Dreams, Whipped The Montreal Expos' suddenly homeless top-level farm club inexplicably moved to Winnipeg Stadium from Buffalo in the middle of the 1970 season By: Mike Sawatzky Posted: Last Modified:

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/09/2017 (2653 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

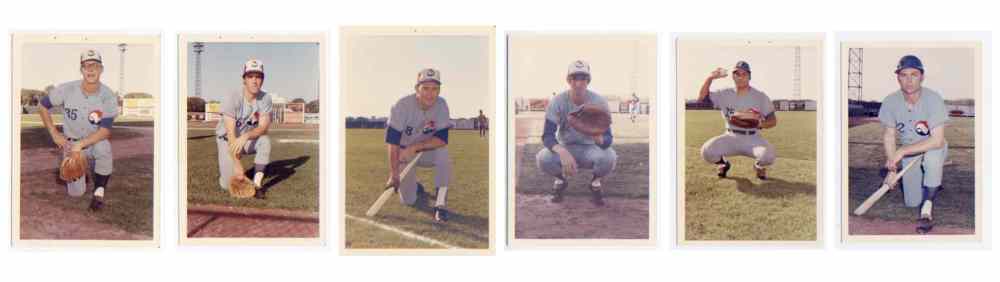

They were mostly a band of castoffs and retreads.

Many of them hoping for one more shot at the bigs, a desperate dream sparked by major league expansion that brought baseball to Montreal in the spring of 1969.

For many of them, suiting up for the International League’s Winnipeg Whips in 1970 and 1971 was a last chance.

For others like Balor Moore, then a 19-year-old pitching phenom chosen by the Expos in the first round of the 1969 draft, it was a humbling, mind-blowing experience.

Take, for instance, a conversation he had with journeyman pitcher Ron Paul in the summer of 1971. Paul had been released by the New York Mets and signed by the Expos before being assigned to the Whips, their Triple-A affiliate.

“We’re sitting in the bullpen and he says, ‘How do you know when to retire?’” Moore recalled in a recent interview with the Free Press. “‘Do they just rip the uniform off you? How do you know?’ We were all sitting in the bullpen enjoying the weather, and he had his arms behind his head.

“About that time a seagull flew over and took a crap on his left arm, his pitching arm. He looked down and says, ‘Men, that’s how you know.’ He got up and walked into the clubhouse and that was it. He ended his career based on the seagull.’ “

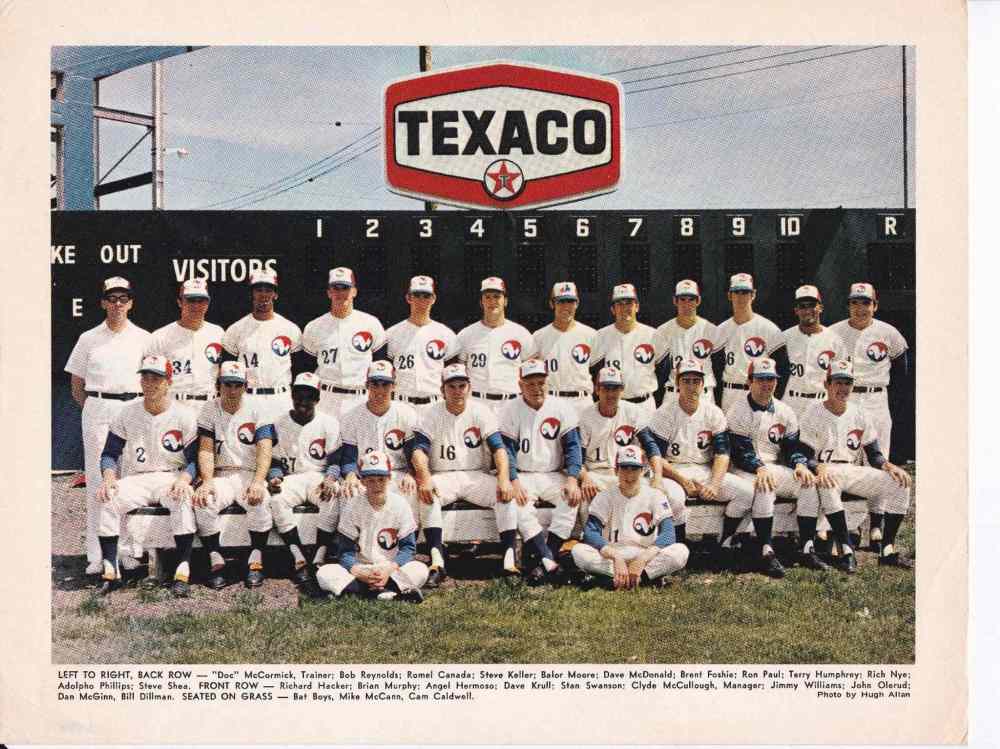

Paul was finished with baseball after going 0-2 with a 7.46 ERA in 17 appearances for the Whips. He was one of 65 players who donned the funky Whips jersey over the course of their 1 1/2-season existence. The Whips were uniformly bad, finishing last twice and going 43-59 in 1970 after relocating at mid-season from Buffalo, N.Y., and 32-58 in 1971 — their only full campaign on the Prairies.

The move to Winnipeg was so ill-conceived it seems hard to fathom now.

“Montreal was an expansion club and obviously they didn’t have all the minor-league systems set up,” says Moore.

“And so, at one point their Triple-A club was in Buffalo, N.Y., in (War) Memorial Stadium. So, I come up and join (Buffalo Bisons) team and witnessed one game there, they were playing the Richmond (Va.) Braves, the Atlanta Braves’ Triple-A club, and so after the game, the Richmond club gets on their bus and the bus goes under assault with people throwing rocks. It was a bad area, I guess.

“I didn’t know this but as they’re pulling out, they’re getting rocks (thrown) and the windows got broke out. The organization said, ‘Look, we’re not going back there,’ and so the players come to the ballpark the following day and everything’s packed up and we’re gone, but we don’t have a place to go to.”

The solution?

Well, the homeless Bisons were ordered to play their home games in Virginia, either Richmond or Tidewater both of which had teams in the International League; the location would depend on which team was on the road. If both teams were at home, the Bisons trekked north to Montreal and played at the Expos’ home, Jarry Park.

“We were basically orphaned,” says Moore. “What it came out to be was we were on a 47-day road trip and we were travelling and basically didn’t have a home. We had two buses, one for family and one for the single guys.“I see a player sittin’ there [on the bus] and he’s got a dog on his lap and he’s got a birdcage hangin’ back there… Finally, they said, ‘We’re going to Winnipeg.’”– Balor Moore

“So, one time I walked out of the clubhouse and actually walked on the family bus by mistake — didn’t know which was which — and I see a player sittin’ there and he’s got a dog on his lap and he’s got a birdcage hangin’ back there… Finally, they said, ‘We’re going to Winnipeg.’”

The transfer to Winnipeg, hinted at in the local media as early as June 6, came to fruition five days later when the Expos announced they were shipping the team to Manitoba and would play 27 home dates in 1970.

The Expos brokered a deal with Randy Moffat, owner of the Winnipeg Goldeyes of the single-A Northern League, to move his franchise to South Dakota, allowing the newly christened Whips to take up residence on a diamond in the less-than-ideal-for-baseball southwest corner of Winnipeg Stadium.

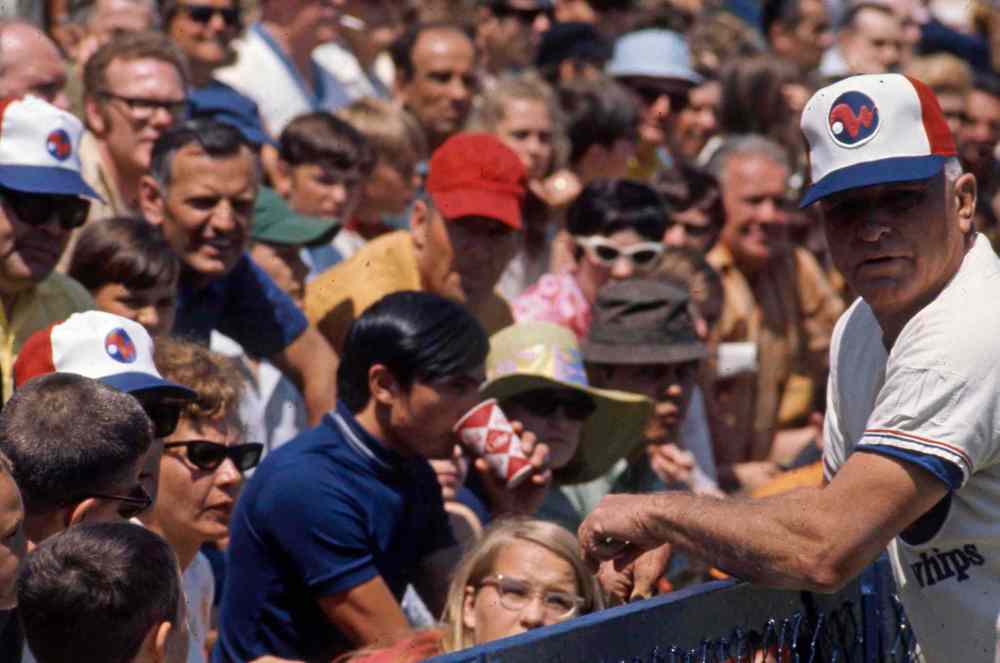

Initially, triple-A baseball was the talk of the town.

A sellout crowd of more than 7,000 showed up for the home opener on June 19 (a 5-2 victory over the Syracuse Chiefs), but weather and poor results gradually chipped away at the enthusiasm for baseball.

By 1971, the International League’s reluctance to play games in a western outpost such as Winnipeg (the closest team was 1,800 kilometres away in Toledo) was making everyone, including the Expos, nervous. By the end of that year, the Expos said they had lost $500,000 on the operation, much of it due to the cost of shuttling the teams by air. A much-talked-about move to the more geographically friendly American Association never happened.

Expos’ first-round draft pick Steve Rogers joined the Whips directly out of college in 1971 and he immediately noticed the dropoff in talent.

“(Montreal) had a decent double-A (team) but triple-A was castoffs from everywhere,” says Rogers. “With that in mind, I went from the third best team in the nation out of college and had very good senior year and was a second team all-American — so it was a good year and we had a helluva team.

“So I went there, I guarantee you, our college didn’t have the starting pitching depth to go every five days… but we would’ve beaten them in every seven-game series we played. It was really just patchwork. That was the biggest eye-opener — going there and truly being overmatched every time we walked on the field.”

Veteran pitcher Mike Wegener didn’t have a very favourable scouting report, either.

“There was some good talent there but we did not have a good hitting ball club,” says Wegener. “It wasn’t real consistent and our pitching was definitely not consistent… It might have been the worst team I ever played on, based on talent and record and everything.”

It was most definitely every man for himself.

“It was a lot of guys just hanging on, looking to try to get one last shot with Montreal — an expansion team,” says Rogers, now 67 and a special assistant for the Major League Players Association, based out of Princeton, N.J.

“Everybody was kinda in it for themselves. It was not a team situation. Everybody had an individual agenda, and rightly so… It was really just a reflection of how they had to put together a Triple-A team.”

Rogers’ time in Winnipeg was short — he left the team at mid-season to fufil an engagement with the U.S. National Guard — but he has fond memories of the city.

He met his first wife in Winnipeg and relished his visits to the Paddock Restaurant, a local landmark for “steak with all the trimmings” on Portage Avenue across from Polo Park,

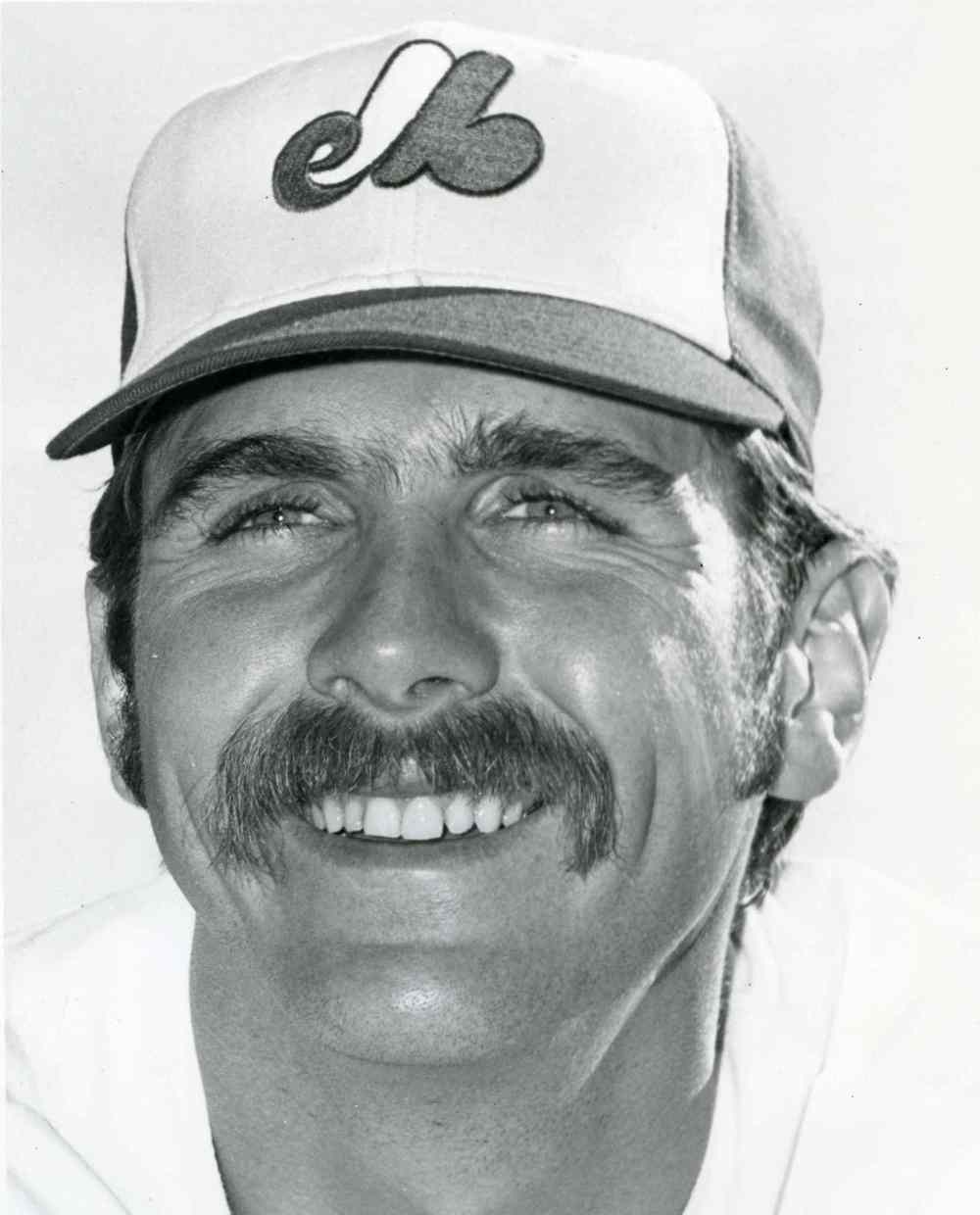

Rogers would go on to become the finest pitcher in Expos history, but he almost became a victim of overcoaching in Winnipeg.

Manager Clyde McCullough was instructed to alter his delivery, but the team relented when Rogers’ performance tanked.

“They decided the way I pitched in college — I had an unorthodox delivery — and they were going to change it,” says Rogers, who was 3-10 with a 3.97 ERA in 15 appearances with the Whips.

“By the time two months of that had happened, my arm was so screwed up. It was more the way baseball was managed. I got to meet a lot of guys who had played in the major leagues and they were pretty hardscrabble.”

The Expos often sought out reclamation projects, hoping they’d be able to revive their careers. One such case was former Detroit Tigers pitcher Joe Sparma, who was rescued from the scrap heap to join the team in 1971.

“All of a sudden he got where he couldn’t throw a strike,” says the 66-year-old Moore. “Montreal picked him up, thinking if he ever fixed his control, he still had talent.”

Once, between games of a home doubleheader, Sparma, who had played quarterback for the legendary Woody Hayes at Ohio State, was hanging out with members of the local CFL team.

“Well, the Blue Bombers were practising,” says Moore. “They had taken down the (temporary) fence and everything and Sparma recognized either (former) teammates or coaches with the Blue Bombers. The next thing you know he’s out there throwing the football and kinda messin’ around with ‘em…

“He had the locker next to me and comes in and sits down and I said, ‘God, what’s wrong?’ He said, ‘I’ve got a tough decision.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘Well, my baseball career sucks and the Blue Bombers just offered me a contract.’ He stayed with baseball but he lasted (only) about another year.”

In the end, the Whips never seemed to have a chance for survival.

On May 14, 1971, Winnipeg smashed a modern day Triple-A record of nine home runs in front of 697 fans, only to lose to visiting Syracuse. The hosts rallied from an 11-1 deficit to take a 12-11 lead with two outs in the ninth inning only to lose 15-13 in 12 innings.

Jimy Williams, who went on to manage three major league teams including the Toronto Blue Jays, was the light-hitting Whips shortstop who hit three home runs in that game. His teammates included John Olerud Sr., now a well-known dermatologist in Seattle, legendary hitting instructor Walt Hriniak and pitcher Mike Torrez.

The Winnipeggers played their final game on Sept. 2 (a 9-8 loss to Louisville Colonels) amid rumblings the league wanted to move the franchise. By November, Expos general manager Jim Fanning had pulled the plug himself, announcing the team would relocate to Lynchburg, Va., as the Peninsula Whips.

Moore, who had a successful eight-year career in the majors with minor league stops in Vancouver, Calgary and Quebec City before retiring to own and operate Brittex Pipe Co. in Houston, has a few regrets.

“It probably hurt me in the long run,” he says of beginning his career with the sad-sack Whips. “It had to do with the overall atmosphere… People who didn’t want to be there in the Expos organization and on the back side of their careers.

“I was exposed to a lot of that at 19 years old. I got conditioned to that as the way pro ball was… I should’ve been in much lower minor leagues and played with guys more my own age, with the enthusiasm of being in pro ball with a career in front of ‘em and not behind ‘em.”

Field of screams

Winnipeg Stadium had an odd configuration for baseball, with the diamond shoehorned into the southwest corner of a football practice field, and Texas native Balor Moore was shocked when he arrived for his first game in Winnipeg early in the summer of 1970.

“There wasn’t a left-field fence. There was a right-field fence and then centre-field with these giant (football) bleachers out there,” says Moore, who was the Expos’ 19-year-old lefty ace-in-waiting. “And the Blue Bombers practised there so you know, what do you do? They go out and get two-by-fours, cut ’em in half and built legs on ’em and put chicken wire across and you’ve got a left-field fence. And they put cinder blocks on each leg to keep the fence from blowing over.

“So, we get to the ballpark for the first game and the left-field fence is like 260 (feet). I said, ‘Wait, this can’t be right.’ But they went ahead and played the game like that.”

As it happened, the makeshift outfield fence was ripe for tampering.

“It got to be a game with the pitchers and the hitters and who would get to the ballpark first,” says Moore. “If the pitchers got there first, we’d pick up the fence and moved it back to about 350. If the hitters got there first, it would be back up to about 300. It got to be back and forth, it was comical.”

Steve Rogers, another first-round Expos draft pick who joined the Whips fresh out of college in 1971, said the ballpark was hardly pitcher friendly.

“I tell you, nobody could do anything about dead-centre field because it butted up right against the stadium,” says Rogers. “You couldn’t go further back, it was concrete. If I’m not mistaken, they labelled it 360 to centre field. We all said, ‘That’s bulls–t. There’s no way that’s 360 feet away from home plate.’

“We went and walked it off a number of times and it was no further than 340, 345 tops. You had no place to pitch.”

Right field, meanwhile, was downright menacing.

“They had a really sharp-edged, metal scoreboard stuck right up against that concrete wall, right in dead-right field,” says Rogers.

“I think it was a Toledo Mudhen right-fielder who went back and hit his head on the corner of the hard metal (scoreboard). It just split his head wide open – they carried him off on a stretcher. Today, nobody would’ve set foot on the field.”

Injury? What injury?

Mike Wegener took playing hurt seriously.

Signed by the Baltimore Orioles in 1964, the hard-throwing righty was drafted by the Philadelphia Phillies organization in 1965 before a serious arm injury threatened to derail his career.

Picked in the 1969 expansion draft, Wegner played two seasons with the Montreal Expos and by the time he reached Winnipeg as a 25-year-old in the summer of 1971, he had already played his final game in the bigs. But Montreal had given him hope.

“Shoot, I was elated. Here’s my chance… I pitched with a bad arm for three years and the (brass in the Phillies organization) didn’t know what I’d actually done to my arm because I tried to hide it,” says the 70-year-old Wegener, now retired and living in Geneva, Ohio.

”I knew as soon as I hurt my arm I’d be considered damaged goods and they wouldn’t want to invest any money in me. Because I tore my ulnar tendon in my right arm — snapped it — in 1966 when I was in Bakersfield, Calif. I took cortisone shots every four days – this was before Tommy John surgery.“I didn’t let anybody know how bad it was. I just kept playing, but I had to take that year off and got to the doctor. My arm used to blow up after I pitched and once it went down, then I’d get my cortisone shot for my next start and go back out there.”– Mike Wegener

“I didn’t let anybody know how bad it was. I just kept playing, but I had to take that year off and got to the doctor. My arm used to blow up after I pitched and once it went down, then I’d get my cortisone shot for my next start and go back out there. But guys wouldn’t do that today.

“In fact, when I signed with the Orioles in 1964 right out of high school, my dad had to co-sign for me because I was only 17. I was very immature. I was a good athlete, but I was immature in a lot of different ways. You talk about growing up quick – you either grow up or get out.”

Wegener says he was administered cortisone shots from 1966 to ’68 before finally getting corrective surgery during his first season in the big leagues. But his arm was never the same. He was 3-11 with a 4.89 ERA in 103 innings with the Whips.

“It was in good shape but I didn’t have the stamina I once had,” he says. “I could still throw 98, 99 (m.p.h.), you know. I just couldn’t maintain it for nine innings. When I signed, they expected you to pitch nine innings.”

He considers a 15-strikeout, 11-inning no-decision in which he gave up only two runs to the New York Mets on Sept. 10, 1969, to be a career highlight.

Wegener retired from baseball following the 1977 season. He moved on to the next stage of his life as an employee of the U.S. Department of Defence, where he served as a quality engineer for the production of triggers for nuclear weapons at the government’s production facility in Rocky Flats, Colo.

mike.sawatzky@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @sawa14

Mike Sawatzky

Reporter

Mike has been working on the Free Press sports desk since 2003.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.