Flushed with excitement A Winnipeg architect's pop-up porta-potty project is a triumphant step in his decade-long human-rights campaign

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/05/2018 (2859 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s a few hours until game time — the Winnipeg Jets about to host the Nashville Predators in Game 6 of their NHL playoff series — and a crew from the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ Enviro Team is doing the dirty work most city residents won’t see. Or even know about, for that matter.

They are spraying a dumpster in a back alley just off Portage Avenue and Vaughan Street, a regular problem spot for public urination. After the spraying is finished, the crew will apply a deodorizer.

Then it’s off to the next call.

It’s a scene that plays out every day in Winnipeg’s downtown, where the Enviro Team of between eight and 16 employees usually respond to about 10 calls a day to clean up feces and urine found on storefronts or yards during summer months.

And if they didn’t?

“Well, our downtown would stink, wouldn’t it?” shrugged Dennis Rondeau, the team’s supervisor for the last eight years. “And it’s unsightly, as well.”

But also largely out of sight.

While the issue of cleaning up biohazards — blood, urine, feces, needles, vomit — is not new, the problem has reached a tipping point in major cities across Canada, Europe and the U.S.

And the answer, in a growing number of communities, involves a trip back to the future: Public toilets and washrooms.

After all, Winnipeg had several public washrooms on downtown streets, dating back to the turn of the last century. But for a myriad of reasons, they went the way of the dodo. Civic leaders are taking steps to re-introduce public facilities where they are needed most.

“As downtowns across North America and in Winnipeg started to revitalize — the more people started shopping, the more tourism, the more conventions — those needs have resurfaced over the last 10 years,” says Stefano Grande, CEO of the BIZ.

“It’s a need, whether you’re coming downtown to shop or going home after a concert or Jets game, or you’re a homeless person. It’s a need for everyone.”

But here’s the thing: The topic of human waste, and how it is dealt with, has always been an unwelcome subject. Humans, as a rule, are loath to discuss issues surrounding their own bodily functions, much less engage in a public debate on the matter.

“This whole realm is filled with taboo, something you can’t even talk about,” says Harvey Molotch, sociology professor at New York University, who is also co-editor of the book Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing.

“I think we’re deeply wired — and for very good reasons — to avoid our own shit. It is bad stuff and it will, indeed, lead to disease. So down through the ages, I think in virtually every culture, there is some acknowledgement that humans must be separated from their human waste.”

So out of sight, out of mind?

“Precisely,” Molotch replies.

This summer in Winnipeg, however, there’s an initiative designed to change that reality.

● ● ●

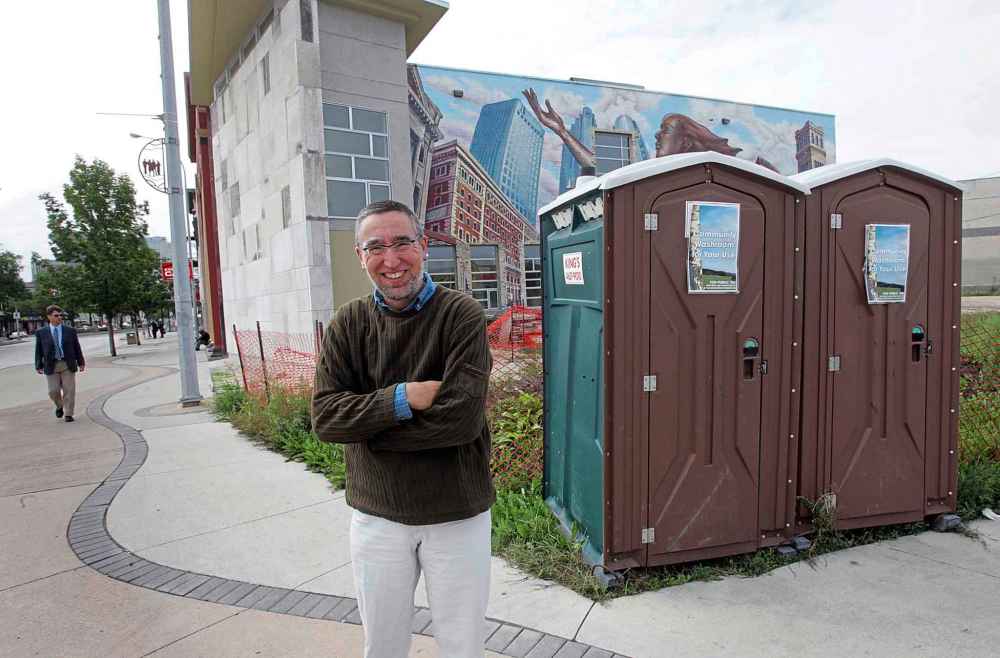

Wins Bridgman can barely contain his enthusiasm. And he’s talking about toilets.

More specifically, his mobile facility; a contraption more than a decade in the making.

“I see this and I get so excited,” the founder of BridgmanCollaborative Architecture gushes. “People are going to be surprised. We’re really dealing with a way to win over the hearts and minds of Winnipeggers.”

Bridgman is standing in a design of his own creation — a pop-up facility, still under construction, that will soon be unveiled to the general public as part of a pilot project to raise awareness of the need for public toilets in the city.

The unit, now being constructed by Keith’s Custom Sheet Metal out of a retrofitted railway shipping container — “How Winnipeg is that?” Bridgman says — contains two portable toilets, including one with wheelchair access.

Bridgman isn’t interested in designing a “conservative, quiet” washroom. His will be painted bright orange with L-shaped, five-metre-tall signage announcing, in block letters, “Pop-Up Winnipeg Public Toilet.”

“It really looks blocky,” says Bridgman, who wears an orange shirt for a photo shoot in order to be colour co-ordinated with his creation. “But it’s really going to pop-up. It’s got to be fun.”

It also has to be safe, clean and inviting, he adds.

The mobile toilet is the centrepiece of a pilot project developed in a partnership with the BIZ, Bridgman and Siloam Mission that will also include a campaign this summer to raise public awareness around the issue of public washrooms in the downtown area.

The plan is to move the facility every few weeks, beginning in June and July in front of Holy Trinity Anglican Church at Smith Street and Graham Avenue. Other proposed locations include the south side of Portage Avenue, next to Don’s Photo (July/August) and Main Street, near the WRHA building (August/September).

The entire project will cost just under $100,000, with funding coming from the BIZ, which includes design and construction of the washroom, marketing campaign and maintenance costs.

The target opening is for late May or early June. According to Grande, hours of operation with vary depending on location and needs of the area, but the general times will be between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m.

Just as important, Bridgman says, is the social enterprise component of the facility. A unique twist incorporated into the design is a kiosk that will be staffed by Siloam Mission clientele, who will be selling water and coffee, along with other yet-to-be-determined items, to passersby. All proceeds from the sales will go to the shelter.

In addition, Siloam residents will also serve as cleaning staff, and will be paid “in or around” minimum wage by the BIZ, notes the shelter’s CEO, Jim Bell.

“We’re hopeful that when people stop by to use the kiosk they will take the time, perhaps buy their coffee, buy their water and there will be a level of engagement,” Bell says.

Siloam already operates a Mission Off the Street (MOST) program, where members work with other organizations, including the BIZ, in litter cleanup and other projects.

“Now we have the opportunity to train some skills at another level so they can advance their skills and gain confidence,” Bell adds. “And as a result, you never know what might happen. The whole idea is very progressive in helping people transition in the best way they can.

“This could be the next step for many initiatives to come. We don’t see this an end, we see this as a start.”

Bridgman hopes, if the kiosk can turn a modest profit as a social endeavour, perhaps it might lead to future private/public partnerships.

“If we can get this to work where public toilets are associated with a business — hopefully, a social enterprise — that would pay for itself, it would create a model that’s unique in the world,” he reasons.

Only time will tell.

But Bridgman has already proven his penchant for patience and perseverance. After all, it was almost exactly 10 years ago when, shortly after locating his firm in a renovated bank building at the corner of Higgins Avenue and Main Street, that his interest — if not obsession — with public washrooms began.

Why? “There isn’t a day go by when I don’t see someone urinating in the corner (of his building),” he says. “There isn’t a week go by that I don’t have to clean up defecation in my yard.”

Bridgman isn’t so much upset as he is sympathetic. To him, it’s always been a social justice issue.

“Over and over again, I thought it was a case of dignity being lost,” he says, “when someone had to go to washroom (so badly) they would almost be crying and they would have to defecate in our yard. It was very sad.”

So the architect decided to take matters into his own hands, putting up his own portable toilet at the corner of Higgins and Main. But it wasn’t long before the city objected — Bridgman didn’t have a permit — and the toilet was moved off Main towards the nearby Salvation Army Booth Centre.

Eventually, after problems arose with misuse of the toilet — involving drugs, in particular — it was removed.

Not long after, Bridgman tried again, placing another public toilet behind the building. But someone set fire to it within three weeks.

Bridgman was undaunted. In fact, he became more determined to address a problem that was literally in front of his face every day.

“We needed to take a much bigger view of the issue,” he says. “This is not going to work by us doing something individually. We need to reach out to a large group of people. I was focused on my own little neighbourhood and, actually, we had a whole city of people who needed to use washrooms. It had obviously become something deeper and more important.

“In the end, washrooms aren’t about any single demographic, any single age group, any single need. It’s about — and I think it’s being discovered around the world — the revitalization of downtown. And the use of the downtown occurs with certain amenities. And one of those amenities is the washroom.

“As a white, middle-class male, you have a prerogative to believe you can go into any restaurant and you have money and you can use a washroom there. You can probably go to any public place and people will smile at you and you’ll be welcome there. There may be people who don’t feel that way. There may be places as a male that you find yourself more comfortable in terms of cleanliness than a female might be.”

That’s why, along with the pop-up pilot, Bridgman has developed an awareness campaign featuring citizens who, for various reasons, are proponents of the project. It’s called, My Winnipeg Includes Public Toilets.

Yet, when it comes to various problems facing Winnipeg’s downtown, the need for accessible public toilets is barely an afterthought for the vast majority of city residents, if they think of it at all. Maybe it’s because they have ample access to toilets. Maybe they are healthy, young and mobile. Maybe they don’t have children needing a bathroom RIGHT NOW!

“In some ways it (the dilemma) is being thought of as below the radar,” Bridgman says. “But the question is, by whom and why?”

● ● ●

So how did we get here?

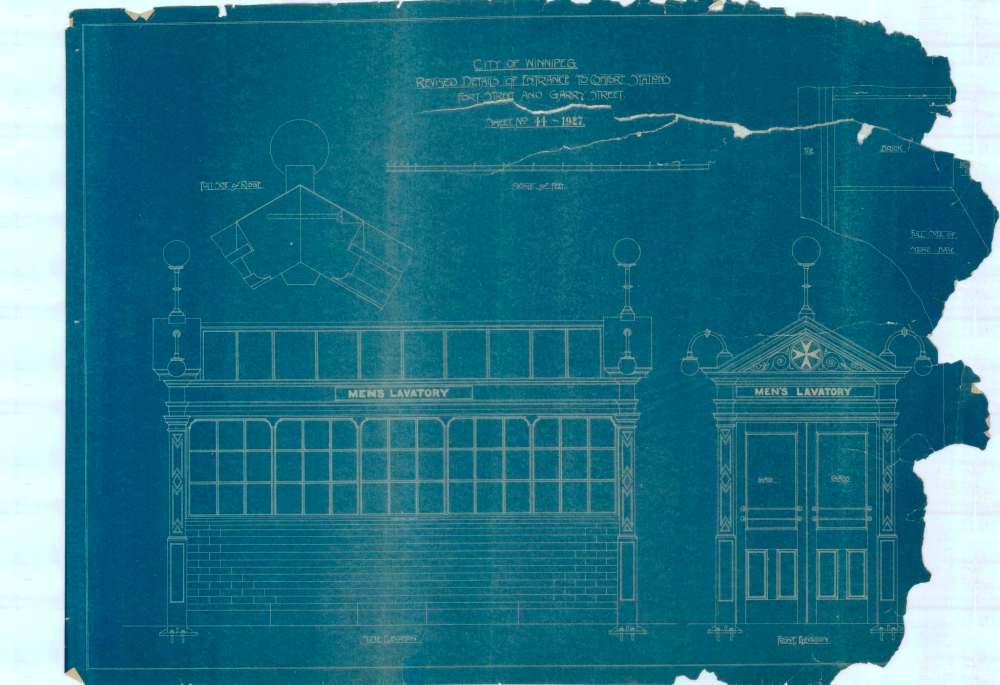

In the early 1900s, the city built five “comfort stations” — stand-alone facilities on Garry and Fort streets and Selkirk, Market and Logan avenues — for people in the core. Another was located near the old City Hall.

The underground washrooms were built of reinforced concrete, with walls of marble or white glazed marble tiles. The stairs were made of stone, with double handrails.

The price tags for these facilities ranged from $20,000 to $27,000, not a modest sum at the time.

All of the comfort stations had attendants, often war veterans, who were paid between $609.60 and $732 a year, circa 1914.

The impetus for the stations was championed largely by then-mayor Thomas Deacon who, shortly after being elected in January 1913, told the city’s board of control: “It is a scandal to Winnipeg that no public conveniences of this kind have been introduced. I’ve heard a great deal of adverse comments from visitors about our backwardness in this respect.”

Winnipeg civic historian Christian Cassidy, who has written extensively on the issue of public toilets, says women were a driving force behind establishing the comfort stations, mainly because the most accessible washrooms at the time were located in men-only saloons.

Others in the temperance movement blamed the saloons — and their amenities — for contributing to the city’s heavy alcohol consumption rate.

“They didn’t want their men to go in (to the saloon) for a pee and come out two hours later sloshed coming home,” says Cassidy, who posts historical research on his blog, West End Dumplings.

There was another major concern involved: Germs, disease and death.

Across the globe, millions were dying of cholera epidemics, with the major cause traced to fecal waste in the water supplies. This led to the Sanitation Movement of the late 1800s, in which countries, France among them, introduced the “pissoir,” or public urinal, on city streets.

Cities such as London, Paris and New York incorporated public toilets into their subway systems.

In Winnipeg, as was the case elsewhere, use of the term “comfort stations” only underlined the reluctance to call a toilet by its name. “Because the Victorians couldn’t bring themselves to talk about bodily functions,” Cassidy says.

Winnipeggers flocked to the stations in droves. A survey in 1948 showed a weekly average of 5,844 men and 1,064 women used them.

However, after the Second World War, the use of toilets operated and maintained by the city began to dwindle. The reasons varied: the presence of restrooms in more businesses and shopping centres; the physical decline and rising maintenance costs of the comfort stations; and the migration of citizens away from the downtown and into the suburbs.

“Over time, the city got out of the business of public spaces,” Cassidy says. “The cities became happy to think that a private space, even if it was used by the public, was just as good as a public space.”

Further, by the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s the comfort stations weren’t so, well… comfortable. They were often dank, unkempt and a hidden refuge for everything from drug use to illicit sex.

Instead of renovating the facilities, the city simply tore them down, often at the request of concerned local residents and business owners.

The concept of public toilets wasn’t just taboo anymore. It was toxic.

For example, Cassidy cites a 1973 case in which the province attempted to construct a washroom facility in Memorial Park near the Legislative Building. But then-mayor Stephen Juba strenuously objected to the wishes of NDP cabinet minister Russ Doern. The city refused to issue a building permit. Finally, in the heat of the debate, Juba had an outhouse delivered to the site bearing a sign declaring it to be Doern’s new office.

In the end, however, the “Broadway Biffy” was built, then later demolished in 2006.

Today, Cassidy laments that Memorial Park which, at times, draws crowds numbering in the hundreds, is without public facilities.

“It’s terrible to have a park like that — and it is a provincial park — with zero bathrooms,” he says.

September will be the 10th anniversary of Bridgman’s first ill-fated porta-potty experiment at Higgins and Main.

At the time, the city standing policy committee on downtown development unanimously passed a motion asking for a report on the matter of public toilets.

Coun. Russ Wyatt, who still represents the Transcona ward, put forward the motion while expressing a desire to bring back public facilities.

“Washroom technology has changed, and the ability to provide for that in public spaces, places is available,” he says. “It has been done in other cities, and I think there is definitely a need in certain parts of the downtown to provide that to ensure that we have a clean and attractive city.”

Says Cassidy: “You know what? That report never came back. That was 10 years ago.”

So, in many ways, history is repeating itself… a century later. The major difference, of course, is that there are plenty of toilets downtown, but almost every one is now controlled by private entities who make the rules. They decide who can and cannot use them.

Not good, says Molotch, who posits washrooms have been symbols of racism and class distinction almost since they were first introduced in America. Poor people were denied entry. So were minorities in the days of segregation.

Just last month, two black men who didn’t order anything at a Starbucks in Philadelphia were arrested for trespassing. They had asked to use the restroom. The incident sparked a firestorm of controversy surrounding race, policing and the coffee company’s policies.

“But it started with a toilet,” Molotch wrote, in an op-ed in the Washington Post.

“It could hardly be more fundamental: Going out in the city requires a way to subsist in public,” he added. “More than other needs, even food, this means having access to toilets. In lieu of plentiful and properly maintained bathrooms, Starbucks has become the public restroom of America. Along with serving up a cappuccino, its management carries the burden of toilet provision, maintenance and, controversially, deciding who gets in and by what criteria.”

Without public toilets overseen by the city, the disadvantaged and minorities are the most vulnerable, Molotch says. They are seen as the problem.

But here’s another dirty little secret: The mess of bodily fluids that BIZ crews clean up every day is not entirely produced by the homeless or indigent.

“It’s everybody,” says Steve Hughes, manager of cleanliness, maintenance and placemaking for the BIZ. “People’s perception is that it’s street clientele that are making the mess. That’s a fallacy. It’s anybody and everybody that will do it on the sidewalks and the back lanes. It’s definitely not just homeless people.”

It could be concert-goers or bar patrons. It could be someone who suffers from a medical condition, such as Crohn’s disease or colitis, who has run out of options and time.

“We know moms with kids come into our office and say, ‘Can we use your public washroom?’ We know Portage Place is overwhelmed with people who use their washrooms that aren’t even shopping,” Grande says. “There’s a need there.”

Rev. Enid Pow, who prays over the flock at Holy Trinity Anglican Church — the first location of the pop-up project — has been dealing with the cleanup of bodily fluids on the premises long enough to agree.

“I don’t know how to put this delicately, but when people have to go they have to go,” Pow says. “And if it’s behind your garbage bins, then that’s where it’s going to be.”

Pow says her father suffers from Crohn’s disease. “If he needs to go, he needs to go, like, in the next minute. So you need plenty of toilets around, otherwise people who’ve got conditions like that end up being prisoners in their own home.”

At the same time, city officials and business leaders are continuing efforts to revitalize the downtown by luring shoppers, tourists and — in recent days — tens of thousands of Jets fans to hockey-watching street parties.

Cassidy quickly points out that the Whiteout crowds are just the highly visible tip of the iceberg.

“A lot of people say they (Whiteout crowds of some 20,000-plus) are the biggest crowds in history,” he says. “Well, they’re the biggest crowds since the last Santa Claus parade. Or since the last fireworks at The Forks. We do that a number of times a year where that many people come downtown.”

The Forks, for example, attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors every year — both winter and summer. Forks CEO Paul Jordan notes all buildings at the destination site have washrooms, most of them public. There are also public washrooms at the entry of Parks Canada, on the Red River side of The Forks. Dozens of times a year, during special events, Jordan says portable bathrooms are made available, as required.

“Saying that, most people use the Market washrooms (as our cleaning bills attest),” adds Jordan in an email.

But when Cassidy goes to The Forks, he’s got his own destination spot when nature calls.

“The best public bathrooms in the downtown, though? Bar none, the (Union) train station on Main Street (adjacent to The Forks),” he says. “The best kept secret. They’re well kept. They’re beautiful, open. They smell nice. There’s security.”

Coincidentally, the architect responsible for the Union Station renovations in 2014? Wins Bridgman.

● ● ●

Winnipeg is far from alone in what could be considered a public-toilet renaissance.

San Francisco installed 25 self-cleaning toilets on their busiest streets more than 10 years ago. More than 30 public toilets — called the “Portland Loo” — have been installed in the Oregon city for a tidy sum of $90,000 each. There’s even a “Portland Loo” in Victoria, B.C. now.

A stylish, $536,000 public washroom on Edmonton’s Whyte Avenue, the heart of the city’s entertainment district, was built in 2012. And just this week, Montreal unveiled the first three self-cleaning, free-to-public toilets, with another 12 in the works at a total cost of $3 million.

There are also futuristic public toilets in Paris that automatically clean and disinfect themselves between visits. London, Tokyo and Singapore are home to networks of public washroom facilities.

But when Bridgman originally set out to design his pop-up facility, fiscal restraint was paramount.

“We’re not Paris or London or San Francisco where they have spent $500,000 for automated, self-cleaning (toilets),” he says. “We want to start small. We’re Winnipeg.”

Still, it’s clear there’s a global movement towards reintroducing, or enhancing, the access to public toilets. Why? Probably for the same reason Bridgman adopted the cause in the first place: restoring human dignity.

“Many cities have gone the way Winnipeg has (in divesting of public toilets),” Cassidy says. “And it’s just in the last few years that people have realized, ‘OK, there is an issue of dignity here.’ It shouldn’t just be shoppers at St. Vital mall who have access to a bathroom, or people in a suburban park. There are places in the city where there are zero public-accessible washrooms.

“Cities have turned their backs on them (people who need access) for so long (and) now it’s becoming something they have to deal with again after taking 40 or 50 years off of having not to worry about it too much.

“You have to give people what they need or they’re not going to come and use the amenity.”

Molotch agrees.

“I think there’s an increasing recognition that we’re all in this together,” he says. “There’s an increased emphasis in the cities… that the public sphere is to be valued in ways that it didn’t used to be. So the walking city, getting people out in public, is a way of sustaining the economy of cities, the entertainment of cities. This is all very much the current fashion.”

And don’t forget, Molotch adds, there’s the unspoken visceral human fear humans developed centuries ago.

“It’s one of the greatest humiliations,” the professor says. “I’m not a Freudian, but Freud signalled in his writings a century ago that we’re very vulnerable, all of us, to the anxiety of wetting our pants. It just goes with us and for a very good reason: our biologies are not equipped for these long times of deprivation.”

The musings of Freud aside, the goals for the pop-up toilets this summer are both practical and philosophical. Both big and small.

Grande, for example, hopes the results of the project might convince city councillors — or even private businesses — that there is a need for long-term solutions.

“It’s a real analytical approach to getting it right before spending $400,000 or $500,000 on something permanent,” he says. “But part of it is just gently creating a public conversation, where we can just sit back and engage and listen. And, hopefully, in two or three years the city will say, ‘Yeah, it’s time.’”

Even from afar, Molotch is impressed by both the social component of Winnipeg’s pilot pop-up, along with the artistic aspect of the facility. But that’s secondary, too.

“It doesn’t even matter, as far as I’m concerned, whether people use them or whether they’re feasible or whether they come out financially,” he says. “But that it becomes a topic. And anything that can make this a topic is good, right then and there.”

Bridgman, meanwhile, continues to focus on the big picture.

“I believe we live in a time in the world where we’re going through wonderful changes,” the architect says. “We’re more inclusive. The reconciliation that going on with Indigenous peoples is wonderful. The way we’re looking at gender is wonderful. The way we’re rediscovering our downtown is wonderful. These are all things that are happening in a remarkable short period of time.

“What I’m hoping for is an understanding that toilets are a part of the public fabric of our cities. And if I can contribute to making it more comfortable for everyone to be able to go downtown and enjoy being together, and having a clean, safe toilet, isn’t that magnificent?”

● ● ●

Let’s end with a delicate question for Bridgman, one of the city’s most well respected and accomplished architects.

Why toilets?

He smiles before answering.

“It’s not escaped me or my family to say things like, ‘You’re spending all this time for what? For toilets for someone to piss? Is that really a good use for your time? I thought you were an architect?’”

Yes, but… why?

Bridgman prefaces his response by saying, “I have a short answer and a long, more complicated answer.”

The short answer: “I believe more than anything else in human dignity. I believe that to be the basis of all interactions. My job as an architect is to ensure that.”

Then the long answer. You see, when Bridgman was four years old, his older brother David was paralyzed by a cancerous tumour near his spinal cord. He was eight years old and confined to a bed.

So the family designed a special chess board, made of acrylic, where David could play while lying down and looking up at the chess pieces. Wins would often lay beside him.

It was a simple, self-made device, but it allowed his brother “a huge amount of pleasure and happiness.”

David died shortly before his ninth birthday.

Now Bridgman is 62, and that memory of lying down with his brother, playing chess, has helped form the guiding principle of his life’s work.

“Reflecting over 58 years later, we have the ability to create situations for people that give joy and create a level playing field,” he explains. “What can we do to make sure that everyone has the right to participate with one another? Let’s make sure we do that, if nothing else in the world.”

So, yes, toilets.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: randyturner15

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.