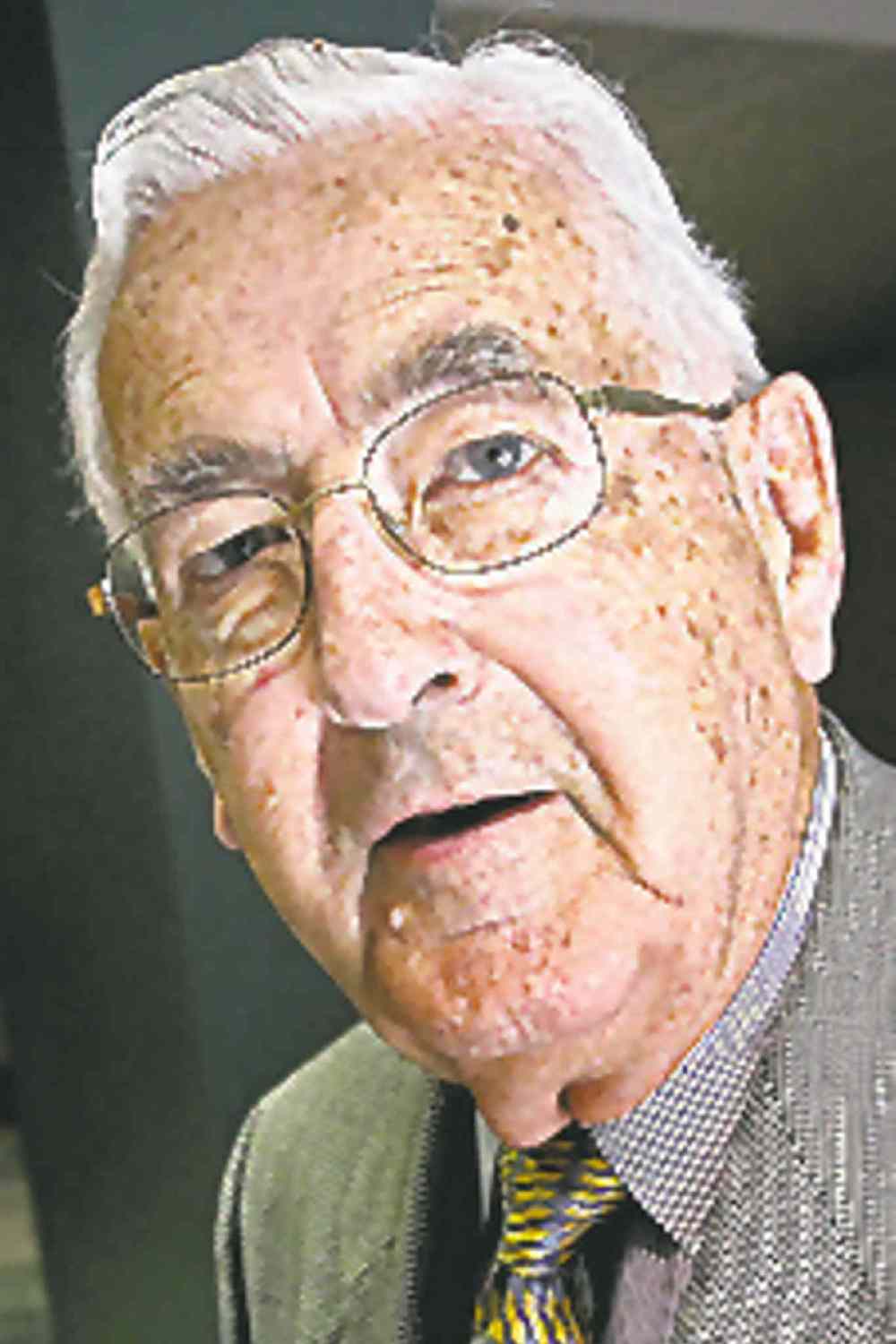

This judge doesn’t pull his punches

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/01/2014 (4332 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

IN the weeks before the worst jailhouse riot in Manitoba history, morale at Headingley Correctional Centre was lower than “a snake’s belly in a wagon rut.”

Ted Hughes, who led the 1996 inquiry into the violence that injured nearly 40 guards and inmates, called the drug search that sparked the riots “grossly irresponsible” and part of the “everyday hatred, apathy, negativism and couldn’t-care-less attitude that has taken hold at Headingley.”

Then he chided Manitoba’s justice minister for failing to keep tabs on volatile conditions among inmates and said the prison superintendent was clearly the wrong man for the job.

It wasn’t the first time Hughes, a former judge often tasked with unravelling complicated government debacles, castigated politicians and policy-makers in a vivid and frank way. He may do it again today when his report on the two-year public inquiry into the death of Phoenix Sinclair is released. If his previous work is any indication, the Saskatchewan-born Hughes will pull few punches.

“You can expect Judge Hughes to tell it like it is,” said Harvey Pollock, the Winnipeg lawyer Hughes vindicated in 1991.

Pollock represented the family of J.J. Harper, an aboriginal man the police shot, whose death led to the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry and years of acrimony and tension between police and First Nations. Shortly after the inquiry, police arrested Pollock for sexual assault, charges so specious Manitoba’s justice minister called in Hughes to launch an inquiry.

Hughes found the Pollock investigation was “unseemly” and “misguided” and the officers in charge of it irrational and emotional. He called the criminal charges “payback” for Pollock’s role in the J.J. Harper affair. His report hobbled a police department still reeling from the AJI and the sudden resignation of its police chief.

Riots, political ethics and police misconduct aside, Hughes also has considerable experience with child welfare. In 2006, after the death of an aboriginal child in care, he completed an investigation into B.C.’s child death review system and whether the province needed an independent office to advocate for children. He found a child-welfare system “buffeted by an unmanageable degree of change.”

“There has been a revolving door in senior leadership positions; emphasis in practice has shifted between child protection and family support; functions have been shifted out to the regions and then pulled back to centre; new dispute resolution processes have been introduced. And much of this has gone on against a backdrop of significant funding cuts, even though it is commonly understood that organizational change costs money,” he wrote.

The scope of the B.C. inquiry was smaller than the Phoenix Sinclair investigation, but Hughes’ practical recommendations sparked the creation of B.C.’s first independent child advocate’s office and significant improvements in the system.

maryagnes.welch@freepress.mb.ca