Alberta crisis, Winnipeg danger Staggering number of oil tanker cars rolling through city on daily basis, raising fears of Lac-Mégantic disaster in our backyard

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/01/2019 (2534 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Canada is in the midst of a politically charged debate over oil and the environment, one that will likely dominate this year’s federal election campaign.

But while the battle rages over carbon taxes and how best to send Alberta’s bottlenecked bitumen overseas, there is a de facto pipeline in the heart of the country. It operates in plain view of regulators, who do far more paper audits of safety plans than actual site inspections.

There have been no hearings into this pipeline, one that carries millions of barrels of highly flammable oil each month through the Prairies in railway tanker cars. There have been no protests about the safety concerns posed by the convoy of crude that winds its way daily through Winnipeg’s downtown, despite the explosive history lesson offered by the 2013 Lac-Mégantic disaster.

National data show Canada sent 10 million barrels of crude oil on rail cars to the U.S. in October alone. Charles Hatt, a lawyer with Ecojustice, said hardly anyone’s noticed that staggering amount.

“It’s just an aggregation of small decisions, here, there and everywhere, that amount to us now transporting” such high amounts, he said. “It’s more diffuse (than pipelines).”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s cabinet is well aware of this regulatory anomaly, with trains carrying crude every day through the riding of Jim Carr, the Manitoba minister who used to handle the energy portfolio, and is now in charge of helping sell Canada’s oil in foreign markets.

“Certainly, people have raised the issue with us,” Carr said recently. “A small number.

“I understand why, in the contemporary environment, people would — I would hope — prefer that oil is moved by pipeline, which is a safer way to move it.”

Premier Brian Pallister said he’s thankful Manitoba sits on flat terrain.

“Since Lac-Mégantic, I think everybody’s concerned about oil by rail,” he told the Free Press.

He said Alberta’s “crisis situation” justified that province’s bid to put more oil on the rails. “But it’s not, I think, perceived by most to be the best long-term solution.”

Welcome to Winnipeg, home of a unique carbon footprint in this national debate, one that is growing because the city’s history makes it the main east-west conduit for an ever-lengthening line of oil-filled train cars.

● ● ●

Black cars snake along the CN main line as it crosses over Pembina Highway from Grant Park and into Lord Roberts. Bev Pike sees trains passing through her neighbourhood every day, often with tank cars idling next to new condos.

“You can reach out and touch those trains; it’s very poorly planned,” said Pike, a co-ordinator with the South Osborne Residents Group.

Members of this community group have long opposed densification, claiming larger buildings undercut locals’ property values and access to parking spots. But recently, the uptick in heavy trains carrying oil has taken up most of the group’s attention.

“Houses are getting wrecked by extra transportation vibrations,” Pike said. “People’s doors won’t shut anymore; their foundations have big cracks.”

Pike and others suspect more oil is passing through the city. Data suggests that’s the case.

In November, the National Energy Board published data showing a staggering increase in Canada’s crude-by-rail exports, with the daily number of barrels crossing the U.S. border doubling between September 2017 and September 2018.

The amount of crude passing through the Prairies is accelerating even faster.

Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows the amount of crude oil sent from Canada to Midwest states doubled in September, compared with just a month prior.

The agency reports 849,000 barrels made that crossing in August, before jumping the next month to two million barrels, and then in October to 2,468,000 barrels — the highest month on record since the EIA started collecting this data in 2012.

!function(e,t,s,i){var n=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(i)&&(i=d+i),window[n]&&window[n].initialized)window[n].process&&window[n].process();else if(!e.getElementById(s)){var r=e.createElement(“script”);r.async=1,r.id=s,r.src=i,o.parentNode.insertBefore(r,o)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

The data includes rail lines running south from Winnipeg and tracks that run east of the city before crossing from northwest Ontario into Minnesota. It also includes one Saskatchewan line into North Dakota; industry analysts believe all three routes are being used to transport oil.

Analysts say the remaining two Ontario routes into midwestern states are far less likely used for oil; those two routes connect Windsor to Detroit and Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., with the Michigan town with the same name.

Pike’s neighbours believe they’re seeing an uptick of these oil cars, and that data suggests they’re correct. But no one will tell Winnipeggers whether that’s the case. Railway companies provide first responders with information on the materials moving through their cities, almost none of which is shared publicly.

The companies insist they prioritize safety, but she can’t take them at their word after last spring’s series of brush fires along CN’s rail lines. The company denied it was at fault; the city produced video evidence.

Meanwhile, Pike suspects the condos being built near the Fort Rouge rail yard are breaching the city’s mandated buffer zone for new builds, meant to lower the risk of rail-related catastrophes.

“What some people joke about in Lord Roberts is: ‘Well, if those things get built they will act as a buffer, between the next rail disaster and the neighbourhood, so the fireballs will hit the new condos,’” she said. “Those concerns are all top-of-mind.”

● ● ●

“Lac-Mégantic was the collateral damage of a series of political decisions,” says Bruce Campbell, a York University environment professor. “It was a question of not if, but when.”

In his new book, The Lac-Mégantic Rail Disaster: Public Betrayal, Justice Denied, Campbell examines the build-up to the explosive 2013 derailment that killed 47 people and destroyed more than 30 buildings in the Quebec town’s centre.

He said the train involved was one part of “a pipeline on wheels,” and the result of railways evading the scrutiny faced by conventional pipelines.

“What I’ve seen in my research is that the door is still open to a repeat of history,” said Campbell, the former executive director of the left-leaning Canadian Centre of Policy Alternatives.

He cites a “systematic erosion” of federal rules dating back to the late 1980s and what he deems to be regulators too heavily relying on industry to follow its rules. For him, the problem culminated in the the 2001 introduction of Safety Management System regulations, where railways form their own safety rules and Transport Canada inspects them.

Most of those inspections are done at office desks.

Documents obtained by Quebec NDP MP Robert Aubin show Transport Canada had just 25 inspectors qualified to inspect railways’ safety measures as of April 2018 out of a team of oversight personnel that numbered 141 in November 2017.

“That means the others are doing paperwork inspections, and that’s not what we need — we need people on the ground who can assess things,” Aubin said.

Transport Minister Marc Garneau insists rail safety is his No. 1 priority, and his department says it’s made Canada’s rail system safer in the five years since Lac-Mégantic.

“We will ensure the maximum safety possible for the transportation of this crude oil,” he told the Free Press. “We always focus on safety.”

In the past five years, Ottawa has forbidden companies from staffing single-person trains and phased out the tank cars that are most vulnerable to exploding. After months of debate, the government has implemented mandatory video and voice recorders that investigators can access after safety breaches.

In October, the Transportation Safety Board — an arm’s-length watchdog that probes systematic risks — removed from its watch list the transportation of flammable liquids by rail. The agency cited this progress, by both government and industry.

“We felt that they had responded the way that we asked them to back in 2016,” TSB rail specialist Faye Ackermans said. “The railways have implemented additional risk-control measures.”

Yet over the summer, the TSB warned rail workers aren’t getting sufficient training after probing a 2016 incident just north of Toronto involving a runaway train with diesel fuel and gasoline aboard, travelling at speeds of up to 48 km/h for nearly five kilometres.

Ackermans told reporters then there are “gaps between what is mandated by the regulations and what is required for some employees to do the job safely.”

The incident took place on the CN York Subdivision track, which is one of the country’s busiest lines.

“Over the last five years the number of these uncontrolled movements has been on the rise,” she warned. “Some railway employees working in key positions may lack the training or experience to safely perform their duties.”

A maxed-out rail system

Alberta Premier Rachel Notley recently announced plans to buy 7,000 rail cars, in the hopes of boosting the amount of oil being sent on trains by half. But Toronto activist Helen Vassilakos’ group Safe Rail Communities wants to make it harder to get those trains filled.

Alberta Premier Rachel Notley recently announced plans to buy 7,000 rail cars, in the hopes of boosting the amount of oil being sent on trains by half. But Toronto activist Helen Vassilakos’ group Safe Rail Communities wants to make it harder to get those trains filled.

In January 2016, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency ordered its first-ever assessment of a planned oil-by-rail terminal. Shortly after, the company scrapped its plans for the facility in Alberta’s oil sands.

The CEAA made that decision after law firm Ecojustice, arguing on behalf of Safe Rail Communities, raised a technicality. Railyard projects trigger an environmental review only when they reach a certain length or number of tracks, regardless of what commodity is being moved.

While case lawyer Charles Hatt was able to flag the project due to its size, he argues environmental reviews ought to instead focus on whether oil-by-rail terminals take measures that lower the risks for rail-side communities across Canada.

“They should also consider the spill risks on the environment and to communities, because we do know that there can be a danger here; Lac-Mégantic is the leading example,” said Hatt, who has unsuccessfully tried persuading Ottawa to use that criteria. An NDP bill tabled two years ago proposed enforcing that standard, but it got scant support.

Patrick DeRochie, a manager with Environmental Defence, argues that more oil cars will only put more pressure on a maxed-out rail system.

Coal miners, grain farmers and forestry workers have been warning that Canada doesn’t have enough rail lines and locomotives to get their commodities to market. Last fall’s bumper crop in the Prairies hit numerous snags in getting enough cars to ship grains abroad.

“Canada has a pretty antiquated rail system compared with other countries,” said DeRochie, who is skeptical of public concerns around crude being transported by rail, because oil companies have cited rail-safety risks to bolster their case for making pipelines.

“They’re actually using oil-by-rail disasters like Lac-Mégantic as a back-door argument for new pipelines. But it’s based on falsehoods,” he said. “I don’t want to minimize these concerns about rail safety that the public has, but I think they’re being manipulated, to scare people into supporting pipelines, which are just as risky.”

He believes “hysteria in the media about oil-by-rail volumes increasing” ignores the fact that rail accounts for less than seven per cent of Canada’s oil production capacity, and distracts from broader environmental questions.

But that issue hardly registers on the radar of Winnipeggers who have spent years studying the city’s rail infrastructure.

Local activist Sel Burrows led a push three years ago to have the railyard under the Arlington Street bridge relocated out of the city, primarily to remove the psychological barrier between central Winnipeg and the North End.

He said campaigners occasionally heard citizens wanting to move the risk of oil shipments out of the city, but that ranked far below concerns about class barriers and the possibilities for parks or more housing.

In any case, he’s been told that moving the yard would take at least four years, never mind the rest of the tracks located throughout Winnipeg.

“In the short term, we’re going to have quite a lot of bitumen,” Burrows said. “We’re lucky the Prairies are flat and we don’t have hills like Lac-Mégantic.”

Regardless, DeRochie believes the more that tanker cars become visible, the more that ordinary citizens in Winnipeg and elsewhere will start asking questions.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if, as we see the exports of oil by rail increase, that there will be local campaigns that will pop up to stop it.”

— Dylan Robertson

According to the TSB’s monthly statistics, there were 77 main-track train derailments between January and August 2018, up from 60 during the same months in 2017.

And 14 of those derailments involved trains moving dangerous goods, compared with five the previous year. The average number of cars involved in individual train derailments is also rising.

Part of the problem could be railways under pressure to hire staff. Last winter saw bottlenecks along rail lines that nearly repeated the disastrous 2013 harvest, which saw a lucrative bumper crop threatened by an inability to get grain moving. The railways, however, insist the need to add workers doesn’t mean they’re short-changing on safety training.

● ● ●

A handful of derailments and safety breaches within Winnipeg are probed each year by the Canadian Railway Office of Arbitration, a tribunal the railway companies formed 50 years ago.

Last spring, CP was ordered to reinstate a conductor after two breaches in the yard near the Old Exhibition Grounds in September 2016. The conductor had run a train too quickly for its emergency brakes to stop it from side-swiping another train, which derailed. In a second incident, he left another train sitting in the yard after forgetting to set its brakes.

Human error by railway employees is a key vulnerability for the sector, according to an external panel that reviewed the federal Railway Safety Act several months ago.

The panel reported to Parliament in May, and suggested more automation and data analytics could better prepare Canada for an expected uptick in rail traffic. “The current rail safety regime is not sufficient to address persistent issues and the evolving challenges and opportunities for safety in the near future,” the report reads.+

But Aubin argues the first step to improving rail safety is to make the industry more transparent.

In September, a conductor on The Pas-Churchill line died after a derailment near Thompson that sent diesel leaking into a local river.

The TSB is still investigating, but believes the incident was the result of a beaver dam that caused a washout along the Hudson Bay Railway.

The rail workers’ union claims former railway owner Omnitrax had cancelled its beaver-control program three years prior; the government has not said whether it was notified of such a change before the derailment.

Incidents like that one leave Aubin feeling companies and the federal government are eluding responsibility by limiting the information needed to property scrutinize them.

“We lack the evidence to know what state the (rail) network is in, while the minister endlessly repeats that security is the first of his priorities,” Aubin said.

● ● ●

The tankers roll through The Forks, taking a turn along the curve of Shaw Park before crossing over the Red River into St. Boniface.

Nearly every day, André Vermette spots at least one of the cars with the red hazard placard 1267 — the regulatory sign for petroleum crude oil — down the street from his home.

“I have major concerns about the amount of hazardous material that passes through,” said Vermette, who follows various municipal issues but began to focus on rail safety after the Lac-Mégantic disaster.

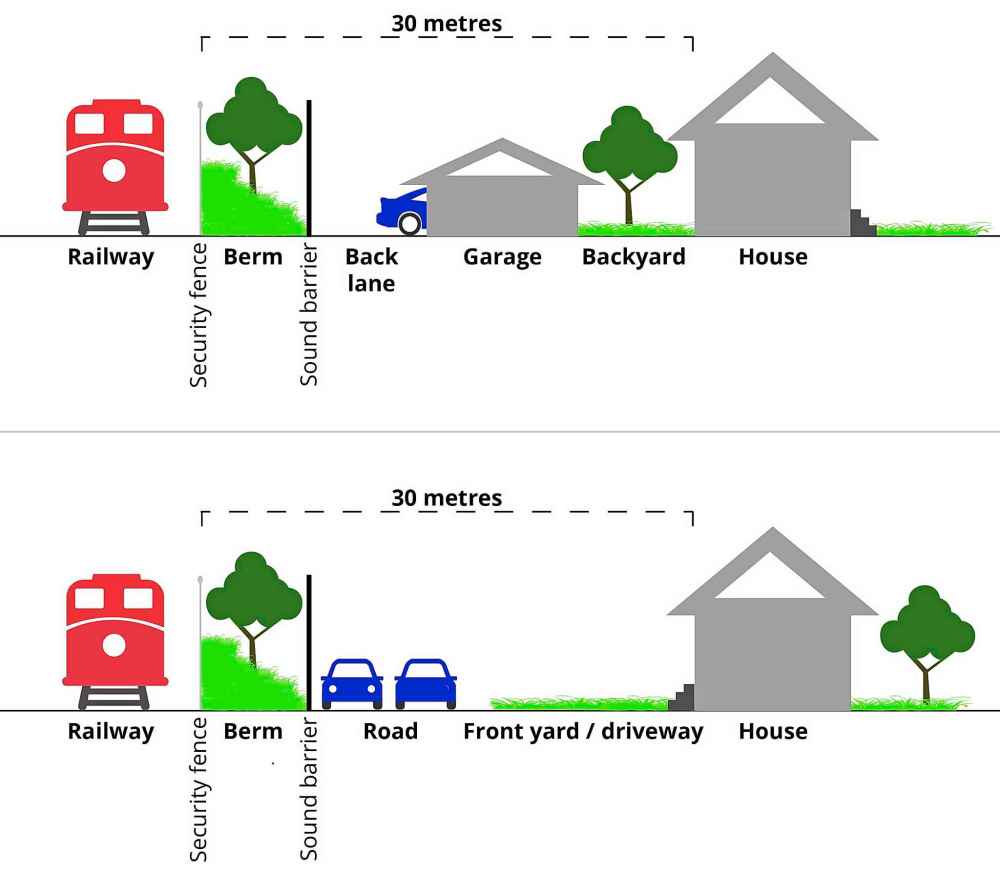

He argues the city is allowing development too close to railways, contrary to 2013 guidelines established by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, in conjunction with the Railway Association of Canada, an industry group.

The guidelines aim to mitigate safety risk, noise and vibrations by having new buildings constructed at a distance from railways with crash walls and berms for trains making turns and running on bridges.

St. Boniface city councillor Matt Allard convinced his colleagues to endorse the FCM guidelines in February 2015. The federal review last spring recommended they become law across Canada.

Those guidelines say main railway lines should have a 30-metre buffer to any new buildings, starting at the railway’s property line, and 300 metres from rail yards.

Vermette has raised issues about the condominiums proposed for 825 Taché Ave., a project that has also been tied up in a land dispute. The condo would sit 38 metres from the railway, with a planned transitway serving as a buffer.

That’s an extra eight metres of space, but the line sits on a hill; Vermette’s reading of the guidelines suggests the need for construction of a berm to catch derailing trains.

“It doesn’t take an engineer, I don’t think, to figure out that if there’s a railway on an elevated berm, there’s a greater risk to the neighbourhood,” he said. “It’s a concern for me, but I don’t really have a voice; it doesn’t seem like anybody seems to have the same concerns I do.”

Vermette raised a similar issue with Railside at The Forks. The project aims to convert 12 acres of mostly parking lots into 1,200 low-rise apartments, with street-level storefronts. Winnipeg city planners measured the setback at the railroad itself, and not the railway’s right-of-way.

The company argued there was little space left downtown to develop, and that implementing a lower speed limit was, according to their engineering assessment, “in keeping with the spirit and intent of the FCM/RAC guidelines.”

Vermette said he feels that cedes “atrocious” leeway to developers. “All this oil is passing through our city, and any derailment would be catastrophic, just as it was in Lac-Mégantic,” he said.

In January 2016, CBC published an analysis of existing Winnipeg properties that would fall short of the FCM guidelines, if they applied to more than just new builds.

The broadcaster identified nearly 15,000 parcels of land either partially or completely within the buffer zone, especially in Transcona, Fort-Rouge, River Heights, the North-End and St. Boniface.

● ● ●

In Toronto, Helen Vassilakos echoes many of Vermette’s points. She co-founded the advocacy group Safe Rail Communities in the aftermath of the Lac-Mégantic disaster.

A year earlier, her neighbours noticed “these really ominous-looking trains” passing behind their houses, something they’d never detected in the 24 years she’d lived next to a rail line.

Her group has had scant success in trying to access the risk assessments that railways submit to Ottawa, and to get Canada to follow the U.S. in strengthening its regulations. Instead, she’s received heavily redacted freedom-of-information requests and pushback from the industry.

“The issue isn’t being addressed in (any) sort of a holistic manner,” she said.

For example, her group has pushed Ottawa to have railway companies publish the types of goods they’re moving through communities, data that they hold in real time.

Instead, Garneau issued a decree in April 2016 that compels rail companies to give municipalities a breakdown of what types of hazardous good have recently been shipped through their jurisdictions.

Both of the country’s major rail companies publish the percentage of types of goods they transport through each province, but only on an annual basis. And they don’t include the size of those shipments.

In 2017, CN reported seven per cent of its Manitoba shipments involved dangerous goods, while CP reported 11 per cent of its shipments nationwide involved dangerous goods; each said a third of those shipments are crude oil.

The companies provide real-time data only to local emergency services through the Ask Rail app, which lists the contents of any rail car next to its serial number.

“It’s not made public for security reasons, which is obvious,” CN vice-president Sean Finn told Winnipeg media in July, while insisting the city is safe.

Garneau agrees with that approach:

“For security reasons, you don’t want to let the whole world know what materials you are carrying on a train; sometimes it’s company-confidential,” he said. “But also, it can have safety implications if there’s certain, dangerous materials that are being carried.

“The reality in this country is that we move a great deal by train, and some of those products are very useful products, like chlorine that we use in a number of applications, but it has to be treated as a dangerous material. And that’s why we have the safety measures.”

“Essentially the government’s tinkering with a system that needs a complete overhaul.” – Helen Vassilakos, co-founder of Safe Rail Communities

RAC spokesman Michael Gullo said railways also provide municipal emergency-planning officials with “a substantial database” of information on seasonal traffic, and the top 10 dangerous goods transported through the municipality in the last calendar year.

“Each jurisdiction’s designated emergency planning official has the discretion” to make that information public, he wrote. But the large railways restrict how much information cities can share.

Gullo also said his association runs a “safety-culture initiative” that polls railway employees on how well their company respects safety protocols, which they use to improve training.

Vassilakos said the industry could go much further.

“Essentially the government’s tinkering with a system that needs a complete overhaul,” she said, listing the numerous safety measures her group has called for.

Safe Rail Communities wants Canadian companies to follow their American counterparts in implementing automated oversight, which can halt runaway trains or slow those breaking speed limits. Such systems are already in use in municipal light-rail systems to override fatigued or confused conductors.

In the wake of the Lac-Mégantic disaster, the TSB asked railways to implement “risk-based route planning” for transporting dangerous goods, such as using alternative routes. Others have asked companies to build new railroads in rural areas. Railways responded by reducing the speed of dangerous-good shipments in urban areas.

Further, Vassilakos wants Ottawa to give financial incentives for rail companies to carry more stable forms of Alberta’s crude oil, which requires diluents to reduce its viscosity in order to be put into tank cars. She’d prefer more expensive diluent agents that reduce instead of increasing oil volatility, or mixing bitumen with a plastic-like polymer, creating pucks that can float upon water. CN recently said it plans to pilot the puck idea within three years, without any federal help.

After asking for tougher regulations and cash to support risk-mitigation measures, her group has instead secured funding from Transport Canada to publish a guide for Canadians living near railways to craft contingency plans for rail disasters. She’s thrilled by the support, but can’t help seeing it as the government conceding authority to a risky rail system.

“All we know is that we expect our government to do everything they can to make it as safe as possible — and they’re not doing it.”

● ● ●

For the former head of the Arlington rail yards, the lack of any major incident along Winnipeg’s 780 kilometres of track suggests the current system is safe.

“There’s a lot of checks and balances, in terms of everything that they do. They have electronic scanners located every (100 kilometres) along the track, which can detect any defective equipment, or anything that could potentially lead to a derailment,” said Neil Greenslade, who served as assistant superintendent with Canadian Pacific for three decades, ending in 2016.

Railways do recurring audits and constant risk assessments when they change operations or routes, Greenslade said. “I really can’t emphasize enough how much scrutiny they put on their employees, in terms of operating safely,” he said.

He said he left the industry with a feeling it was in good hands, with employees and managers held to account for mistakes. “I’ve just seen huge strides over the past 30 years in terms of safety protocols.”

If anything, Greenslade is most concerned about how easily Winnipeggers can get onto railway tracks, an issue flagged in last spring’s review of federal railway laws.

Regardless, that same review found that few Canadians trust the rail system.

“Statistics show that overall, Canada’s rail transportation system is safe. However, many Canadians remain unconvinced,” the report reads.

“Transport Canada has remained under sustained and intense scrutiny for the past several years. In this environment, the government’s assurances are often not enough to convince the public that rail transportation is safe and secure, despite a general downward trend in major rail accidents.”

The review warned public concerns around rail could match the uproar over pipelines, which has bungled major projects:

“A loss of trust can result in public opposition and ultimately limit industry operations, as has been the case in recent years on a number of resource development projects, preventing some from moving forward altogether.”

Vassilakos has helped foment some of that opposition in cities such as Winnipeg. “There are communities across Canada that are dealing with this and that are affected,” she said.

She’d like a more collaborative relationship with government and the railways. But she doesn’t imagine that will happen until people take notice of just how much oil is passing through their neighbourhoods and get vocal about it.

“It’s just shocking that a huge increase in dangerous goods was allowed to be shipped, without any risk assessments done, without any increase in safeguards put in place,” she said, sounding exasperated.

“We’re not ready for it.”

NDP documents on number of Transport Canada rail-safety inspectors

This is the first instalment in a three-part series examining safety issues along Winnipeg’s rail lines in light of a historic rise in oil being shipped by rail.

History

Updated on Saturday, January 5, 2019 10:20 PM CST: Fixes typo in pullquote.