Where’s the fire? Dousing flames accounts for less than 3% of calls to 911

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/12/2017 (2908 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A few summers ago, I was riding my bicycle on Wellington Crescent near the rail overpass when I hit a stone on the road and went crashing to the pavement.

For a few moments, I lay on the ground and then slowly sat up. I appeared to have suffered no broken bones, just a few nasty scrapes. Very soon, I heard a siren that heralded the arrival of a fire engine.

A passing motorist had called 911, and the firefighters were the first on the scene. Moments later, an ambulance arrived. The paramedics departed when they realized I was not seriously injured. The firefighters kindly offered to take my bicycle to their station, where I could later retrieve it. An off-duty nurse who was passing by drove me home, telling me that I was in shock. While I am grateful to those who responded, I was embarrassed by all the fuss. Why were firefighters dispatched? And then an ambulance?

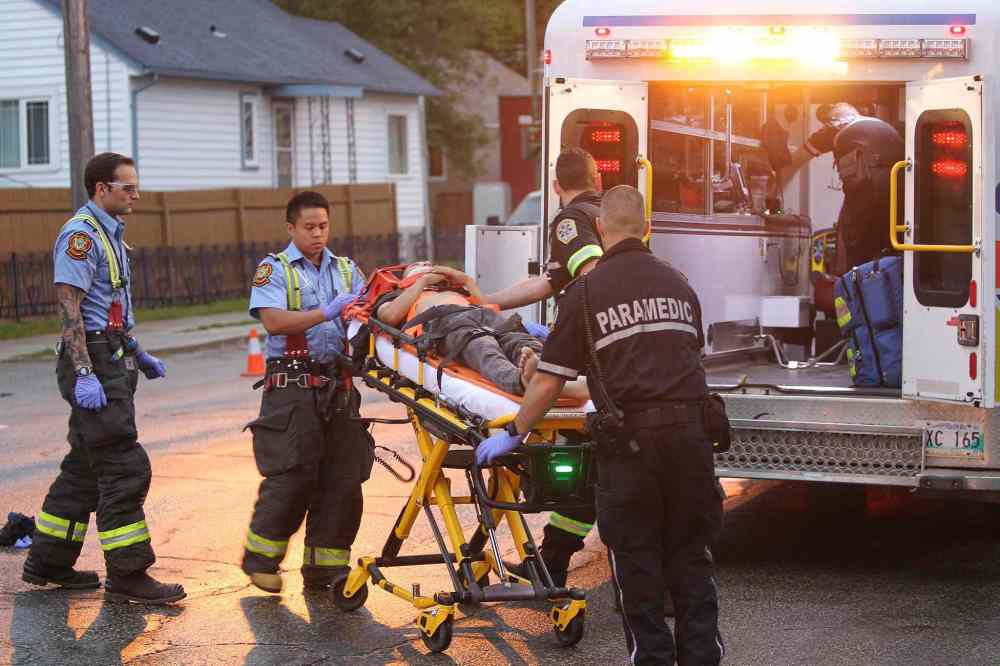

Welcome to Winnipeg’s integrated system for medical emergency response, in which firefighters — many trained as primary-care paramedics — work alongside ambulance paramedics with either primary or advanced life-support training.

The Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service has been a work in progress since the separate operations were merged in 1997.

No large city in Canada involves firefighters in emergency medical response to the extent that Winnipeg does. Only here, among big cities, do the number of professionally trained paramedics working as firefighters actually exceed those working in ambulances.

This is why it is common for a fire engine to be seen at a real — or potential — medical emergency alongside an ambulance. In fact, in Winnipeg last year, there were more than 38,000 instances in which both a fire truck and an ambulance were dispatched to a 911 call.

With more than two dozen fire stations spread evenly throughout the city, firefighters are often able to respond first to a medical emergency. But is dispatching a huge pumper truck — with four firefighters aboard, one of whom is a primary-care paramedic — to tens of thousands of calls a year the best use of scarce city dollars? Especially now that the province has frozen ambulance paramedic funding to the city at 2016 levels? And with the fire paramedic service’s overall budget reduced in the new year to $193.5 million from $199.2 million?

Winnipeg firefighters battle fewer than half the fires they did a decade ago, and the numbers continue to decline each year.

In 2007, firefighters rushed to 3,459 blazes, according to figures from the Office of the Fire Commissioner. By 2016, the number had fallen to just 1,518.

.g-artboard {

margin:0 auto;

}

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:650px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:9px;

line-height:11px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle4 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-large .g-aiPstyle5 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Fire calls, 2007-2016

Much of the drop occurred a few years ago, when the city did away with thousands of autobins and replaced them with carts. Arson fires dropped by 41 per cent in 2013.

4,000

Fire calls

2007: 3,459

Winnipeg firefighters are fighting fewer than half the fires they did a decade ago, and the numbers continue to decline each year.

2016: 1,518

500

2007

2016

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:300px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle4 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:9px;

line-height:11px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle5 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-call-trend-small .g-aiPstyle6 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Fire calls, 2007-2016

Winnipeg firefighters are fighting fewer than half the fires they did a decade ago.

4,000

2007: 3,459

Fire calls

Much of the drop occurred when the city got rid of thousands of autobins.

2016: 1,518

500

2007

2016

Source: Office of the Fire Commissioner. Note: Data varies slightly to City of Winnipeg data

Much of the drop occurred a few years ago, when the city did away with thousands of autobins — dumpster-like containers that invited arsons and illegal dumping — and replaced them with small garbage and recycling carts. Arsons dropped by 41 per cent in 2013 as the autobins were phased out, but even since then the number of fires in Winnipeg has steadily fallen. Public education and arson-prevention programs have also had a positive effect in reducing fires.

Fires currently make up less than three per cent of all incidents to which fire personnel respond. The lion’s share — about 70 per cent — are medical first-responder calls. The remainder include responses to alarms where there is no fire; gas and odour calls; miscellaneous calls and cancelled calls.

As the number of fires declines, firefighters are keeping busy attending medical-related emergencies. In 2016, they responded to more than 51,000 calls in Winnipeg, either on their own (13,063) or in tandem with ambulance paramedics (38,396). Ambulance paramedics attended another 20,414 calls on their own.

Typically, firefighter paramedics will respond on their own to motor vehicle collisions where no one is likely to be seriously hurt, or to calls to check on the well-being of an individual — for instance, a homeless person lying on the sidewalk. If a patient needs to be transported to hospital, an ambulance is called. This prevents busy ambulance paramedics from having to respond to less-serious calls.

Firefighter units provide assistance to ambulance paramedics on calls that are judged by the 911 call centre to be the most serious. Often they are the first to arrive on scene to begin administering emergency care.

.g-artboard {

margin:0 auto;

}

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:650px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-call-type-large p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-call-type-large .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-size:36px;

line-height:43px;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-call-type-large .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:11px;

line-height:13px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-call-type-large .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

#g-call-type-large .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Calls responded to by fire trucks, 2016

= 100 calls

First response

49,867

Alarms

7,742

Misc.

4,649

Includes bomb threats, explosion, recreational burning, etc

Canceled

4,272

Fire

1,496

Gas / odour

809

Rescue

180

Hazmat

56

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:300px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-call-type-small p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-call-type-small .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-size:36px;

line-height:43px;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-call-type-small .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:11px;

line-height:13px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-call-type-small .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:11px;

line-height:13px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Types of calls, 2016

First response: 49,867

= 100 calls

Alarms: 7,742

Miscellaneous: 4,649

Canceled: 4,272

Fires: 1,496

Gas / Odour: 809

Rescue: 180

Hazmat: 56

Data source: City of Winnipeg

But the heavy use of large trucks, staffed by a team of firefighters, raises questions about how efficient the system is. The fire engines are fuel guzzlers, for one thing, and are not as nimble as a smaller vehicle would be. Could the city do the job more efficiently with smaller vehicles staffed by one or two people? And with the number of fires on the decline, do we need as many fire stations and firefighters as we used to?

Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service chief John Lane argues the declining number of fires is no reason to consider reductions to the city’s firefighting complement. Winnipeg employs 862 front-line firefighters who work out of 27 fire stations. In 2012, the city had 885 firefighters but battled nearly twice as many blazes as it does now.

.g-artboard {

margin:0 auto;

}

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:650px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-station-map-large p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-station-map-large .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-large .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-large .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-large .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Fire / paramedic station with the fewest calls:

Station 27

27 Sage Creek Blvd.

36 fire calls

Station with most calls:

Station 1

65 Ellen St.

492 fire calls

Fire calls, 2016

401 – 492

301 – 400

201 – 300

101 – 200

36 -100

Fire-only station

with the fewest calls:

Station 23

880 Dalhousie Dr.

53 fire calls

Fire and paramedic

Fire only

0

5 km

2.5

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:300px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:10px;

line-height:12px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:10px;

line-height:12px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-station-map-small .g-aiPstyle4 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

1

Fire calls, 2016

2

400 – 492

301 – 400

200 – 300

Fire and paramedic

3

101 – 200

Fire only

36 -100

0

5 km

1. Station with most calls:

Station 1

65 Ellen St.

492 fire

2. Fire / paramedic station with the fewest calls:

Station 27

27 Sage Creek Blvd.

36 fire calls

3. Fire-only station with the fewest calls:

Station 23

880 Dalhousie Dr.

53 fire calls

Data source: City of Winnipeg

The staffing, equipment and infrastructure are designed to meet an international benchmark for the deployment of firefighters that dictates that there be no more than four minutes of travel time by the first crew to a fire. The NFPA 1710 standard, as it is known, was set by the U.S.-based National Fire Protection Association, a non-profit group, with input from the International Association of Fire Fighters.

NFPA 1710 "is not a binding requirement" for the WFPS, said Lane, but it’s the standard to which the WFPS adheres. (As do at least 80 per cent of the 20 largest fire departments in Canada, according to the NFPA’s Canadian rep.) Counting call processing and marshalling time, the city aims to have the first crew — four firefighters on an engine — arrive at a fire in less than 6 1/2 minutes. It seeks to have a full complement of 15 to 17 firefighters on the scene in a travel time of eight minutes or less 90 per cent of the time.

"The stations are positioned in such a way as to accomplish those response times," Lane said. "If we can’t mount an effective fire fight within eight minutes, that fire now goes beyond the room of origin."

A bit of history

Winnipeg amalgamated its fire and paramedic services — administratively — in 1997. The city attempted to reduce the number of unions representing workers in the two services but eventually gave it up after a decade of labour strife. Eventually, work-sharing agreements were agreed to that led to greater service integration. But the process evolved slowly.

Winnipeg amalgamated its fire and paramedic services — administratively — in 1997. The city attempted to reduce the number of unions representing workers in the two services but eventually gave it up after a decade of labour strife. Eventually, work-sharing agreements were agreed to that led to greater service integration. But the process evolved slowly.

By the time Dr. Rob Grierson, the WFPS medical director, arrived on scene in early 2002, integration was still in its infancy. Then-chief Wes Shoemaker, who had a background in both fire and emergency medical services, envisioned a fully integrated system similar to the ones that operate in cities such as Houston.

There, paramedics are hired and then trained as firefighters. On any given shift, depending on staffing needs, the fire paramedics will be assigned to a fire engine for calls or roam the city in ambulances, depending on where the need is greatest. Staffing changes can occur in mid-shift. If there is a greater need for ambulances, a few fire trucks can be pulled off service for a short period to accommodate that, said Grierson, who visited the Texas metropolis to view its system in action. Full integration has never occurred in Winnipeg, but it has been implemented in smaller Manitoba centres such as Brandon and Thompson.

Fifteen years ago, firefighter first responders in Winnipeg had first-aid training and their role on medical calls was simply to assist paramedics. Training eventually improved, and a “fire-medic” position was created with a training curriculum that was a pared-down version of that used by primary-care paramedics today. In 2006, provincial legislation was passed requiring that someone with the minimum training level of a primary-care paramedic be the first responder to medical calls in communities that produced 1,500 or more calls a year. Winnipeg was given a grace period to train enough firefighters to have at least one PCP on each truck.

Meanwhile, the training level of ambulance paramedics has also improved. A dozen or more years ago, there were only a few paramedics with advanced life-saving skills in the city. They tended to be employed in “chase cars” that rushed out to serious medical emergencies in support of ambulance paramedics. Now, there are more than 100 advanced-care paramedics in the field — allowing the city to staff most ambulances on any shift with at least one of these professionals.

According to a recent WFPS budget submission to city council, the average fire response time in Winnipeg last year was six minutes and 57 seconds, a bit slower than the average of 6:38 reported by 17 Canadian municipalities participating in Municipal Benchmarking Network Canada.

The fact that the number of fires is dropping has no bearing on the need for resources, in Lane’s view.

"I will say in many ways, it doesn’t matter. What matters is how quickly we can get there."

Asked whether it is financially sustainable to send big engines out on thousands of medical calls each year, Lane is adamant: "Absolutely."

He noted that the WFPS staffs three smaller vehicles — called squads — that ease some of the burden on the heavy engines in the city core. Two work out of Fire Station No. 1 on Ellen Street and one out of Fire Station 6 on Redwood Avenue. Each unit handles roughly 6,000 calls per year, making them the busiest fire vehicles on the road. Squads are staffed by a firefighter paramedic and a firefighter lieutenant.

Meanwhile, Lane insisted that the operating costs for the big engines are not as high as "those who are less in favour of our (integrated fire paramedic service) model… would purport."

Number of fire calls by station, 2012-2016

Data source: City of Winnipeg

Who are those critics of Winnipeg’s integrated model? Mainly ambulance-based paramedics and their union and professional association.

While they’re not advocating a return to separate fire and paramedic services, they are concerned about what they see as an imbalance in the level of resources provided to the two components of the WFPS.

“We work twice as hard and get paid less,” said a paramedic union source. “And when we get there, there’s a greater chance that we’re going to keep you as healthy as we can by virtue of greater medical training and greater medical competence.”

On average, Winnipeg’s ambulances (all units, including those handling inter-facility transfers) were available for calls an average of 48.86 per cent of the time in 2016, according to the city. Fire vehicles (engines, rescue, ladders and squads) were available an average of 87.41 per cent of the time.

It might come as a surprise to many that in Winnipeg, there are more professionally trained paramedics deployed on fire trucks (388) than in ambulances (296 plus 27 supervisors).

“They’re (ambulance paramedics) busy. They’re stretched thin. When they go to work, they’re at work for the day. They’re on their truck and they’re working. Whereas with fire they’ve got a lot of down time,” said Manitoba Government and General Employees Union president Michelle Gawronsky, who represents ambulance primary-care and advanced-care paramedics.

Her union has long called for an "unbiased" audit or review of the WFPS to examine the effectiveness of the service-delivery model and the resources devoted to its main components. But the MGEU said any requests for an audit or suggestions for improving the system have been met with resistance from city brass.

Several ambulance paramedics spoke to the Free Press on condition of anonymity. High ambulance utilization rates are contributing to burnout and declining morale, they said.

While ambulance paramedics say support from firefighters is needed on some calls, they question whether they need to be deployed as often as they are. Speed is absolutely critical in only a relatively small percentage of calls, they argue. But having a fire engine show up quickly with a primary-care paramedic on board allows the city to look good when comparing response times with other jurisdictions, they say.

System good for the heart

Winnipeg is one of the safest places in Canada in which to suffer a heart attack, as long as you call 911 and don’t arrange private transportation to a hospital.

Winnipeg is one of the safest places in Canada in which to suffer a heart attack, as long as you call 911 and don’t arrange private transportation to a hospital.

It’s where the city’s integrated fire-paramedic service shines, because in the case of a heart attack speed really matters.

Every primary-care paramedic in the city — including those on fire trucks — has the training and equipment to diagnose a serious heart attack in which a major artery is blocked, a condition referred to as a STEMI (ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction)

If a patient is suffering signs and symptoms of a heart attack, including chest pain or discomfort, shortness of breath and dizziness or light-headedness, a paramedic attaches a 12-lead ECG that looks at the heart from 12 different angles. The information is transmitted by the paramedic by phone via a secure data link to a physician, who will make a diagnosis.

If it is deemed to be a STEMI, staff at the Cardiac Catheterization Lab at St. Boniface Hospital immediately begin to prepare to receive the patient. Meanwhile, a physician will be on the phone to the paramedics to discuss care.

In many cases, a fire engine with a primary-care paramedic will be first on scene and will begin diagnosis, giving way to ambulance paramedics, staffed by one PCP and one advanced-care paramedic.

The advantage is that the advanced-care paramedic — who can administer life-saving drugs — is not starting from scratch when he or she arrives on scene. The PCP in the fire truck may have already applied oxygen, administered Aspirin and received information from the monitor.

The American Heart Association standard for treatment to relieve a heart artery blockage is 90 minutes. The clock starts when a paramedic arrives on scene and ends when the relatively simple hospital procedure is completed.

Now that Winnipeg has trained all its PCPs, including those on fire trucks, in the STEMI protocol, its average time citywide is 69 minutes, says Dr. Rob Grierson, medical director for the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service. The city’s treatment protocol is seen as one of the most successful in the country, and Grierson has been asked to speak about the program in other locations.

The mortality rates in Winnipeg for those who call 911 for a heart attack are dropping. Where one in 10 died in 2008, when patients were simply transported to the nearest hospital, now the mortality rate is one in 30.

"That’s all about speed," said Grierson.

His one lament is that so few people with STEMIs — 30 per cent — call 911. In 70 per cent of the cases in Winnipeg, the patient or a friend or family member arranges transportation.

"Unfortunately, taking yourself to a hospital is the worst thing you can do," he said.

Even if you take yourself to the ER at St. Boniface, the treatment time in the cath lab, just one one floor up, is 83 minutes, Grierson said. But if you called 911 from virtually any part of the city, your treatment time is 69 minutes.

"Their job is to stop that clock," said one advanced-care paramedic, referring to the fire crews.

Some ambulance paramedics contend that their colleagues on fire trucks don’t gain sufficient experience to feel comfortable performing certain procedures and are often relieved when the ambulance arrives.

"When we get there they’ve barely had time to perform an assessment or perform any interventions — if they were comfortable enough to do it — because they don’t do it enough to get comfortable and competent. And then we come in and take over," the advanced-care paramedic said.

No matter how well-intentioned primary-care paramedics on fire trucks are, he said, they can never get to be as good as they need to be; they are limited to performing duties that are required in the few minutes after arriving on scene.

"Being a paramedic," the ACP said, "is about assessing, deciding what interventions need to be performed, if any, performing them confidently and competently and then reassessing the patient based on those interventions and continuing to reassess all the way till that care is transferred to somebody else."

Dr. Rob Grierson, the WFPS’s medical director, takes issue with that analysis. He said the skill set of primary-care paramedics is relatively limited and easily maintained. And PCPs riding on fire trucks do assist ambulance paramedics in code red and amber situations, often climbing into the back of an ambulance on the way to hospital to provide an extra set of hands. Code red situations include stroke and critical trauma.

Lane said the fire paramedic service tries its best to screen calls so as not to needlessly send both an ambulance and a fire truck, "but we don’t want to miss any serious calls."

No matter the degree of urgency, a quick response is always important to patients and their loved ones, the chief added.

"If you’ve ever called for an ambulance and have been waiting for one… you will know that response time is absolutely crucial to the client. That is the lens which we look at as well, as a service provider."

In 2014, Grierson said, less than 500 of the 32,595 calls that both fire and EMS responded to failed to result in the transport of a patient to hospital.

"Sometimes it’s pretty easy to figure out (from a 911 call) that they’re really, really sick, and sometimes it’s pretty easy to figure out that they’re not that sick at all. But there’s a large portion in the middle where (someone) could be really, really sick or not sick at all," the medical director said.

"So, it’s up to us to decide how much we want to gamble with that. When we’re sending everybody (ambulance and fire), we’re sending everybody with the anticipation that we’re going to need everybody."

The paramedics union isn’t the only group that questions the emphasis the WFPS places on response time. So, too, does the Paramedics Association of Manitoba.

"Too much emphasis for far too long has been placed on response time and how important response times are. Response times are important in a small percentage of cases," said Eric Glass, PAM’s administrative director.“If you’ve ever called for an ambulance and have been waiting for one… you will know that response time is absolutely crucial to the client. That is the lens which we look at as well, as a service provider.” – Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service Chief John Lane

Glass said Winnipeg could use more ambulance-based paramedics.

"I just think far too much emphasis has been placed on how fast we get there as opposed to how good the care should be," he said.

But Grierson denies that there’s a shortage of ambulance paramedics, and Lane says the high utilization rates for ambulances are a positive thing.

"It’s what actually drives the efficiency of our model," the WFPS chief said. "We bring every resource out of them that we can. We use them heavily."

Firefighters have traditionally been among the most-trusted professionals in society — especially among city employees. Saving vulnerable people from ravaged, smoke-filled homes place firefighters high in the public’s regard.

Alex Forrest, a firefighter since 1989, a lawyer since 1996 and United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg president since 1997, knows this. But he doesn’t take anything for granted.

Forrest, who holds the rank of captain in the fire department, is a tireless promoter of the WFPS and his members. He is always accessible to the media, and his union’s advertisements promoting firefighters’ significant role as medical first responders are ubiquitous.

When the UFFW began its media blitz eight years ago, surveys showed less than five per cent of Winnipeggers knew firefighters were also paramedics.

"They wonder why a fire truck comes up when Grandma is having a heart attack," Forrest said.

In its last survey on the issue a couple of years ago, about half of city residents were aware of firefighters’ dual roles.

The union invests heavily in public relations "because when it comes right down to it, politics affects every aspect of our job — our safety or the level of (protective) clothing that we have, our workers compensation," he said.

"If we don’t educate the public about what we do for them, then maybe the politicians forget what our priorities in our city (are)… It’s a hell of a lot of work, building relationships."

Forrest has built a close relationship with Lane, the WFPS boss. Winnipeggers got a taste of how close when an arbitration case involving the paramedics’ union (Local 911 of the MGEU) revealed after-hours texts between the two men — with Forrest providing sympathy and support to the fire paramedic chief.

Forrest said because of their good reputation, firefighters are always sought by politicians for their endorsement. "It’s the firefighters’ endorsement that carries a lot of weight. We always get attacked because of our political connections. But that’s what relationships are. That’s the reason why the prime minister was able to come to our fire hall (in Osborne Village last July)."

Justin Trudeau’s visit was a coup for Forrest and his union — even though it later appeared that the mayor and the fire paramedic chief were caught unawares. It also speaks volumes about the power the UFFW wields.

College of paramedics

The union representing more than half the licensed paramedics in Winnipeg is opposed to the imminent creation of a college of paramedics.

The union representing more than half the licensed paramedics in Winnipeg is opposed to the imminent creation of a college of paramedics.

Alex Forrest, president of the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg, says the college would be “a duplication of bureaucracy.”

He said professional oversight for the city’s paramedics is already carried out by the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service’s medical director, Dr. Rob Grierson.

“At the end of the day, it really doesn’t do anything to help the front-line paramedics,” Forrest said.

Self-regulation for paramedics is one of several issues that divide firefighter and ambulance paramedics in Winnipeg.

The Paramedics Association of Manitoba, a professional lobby group, has long promoted the establishment of a college. PAM counts as its members all Winnipeg ambulance paramedics as well ambulance and firefighter paramedics in communities outside of Winnipeg. Membership is voluntary.

Of note, only a handful of the 388 city firefighter paramedics are members of PAM, the association says.

A city advanced-care paramedic, who asked for anonymity, said the powerful firefighters union is loath to support the college. “It’s about losing control of what’s going on,” he said.

The college of paramedics will act much the same as professional self-regulated colleges operated by doctors and nurses. It will license and set practice standards for paramedics, ensure they are competent, and investigate any complaints against them.

Eric Glass, PAM’s administrative director, said the college’s oversight over the profession will be “much more transparent and much more accountable to the public” than what occurs now. There will also be public representation on the organization’s governing council.

Glass rejects Forrest’s assertion that the advent of the college will lead to bureaucratic duplication. “It’s a complete transfer of bureaucracy from government to the profession that wants to act in the public interest,” he said.

After vigorously opposing the creation of a college, the firefighters union ensured in its recently negotiated collective agreement with the city that its members won’t have to be out of pocket for any registration fees charged by the new college when it’s up and running in 2019 or 2020. The UFFW secured a pledge from the city that taxpayers would cover firefighter paramedic fees. Ambulance paramedics, meanwhile, will have to pay their own fees. With an anticipated registration fee of as much as $400 annually, the city will be on the hook for an additional $150,000 per year.

Meanwhile, Grierson said he supports the creation of a college, calling it a “logical progression” in the development of the profession.

“I think it’s a logical progression and I think it’s completely necessary,” he said.

Also on the horizon, Grierson said, is the likelihood that paramedic training will transfer to universities — becoming a degree program — from the current community college model.

Maybe the prime minister’s visit escaped the city brass’s radar because every firefighter who works in a city fire station is a member of the UFFW. Not one is in management. Captains rule the fire halls. If a fire hall has more than one fire engine, that second unit is supervised by a lieutenant.

Two higher levels of supervision above the rank of captain are also union members. Platoon chiefs are the highest-ranked unionized firefighters. Under them are the four district chiefs who are stationed in each city quadrant.

Forrest, the shrewd, relentless advocate and strategist, can’t resist a dig at the paramedics’ union: "If the ambulance union representatives put 25 per cent of their effort that they do attacking us into building relationships, maybe they could get the prime minister to visit one of their units as well," he tells a reporter.

MGEU Local 911 has created a "toxic environment" in its dealings with the WFPS, Forrest said, settling their collective agreements through arbitration while the firefighters have successfully negotiated four straight contracts. The latest deal is a four-year contract that began on Christmas Day a year ago with annual increases of 1.8 per cent, two per cent, two per cent and two per cent — negotiated at a time when the Pallister government was beginning to insist that public-sector wages be frozen.

With the new contract, a basic firefighter with 10 years on the job is now earning about the same as an advanced-care paramedic with 11 years experience (the top rung of that classification) in Winnipeg.

A 10-year Winnipeg firefighter makes a base salary of $96,897 per year. A 10-year firefighter who is also a paramedic makes more — $99,666 before overtime. Meanwhile, an 11-year primary-care paramedic in an ambulance earns a base salary of $83,984, while a similarly experienced advanced-care paramedic makes $96,582.

Members of MGEU Local 911 have been without a contract with the city since February.

While the fire and paramedic unions are often at loggerheads, officials and rank-and-file staff interviewed for this story said there’s little animosity when fire units and ambulance paramedics are working together on the ground.

"We get along with front-line ambulance (personnel). Our guys and women work very well with front-line ambulance. We’re part of a team," said Forrest. "I’ve never heard of one issue of patient care on the street (as a result of any bickering)."

An advanced-care paramedic agreed that the two groups work well together, adding they don’t have a choice.

"There’s a patient that needs help and that has to be No. 1," he said. "That is what we’re trained to do."

In some cases, the relationship is quite close between the two groups, he said. "I had 10 guys in my wedding party and everyone of them was a firefighter… I have good friends who are paramedics getting married to good friends who are firefighters."

Ambulance paramedics say city brass is often defensive when they suggest system improvements. They’ve proposed making advanced-care paramedics available in a sedan or SUV to attend critical calls in place of large fire vehicles.“If we don’t educate the public about what we do for them, then maybe the politicians forget what our priorities in our city (are)… It’s a hell of a lot of work, building relationships.” – Alex Forrest, president of United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg

They’ve also suggested stationing more paramedics in the community to work with frequent 911 callers to cut down on ambulance calls and transports to hospital. Some within the WFPS administration are supporting the idea, but when the province froze grants to the paramedic service, this was one of the first areas Lane suggested might fall by the wayside.

Sometimes accused of wanting to split the fire and paramedic services apart, the ambulance paramedics the Free Press spoke with say they’re looking for system improvements — not a complete overhaul. One said the answer is more complex than simply putting more ambulances on the street.

"One of the reasons why nobody wants to talk about this in any serious detail is it gets complicated, it gets messy, it gets confusing," said the advanced-care paramedic. "You have 15 minutes with a city councillor to talk about it and they just glaze over because it’s not a 15-minute issue."

.g-artboard {

margin:0 auto;

}

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:650px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-funding-large p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle4 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-large .g-aiPstyle5 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Fire and paramedic operating budget adjusted for inflation, 2002-2018

This year was the first the department saw a decrease in recent years.

$200 M

2018: $193.5 M

2002: $119.5 M

$100 M

2002

2018

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

width:300px;

}

.g-aiAbs{

position:absolute;

}

.g-aiImg{

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-fire-funding-small p{

font-family:nyt-franklin,arial,helvetica,sans-serif;

font-size:13px;

line-height:18px;

margin:0;

}

#g-fire-funding-small .g-aiPstyle0 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:center;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-small .g-aiPstyle1 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:9px;

line-height:11px;

font-weight:300;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-small .g-aiPstyle2 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

text-align:right;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-small .g-aiPstyle3 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:12px;

line-height:14px;

font-weight:700;

color:#000000;

}

#g-fire-funding-small .g-aiPstyle4 {

font-family:Open Sans,sans-serif;

font-size:9px;

line-height:11px;

font-weight:300;

color:#000000;

}

.g-aiPtransformed p { white-space: nowrap; }

Fire and paramedic operating budget

$200 M

2018: $193.5 M

2002: $119.5 M

$100 M

2002

2018

If an engine is out on a medical call, what happens if a fire breaks out near its station? Only two of the city’s 27 fire halls have more than one engine. A unit out on a medical call puts them out of position to fight a fire.

In Wichita, Kan., a city just over half the size of Winnipeg, the lack of availability of fire crews due — at least in part — to the frequency of response to non-fire calls has become an issue.

Misty Bruckner, director of the Public Policy and Management Center at Wichita State University, has studied the management of fire resources in her community and, to a lesser extent, across the U.S. (In Wichita, the city operates the fire department, while ambulance service is the responsibility of the local county.)

In Wichita, as in Winnipeg, medical calls are making up an increasing percentage of a firefighter’s work. Many are non-emergency calls, she noted.

Bruckner found that in 2014, 15 per cent of calls to the fire department in Wichita’s city core were responded to first by firefighters from outside the area, because the closer units were out on other calls.

"They were having to pull engines or other trucks from other areas, which impacts response time and can lead to loss of life or loss of property," she said.

No comparable study has been done in Winnipeg, although the city is compiling figures as part of a "standards of coverage study" that should be completed early in the new year, city spokeswoman Michelle Finley said.

"The WFPS does not consider delays to fire response, due to firefighter-paramedics responding to medical calls, to be an issue for the department," she said in an email. "The WFPS’s response times to both fire and medical emergencies have been some of the best in the country for a number of years."

Finding the right balance in the deployment of fire and paramedic resources is a North America-wide issue, and there are no easy answers, Bruckner said in an interview.

"When you need that fire truck, it’s a resource that you have to have," she said.

There’s little research being done in the area, so Bruckner fields media calls from far and wide on the evolving role of fire departments. In many communities, questioning the size of investment in fire suppression is off limits.

"Firefighters and fire departments are ridiculously popular among the public. This is part of the conversation, right? And they are great people who do great things in our community… So how do you respect that and support that… and still have the conversation about… how you best use those resources?"

Functions of PCPs and ACPs

There are four paramedic categories set out by the Paramedic Association of Canada. They include emergency medical responder (EMR), primary-care paramedic (PCP), advanced-care paramedic (ACP) and critical-care paramedic (CCP).

There are four paramedic categories set out by the Paramedic Association of Canada. They include emergency medical responder (EMR), primary-care paramedic (PCP), advanced-care paramedic (ACP) and critical-care paramedic (CCP).

In Winnipeg, there is at least one primary-care paramedic (PCP) serving on each four-person fire engine crew. Ambulances are staffed by PCPs and ACPs.

Primary-care paramedics offer a basic life support level of care. They can perform all the tasks of an EMR (basic airway management, oxygen therapy, automated defibrillation, CPR, spinal immobilization, vital sign evaluation) plus:

• Intermediate airway management, including BIAD (blind insertion airway devices)

• 4-lead electrocardiogram monitoring and interpretation

• 12 lead electrocardiogram placement

• Peripheral intravenous cannulation

• Intravenous infusions of fluids

• Pain control with nitrous oxide

• Administer bronchodilators to patients experiencing respiratory emergencies

• Administer ASA (Aspirin) and nitroglycerine to patients experiencing chest pain

• Administer D50W (Dextrose) intravenously and Glucagon via intramuscular injection to patients experiencing diabetic emergencies

• Administer epinephrine via intramuscular injection to patients in anaphylaxis

• Administer naloxone in case of opiate overdose

Advanced-care paramedics provide advanced life support. They have all the skills of a PCP plus (among other things):

• Advanced airway management, including endotracheal intubation, nasotracheal intubation and emergency surgical airway

• Advanced suctioning techniques, such as deep tracheal suctioning and deep chest suctioning.

• Use of positive pressure breathing adjuncts, such as Constant Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

• Advanced resuscitation techniques, such as cardiac defibrillation, cardioversion (chemical and mechanical) and pacing

• Cardiac pacing

• Administration of more than 40 medications via topical, oral, sublingual, rectal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, endotracheal, nebulized, umbilical, intralingual and intradermal routes

• Needle thoracentesis (decompression)

• Perform arterial cannulation and retrieve arterial blood samples

• Urinary catheterization

Source: Alberta Paramedic Association website

Bruckner said there are probably "quiet debates happening" in some quarters about the appropriateness of current fire-response standards. Improved fire codes and greater use of sprinkler systems in buildings could potentially lessen the need for such strict response standards as NFPA 1710, she said. But these conversations are "very difficult" for government leaders to have, she added.

Phil Keisling, director of the Center for Public Service at Portland State University, said there is "very little good systematic thinking" on how best to optimize fire services.

"This is a just-in-case system. And it’s one of the few places in local government spending where this just-in-case notion has stuck around for so long," he said. "Would you be able to give up half-a-minute of theoretical response time in a fire to put that money into ambulances that might save dozens of lives because (a) you might get there quicker and (b) you might get there quicker with a higher level of trained people?

"Don’t think that the only standard in this world is how quickly you need to respond to a fire. That’s what I would argue as a former elected official (he was a state legislator in Oregon)."

There are two City of Winnipeg-commissioned reports on the horizon that are expected to have a bearing on the future deployment of fire and paramedic resources.

One is the Fire Underwriters Survey, commissioned three years ago and still not released. The report will assess the status of the city’s firefighting capability and recommend improvements, including new equipment and fire stations.

The last FUS report in Winnipeg was completed nearly three decades ago. It is used to set insurance premiums for property owners. In the last survey, the city received a score of 2. The potential grades are 1 through 10, with 1 being the best score.

The second anticipated report is the aforementioned "standards of coverage study" being carried out by American-based Emergency Services Consulting International. The company is assessing fire risk and medical calls in the city.

It is expected to examine resources and staffing in various parts of the city, point out areas that are under-serviced and even recommend the long-term repositioning of fire and paramedic stations. The city says this type of study has never been done in Winnipeg before. No release date has been given for the report.

Also hanging over the WFPS is the threat by city politicians to turn over ambulance service to the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority — and by extension the province — in a dispute over funding. Ambulance service, by law, is a health authority responsibility. The health authority contracts out the service to the city, but it has announced it is holding grants to 2016 levels.

The UFFW’s Forrest said he hopes the funding issue is resolved. He claimed that a transfer of ambulance services to the WRHA "could be devastating" for front-line ambulance staff due to potential changes in working conditions and assignments.

Firefighter numbers would be unaffected by the change due to the need to adhere to response-time standards, he said. In fact, the role of fire paramedics could be enhanced if the WFPS were to give up its ambulance contract, Forrest suggested. Many could be trained to provide advanced life support "at a very minimal cost for the province," he said.

An official with the MGEU, which represents ambulance paramedics, said while the union has no control over the city’s decision, it will fight to ensure that the paramedics and emergency medical services dispatchers it represents do not suffer as a result and that patient care and professional paramedic practices are maintained.

"It’s important that we raise the standards for patient care for all Manitobans, not lower them to achieve a cuts-driven agenda," he said.

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, December 26, 2017 8:13 AM CST: Typo fixed.