is a receptacle for tears. All of it is a basin, waiting to receive the oceans of grief and frustration, oceans that have rolled tides through Manitoba over dozens of years.

It is here the National Inquiry for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls set up this week, for five days of public hearings and workshops in Winnipeg. So far, more than 75 people have registered to give their testimony.

That number is but a fraction of those who have lost someone to violence on this territory. When family members of murdered women cried into the microphone Monday, the first day of proceedings, their tears spoke for too many.

As these brave families relive their grief, in public, let their tears chart a course to the right questions. What will we see in these tears, that we have not already? What more is there to learn, from the things these families know?

From the beginning, the inquiry itself has beleaguered by resignations, deadline pressures and questions over its approach. Skeptics are concerned it will be ineffective; many Indigenous advocates have called for a full reset.

Much of the debate is fair criticism, and in many cases accurate and deserved. Yet the heart of the inquiry isn’t process or procedures; at its core is real pain suffered by real people, and they are the ones speaking out.

So for now, while the families of the lost are speaking, we ought to listen.

On Monday, the inquiry heard a thunderclap of heartbreak and love and frustration. It heard the cry of families rocked by violence and — in some cases — official indifference. It heard of dark holes women’s whole lives fell through.

In the afternoon, Lorna Sinclair remembered how, after her sister, Myrna Letandre, abruptly stopped calling family in October 2006, she called police. She begged them to search the Lorne Avenue house where Letandre lived.

Sinclair wanted police to confront Letandre’s then-partner, Traigo Andretti. Sinclair eventually confronted him herself; he told her he didn’t know where Letandre was, only she’d left suddenly for British Columbia or Calgary.

“I said, ‘I know you are lying,’” Sinclair recalled Monday, but for years police found no trace of her sister.

In 2013, Andretti — then living in B.C. — murdered his wife, Jennifer McPherson. Sparked by that investigation, police soon discovered Letandre’s remains in the Lorne Avenue house. She’d waited nearly seven years to be found.

Sinclair told the inquiry, she struggles with guilt she “could have done more.” Yet she did all she could, to bring her sister’s killer to justice — and Monday, surrounded by McPherson’s family, that truth once again shined.

Is there hope? Several people who gave testimony noted they had seen improvements in systemic responses. If so, it did not happen by chance or overnight; it happened because advocates brought truth to light.

(Listening to Sinclair speak, I was reminded of last year’s search for Christine Wood. At one point during her parents’ search, the family received a lead of murky veracity. Even still, police arrived to search the location within minutes. Those efforts couldn’t save Christine, who police now believe was killed the night she went missing. But as the tragic story of Letandre and McPherson shows, rapid interventions can save someone, even someone not yet known.)

But there was something else the inquiry heard Monday, something brighter and more lovely. Because the families spoke of light, too, and all of the things that helped carry them through — and this is something else to be learning.

Kim McPherson spoke of the grief counsellor who “saved (her) life” after her sister’s passing. She smiled as she spoke of Jennifer’s crafting and creativity; for that memory, the family offered a Christmas ornament to the inquiry.

“We have enough love and strength in our family that it hasn’t destroyed us,” McPherson said.

That is the part media sometimes misses in stories, the part that rarely shows up in a headline or in court. It is a beacon of resilience, a light of love and hope, held aloft by families who already bear the weight of the world.

Maybe, someday, we can build a society where fewer families will have to carry that burden. For now, we can honour those that light the way forward, showing us the way out of the pain of our present, and towards better days to come.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.