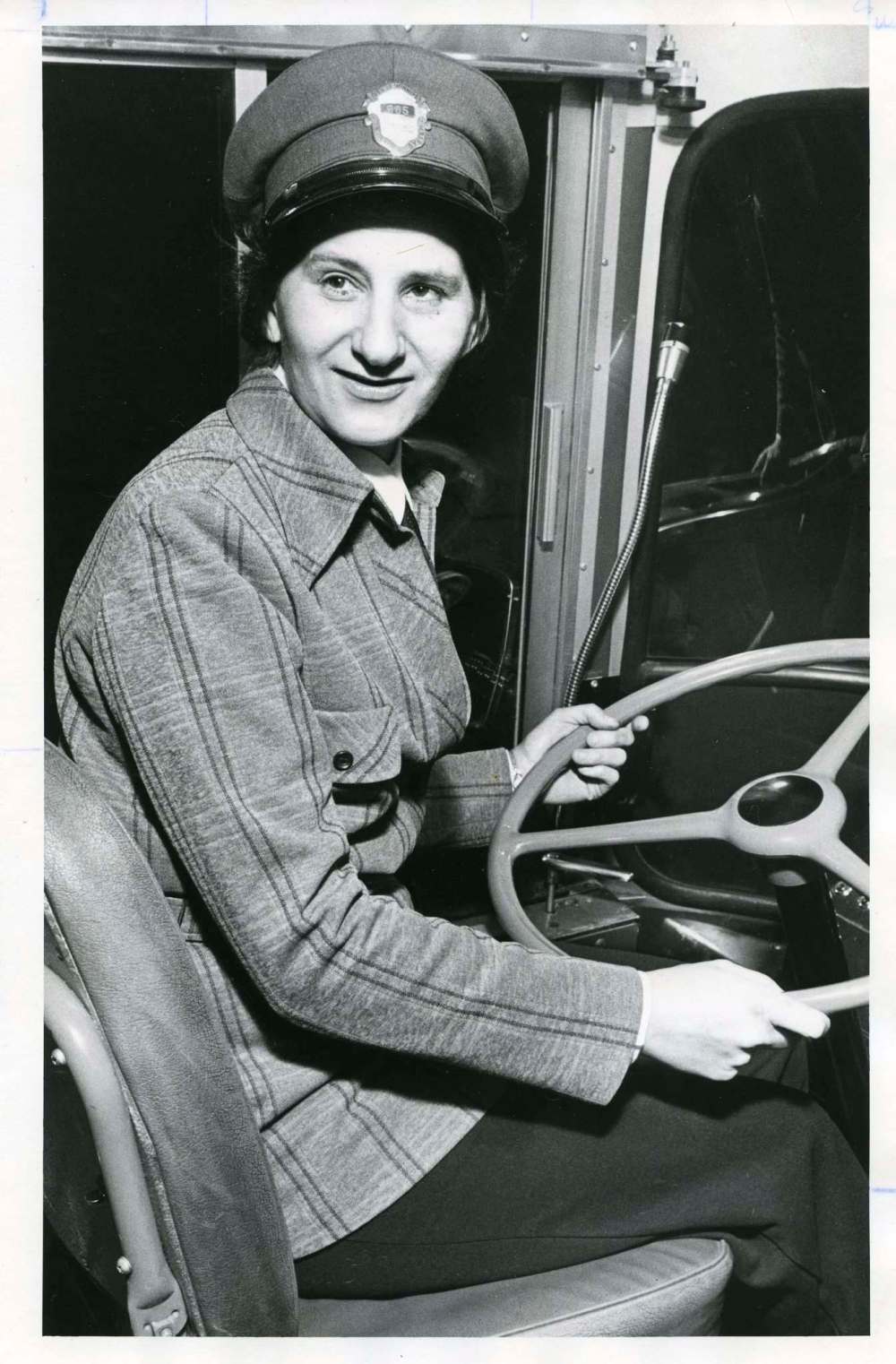

The woman behind the wheel

Mary Staub broke new ground in 1975 as Winnipeg's first female bus operator

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/11/2017 (2940 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On the afternoon of Jan. 2, 1975, Winnipeg Transit bus number 647 rolled out of the North Main Street garage to begin service on the Main — Corydon route. It was a scene that had played out thousands of times before, but what made this trip front-page news was Mary Staub, Winnipeg Transit’s first female bus operator, was heading out on her debut run.

Staub, who was in her early forties at the time, already had a lifetime of hard work behind her.

Born during the Depression in East Kildonan, Staub was raised on a farm 25 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg. She returned to the city to attend United College and received her teaching certificate in 1949.

Staub chose to teach at a school in the primarily Aboriginal community of Barrows, Man., about one hour north of Swan River. That is where she married Fred Staub and they returned to Winnipeg to raise their family.

Staub then spent a decade as a housing manager for Manitoba Housing working in the newly-built, housing developments of Lord Selkirk Park and Gilbert Park. In 1970, she left to take a job at the administrative office of Red River College.

By 1974, Staub was separated from her husband and raising five children ranging in age from 12 to 20. On top of her college job, she also worked at a bar to help make ends meet.

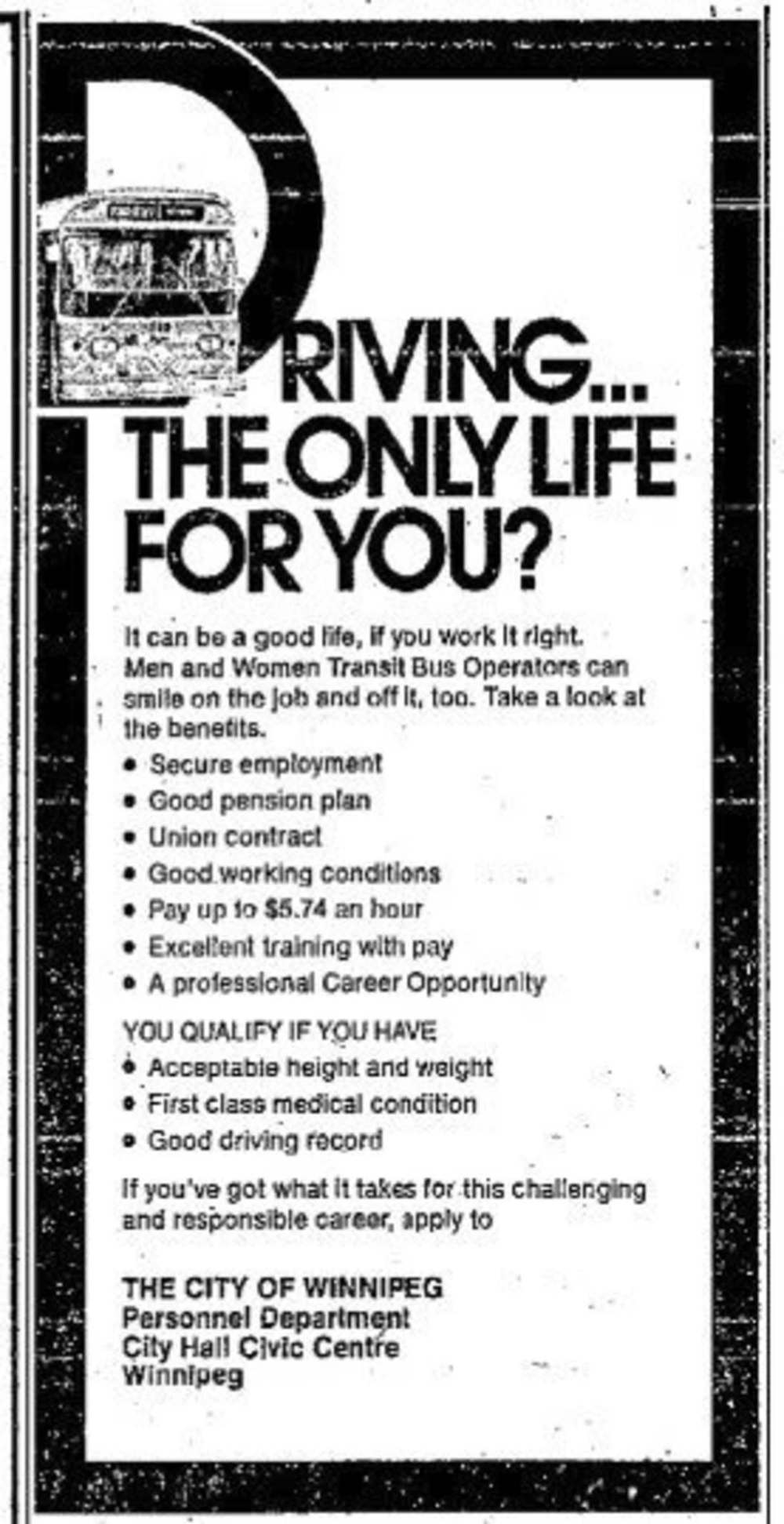

It was in November of that year a friend showed her a Winnipeg Transit ad seeking new operators — male and female — with an attractive starting wage of nearly $5 per hour.

During this period a number of Canadian transit systems were having difficulty attracting operators and were hoping an appeal to women would help fill the gap.

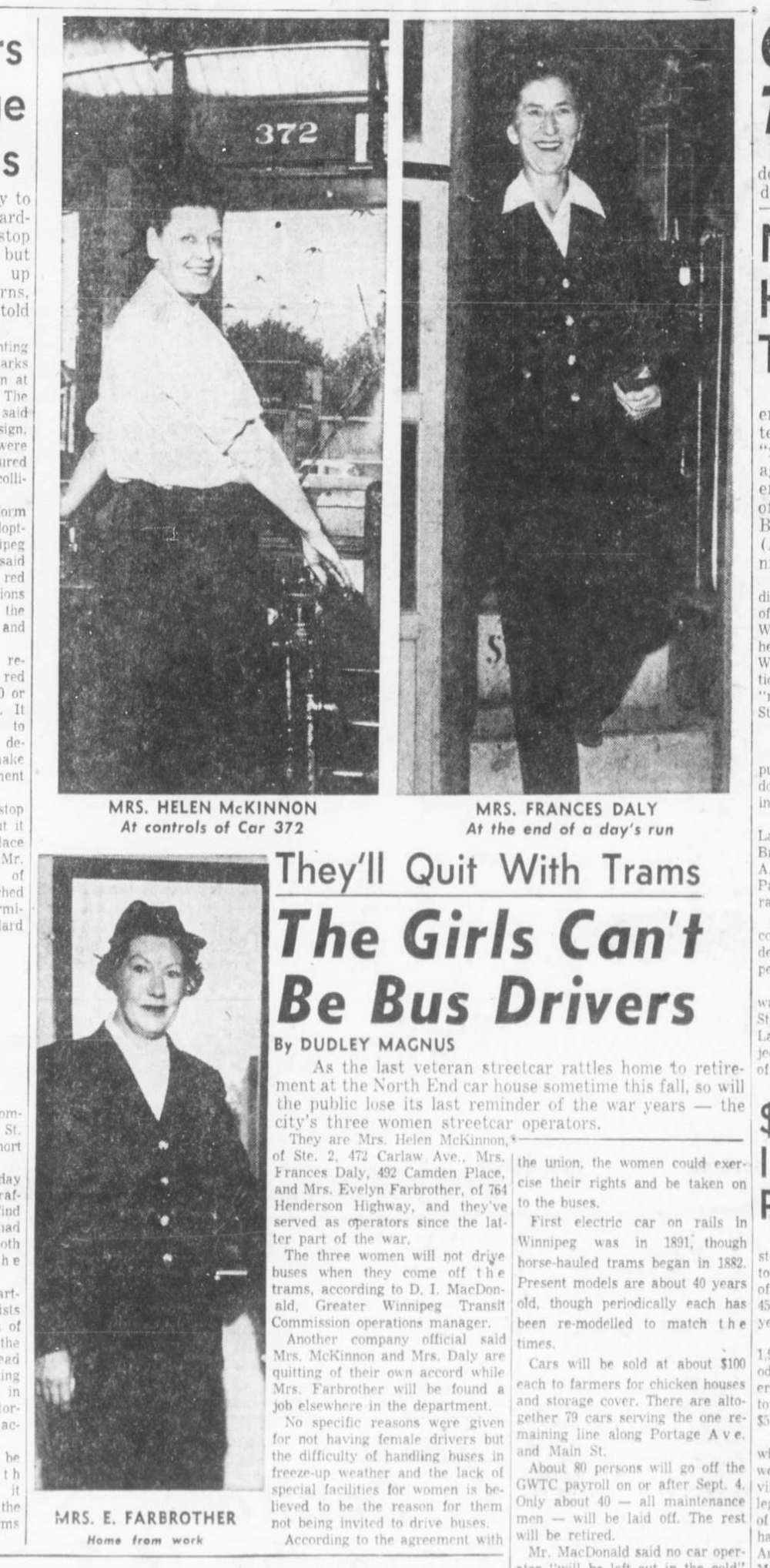

For most, there was no firm rule that said women couldn’t apply, but the height, weight and strength requirements all but precluded them.

In mid-1974, Edmonton changed its requirements to allow for female applicants and began advertising for operators in newspapers across the West, including in Brandon and Winnipeg. With another city potentially poaching local applicants, Winnipeg Transit had to quickly follow suit.

Starting in November 1974, a Winnipeg Transit applicant simply had to be tall enough to reach the floor pedals and prove they were strong enough to comfortably turn the wheel of an operating bus. A brief ad campaign including the line: “Men and women Bus Operators can smile on the job and off it, too” appeared in local newspapers.

According to media reports at the time ‘several women’ responded to Winnipeg Transit’s ad, but only Staub made it past the initial screening. She began her paid training on Nov. 25, 1974.‘The men (operators) were afraid I was going to get special privileges, but when they found out we were going to have to take the same thing, good or bad, they eased off. When I’ve had a bad day the fellas will tell me to hang in there because it gets better as it goes along’– Mary Staub in 1975 interview

Teresa Staub, Mary’s youngest child and only daughter, said the Staub children were not surprised when their mother told them she was thinking of applying to be a bus operator. “She approached us (before applying) and asked us what we thought and we said ‘go for it.’”

When asked if she thought it was an odd job choice for her mother, Teresa, who was fourteen at the time, replied, “Not if you knew my mom. My mom was so strong mentally and physically. It was unbelievable.” In fact, she says, her mother wanted to be a police officer but her grandmother dissuaded her mother by reminding her of the potential danger and the fact she had five kids who depended on her.

By the end of the year Staub had completed her five-week training course, which lasted eight hours a day, six days a week.

On Jan. 2, 1975, she was scheduled for her first solo shift.

Earlier that day Winnipeg Transit hosted a press conference at its Fort Rouge garage to introduce Staub to the public and encourage more women to apply to the department.

It was noted Mary would get the exact same shift rotations as her male counterparts and even her uniform would be the standard men’s uniform with the buttons reversed.

When Staub was asked what the reaction from passengers had been on her training runs Staub replied, “Their mouths drop open and they look really surprised …”

A reporter caught up with Staub a few months into the job to see how she was doing. She said “The job becomes easier every day and I can see myself improving.”

She admitted at first she felt self-conscious that passengers were watching her and expecting her to make a mistake, but that feeling soon disappeared when she realized she had the public’s support. Many wished her all the best when they boarded.

When the topic of sexism in the workplace was raised, Staub brushed it aside. “The men (operators) were afraid I was going to get special privileges, but when they found out we were going to have to take the same thing, good or bad, they eased off.”

She added, “When I’ve had a bad day the fellas will tell me to hang in there because it gets better as it goes along.”

The reality, though, was quite different, according to Staub’s daughter. She said there were many dark days for her mother especially in the first year of her new profession.

“I’ve never seen my mom in tears until she came home after (driving) on her own”, noting that abuse from passengers included being spat on, cursed at and even struck. She was told countless times by men and women, co-workers and passengers alike, that her place was in the home.

“Teresa said it changed the family dynamic. Instead of the strong, fiercely independent woman there to encourage and support her kids, “…the roles were turned. She needed us at that time and we were there for her. You have no idea how proud we were of her.”

Over time, as passengers and co-workers became familiar with her, some of the mistreatment ended. Staub also grew a thicker skin to deal with it. Says Teresa, “Once she got comfortable, she didn’t put up with crap from people.”

Staub operated a bus for nearly ten years and in 1985 she continued with Winnipeg Transit as a controller, then a supervisor.

Teresa, who herself had a nearly 20-year career with Winnipeg Transit — all of it behind a desk, not behind the wheel — got a chance to work with her mother for a few years. She found most saw only the “Tough Mary” persona and that “… a lot of people really didn’t know her and didn’t know what a big, kind heart she had.”

After more than four decades of hard work Mary Staub, sadly, didn’t get the chance to retire. She died of cancer on Feb. 26, 1990 at the age of 59.

The path Mary Staub opened up for women at Winnipeg Transit is one that not many women have chosen to follow.

Staub told the Free Press in 1985 that when she started, “The feeling was that we women were going to take over the role. But, after 10 years and only 30 of us, (female operators out of a total of about 1,000), we’re far from taking over.”

Today, of the approximately 1,100 Winnipeg Transit operators, 137 are women.

Christian Cassidy explores local history on his blog, West End Dumplings

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.