Setting the stage

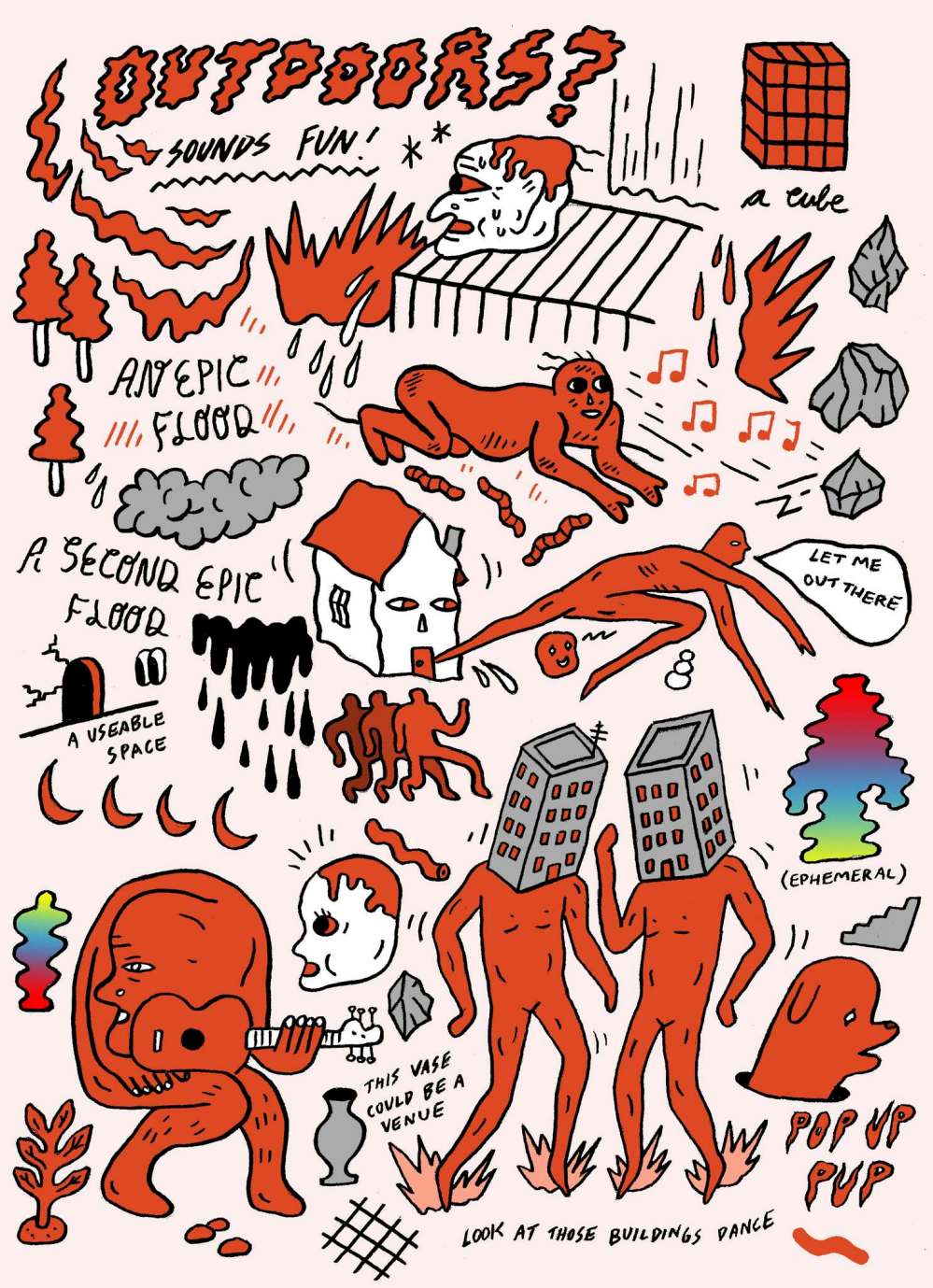

From pop-ups to iconic urban venues, outdoor places create moments for people and performers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/05/2018 (2757 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s an unseasonably warm early May afternoon and the Winnipeg Jets are only hours away from drawing thousands to the downtown core for Game 4 against the Nashville Predators when six people gather at a picnic table in Old Market Square to discuss public stages and performance spaces. Around them, food trucks set up for the lunch rush, while a group of four play Frisbee in front of the Cube, its stage lying in wait behind closed metal curtains. Sweaters are tied around waists or discarded on picnic tables as the space fills with Winnipeggers eager to soak up as much sun as they can on the first summery day of the year.

As Winnipeg’s outdoor festival season approaches, Maureen Krauss, principal with HTFC Planning & Design, opens the conversation by asking about some of their earliest outdoor performance memories.

Monica Giesbrecht, also a principal at HTFC, was born in Timisoara, Romania and has fond memories of taking in avant garde performances with her family in Piata Victoriei, a plaza outside the Romanian National Opera where her father worked. “In Europe, it’s common for many different artistic forms to be combined into one stage and the stage is often set within a large town square, very much like Old Market Square,” she explains. “On May Day everything would come outside and there’d be a festival. I was about five the first time my entire extended family went.”

Lois MacDonald, General Manager of Brandon Riverbank Inc., is currently overseeing the redevelopment of Festival Park in Brandon following two devastating floods. The park plan, which is in construction, includes a new outdoor stage and amphitheatre with seating for 3,000. She has similar memories, though in the more familiar setting of Minnedosa. “When I was a kid, it was our town centennial — a big outdoor gathering where everyone was there in a cute little park down by the rolling river; my whole family and everyone we knew in town. It was one of those really neat small town community experiences.”

As co-director of the Winkler Harvest Festival and a native of rural Manitoba, HTFC landscape designer Shannon Loewen also understands the effect of small-town get-togethers and celebrations, no matter the size or location. “Growing up on the farm, my parents never really took in a lot of festivals or events. I remember a lot of barn parties and impromptu performances from relatives,” she says.

“I’m a farm girl, too, and my family was the same. We created our own festivals!” agrees MacDonald.

That feeling of crowd-sourced ownership also applies to the inevitable rough moments at outdoor events, according to Michael Falk, artistic director of the TD Winnipeg International Jazz Festival. “I remember the Folk Fest as a kid, getting drenched and being put in a garbage bag for a poncho, probably barefoot in the mud and loving it,” he says. “There are things that, as an adult, you might find an inconvenience, but as a kid you find amazing! It’s something that, as a new dad, I try to remember. People can experience an imperfect space and it can be really positive.”

“When I was a kid, we used to go camping in the Whiteshell and at Grand Beach,” says David Pensato, executive director of the Exchange District Business Improvement Zone, “I feel like amphitheatres were more of a thing. There were usually little performances going on!”

“It’s galvanizing,” agrees Krauss, who is also a board member for the Winnipeg Folk Festival, a major gathering that sees 80,000 come through Bird’s Hill Park each year.

It becomes clear as the conversation progresses that outdoor performance space in Manitoba comes in all shapes and sizes, both specifically designed and spontaneously created. Stages function as both event venues and parks to be enjoyed throughout the year. Multifaceted as they are, these spaces raise a number of considerations for planners and designers, especially as we move toward new ways of approaching community gatherings.

Summer is here and people are flocking outside. Winnipeg is a Festival City, what do you think are some of the drivers behind our passion for outdoor festivals?

Falk: I think the weather is the first place to start.

MacDonald: Taking advantage of every moment!

Pensato: I also think our outdoor venues are, in a lot of ways, more accessible to everyone than some of our indoor spaces, which are like sealed boxes. I think it’s a little more inviting.

Loewen: I agree. I think it’s that casual atmosphere. You’re not stuck in one seat that’s been prescribed to you, you can move around and it’s not such a quiet place. You can have conversations and social interaction while you’re sitting outside that you couldn’t have in an indoor performance.

Giesbrecht: Winnipeg is a really socially cooperative city. It’s in our DNA, so we do a lot of things together. We’re not the wealthiest city, but that brings us together in different ways and I think that drives the whole festival culture. We work hard together, we play hard together. I think in the last 15 years Winnipeg has also come a long way toward an attitude of “Forget it, winter’s awesome, and we’ll have festivals in the winter, too.” So being cooped up, yes, we’re all waiting for spring, but actually I think we have a lot of fun in winter now. When I first moved here, that wasn’t true.

Krauss: Lois, is it different in rural Manitoba?

MacDonald: Rural Manitoba is driven so much by the agricultural cycle. Even bigger cities like Brandon are still connected to that. We service a region of 180,000 people whose lives are dependent on that cycle. I grew up on a farm, so a lot of times we could go to events if, for example, the cows weren’t calving. It was always a last minute thing. Brandon is still sort of a last-minute city in that way. But in outdoor venues, people have the ability to just make a decision to go. You don’t have to buy tickets and plan ahead. So I think some of the outdoor venues are more popular because they’re just more spontaneous. It helps create that energy.

Giesbrecht: You guys are pretty strategic about when you plan events, because you live that cycle.

MacDonald: We have to be. You don’t do it during spring planting, or if you’re going to do it then, do it to attract people within Brandon who are immune to that. If you’re looking for more of a regional draw, know your audience.

Krauss: Shannon, was the timing of the Harvest Festival strategic?

Loewen: It’s two weeks before the Morden Corn and Apple Festival, so we’re just ahead of their event. It’s definitely harvest time and our attendance is based directly on the weather. We always hope for rain the Thursday before the festival because if it doesn’t rain on that Thursday, the farmers will be in their fields and they won’t come out. If it rains on the Thursday, it’s wet enough that they have to take a break for the weekend and our attendance skyrockets. Even though rain on the Thursday is the worst during setup, it’s something that we hope for every year.

MacDonald: Interesting. We host Canada Day celebrations in Brandon at the Discovery Centre. The biggest one previous to last year’s 150th celebration was in 2014, when we’d had five days of epic rain. The region was basically waterlogged. All the rest of the community Canada Day festivals were cancelled because people just couldn’t do it. We were able to pull ours off and people just flocked. They were sick of trying to clean out their basements. I remember standing in the parking lot and there were just waves of people walking in. They needed a party. Weather matters, whether we like it or not.

If we were to look back from the time of the Lyric Theatre in Assiniboine Park to more recent venues such as the Cube, how have things changed?

Krauss: It seems that new venues tend to be a little more multi-functional, a little more dynamic.

Falk: I think the Lyric is still pretty active. I think what Old Market Square has become is the only public square in Winnipeg that serves that function of a central square gathering place.

Giesbrecht: The Forks is a little too far and not surrounded by dense buildings. It’s the same thing, but it’s a little too isolated to function that way. We can walk, bike or drive to The Forks for a concert…

Falk: …but it’s a destination. It’s not integrated into the natural traffic pattern, that everyday flow. In future downtown development planning, it would great to have one or two more gathering spaces like this. In Europe, they have the piazzas that really function in the community. Old Market Square has that feeling because it’s a mix of people living and working, going to school — there’s a neighbourhood that’s forming around this space. That’s the biggest change happening around here: in the last 20 to 25 years, there are a lot more people calling this place home and I think when people call it home, how they move within the community and how they live in the space changes.

Pensato: It’s been growing every five years exponentially since the ‘90s. There’s been an influx of people, activity and businesses. We have the Cube booked most of the summer. Fringe and the Jazz Festival are the big ones, but there’s something going on all the time. I know there was controversy around the new stage, maybe because it’s as much a public art piece as it is a stage, but people still come out. Festivals still run and they still draw a lot of people. It’s great for the area, it’s great for the businesses around and it’s just great for Winnipeggers.

What are the design challenges of incorporating a stage into public space?

Giesbrecht: As a designer, the biggest issue for us is designing a stage or amphitheatre or public performance venue for 3,000 people, but also making it really fun and interesting the 300 days a year when it’s not in use as a performance venue. The success of Old Market Square is that it’s a lovely park that’s comfortable and fun. You can come and have food here on an off day and you can walk through it. It’s about it being a comfortable space that you’re using in a less formal fashion when there isn’t an event on. I think that’s the big change in the last 30 years and I think older venues are taking cues. The Lyric Theatre in Assiniboine Park is screening evening movies now. It’s great!

Pensato: One of the things we’re trying to do in the Exchange District is try to expand on this a little bit. We’re planning an event in Bijou Park. It will still use the Cube as the backdrop, but the stage will face east towards Main Street, making another outdoor performance space. We’ll be screening a concert movie the first Friday of August and September. There’s a whole second venue here, when you think about it. I was involved with Alleyways Market for the last two years, so I’m always thinking about different spaces and how you can do really neat stuff in them. It’s something we’re interested in: projects to give creative people other ideas.

Thinking about the other 300 days of the year when stages aren’t programmed, do unused spaces have a detrimental effect on the greater public space?

Loewen: Absolutely. In Winkler, we have a very large area where we have a large stage. For 51 weeks of the year, it’s a big bowl, it’s empty, it’s very quiet. But I’ve also seen a bit of a change: last year we had a generous donor who built us a new backstage area. In the past we’ve brought in motor homes in order for entertainers to dress in. Now they have a backstage area with two big dressing rooms. It’s heated and cooled. It has running water, plumbing, there’s a bathroom and a big electrical sound room in the back. It’s a much more impressive space for entertainers. This year we have two or three big events that have booked the space, whether they’re using the backstage or not. Nothing’s changed for the stage and the canopy itself, but for some reason now people are starting to use and activate the space a little bit more.

Giesbrecht: There are lots of stages around Winnipeg. We forget they’re there unless they’re programmed. If they’re not, that’s OK, as long as they still feel like a nice, comfortable space.

(As Monica speaks, a tour guide leads a group of students through the square, stopping briefly by the closed Cube for pictures.)

Krauss: Lois, have you been thinking about the other days when the stage in Festival Park is not programmed?

MacDonald: We’ve thought about it lots! We talked about it a lot before we started designing the stage and we talked about how to not have a space where you have a big concrete area with one paper cup rolling through when it’s not a major event.

Krauss: It feels unloved!

MacDonald: It does! We’ve designed a space that’s beautiful and that incorporates grass and has pathways leading through it so it can be used and enjoyed. People will have picnics there. They’ll sunbathe and hang out and be in a beautiful space. The other thing that we put a lot of thought into was making it as multipurpose as possible. Not just musical performances but everything else we could think of. So I talked with lots of different festival folks about everything from our electrical outlets to where and how we were going to put clips and connections in the concrete of the stage for temporary walls.

As lead landscape architect for the new Festival Park, Giesbrecht can vouch for that.

Giesbrecht: It’s outfitted for every possibility! I think that’s the smartest thing, because you’re prepared to be as opportunistic as possible.

MacDonald: We’re trying to create a space that’s affordable for groups to come and use on a regular basis. We’ve added all the backstage space so we have a place where dancers can go and change quickly. We have as many electrical options as possible so people don’t have to bring their electricians. We can have a performance pop up on a Wednesday evening and people can show up, do their thing and it’s not going to cost them hundreds or thousands of dollars.

Giesbrecht: The City of Selkirk has recently been trying to activate their winter as much as Winnipeg. They have the festival alley initiative and because in the winter it’s much harder to have performances, they all got together and built a portable stage. They can literally haul it with a small cube van or truck and it pops up. Now, it’s so popular that all these little festivals are popping up and the stage travels to wherever somebody wants to have a little performance.

Falk: That’s great!

Pensato: Fantastic!

Krauss: The City of Winnipeg actually has a program through Parks and Open Spaces. They have a bandmobile that they rent out. You just need a way to tow it. Whenever you see a neighbourhood street festival, the bandmobile will often be there.

The phrase “pop-up” wasn’t even in our lexicon ten years ago. What are we experiencing and why are we experiencing it?

Falk: In part, we’re taking more ownership over our city and our spaces and I think the conversation in the media and amongst citizens around our civic spaces has really evolved a lot. More and more, people are thinking about our public spaces. They want our public spaces to be positive community-building places and they’re willing to put in that effort.

Giesbrecht: I think it’s the generation and the age group. There’s more time spent making things and celebrating and having fun, and it’s OK if it doesn’t last 100 years. I would say my generation missed that. I’m totally on the bandwagon now, but a younger group is really driving that.

Pensato: There’s a lot of people who don’t see that, who don’t think that way.

Giesbrecht: I agree.

Pensato: So what do you think is the trick to showing them that?

Giesbrecht: Keeping doing it, keep talking. I have the same experiences. I have friends who have chosen to live in suburbs and that’s where they prefer to get together to socialize. But for me, a big win is when you say, “You really have to come to the Jazz Fest, there’s this musician playing.” And they come downtown and say, “I haven’t been here in a decade! This is amazing!” It’s slowly bringing people along.

What else is supporting this renaissance for building community though shared experience at outdoor performances?

Falk: I think on the suburban solution front, the Jets help in that they’re bringing in people that normally don’t come downtown. A lot of people are, today, going to have a street party on Donald Street where they’ve never done that. This is the first time they’ve experienced that in an urban environment. I think while hockey isn’t always as much of a priority for some in the downtown-focused arts sector, its helping give many Winnipeggers positive urban experiences. It pushes that door open a little bit.

Loewen: Also, I think digital media is almost responsible for bringing all of those people out. Fifteen years ago they would have had this street party and it would have been posters that had to go up. You had to have this advertising budget and it was a lot more inaccessible, whereas now things like pop-ups only exist because of social media.

Pensato: I think more and more the programming has to consider the space in a way that’s going to create situations where people want to share on social media. That was one of the big successes with Alleyways Market: choosing alleyways that provide a really fantastic visual, so people were sharing that and the momentum built on itself.

So we have two ends of the spectrum: we have permanent investment and infrastructure and more of the low impact, low investment that can occur in found space. Is one better than the other?

Giesbrecht: We need both!

MacDonald: I think they go hand-in-hand. In Brandon, we’re looking at how our venue will change our community, and we believe it will, but I think once you create those kinds of events for people to go out and participate in, it really drives forward the concept of more of those pop-ups and more of that kind of activity. Then people get used to leaving their houses after seven at night and in turn it creates that willingness to be more open to the pop-up.

Giesbrecht: An interesting part is we can design any space and have these conversations, but really where we see a place come to life is in its programming. The people who program the space are the biggest contributor to the life of the space, because otherwise we’ve designed beautiful spaces nobody uses.

MacDonald: It’s always the people that make the space, really.