Politics in her blood In spite of low approval ratings for both her party and her leadership, Stefanson has no regrets as she works to build her political brand as premier

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/10/2022 (1135 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The atmosphere inside the Tundra Buggy is still buzzing 30 minutes after a polar bear sighting, and Heather Stefanson is sitting on a bench toward the back with tears welling in her eyes.

Manitoba’s first female premier is recalling the night she won a byelection to become an MLA, while the hulking buggy sways from side to side during its slow crawl along the rugged, frozen landscape in Wapusk National Park.

Amid the handshakes and hugs that evening, her late father, Julian Hugh McDonald, who unsuccessfully ran for the Progressive Conservatives in Manitoba’s 1977 election, was beaming.

The elation was tempered by a tremendous personal loss — five months before Stefanson won the Nov. 21, 2000 contest in Tuxedo, her mother, Diane McDonald, died at 64.

“It was a difficult time. My mom and I were very close, my dad and I were very close,” Stefanson, 52, said. “He was so proud. He was just really very excited when I got involved in the process, and I just remember that night when we won the byelection, the tears in his eyes.

“It wasn’t something that he was able to achieve, and here I am tearing up now, but anyway…”

She stops for a moment, laughing almost nervously, before resetting and continuing.

“He gave me advice all the way through it, and he came door-knocking with me, and it was just amazing,” she said.

Her thoughts returned to her parents when she won the Progressive Conservatives’ leadership race Oct. 30, 2021, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, defeating former Tory MP Shelly Glover by a narrow margin.

“I had lots of people who know me well come to me and say, ‘Your parents would be so proud of everything that you’ve accomplished to date,’” she said. “They’re still here sitting on my shoulder saying, ‘You go out, you get shit done…’ oh, sorry I can’t say that.”

Amid laughter, she adds: “And that’s what we’re doing, though. We’re getting shit done.”

The show of emotion — rare for any politician — comes as rain splatters against the buggy’s windows. It also comes far from the Winnipeg bubble.

The first leg of a two-day northern tour, with Deputy Premier Cliff Cullen and some of her closest aides, has brought her to the barren, sub-Arctic national park, east of Churchill in mid-October.

Diplomats from Brazil, Germany and Iceland have joined them on the tour and lunch with Frontiers North Adventures and Polar Bears International.

A Free Press reporter and photographer have tagged along on Stefanson’s first trip as premier to Manitoba’s northernmost town, where she promoted tourism, job creation and trade in the NDP-held riding.

When she sits down for an interview on the ride back to the buggy’s base, Stefanson — wearing jeans, a quarter-zip turtleneck and a Canada Goose vest — is relaxed, warm and, at times, candid.

She comes across as charming and sincere in conversations with others on the buggy ride. Her sense of humour seems to put people at ease.

It’s a contrast to what people normally see at press conferences and in the Manitoba legislature where she is far more composed and reserved. As a veteran politician in her third decade as an MLA, she tends to stick close to the script.

Her first 15 years in office were spent in opposition to the NDP. Her profile increased when the Tories won the April 2016 election, the first of two consecutive majorities under Brian Pallister.

Her time in cabinet included a seven-month stint as health minister and eight as deputy premier, but it’s only been in the last year or so Manitobans have paid full attention to her.

For many, their opinions have been shaped by her handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the decision to end public health orders and “live with” the virus, or issues such as the alarming state of the province’s health-care system.

The next election — her first as Tory leader — will be the biggest test of her political career, when it is held no later than October 2023.

It will be a referendum on the PC government’s handling of the pandemic and Stefanson’s efforts to fix problems within health care and education, fill labour gaps and tackle the rising cost of living.

Public opinion polls suggest the Tories are significantly behind the NDP, particularly in Winnipeg. Their support was already sliding when Stefanson took over from Pallister.

The biggest question is whether she can turn things around and win a third consecutive term for the PCs, or if the damage is already done.

In September, an Angus Reid survey suggested she is the least popular premier in Canada, with an approval rating of 22 per cent. Pallister’s lowest number was 32 per cent in late 2020.

If Stefanson is affected or influenced by her rating, she isn’t letting on.

“When I got into this, I knew there was going to be an uphill battle for me (and) for our party,” she said. “The thing is, we’re all focused on getting things done together. We’ve got a great team of people and we’ll keep moving in that direction.”

She turns to advice from Brian Tobin, a former Liberal MP and Newfoundland and Labrador premier.

“Set aside the noise and keep focused on what you’re trying to achieve, and, as long as you do, you can’t go wrong,” said Stefanson. “So, don’t worry about what’s going on in social media and what’s going on in the paper, the polls or all these things — just keep laser-focused on the things you can do.”

After a relatively quiet first couple of months as premier, a Jan. 12 news conference at the Manitoba Legislature provided a clear signal on how Stefanson would lead on a critical matter.

The highly contagious Omicron variant of COVID-19 was ripping through Manitoba at a faster pace than previous variants.

Hospitalizations were at a record high, putting further stress on the health-care system and staff. The virus was disrupting personal care homes and essential services.

Manitoba delayed the return to school for students following the winter break to give public health officials more time to assess the risk.

Despite calls to do more to contain the virus, Stefanson’s government resisted tightening restrictions, arguing the existing rules were already hindering businesses, mental health and childhood development.

The PCs were shifting toward what the premier would later call a “new normal,” mirroring steps taken by other provinces or countries such as the U.K. While it was highly likely everyone would be exposed to the variant, the government turned its focus to vaccinations, testing people at risk of severe outcomes, and using treatments such as antibodies and antivirals.

Stefanson conceded the public, not her government, must be responsible for limiting the spread of the novel coronavirus.

“This virus is running throughout our community and it’s up to Manitobans to look after themselves,” she told reporters at the press conference. “We must all learn to live with this virus; there must be a balance.”

Critics were quick to pounce, arguing the Tories were abandoning Manitobans. NDP Leader Wab Kinew claimed the Tories had “thrown in the towel” and given up on trying to contain COVID-19 and protect the health-care system.

Two months later, all public health orders, including face mask and proof-of-vaccination mandates, were no more.

Stefanson had already been accused of showing a lack of leadership as premier during that wave of the pandemic and as health minister under Pallister during an earlier peak in which the government faced pleas to impose tighter restrictions.

With Manitoba’s ICUs nearing a breaking point, patients were sent to hospitals out of province under her watch. One of those patients, Ebb and Flow First Nation resident Krystal Mousseau, 31, died in May 2021 following a failed attempt to airlift her from Brandon to a hospital in Ontario.

In March, the NDP pressed her during question period to call for an inquest into her death.

Stefanson stood to answer Kinew’s question, but first boasted about her son’s high school hockey team winning a provincial championship the previous night.

Two days later, after being described as callous and facing criticism on social media, she apologized.

Guiding a city, province or country through a global health crisis where lives are at stake is an unenviable task. The pandemic has shortened many political careers, with every decision scrutinized and, often, criticized.

For some leaders, questions are going to linger.

Was the government too slow to respond? Were the restrictions too lenient or too harsh? Were public health orders lifted too soon?

For her part, Stefanson is satisfied with her stewardship.

“It’s no secret that they were incredibly challenging times, not just for me but for all Manitobans and people around the world,” said Stefanson, who tested positive for COVID-19 in June. “Hindsight is 20-20, when you’re going through that and the decision-making process.

“You can only make decisions based on the best information that you have at the time. The information was changing so rapidly, as I said on an hour-by-hour, day-by-day, minute-by-minute (basis), and so I think I feel that I did the best that I could under the circumstances given the information we had at the time.

“I wasn’t alone making those decisions, we worked as a team in making those decisions.”

Politicians and public health officials faced threats as the provincial and federal handling of the pandemic caused a rift and acrimony in some corners across the country.

“There were certainly difficult situations, there’s no question,” said Stefanson. “I think it’s why we have more security right now. That’s the reality of it, and it’s a sad reality, but it is a reality.”

Stefanson has been involved in politics for most of her life thanks to her parents, who set the foundation for her eventual run for public office.

When she was seven years old, Stefanson’s father was the PC candidate for Fort Rouge in the October 1977 election. He took her canvassing while running against Liberal incumbent Lloyd Axworthy, who would go on to retain his seat. (Today, the riding is held by Opposition Leader Wab Kinew.)

“He wasn’t successful then, but I just remember that feeling of going door-to-door and being part of that democratic process,” Stefanson said of her father. “It was really inspiring to me… just how passionate my dad was about politics, but also my mom.

“It was really instilled in me at a very young age to give back to community, to get involved in your community, and politics has really been part of most of my life because of that.”

Stefanson hails from a well-to-do family and had a fortunate upbringing. Her father was president of the family business, McDonald Grain Co., before getting into real estate.

He spent more than 25 years building and developing subdivisions in the Rural Municipality of East St. Paul, according to an obituary published when he died at 80 in April 2008.

The McDonalds’ five children — Stefanson being the youngest — enjoyed motorhome trips across North America and summers at the family’s cottage on Lake of the Woods.

At home in Winnipeg, Stefanson attended top private schools — Balmoral Hall and St. John’s-Ravenscourt, graduating in 1988 — and was put on a path toward success.

After graduating from the University of Western Ontario with a political science degree, she headed to Ottawa to look for work on Parliament Hill.

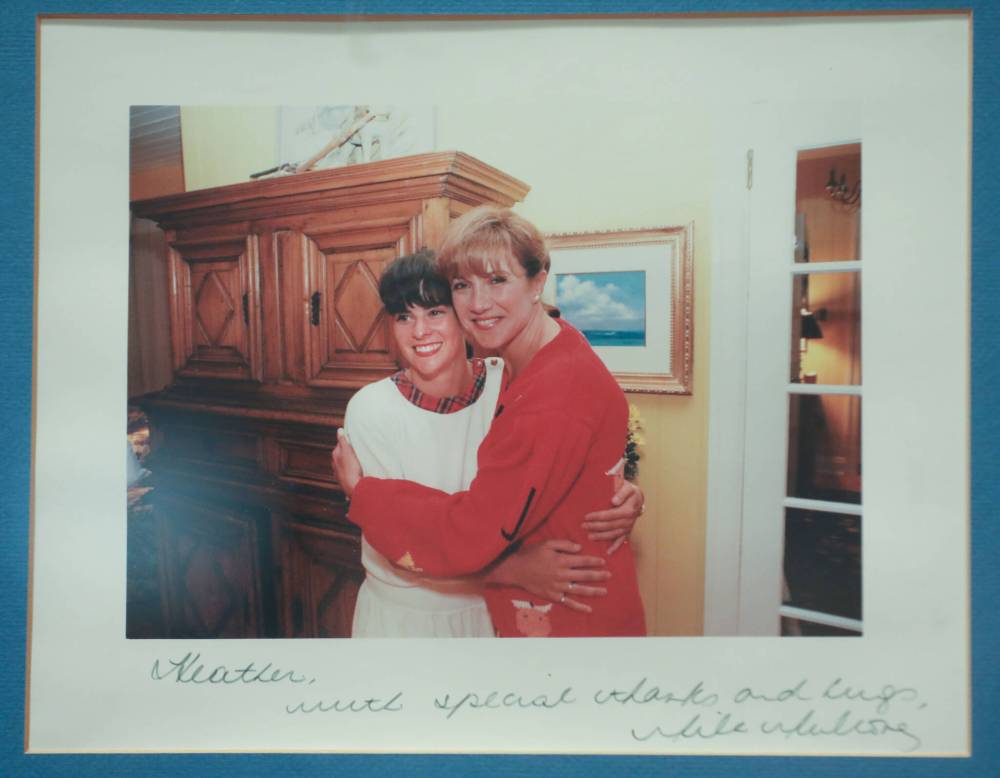

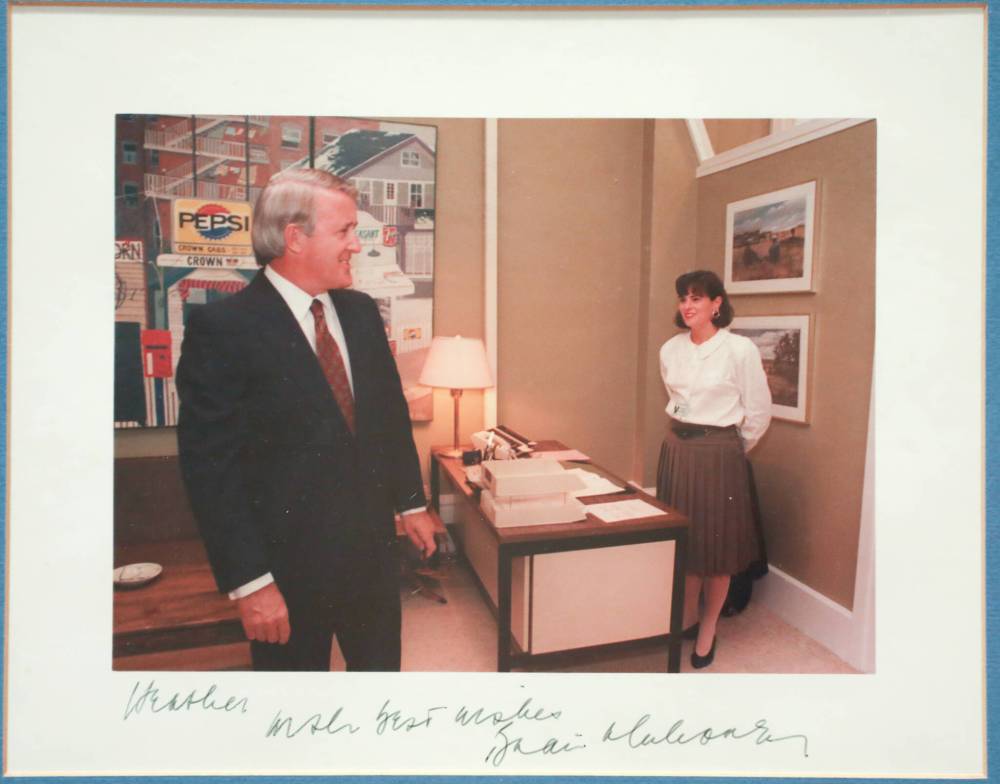

Her first gig was at a clothing store, until she landed a junior role as a special assistant to Mila Mulroney, wife of then prime minister Brian Mulroney.

“I got a lot of rejection letters. It was a tough time. It wasn’t like today where there’s a shortage of labour out there,” said Stefanson. “It was a really tough time to get a job back then, but I kept persevering.”

Glamorous and known for extravagant spending habits, Mila Mulroney was getting more correspondence at that time than her husband. She was more active than many previous prime ministers’ wives, campaigning for several children’s charities while the couple raised their four children in the public eye.

Stefanson helped sift through all the letters addressed to Mulroney, while getting a crash course on the inner workings of government.

It was a turbulent and unpopular period for the PM, whose approval rating in a Gallup survey had plummeted to 12 per cent.

In less than 18 months, Brian Mulroney would resign and the Tories — led by Kim Campbell, Canada’s first and only female prime minister — would be obliterated by Jean Chretien’s Liberals in the October 1993 federal election, winning just two seats.

Mila Mulroney remembers Stefanson coming to the office with energy. She was bright and a quick learner.

“She had a great political savvy even at the young age of 22,” Mulroney said in a phone interview from Montreal. “I didn’t have to give her much advice because she came from a political family.”

Stefanson “mapped things out” for Mulroney’s office, with the goal of synergy with the Prime Minister’s Office. There were long conversations about their objectives, how to achieve them and how long it would take.

Despite having more experience in life and in politics at the time, Mulroney believes she learned more from Stefanson than the future premier learned from her during those months in 1992.

“She’s an individual who knows what she needs to do, and she sort of directed me in that way,” said Mulroney.

Stefanson also had a deep personal connection to Mulroney’s work as national chair of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation of Canada. When Stefanson was about 12 years old, she lost a close friend and Balmoral Hall classmate who had the genetic disorder, for which there is no cure.

“She was a sweetheart,” Stefanson said. “And then she passed away, and it was really hard. I just remember being so sad, and a part of you is missing after that.

“It puts life into perspective very early on, and you start to look at things that are important and things that maybe aren’t so important.”

When Stefanson arrived in Ottawa, Bonnie Brownlee was an executive assistant to Mulroney, having been brought into the role by fellow aide Michael McSweeney, who is married to Stefanson’s sister, Heidi.

In Stefanson, Brownlee saw someone who was eager to be part of the political environment in the nation’s capital.

“Most people I worked with on the Hill, almost everyone has political ambition of some form. You could tell she definitely had an interest in being an elected official,” Brownlee said in a phone interview from Toronto.

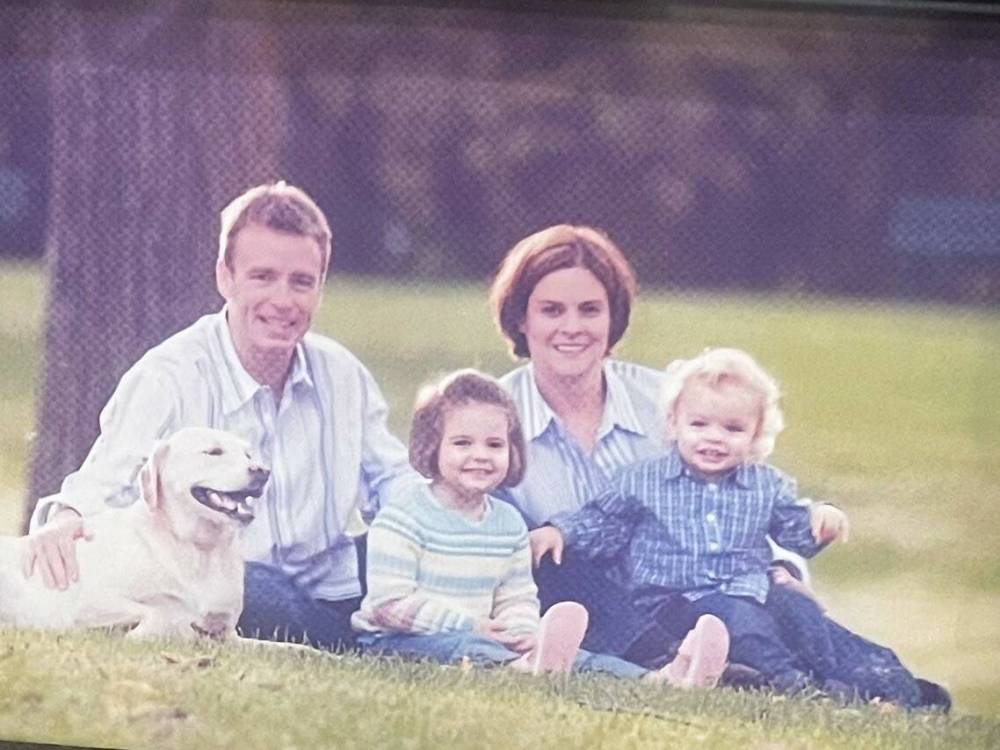

It was in Ottawa where Stefanson met her husband, Jason Stefanson, 52, a former corporate lawyer who is a Winnipeg-based vice-chairman with CIBC World Markets.

She was working for Mulroney, and he was working for Sen. Janice Johnson. Stefanson’s father played matchmaker after meeting Jason at a fundraising event in Winnipeg.

“My dad said, ‘Well I’ve got a daughter working in Ottawa,’ so he said ‘Here’s her phone number,’” she said with a laugh. “Jason called and said, ‘I talked to your dad, and your dad said I should give you a call, so I’m giving you a call.’

“I’m like, ‘Dad, seriously? What’s going on?’”

They met one day after work in 1992 in the lobby of the Langevin Block, which is home to the PMO. Next year, they will mark 25 years of marriage.

The couple’s two children — Victoria, 20, and Tommy, 18 — were born when their mother was an MLA. They’re now attending the Ivey Business School at her alma mater in London, Ont.

Stefanson laughs when she’s asked if her children have any interest in politics or could one day follow in her footsteps and pursue public office.

She suggests they’ve already seen enough from the inside.

“I don’t know about that,” she said. “They were born into this.”

While Netflix is her go-to after a hectic day at work, the premier has turned to meditation to help her relax in the morning.

“The calm before the storm hits at the office, so to speak. It’s one of those things people may not know about me, but very important, I think, to really get that in, that kind of exercising the mind,” she said.

Bonnie Mitchelson was one of three women in the PC caucus when she was elected in March 1986. The other two women — Gerrie Hammond and Charlotte Oleson — served as mentors to her while she quickly had to learn the ropes at the male-dominated legislature.

Mitchelson returned the favour after Stefanson — then an investment adviser with Wellington West Capital — won the byelection and replaced former premier Gary Filmon in Tuxedo. Filmon quit after losing the 1999 election to the Gary Doer-led NDP.

Mitchelson said she and Stefanson formed a bond at the legislature, despite being “a generation apart.”

She encouraged the rookie MLA to find her voice, while instilling lessons about policies, what the job entails, and how to balance family and career.

“I’d been involved in politics all my life, but never as an elected person, so getting to know the ropes and understanding what your (role) was really difficult at that time,” said Stefanson. “I think a lot of guys in our party, and it was a lot of guys back then, they were afraid to come to this young woman, and they were afraid to talk to me and tell me where to go and how to do things. Bonnie just took me under her wing.”

Mitchelson described Stefanson as approachable and a good listener, with a can-do attitude and a proper grasp of the issues of the day.

“I was thrilled to see a young woman step up and put her name forward back in those days,” said Mitchelson, the former River East MLA, who retired from politics in 2016. In June, she was appointed chair of the Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation board of directors by the Stefanson government. “I certainly encouraged her to express her point of view in caucus while consensus-building. She was a positive contributor to our team.”

During their time in office together — all in opposition — Mitchelson watched Stefanson develop and take on top shadow portfolios such as finance, education and health.

The future premier showed “lots of promise.”

Stefanson had been approached about running for the party’s leadership in the past, but had decided against it because her children were young. She believed the time was right when Pallister stepped down last year.

“I didn’t think Brian was going to resign, and so when that day happened it was like, ‘Wow, I guess we’ve got to get going here,’” she said. “I went back and talked to my family, and they said, ‘You know what mom? You didn’t do it before because of us, and now we’re saying to you it’s your time and we’re here to support you.’”

Having the support of much of the PC caucus convinced her to go for it. She won the leadership contest by 363 votes to become the province’s first female premier.

“We were the party that broke the glass ceiling in Manitoba,” said Mitchelson, who privately encouraged her friend to run for leader. “I was pretty proud of that, and it’s something we should all take pride in.”

Stefanson hopes to be a mentor to women like Mitchelson was to her.

After becoming Manitoba’s 24th premier, Stefanson immediately set about mending fences in Pallister’s wake, while trying to develop her own brand and distance herself from her predecessor, whose austerity measures and proposed education reform proved unpopular and whose comments suggesting colonizers didn’t mean to destroy Indigenous societies were condemned.

Stefanson isn’t the type of politician who’s going to get in your face or try to be the loudest voice in the room. There is no ego at play.

Those who know her will tell you she’s happy to sit back and listen, collaborate and let ministers run their departments.

Comparisons are inevitable, but Stefanson is the first to tell you she and Pallister don’t go about things the same way.

“Brian and I are very different people. He approached things differently,” she said. “It’s neither good nor bad, nor here nor there. It’s just the way it is. I just have a different way of doing things.”

As Mitchelson put it, Stefanson doesn’t lead in a “top-down fashion.”

“I knew from all my years working with her she would have a very different approach than Brian Pallister.”–Bonnie Mitchelson

“I knew from all my years working with her she would have a very different approach than Brian Pallister,” Mitchelson said. “The reality is, there was some team-building that needed to be done within our party. It’s not easy to turn that ship around in a short period of time.”

As a female leader, she faces questions or scrutiny a man would never receive.

“Particularly in the time that we’re in right now with social media, it can be a big challenge,” Stefanson said. “I spoke to a group of women municipal councillors out in Brandon a few months ago, and the biggest challenge that came up was just social media and having to deal with that.

“‘Oh, your hair isn’t right’ or ‘the clothes that you’re wearing are not…’ and those are the types of things I think we hear about a little bit more. Is it fair? I don’t know, but it’s just something we have to deal with. I think we deal with that a little bit more than men do.”

Mulroney considers Stefanson a role model and is proud of her accomplishments.

“She has 90 per cent of what all of us women would love to have, which is she knows exactly what she wants,” Mulroney said. “She gets up earlier than everybody, she stays up later. She manages to fill in more in her day than most everybody else.

“She thinks she’s no different than any other working woman or mother. Politics is not an easy field, but she’s very good at it.”

“She thinks she’s no different than any other working woman or mother. Politics is not an easy field, but she’s very good at it.”–Mila Mulroney

During her ascent to the premier’s office, Stefanson has been involved in controversies and made missteps, and the opposition has been quick to call her judgment into question.

She ran afoul of the former Investment Dealers Association of Canada for inappropriate trading and failure to maintain educational credentials before she was an MLA. In her leadership bid, she claimed $1,800 in expenses before the campaign had officially begun, resulting in a caution from Manitoba’s elections commissioner, who found she didn’t mean to break the rules.

And in January, Stefanson apologized for failing to disclose the sales of three properties for a combined $31 million in 2016 and 2019, as required by Manitoba’s conflict-of-interest rules.

The rental and commercial properties were owned by McDonald Grain Company, a real estate holding company that lists Stefanson as a director. The matter is currently before the Court of King’s Bench, which will decide whether a formal hearing is required.

There are few current opposition MLAs who can offer a long view of Stefanson’s career at the legislature. And fewer still who are prepared to go on the record. However, Liberal Jon Gerrard, who was elected in 1999, is one.

He said it took her some time to find her way in opposition but she was seen as a “person of promise” when she was elected in 2000.

Gerrard, obviously, is critical of her performance as a cabinet minister and premier.

“As we’ve seen, she’s had a series of missteps. The lack of preparedness has shown up time and time again.”–Jon Gerrard

He claims she wasn’t prepared and didn’t make a “sizable” impact in her roles in Pallister’s cabinet, noting she was health minister when Manitoba failed to prepare for its third COVID wave.

There was talk she would do better than Pallister when she became premier, said Gerrard, but he isn’t convinced.

“As we’ve seen, she’s had a series of missteps,” he said. “The lack of preparedness has shown up time and time again.”

The premier’s voice becomes firm while responding to a question that has likely irked her before.

She’s led a privileged life, she’s wealthy, she’s been an MLA for 22 years and she lives in an affluent part of Winnipeg.

So, is she out of touch when she talks about issues such as families who are struggling to make ends meet?

She doesn’t agree with the notion at all.

“I’ve been, from the very beginning, someone who’s out listening to Manitobans, and listening and hearing from them about the important things that need to be changed,” she said. “As long as you’re out listening to people, you’re not out of touch. You’re absolutely in touch with what people are wanting.”

As the NDP and Tories ramp up pre-election rhetoric, Kinew is already painting her as someone who is “on the side of billionaires” instead of ordinary families. Stefanson rejects that characterization.

Yet, when Stefanson announced her government’s $87 million “affordability package” in August — giving cheques to families, seniors and people on income assistance — the announcement was held in a St. Vital neighbourhood in the Riel constituency held by Families Minister Rochelle Squires.

There were many other neighbourhoods across Manitoba where those $250 cheques are needed more and where the announcement would have made more sense.

But Riel has gone back and forth between the Tories and NDP, and it will be crucial to either party’s success in the next election.

In a bid to boost her profile in recent months, Stefanson has been hopscotching across Manitoba and rolling out funding announcements or initiatives.

Affordability will be one of the key issues for voters, along with education and crime.

The crisis in health care, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic, will likely be the biggest battleground.

There are chronic staff shortages, workers are burning out, some rural and northern hospitals face ongoing disruption, and there are lengthy waits for surgical and diagnostic procedures.

Stefanson faces a tough task trying to convince voters to put their trust in the party that has overseen the slide, rather than her opponents.

As health minister, she got an up-close look at the beleaguered system when she took an unexpected leave in May 2021 for what was originally described as a “medically necessary procedure.” She later revealed it was for a hysterectomy and that she had been living in pain for more than a year.

She had the surgery at Health Sciences Centre and praised hospital staff afterward for the care she received.

“I will tell you the operation was a game changer for me,” she said at the time. “I feel absolutely fantastic now.”

On the health front today, her usual talking points include commitments to add more than 400 new nursing education seats over the next few years, to break down barriers for internationally educated nurses and, in the face of burgeoning wait times, to find ways to expand surgical and diagnostic capacity both within the provincial system, but also by sending patients out of province and to private clinics in Manitoba.

“People will say whatever they want to say, and you’ve got to put out the noise and you’ve got to be laser-focused on getting things done for Manitobans.”–Heather Stefanson

As the new chair of the Council of the Federation, a congress of Canadian premiers, she is pushing Ottawa to give provinces and territories more cash for health care.

Days before the official date of her one-year anniversary as premier, she was asked to reflect on her party’s progress under her stewardship. Stefanson said she believes her government is making some headway in tackling the health-care crisis.

“I think what Manitobans need to know is we will do what it takes to ensure they get the surgeries and diagnostics that they need when they need them, and we will not take an ideological approach that would prevent certain things like contracting out with the Maples Surgical Centre or Western (Surgery Centre), or looking at maybe outside our province right now to get those surgeries for those people waiting in pain,” she said, noting her preference is for procedures to take place in the province.

With an election on the horizon, Stefanson has zero regrets.

“I put one foot in front of the other every day. People will say whatever they want to say, and you’ve got to put out the noise and you’ve got to be laser-focused on getting things done for Manitobans, and that’s what I’ll continue to do every day,” she said. “You can never have regrets because you learn from mistakes that you make, and that carries you forward and makes you a better person.”

The interview takes place earlier this week in the second-floor premier’s office under the dome. But unlike the personal revelations in the Tundra Buggy up north, Stefanson is reserved, composed and sticking closer to the script.

chris.kitching@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @chriskitching

As a general assignment reporter, Chris covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, October 28, 2022 7:57 PM CDT: Corrects photo caption that incorrectly identified Stefanson's aunt as her mother.

Updated on Sunday, October 30, 2022 11:06 AM CDT: fixes photo caption