Knight in thrift-store armour

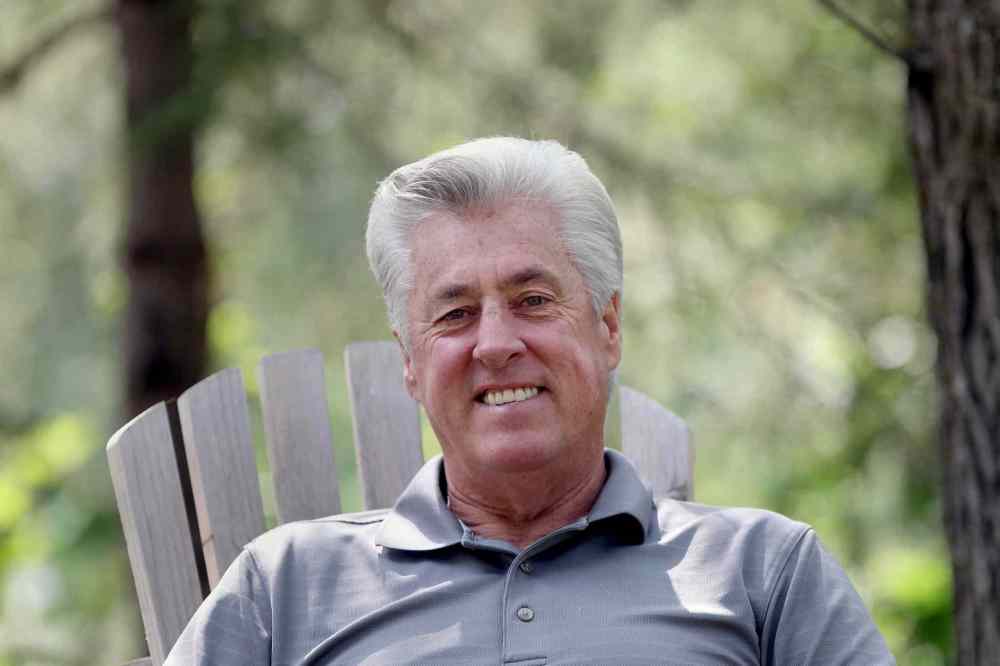

Defeat is not an option for Sel Burrows, the patron saint of Point Douglas

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/09/2017 (3022 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 2007, Sel Burrows, a cat-loving hippie, heard a loud ruckus outside his home on Grove Street in North Point Douglas.

He quickly realized that a member of the Crazy Eights street gang was threatening the son of one of his neighbours.

Turns out, the neighbour’s kid wanted to extricate himself from the gang, so the member, around 16, had dropped by to issue an ultimatum: we’ll burn your house and kill your little dog, too.

Well, this would not stand for Burrows, all 5-foot-7 and about 140 pounds of him.

So Burrows, then 64, sprints outside to confront the young gangster. He’s carrying some cheap camera. Recalls Burrows: “I stupidly came out with a little digital camera and said I was going to take pictures of him.”

Not surprisingly, the gang member didn’t seemed fazed by a undersized senior citizen. He ripped the camera out of Burrows hands and jumped on his bike to speed off. Burrows reached out and grabbed the kid by the scruff of his neck and, due to the momentum of the bike, flipped the teenager off the bike and onto the ground.

Now we’ve got a problem. The gang member is much larger than Burrows and much more angry.

“Well, he (the gang member) comes up with a haymaker and hits me in the eye,” Burrows says. “And he’s a big kid.”

The force of the punch shattered Burrows’ eye socket. More gang members arrived on the scene. Burrows is down to one good eye and a prayer.

“So I’ve got my eyeball literally hanging out,” Burrows continues. “My wife’s on the phone with 911. But the ambulance won’t come until the police come. And about 15 of the Crazy Eights have surrounded us.

“Eventually the police come and arrest the guy. And we figure, ‘Great’. But (the officers) jump out of their car, grab the kid by the hair, throw him down on the ground and do a high knee jump onto his back.

“They kicked the shit out of him.”

Fair to say, at this point, that most folks who’ve just suffered serious injury from assault would not object strenuously to their attacker being manhandled by police.

Burrows isn’t most people. In fact, he yelled at the cops. “What are you doing? There’s no need for this!”

All while trying to hold his loose eyeball in place. Because, you know, it’s the principle of the matter.

One of Burrows’ many admirers calls the story a “perfect description of how he (Burrows) is wired.”

“He’s fearless, he really is,” the acquaintance says. “And he’s not afraid of offending anybody. He’ll speak his mind to anyone. He’s fiery, but in a respectful way. But he’s got a caring inside of him that’s really extraordinary.”

Burrows meticulously tends the garden in his modest home’s yard. He makes his own wine and buys his clothes from Salvation Army thrift stores.

Oh, the aforementioned admirer? Well, that’s Mark Chipman, owner of the city’s National Hockey League team.

The first thing to know about Selwyn Burrows is that he’s not a North End lifer. He didn’t move into North Point Douglas until 2006, and his introduction to the area was ominous.

On Day 1, someone threw a giant rock at the front window of the home across the street, which Burrows soon came to discover was a crack and meth den occupied by prostitutes and other addicts.

At the time, Point Douglas was littered with such places. There were dozens of crack houses in a several-block radius. Hell, there were four on Grove Street alone. Random acts of violence, robberies and gang-turf wars were the norm.

“Each crack house was a crime centre and affected the blocks on either side of them,” Burrows explains.

The vast majority of law-abiding residents felt helpless. They didn’t trust the cops and they feared the dealers.

But Burrows isn’t just the average concerned citizen. He knows people. Back in the day, he was the executive assistant for then-premier Ed Schreyer. He was a former social worker. A provincial NDP organizer. A community development worker. A corrections official.

He’s fluent with public policy, municipal bylaws and how the government sausage is made. In short, he knew what buttons to push on both a telephone and a politician.

Burrows was also indoctrinated with an early understanding of social disparity. He was raised on Lanark Street in River Heights. His father, John Arthur, was born to wealth. His family arrived at their farm in Saskatchewan with a cook, butler and maid on a private rail car. Within just four years, however, Burrows’ grandfather had lost everything due to drought, rust and “incompetence” (Burrows’ word).

His mother, Bessie Lawrie Leckie, was the daughter of Scottish serfs.

Both parents were heavily involved in community groups, and their son Sel learned about social justice at the United Church Sunday school.

“I grew up in a home where racist words were just not acceptable,” Burrows says. “Out of this came a sense of what’s decent, proper behaviour.”

His father took him to deliver Christmas hampers in the 1940s, and seeing five kids sharing one room had an impact.

“From a very early age I saw that I lived a life of privilege,” he says.

Fast-forward almost 70 years later, and the man who arrived in North Point Douglas was a well-organized, well-connected social warrior who has no patience for “we’ll get back to you on that.”

Sel and wife Chris picked the neighbourhood largely because of affordability; they bought a three-bedroom fixer-upper for $34,000. (Sel had retired at age 48 and “hadn’t earned a penny on a job since.” Hence the frugality.

Besides, she had been smitten by North Point Douglas two decades earlier, when the couple had stuffed mailboxes in the area with political pamphlets.

“I thought, ‘What a beautiful place this is,’” she says.

In 2008, spurred by concerns from parents, Burrows and Chris — a former kindergarten teacher — along with Indigenous elder and activist Sandra Dzedzora, decided to organize a rally to make Point Douglas a “crack-free zone.”

Dzedzora says there were five crack houses on her Lorne Street block alone.

“We thought, ‘You’re not going to drive us out, we’ll drive you out,’” she says.

Their research identified the provincial Safer Communities and Neighbourhoods Act, a 2001 little-used piece of legislation that holds owners accountable for threatening or disturbing activities that regularly take place on their property, resulting in evictions and possible property closures. The law was the first of its kind in Canada, providing law-abiding Manitobans with an effective weapon in their battles to reclaim deteriorating neighbourhoods.

Five houses identified by Burrows and Co. were closed in short order. Sure enough, other residents took notice and soon were calling them with information on crack houses on their blocks.

Chris Burrows suggested the informal group started by the trio be called Point Powerline. They distributed a flyer throughout Point Douglas with their home number and email on it.

“We were inundated with calls,” Sel Burrows says. “We discovered there was a huge pent-up energy of people living here who wanted to live in a better community, they just didn’t know what to do. As soon as people felt there was some hope, then they started to phone us. Stuff happened.”

He doesn’t have to look very far for symbols of change. When he first moved into the area, there was a rooming house across the street populated by drug traffickers and their customers. It was, at one time, the Winnipeg address most visited by police.

Burrows found out when the building’s annual business licence would expire and put pressure on the city not to renew it. The owner (based in Vancouver) sold the house to a Winnipeg investor who renovated; the former trouble spot is now a duplex where two families live.

“This is an example of the change in Point Douglas,” he says, “from the very worst to the very best.”

He estimates that with the assistance of community, more than 200 crack houses have been shuttered in last decade. There are only four left, he said, and the occupants of two of them are in the process of being evicted.

“It’s night and day,” he says. “Ten years ago the bad guys ran Point Douglas and the good guys hid. Now the bad guys hide. The crime side of it now is so small compared to when we started… we consider that part just about over. We’ve won.

“The bad guys are on the run in Point Douglas. They really are. The cops actually ask guys when they set up in Point Douglas, ‘Are you stupid? In Point Douglas the neighbours call us.’”

Still, even if the number of crack houses in Point Douglas has decreased dramatically, the violence fed by drugs and poverty remains. One man died and another woman was critically injured during a stabbing attack in a home on Euclid Avenue in July. That same month two others were killed in a rooming-house fire on Austin Street that police are investigating as an arson.“If you spend some time with Sel you know he’s like a dog on a bone. Sel forces you, in a good way, not to let things go… Even if you don’t want to deal with him, you’re forced to deal with him. That’s a good thing.”

Which brings us to Burrows’ next initiative, starting in September, to make Point Douglas a “violence-free zone” — spousal abuse and random assaults, in particular.

Burrows points to a recent incident where a man was found badly beaten in a rooming house where he was meeting a prostitute. When police arrived, the victim walked away without giving a statement. Burrows calls it a “culture of fear.”

“This happens time and time and time again where people don’t want to press charges,” he says.

Another of Burrows’ big-picture objectives involves inner-city school absenteeism. He has pleaded with school administrators to address the issue for years, to no avail.

Finally, he asked the Winnipeg School Division to provide the number of absentee students at Kelvin High School, located in Crescentwood, on a random day (he picked May 30, 2016) and compare the number on the same day at St. Johns High School, at Church Avenue and Powers Street in the North End.

Dull moments amid the drama

Since starting Point Powerline eight years ago, Sel Burrows and his wife Chris have fielded thousands of phone calls at all hours, ranging from emergencies to mundane complaints. For Burrows, it’s all in a day’s work.

“It’s very satisfying when someone lets you know about a problem and we are able to solve it,” he says.

Burrows says the most interesting call to date was from a grandmother who asked the couple to come and pick up her grandson’s stash of crack cocaine.

“She didn’t want him selling crack or having crack in the house but she didn’t want to turn him in to the police,” Burrows explains.

“Chris and I went over to the house to pick up the several hits of crack when we realized we might be stopped by police. We phoned 911 and told them we were bringing crack into the police station to turn it in.”

Burrows said the young constable at the front desk was perplexed “but eventually accepted the crack and gave us a receipt.”

Here’s Burrows’ account of a day in his life and calls to the Point Powerline:

• Backyard campfire not in proper fire pit.

• Garbage dumped behind neighbour’s house. Notify 311.

• Landlord cleaning up after arrest Burrows had arranged put hundreds of needles in blue recycling bin. Neighbours upset. Emailed 311.

• Guy calls to say he was held up with gun but won’t say where. Very frustrating. Sandy (Dzedzora) talked to him, think we have address. Will discuss with police tomorrow.

• Rooming house without hot water for days. Contacted owner, he fixed it.

• Landlord calls regarding suspicions over tenant dealing drugs. Confirm it is his tenant’s mother.

• Person evicted moves in on mentally ill neighbour. Contact WRHA supervisor to get mental-health worker to protect his client. (No confidentiality in inner city)

• Played tennis.

• Drunk woman lying in our garden. Called 911.

• Talked to landlord about evicting meth dealer. She remains nervous.

• Emailed Manitoba Housing regarding four-bedroom house with only two adults who are having out-of-control parties.

• Picked up son from ER after kidney-stone attack.

• Time for a glass of homemade red wine.

There were 38 students absent at Kelvin and 161 at St. Johns.

Not long after, Education Minister Ian Wishart was sitting in Burrows’ living room, along with senior assistant deputy minister Rob Santos, to discuss putting together an action group to develop methods to keep students in classrooms. Burrows is confident those policies-in-progress will soon become realities.

“I was amazed when he (Wishart) agreed to meet with me. In shock, actually, since he knew my (NDP) political affiliation. People have suggested that the Tories were using me. My response was if more kids end up going to school, who cares?”

But perhaps Burrows’ biggest challenge — before taking aim at crack houses, derelict properties and truancy — was building a bridge with the men and women in blue.

In the early days, Burrows says, when his phone would ring, “We got almost as many calls about police misbehaviour as we did about crime.”

“In the inner city, the relationship between the cops and the people of the community 10 years ago was really ugly,” he says. “Even the good people hated the cops, from their behaviour.”

It wasn’t long before former police chief Keith McCaskill would be sitting in Burrows’ living room, too. Or the district division commander. Word spread quickly from top brass within the Winnipeg Police Service that if any suspects were unduly restrained or abused, the wrath of Burrows would be incurred. And wrath runs downhill.

In the last six years, Burrows has received only two calls related to police behaviour. Conversely, he has urged area residents to be more trusting of the men and woman walking the beat in Point Douglas.

“We look at Sel as sort of a broker for us,” says Insp. Jamie Blunden, the District 3 commander. “Sometimes there’s that reluctance to have trust with us right off the bat because they don’t know us as individuals. If Sel’s talking to us… then those barriers start to get broken down.

“If you spend some time with Sel you know he’s like a dog on a bone. Sel forces you, in a good way, not to let things go. That allows us to get involved with that community. He knows everything that’s going on. He knows the problem houses, he knows the problem people,” Blunden says.

“Even if you don’t want to deal with him, you’re forced to deal with him. That’s a good thing.

“Let’s face it, we know some people — and our service isn’t any different — if they can give you some lip service and walk away thinking you’ve done the job, some guys will try to get away with that… (Burrows) holds people accountable and he expects things to be done.”

Burrows can come across as abrasive to some. He doesn’t apologize. Remember that effort to make North Point Douglas a crack-free zone? A couple of members of the residents’ committee felt it would make addicts feel under attack.

“This small item outlines a communication problem that what I call ‘American liberals’ have in the inner city,” Burrows says. “By trying to be so accurate and correct, they are unable to communicate. Most people in the inner city are very blunt. They use strong language, which is not always appreciated by middle-class folk.”

Longtime ally and former Point Douglas MLA Kevin Chief says Burrows is focused on the task at hand.

“He’s not always trying to be diplomatic, he’s trying to make a difference,” Chief says. “And if that means being more direct, he’ll be more direct. But at the end of the day he just wants results.”

Does Burrows have some sort of unique skill he uses to make the powers that be miserable?

The former police chief chuckles.

“Sel is a very opinionated guy,” McCaskill says. “He would certainly phone, if he was upset about certain things, and want things done now. How do I put Sel? He’s obstinate, for sure. Even with the issue of him confronting drug dealers, I’d joked with him, ‘If you get hurt I’m going to kick your butt.’ He would laugh.

“I would suggest that if you met him in a certain situation where he was trying to get something done you might say, ‘Wait a second, I’m not sure if this is a guy I want to hang with.’ But when you start getting to know him he’s a really great guy. He wants to change things. That’s Sel.”

And if that means standing up to politicians or cops — or drug dealers — so be it.

“Nobody’s going to f—ing intimidate me. No way,” Burrows says when asked about the potential of physical threats. “Oh, we’ve had rocks through the window. We’ve had tires slashed.

“My personal belief system is you’re safer when you go into somebody’s face than you are if you run from it. And it’s proven to be true. The cops have told me, ‘don’t do this stuff.’ But, hey, 11 years later… one incident.”

About that incident: you’d never know there are five tiny screws holding a piece of Teflon that helps keep his eyeball in place.

In addition to Sel and Chris, the Grove Street house is now occupied by two grandchildren, three cats and two dogs.

The walls are lined with art, mostly Indigenous masks, that the couple have collected on their many excursions to Mexico and Central America. There is the garden in the back and another on the boulevard, just a stone’s throw from the Red River, which is a great source of pride.

The couple raised three children; daughters Teresa (an artist) and Karen (a federal parole officer) and son Riel Dylan (provincial bridge repair supervisor), who was named after a rebel and a Welsh poet, and now lives just down Grove.

For the last decade, their home has been a meeting place, a refuge and the North End’s version of a 311 and 911 call centre.

It was not uncommon, a few years ago, to field 10 to 15 calls a day from residents reporting grievances, emergencies and family disputes. In fact, the phone rings while a Free Press reporter and photographer are visiting. Chris takes the call; a neighbour is having a problem with his grandchildren, fearing they and their mother are using meth. He wants Burrows to help find assistance from a government agency.

“Sel will hunt it down and figure out what to do,” Chris says.

She has been slowed by illness, which keeps her husband closer to home. During an interview, she is lying on her bed with a calico cat named Picasso.

“He’s going to make himself heard,” she says of Sel. “And if he thinks something’s unfair he’ll shed light on it. He’s not all afraid of what people would think of him. Well, unless they thought he was a lazy bum lying on the beach.”

Sure, great. But fielding calls at all hours of the day?

“It’s been 47 years living with him,” she says with a smile. “So I’ve almost forgotten what anything else was like.

“I think people should put their nose in and take more notice of what’s going on around them. It might be better. I hope wherever my kids are living they can turn to their neighbours. There’s far too much secretiveness in the world; everybody guarding their confidentiality. I think we’d all be better off if people paid more attention to their neighbours, but in a good way.”

But it hasn’t been all about violence and drugs. It has, largely, been about building, bridging and beautifying.

When a handful of prominent Winnipeg businessmen, led by Mark and Steve Chipman, planned to open a private, independent Jesuit school in the heart of Point Douglas, Burrows was an early advocate. But not until Burrows was convinced that the reconciliation project — designed to funnel graduates to St. Paul’s High School and St. Mary’s Academy tuition-free — was in the community’s best interests.

The Gonzaga Middle School opened last year with 20 students, with plans to eventually expand to 60 from grades 6 to 8.

“I see him more as a wealth of wisdom more than a guy you need to appease,” Mark Chipman says. “Sure, you’d like him to approve what you’re doing, but he’s been more of a resource for us. He’s got a knowledge of that part of the city that I don’t think anybody else possesses.

“He’s a remarkable man. He’s got well-earned and a lot of established connections with people in this city. From politics and business and social services. He knows a lot of people.”

A few months ago, Burrows got it in his head that the underpass at Main Street and Higgins Avenue needed to be brightly painted and have improved lighting installed.

He was informed by local CP Rail officials that they had no authority for approval.

Burrows wanted to know who did. The CP Rail people told him it was the company’s Western Canada executive. So Burrows contacted Chipman to ask whether he knew whoever that was. Chipman didn’t, but promised to find out.

Long story short: The underpass has been painted white. New lighting has been installed. The North Point Douglas residents’ committee secured funding from Downtown Biz ($1,500), North End Biz ($300) and Assiniboine Credit Union ($500), while several local organizations volunteered to paint.

“So, basically, two things have happened: One is the place is a lot nicer, and a bunch of inner-city people feel proud that they’ve done something themselves,” Burrows reasons.

Indeed, one of Burrows’ core tenets is solutions should come from the community.

Chief, now vice-president of the Business Council of Manitoba, first met Burrows in the early 2000s when he was executive director of the Winnipeg Aboriginal Sports Achievement Centre. One of the first projects they worked on together was Run With the Chiefs, a now-annual event where hundreds of inner-city schoolkids join the police chief in a three-kilometre run through Point Douglas.

“(Burrows) always worked to make the communities he’s lived in, and cares about so deeply, safer,” Chief says. “The fundamental reason I’ve learned why that’s so important to him is because he wants people to feel proud of who they are, and part of that is making sure you’re proud of where you live. And if you want to be proud of where you live, you have to feel safe.

“You have to feel that you’re contributing back to your neighborhood. He built confidence in me. He made me feel really good about the work I was doing. He said, ‘The work you’re doing is important. How can I help?’

“There’s nothing too small or too big he won’t take on. He’s showing, along with so many other seniors, the direct impact that you can make on dealing with some of the toughest issues our city is facing.”

It’s important to stress that Burrows is not, and never has been, a one-man operation. Far from it, in fact, and Burrows will be the first to tell you he’s had tons of help, the bulk of it from senior citizens.

For example, Dzedzora, 73, was instrumental in the project to restore Barber House and transform the Euclid Avenue heritage building into the area seniors centre. Dzedzora also spearheaded efforts to open the Eagle Wing Early Education Centre and was a founding member of Sistars, a grassroots community organization started by 16 women.

While Dzedzora might be a workhorse, she has a name for Burrows’ spirit animal.

“Sel Burrows is my pitbull,” she says. “Anytime I’ve run into something where I can’t push through, I’ll call him. Once he gets ahold of something he doesn’t let go. It’s hard to describe the effect he’s had. He can really tough it out. He never gives up.”

Dzedzora has called Point Douglas home since 1984. She says Burrows has helped instil a determination among residents, young and old, to fight for their neighbourhood.

“There’s no such thing in our vocabulary as backing off,” she insists. “We love our community. It’s been worth every bit of fight to where it is today. It’s been a real challenge, but I love the neighbourhood now.

“Sure, there are difficulties, but not at all to the extreme they were. Not even close.”

The secret of Sel’s success turns out to be nothing particularly revolutionary. He’s not a rebel. He’s a resident who has worked to ensure the institutions responsible for protecting his community do just that.

In other words, insist the people working in those government departments and services do their jobs.

And he has more in his toolbox than just that 2001 provincial law. The city’s Neighbourhood Liveability bylaw — a wide-ranging ordinance that sets standards for everything from noise to yard maintenance to garbage to derelict homes — has been particularly useful.

The North Point Douglas residents’ committee used to complain to city officials constantly about problem properties, but got almost no results. So a few years back, Burrows got six neighbours to call the city bylaw enforcement office to complain about “an ugly, derelict house.”

When Burrows was finally able to speak with a city official, he was told the home was “perfectly acceptable for the neighbourhood.”

Wrong answer. The pitbull was off the leash now.

“I said, ‘wow, thank you.’ He said, ‘What do you mean?’” Burrows gleefully recalls. “I said, ‘You’ve just given me the title of my speech to city council. And YOU’RE going to be there. And we’re going to have 8 x 11 colour photos.’ And we did. The councillors were furious.”

Today, members of the city’s bylaw enforcement department work with residents’ committee. They tour the area together to identify trouble spots.

“Some city and provincial officials feel threatened and see him as a pest, but to me he’s the people’s agitator,” says Gord Mackintosh, who served as MLA for St. Johns (which borders Point Douglas) from 1993 to 2016. “He proved that laws do make a difference, but only if folks know about them (and) speak up, and government responds. And he made government respond.

“Sel moved into Point Douglas and he saw the North End’s great spirit and soul, and potential, but for a few bad actors who weren’t held to account. He basically went about setting standards using existing laws and engaging residents to make officials do the job they were hired to do.”

Genius, right?

Perhaps that’s the reason that even the people Burrows challenges the most have so much respect for him.

You see, Blunden is a police inspector now, but in the mid-1990s he was a beat constable in the North End.

“Now that I’m back 20 years later, I’m saying, ‘Man, that place has changed quite a bit,” he says. “Everybody’s taking pride in that neighbourhood. There’s beautiful houses and people taking ownership.

“You go walk around there now and see the cut grass, the painted houses. So when something pops up out of the ordinary, or attracting some of the crime element, (residents) are all over it.”

Blunden is a regular visitor at the Burrows home. They’ll have coffee while Sel presents a list of concerns. Together, they negotiate priorities, given limited resources.

So Blunden has heard all about the flowers in Sel and Chris’s gardens, along with the cats and dogs underfoot.“The guy has done nothing but advocate for his area. He’s the tip of the spear.”

“That speaks to Sel’s character and personality,” Blunden says. “He looks after the neighbourhood. He looks after the people. He’s passionate about them. He cares about them. And you look at his garden and his animals. He’s a caring individual.

“The guy has done nothing but advocate for his area. He’s the tip of the spear. If you need someone to champion (an issue) and stand up — you get the followers, but some people don’t want to be out front — he’s the guy out front taking responsibility.

“If we had more Sels out there in other areas… there would probably be a decline in crime and a lot more ownership of the neighbourhood.”

If only we had more Sels. Mackintosh says the exact same thing. He’d like, say… 10, please.

“He’s my hero,” the province’s former attorney general says.

“He’s transformed Point Douglas, not just with ideas, but real action. He’s a very special Manitoban. Remember, he does this from his heart. This is volunteer effort extraordinaire that we’re witnessing. He’s one of the most amazing people I’ve ever met in all my years in public service.

“I’ve gone around the community with Sel. And it struck me as I left that he was like the MP, MLA, councillor, priest, CFS worker and cop rolled into one. He knew who lived where, what they were up to, what had to be done next.”

And for Burrows, there will always be that next thing. Although he concedes that — about to turn 75, caring for an ailing wife — he’s begun to work more closely with younger community leaders. Pitbull puppies.

“Other people are picking it up,” Burrows says. “And the demand isn’t anywhere near the same (as a decade ago). When I started, we were out (on night calls) in our pajamas.”

Still, he persists.“He was like the MP, MLA, councillor, priest, CFS worker and cop rolled into one. He knew who lived where, what they were up to, what had to be done next.”

“What we’ve been trying to say to people for a long time is if you want healthy inner-city communities you’ve got to make it safer for people,” he reasons. “If it’s not safe, people who get their acts together, they’re going to get out.

“It’s similar with the schools. People who want to get a good education for their kids are going to move. And if you lose your positive people it’s very hard to have a positive community.

“It’s a balance,” he adds. “I’ve always maintained that even though the inner city has a very high crime rate… 85-90 per cent of the people are honest. They may be poor, but they’re not criminal. But the five or 10 per cent that are criminal run things, or at least they used to in our area. Obviously there’s still a lot of crime, but they don’t run things.

“And if we’re going to be successful we have to involve the real people who live there. You can’t hire enough social workers to deal with these issues.”

It’s why Burrows and his wife are anchored on Grove Street.

“Oh, it’s home,” he says, of Point Douglas. “You can’t believe the sense of being where I should be. I can afford to live here. I have people who I really care about who care about me. Friends. And I can be useful. And for some reason being useful is important to me.”

But, hey, it’s not as though Burrows’ work isn’t recognized. On July 13, the Point Douglas Pitbull received the Order of Manitoba, the province’s highest honour, in a posh ceremony at the Legislative Building.

So it came to be that the regal Lt.-Gov. Janice Filmon rose to drape the prized medallion around the neck of a man wearing a second-hand suit purchased from Salvation Army for $17.50.

Twitter: @randyturner15

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.