In praise of Peguis

The signing of the Selkirk Treaty 200 years ago helped shape the West

By: Alexandra Paul Posted: Last Modified: | UpdatesAdvertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/07/2017 (3077 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

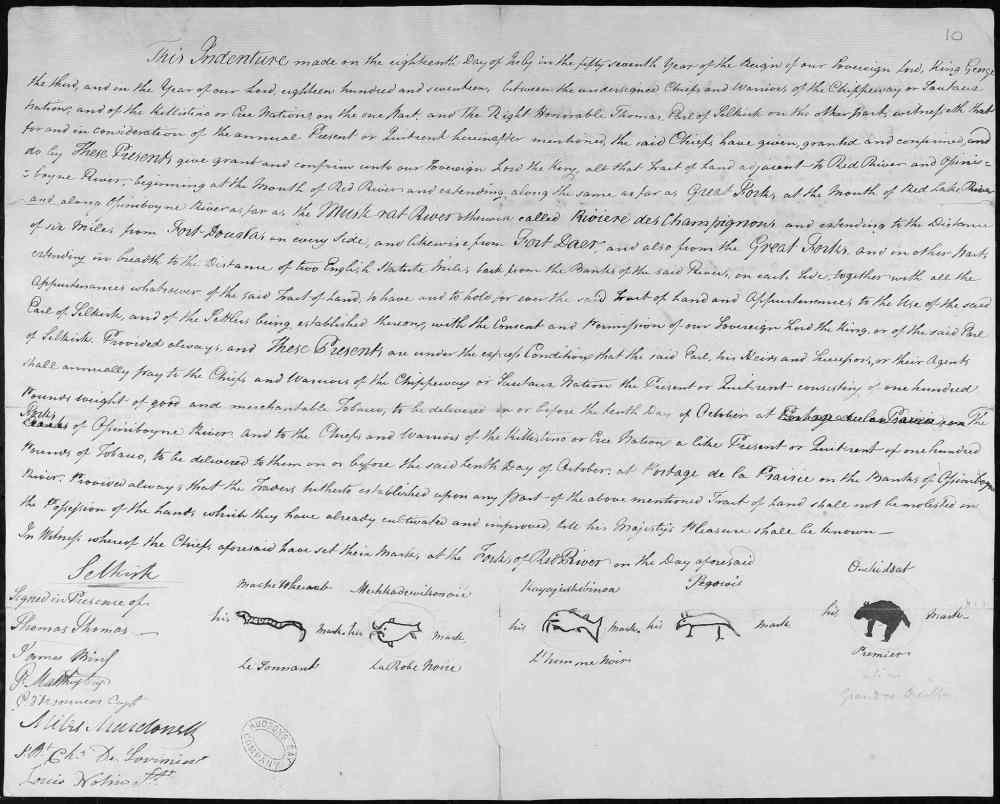

Two-and-a-half pages. Eighteenth-century legal paper, likely “borrowed” from a fur-trade ledger, the kind Hudson’s Bay Co. forts had to record accounts.

The pages are yellowing with age, covered margin to margin with spidery calligraphy, ink faded to sepia. All the hallmarks of an historical document are here.

This is the Selkirk Treaty.

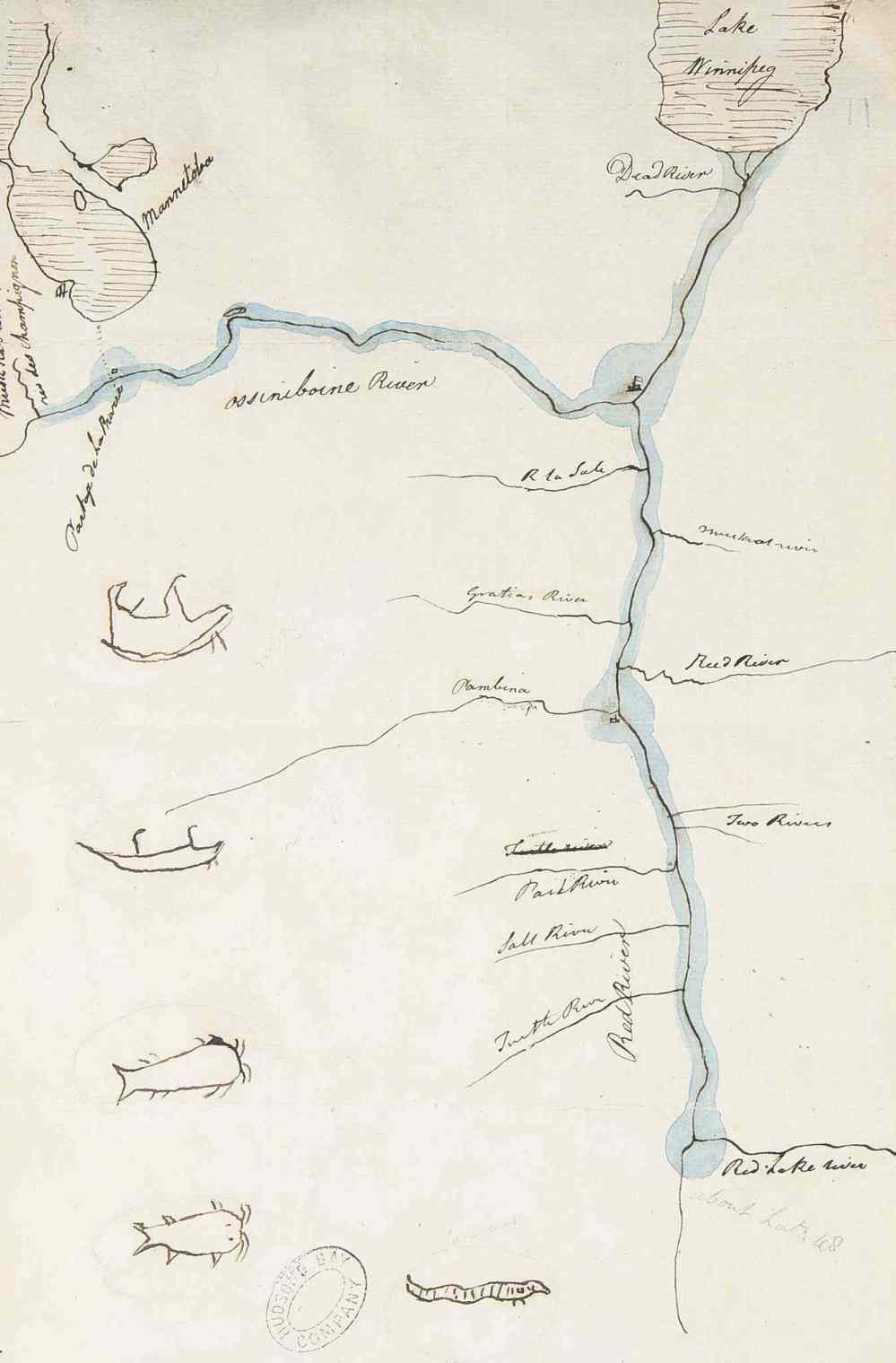

Attached is an ink map of the Red River, from Lake Winnipeg to Red Lake River to the south. It depicts a dozen little rivers swimming out like tadpole tails.

The biggest, of course, is the Assiniboine River, running west until it fades into the bottom of a fat fish, a drawing labelled Lake Manitoba.

Lined up on the margin is a puzzling row of animal graphics.

Even today, people can’t figure them all out. A bear, for sure. A catfish or two. Something that might be a salamander. Something that might be a wolf, or a marten.

The whole thing looks like it was done in a hurry, which it probably was.

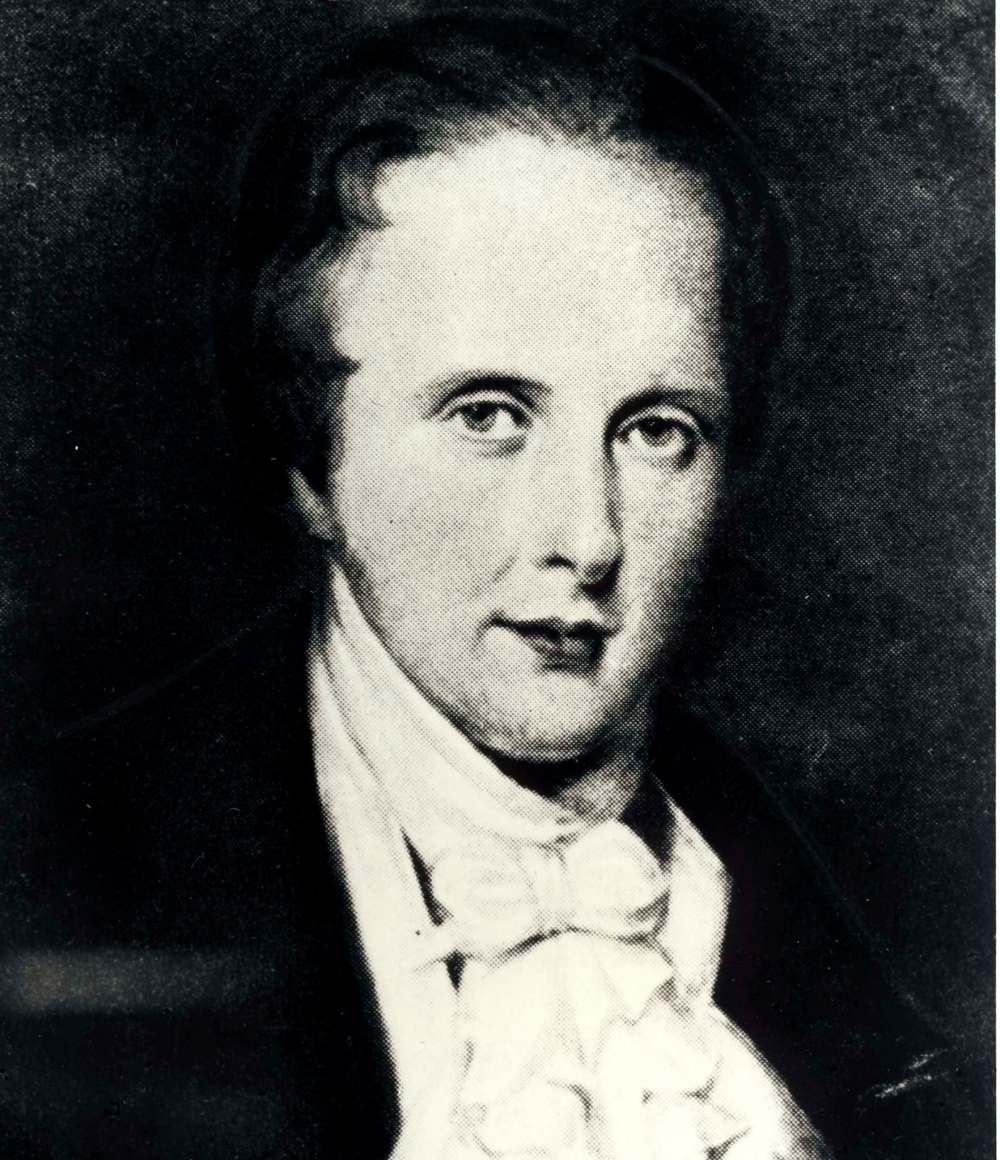

Thomas Douglas, the fifth Earl of Selkirk and founder and financier of the Red River Colony, was desperate to end the fur-trade skirmishes and outright warfare that had burned and chased out his dispossessed Highland Settlers not once, but twice, in the five years before.

He’d long had the idea of making an end-run around the fractious North West Company and dealing directly with the First Nations, asking for a “gift” of land to his people. He got his chance in 1817 on the Red River. He was there; five chiefs led by Chief Peguis were there, too.

Lord Selkirk seized the moment.

So if the treaty looks a little cramped, for lack of paper maybe it was, and maybe it was written up in a single morning and signed that same afternoon.

For one of the most important and certainly singular documents in the history of Western Canada, the Selkirk Treaty holds a lot of intriguing elements, not the least of which is it has been ignored, almost on purpose by government policy since 1867’s Confederation.

That’s despite a reluctant nod of recognition in 1871 the document was indeed a kind of treaty, even though it wasn’t signed under the Crown.

There’s no surrender of anyone’s rights in these yellowed pages, so markedly different from the numbered treaties that followed it, where all of Western Canada was described as “ceded and surrendered.”

There’s also no 49th parallel to mark the boundary between Canada and the United States because the former didn’t exist at the time and the latter not this far west in 1817.

More stuff is missing. No fancy vellum parchment. No royal signatures. No heraldic shields. No official seals in lumpy crimson wax to give it that official feel.

Selkirk Treaty is the official name, but today many call it the Peguis Selkirk Treaty.

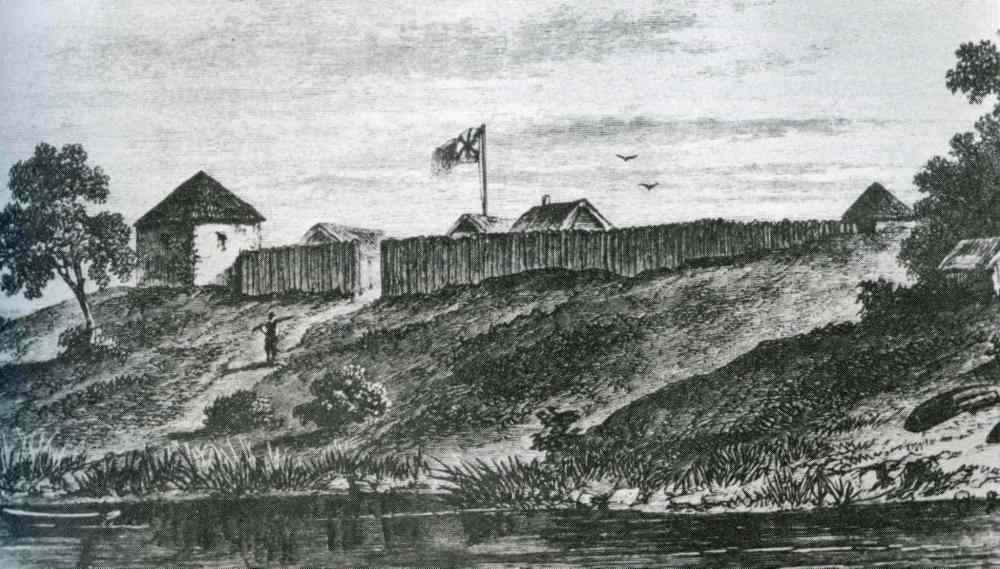

To review what any school kid knows, or should know, the document was signed July 18, 1817, at the site of Hudson Bay Co.’s Fort Douglas on the west bank of the Red River, just north of the present-day Alexander Docks.

Indigenous leaders agreed to grant Selkirk’s settlers farmland lots “to have and to hold forever,” stretching two miles back from the banks of both the Red and the Assiniboine rivers.

All together, the grant amounted to 24 square miles and helped give birth to the postage-stamp-shaped province 52 years later.

In return, Selkirk promised to send annual presents (also described as quit-rents) of 100 pounds of tobacco each to be delivered to the Saulteaux at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine and the Cree at Portage la Prairie.

He never paid, dying young just three years after the treaty was inked.

His estate handled the treaty until the mid-1800s before handing control back to the Hudson’s Bay Co. In 1870, the colony formed the basis of Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

“I’m taking a serious look at the Selkirk Treaty,” said Manitoba treaty commissioner Loretta Ross. “I’ve come to understand it was the precursor before the numbered treaties. It set the stage for the numbered treaties and it has an important place in history.”

In a wider context, the Selkirk Treaty is a forgotten keystone to a side of Manitoba history people don’t often think about, Ross said.

“I don’t think the Selkirk Treaty has been given the place it deserves, in the context of the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. On both sides, they had to find a way to co-exist and they did that in the Selkirk Treaty. That spirit and intent was there. It bears further study and it’s so interesting to understand the significance it plays in the history of relations between First Nation and the Crown, as well as with the province of Manitoba, for our local history,” she said.

“The important thing now is to get people to think about this and start asking questions.”

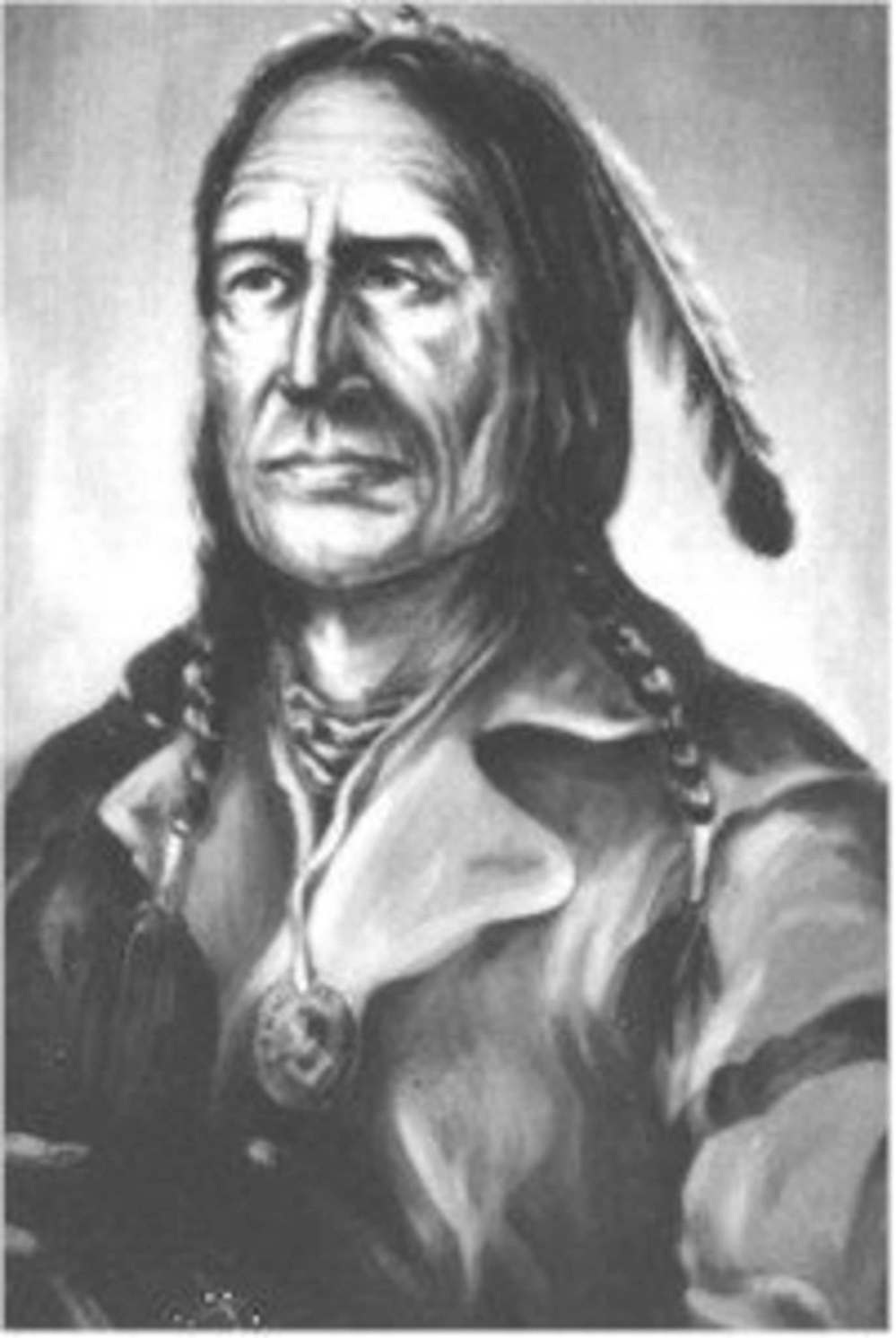

History is kind to Chief Peguis. He’s remembered as a loyal friend — “the best friend a settler could ever have,” Selkirk Settlers recalled in their own accounts of early days on the Red.

And there’s probably no more poignant moment of his leadership than what happened a year before the treaty was signed.

In 1816, a brash, arrogant military man and the HBC governor at Fort Douglas thought he could bluster down an armed charge by Highland Cree trader Cuthbert Grant Jr.

Gov. Robert Semple was dead wrong and the result was the Battle of Seven Oaks.

It was Peguis and his people who helped the survivors flee and then buried the dead. The image that stick out in those accounts is personal: Peguis holding a then-dead Semple in his arms and weeping.

After decades of silence, many, including both Indigenous and non-Indigenous descendants, say the treaty’s legacy is stronger than ever, offering signposts for the journey of reconciliation Canada now faces.

A couple of years ago, Cree Bill Shead and Brokenhead Ojibway Nation Chief Jim Bear got together and started a conversation about whether to mark the treaty’s 200th anniversary. Both trace their roots back to St. Peter’s, the home of Chief Peguis and community that took its roots from the treaty.

“That was the beginning of it… It took off from there,” recalled Bear, a direct descendant of Peguis.

Shead, a retired career military man, former mayor of Selkirk and a Peguis First Nation band member, is one of a handful of people at ease bridging the Indigenous-non-Indigenous silos in Manitoba.

Shead is co-chairman of a committee poised to throw a huge party recognizing the 200th anniversary of the Selkirk Treaty signing, with events in Winnipeg, Brokenhead, Selkirk and Peguis. The current Lord Selkirk arrives Saturday and he’ll be on hand for re-enactments, social events and celebrations of the ties between the Scots and the Ojibway.

“The Selkirk Treaty is the first treaty in Western Canada and it was signed before there even was a Canada. It marked the beginning of the relationship between First Nations and the Crown and cemented a friendship between Chief Peguis and Lord Selkirk. It shaped not only Winnipeg and Manitoba but the nation itself,” the committee said in a statement in June.

John Perrin, former St. Andrew’s Society president, is the other committee co-chairman.

Perrin is from a distinguished family that traces its roots back to Col. Garnet Wolseley, who led the Wolseley expedition, the force prime minister John A. Macdonald authorized to put down the Red River Rebellion in 1870.

“You could take in the big picture and think of Peguis himself as an architect of Canada. He was the architect of peace and order on the Red River. He always did honour the treaty and St. Peter’s (reserve) was very successful.

“This treaty created a positive outcome at the time and led to peaceful settlement. And it might be something people now want to take into consideration when it comes to reconciliation and how Canada should honour these treaties,” Perrin said.

Glenn Hudson, current Peguis First Nation chief, said the fact the treaty was never honoured means there’s an opportunity to renegotiate it.

“That’s something we need to bring light to, and educate people on, that being, it was the one of the very first treaties in Western Canada,” Hudson said.

A re-enactment planned at Peguis next week will focus on a headdress chief Eddie Thompson gave to George Douglas-Hamilton, the 10th Earl of Selkirk, in 1967. The current Lord Selkirk, James Douglas-Hamilton, initiated the return. It is currently held at the Manitoba Museum.

Two years ago, Maureen Matthews, the museum’s curator of cultural anthropology, flew to Scotland to retrieved the floor-length headdress and powwow regalia that Selkirk and his wife received during the couple’s visit to the First Nation 50 years ago.

“The interesting thing about the Selkirk Treaty is that it reflects the Indigenous interpretation of treaties, that they are ongoing, that they mark the start of an ongoing relationship,” Matthews said. “And this one reflects an ongoing relationship between Peguis First Nation and Lord Selkirk.

“The treaty wasn’t about giving up land. It was about sharing land. And, interestingly, it was like a reserve for the settlers and they were policed by Peguis’ people.”

The group behind the bicentennial events is diverse, but behind all the diversity, there’s a single current running through the effort. Just about everyone involved has a personal family tie back to the early settlement, either Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

“That bond has continued for sure,” noted Bear, who has a personal connection with the current Lord Selkirk. “These connections just keep happening.”

It could be those kinship ties between clan-based societies, as the Scots and the Ojibway were at the time, turn out to be the greatest legacy of the treaty.

The signatories and their symbols

Two hundred years ago, on July 18, 1817, the Selkirk Treaty was signed at Fort Douglas. The exact location, just off Waterfront Drive and north of the Alexander Docks, is marked with a monument in honour of the Selkirk Settlers.

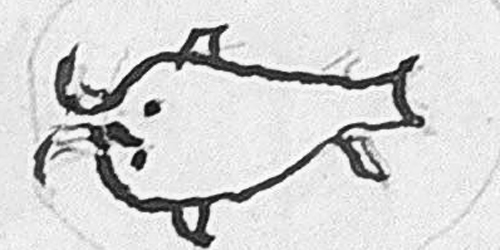

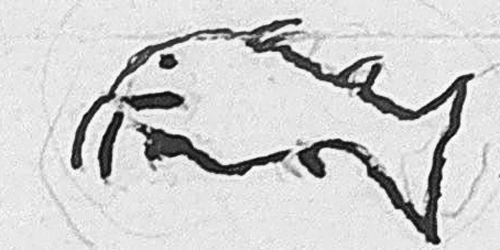

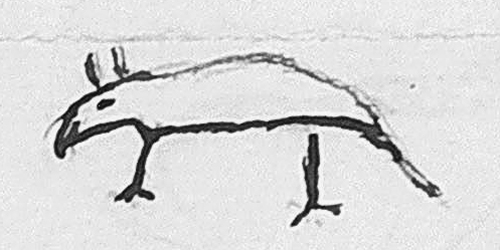

The map that’s part of the Selkirk Treaty is signed by five chiefs, each with an animal symbol. For 200 years, those symbols have puzzled people: were they personal symbols or clan symbols?

The current thinking is they were symbols to indicate each chief’s relationship to a particular territory and they also indicate a wider meaning, related to Indigenous cultural practices and beliefs that stretch back thousands of years.

Based on interviews and research by people such as Seven Oaks House Museum curator Eric Napier Strong and material from books, including Donna Sutherland’s Peguis, a Noble Friend, the Free Press fills in a few blanks on these mysterious elements.

Le Sonnant

Mache Whesab (Many Sitting Eagles) is the only Cree chief to sign the treaty. He had occupied the region longer than the other signatories. He was then in the Portage la Prairie area.

His people later migrated west and settled in Saskatchewan’s Qu’appelle Valley. His son signed Treaty 4.

He drew a symbol of a lizard or a salamander to represent his territory.

La Robe Noire

Mechkadewikonaie was an Ojibway chief, also from Portage, in the area of the White Mud River and Rat River at Totogan, south of Lake Manitoba, and to people now living in Long Plain, Swan Lake and Sandy Bay.

Some accounts link him to people in Dakota Tipi, as well. It is also reported he had a famous descendant, Yellow Quill, who signed Treaty 1. He drew the symbol of a fish to represent his lands between The Forks and Musk Rat Root River west of current Portage la Prairie.

L’Homme Noir

Kagiwoksbmoa is recorded by at least one fur trader of the time as being from Lake of the Woods. Written records don’t note anything about him or his people after 1817.

He also signed with the symbol of a fish and shared land in the treaty on the Red River south of Pembina to Red Lake (Minnesota).

Le Premier

Oukidoat, an Ojibway chief, was noted to be one of the most powerful leaders in the Red River area, before Peguis eclipsed him in stature with the growth of the settlement. Fur-trade records place him in the Rainy Lake area in 1804.

In 1814, he gave a speech at The Forks, condemning the “presumptuous attitude” and actions of the Selkirk Settlers, which the North West Co. widely circulated as part of its campaign to get rid of the settlement.

His lands were along the Red River south to Pembina. His symbol was the bear.

Peguis

Peguis was the Ojibway chief who befriended the settlers and lived the rest of his life along the Red River, a peacemaker and diplomat dedicated to the relationships he believed were at the heart of the treaty.

He was also known as “Cut Nose” after the tip of his nose was bitten off in a fight when he was a young man. He took the name William King, and gave the last name Prince to his children, in recognition of the treaty.

Most accounts say he took the name decades later, when he converted to Christianity, but at least one oral tradition links the name to the day the treaty was signed.

In any case, Peguis took the name King in recognition of the treaty and his belief it placed him as the equal to Selkirk’s sovereign, the British king. The name Prince indicated his children were expected to build on his work for peaceful, co-operative relations on the Red.

Some interpret his symbol as a wolf. Others say it was a marten.

Broken promises, lasting bonds

Canada turned pre-Confederation co-operation with Indigenous people into cruelty and contempt, but many descendants of the Selkirk Settlers know how Peguis and his followers helped the newcomers

Every year, the people of Peguis come back to the old stone church near Selkirk on Father’s Day.

The St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church is the only thing left of the once-vibrant St. Peter’s reserve, home of Chief Peguis and his community that took its roots from the Selkirk Treaty. It was a two-mile parish lot, just like the rest of the Red River settlement lots.

St. Peter’s was an Anglican parish and known as the most Christian Indigenous settlement in Canada. Homeowners had property rights. Farmers sold surplus crops at the settlers’ markets, camping overnight along Peguis’s favourite pathway off the Red, through what is now known as Kildonan Park.

By the 1850s, St. Peter’s boasted the only harness maker and tinsmith in the entire Red River Colony.

“Unlike other settlements, which were established behind a frontier or along a coast, Selkirk’s colony was isolated from other settlements by thousands of miles and did not have a ready escape route to the sea. The settlers had to depend on developing goodwill and co-operation with First Nations which surrounded them in great numbers,” Indigenous author and historian Rarihokwats wrote in his online History of the Ojibway Nation in Manitoba.

In 1907, that rich farmland was swindled from the Peguis people.

They were sent north to swampland in the Interlake where Peguis First Nation still battles yearly spring floods. In recent years, Peguis negotiated a $126-million compensation settlement with Ottawa over the illegal land surrender.

The forced removal of the people is a sorry chapter in a First Nation-settler arrangement considered unique in the history of European settlement in North America.

Not everyone went north. The people of Peguis scattered; some stayed in Selkirk, such as Olive Lillie and Bill Shead and their families. Descendants of St. Peter’s now live in Brokenhead, Sagkeeng, Long Plain and Sandy Bay First Nations, and even Saskatchewan.

It is principally the descendants in Selkirk, Brokenhead and Peguis who pay homage to their ancestors at the old stone church. Their family plots are well-maintained by Lillie’s descendants. Her family bought a farm across the river the same year as the removal and they’ve been there ever since.

Shead grew up a couple of kilometres away from the old St. Peter’s reserve. “My grandmother is buried here. Her grandparents lived at St. Peter’s,” he said.

On a walk through the graveyard, he pointed out his family plot and others, such as the woman whose nephew was a key shipbuilder in Belfast. He help build the Titanic, the grand ship that wasn’t supposed to sink.

“Sketches exist that show this place. There was the church, there were schools, homes, roads. They weren’t living in teepees or lean-tos. What they had was substantial. That’s what we had 50 years before Confederation,” Shead said.

Even after Confederation, when an influx of newcomers and Canadian ways marginalized St. Peter’s, a lot of old connections held.

“The Selkirk Treaty was basically ignored by the government of Canada, and what they did with the numbered treaties was to start from scratch. There are two things I think are important here: there’s Peguis and then there’s the people of Peguis. They continued to be loyal to their friends and that included non-Indigenous people and they got involved in everything that was helpful to their friends,” Shead said.

A military man retired after a long career in Canada’s navy, Shead takes a special interest in the veterans of St. Peter’s and Peguis. “There’s a history right here in the ground that shows the loyalty of the people of Peguis to their friends, the descendants of the Selkirk settlers,” he said.

Like the rivermen recruited from St. Peter’s to ply the waters of the Nile River for the Wolseley expedition in Egypt in the 1880s. A British empire war forgotten by many, but not by Peguis people.

“I mean, who else would go up the Nile except for personal friendship? It’s not the Crown, it’s not the flag and it’s not the country. You don’t go out to save someone’s life because of that. You go out because he’s your buddy and that’s the history of wartime service,” Shead said.

St. Peter’s graves and the stories of the men and women in them reflect the loyalty to friends that goes back to 1817, Shead said.

The Settlers

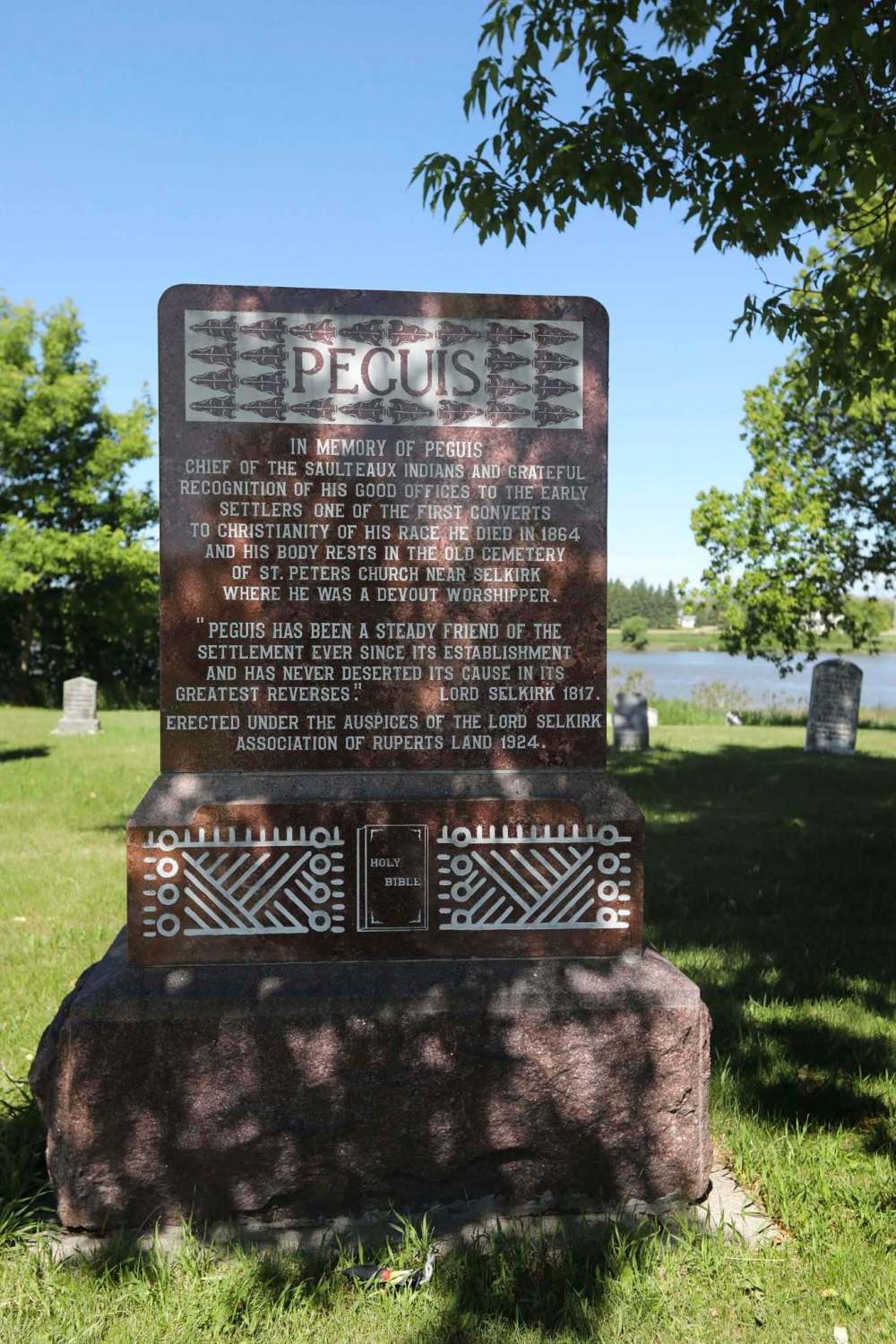

Descendants of settlers marked the first 100 years of the Selkirk Treaty with two monuments to Chief Peguis.

One is a statue at Winnipeg’s Kildonan Park, erected in 1923 on the site of a former settlement farm, near Frog Plain. The location was chosen in memory of Peguis’s well-travelled path. His frequent visits up and down the colony over the decades almost always included a short cut through the old McKay farm.

The second monument was erected in 1924 near Selkirk at St. Peter’s Dynevor Anglican Church. It’s pretty much all that’s left of the original St. Peter’s reserve where Peguis and his people lived in the early decades of Red River settlement.

In many ways, erecting the statues were moves of defiance for the Scots, coming a few years after the illegal surrender of the original St. Peter’s reserve. Everyone was forced off, the current Peguis First Nation was created and the removal is known now as Canada’s Trail of Tears.

“They may have talked about putting up a statue to Lord Selkirk, but when it got down to it, they put the monuments up to Chief Peguis,” said Gordon Cameron, a descendant of Selkirk Settler Donald Gunn.

In 1912, the second and third generations of the original settlers formed the Lord Selkirk Association of Rupert’s Land. To this day, membership is restricted to descendants of settlers from 1812 to 1836.

“I had the impression there’s a closer tie to Peguis than to the treaty. The connection was personal. We always learned, it was our personal history. We were always taught how Peguis had helped… it’s well known that Chief Peguis and his people helped the settlers,” Cameron said.

Many descendants of Selkirk’s settlers, such as Cameron, describe the forced removal of Peguis people as a direct “betrayal” of their own history.

People forget for a small group of Manitobans, connections with Peguis and the Métis remain strong, bonded by blood in ties of intermarriage that cross Scottish, francophone, Métis, Ojibwa and Cree in Manitoba.

“It’s interesting when you think of the Selkirk Treaty. The settlers were essentially on a reserve, and it was defined, two miles in up and down the river. The rest was outside, for the First Nations,” Cameron said. “I always get a smile when I say that.

“But when you think about it, when you go back to, say, the 1820s, Peguis could go anywhere. If he wanted to bring food back to help people, he could. There was a different relationship between the two peoples. And I guess it’s one of power. Once Canada took over, it changed. They held the power of the land and we know what followed,” he said.

An image is burned in his memory, based on bittersweet recollections of the monument’s unveiling at the old stone church.

“You know what something looks like if it’s only been abandoned for about five years. The church was still there. But when they put that monument up, you would have still seen the foundations of St. Peter’s, the collapsing homes of the old settlement,” Cameron said.

“The association wanted to mark the place, and the place they indelibly marked was St. Peter’s… and Kildonan.

“It’s interesting, the value of carving things in stone. Hundreds of people go to the park, they pass the statue, see the quote. And that’s important. Peguis was the leader of that group and he was a friend,” Cameron said.

The Métis

It’s strange to think Métis leader Louis Riel might never have been born or become a father of Manitoba if it hadn’t been for Chief Peguis, Lord Selkirk and their connections to the Lagimodiere family.

Jean Baptiste Lagimodiere and Marie Anne Gaboury were Louis Riel’s grandparents, their Selkirk settlement farm his birthplace, their long experience in the Red River Colony his first memories.

So it’s odd but fitting a clerical error on the copy of Riel’s death certificate after he was hanged in Regina as a traitor to Canada names him as Louis Lagimodiere, says Alan Lagimodiere, a direct descendant of Lagimodiere and Gaboury.

“After Riel was hung and they sent his body body to Winnipeg, the death certificate actually had ‘Lagimodiere’ on it. And that is crossed off and ‘Riel’ written in behind it.”

Lagimodiere, a veterinarian and Conservative MLA for the riding of Selkirk, is intensely keen on his family’s history with early Manitoba. He believes there’s probably good reason for the mistake.

The Lagimodiere family name stood out, because of their links to the Métis and the Selkirk settlement.

Jean Baptiste’s wife, Gaboury, was the first woman of European descent to settle in what is now Western Canada; for that she is widely known as “the Grandmother of the Red River.”

History records her as the mother of the first legitimate non-Indigenous baby born in the region.

Jean Baptiste played a key role stabilizing the colony with an act of sheer bravery; he got past a North West Company blockade intended to cut the fledgling colony off from the outside world and slipped critical communications from Fort Douglas directly into the hands of Lord Selkirk, then in Montreal.

It was astounding feat, given he had only a musket and a rabbit snare with him when he set out on the 2,900-kilometre trek.

“Walking, mainly walking,” Alan Lagimodiere emphasized.

Selkirk repaid the couple with land, making them one of the original Selkirk Settlers. Their farm, now a park, became the first francophone settlement in Western Canada.

Chief Peguis took in Gaboury and their children the winter of 1817 while Jean Baptiste was away.

“Nobody seems to remember that part of the history,” Lagimodiere said.

“Our family, I was told, remembered my grandmother for being a very learned person with a close association to Chief Peguis at the time. I would think she understood fairly well the intent of the treaty. And we were told the intent of the treaty was to have peaceful relations with the new settlers and to share the land with them.”

Looking back, Lagimodiere wonders if Peguis’s long talks with Gaboury percolated into Riel’s actions 50 years later, when he tried to set up a provisional government based on principles of equality and Indigenous values and ended up fighting the Red River Rebellion.

“No document more important”

Q&A with Niigaan Sinclair on the Selkirk Treaty

Indigenous nations held the balance of power on the Red River in the early 1800s and the Selkirk Treaty reflects that reality, making it different from the treaties Canada settled starting in 1871, with Treaty 1. It wasn’t about a land purchase. It was about creating new relationships of peace, order and mutual co-operation.

Niigaan Sinclair, an associate professor in the University of Manitoba’s native studies department, considers the Selkirk Treaty the most important document in Manitoba history for those reasons.

Free Press: Why is the Selkirk Treaty significant?

Sinclair: It sets the groundwork for non-Indigenous relationships throughout the Prairies. There is no document more important. And it’s also the most ignored because it’s the document that bucks the trend of the last 150 years of genocide.

FP: So let’s go back 200 years. What was Chief Peguis thinking when he agreed, along with the four other chiefs, to grant rights settlement to Lord Selkirk’s people?

Sinclair: Peguis makes an agreement with Lord Selkirk to share land on the Red River. Now, some people have interpreted that as the sale of land along the river, but I’ve never heard that. Peguis worked very hard to try to teach Selkirk there was law along the Red River and the law was: when you come into this territory, you are joining something. You’re not dominating it. There’s already an entire system of relationship-making and international trade the Red River embodied.

FP: The early 1800s were turbulent times and Peguis, himself, had only recently moved in, right?

Sinclair: You’ve got to think that the world of the 18th century is a different world than it is now. Simply put, Indigenous people held the balance of power in that world.

For years, Peguis had been settling lands up in Netley Creek, but he and other people from the Sault (Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.) had been using that land for hundreds of years and that’s well-documented.

The Anishinaabe were well-known along the Red. We didn’t have the extensive network the Cree did, but we certainly had relationships.

The Red River was one of the boundary lands between us, the Assiniboine and the Dakota and Nakota.

FP: I’ve heard you talk about something called the “white wall,” that the settlers were a kind of cushion between the Anishinaabe and the Dakota over the buffalo. What’s that about?

Sinclair: Peguis’s got this struggle… the buffalo are travelling at the same time and there’s a kind of ongoing conflict with the Assiniboine. What Peguis was saying is, you can have access to this territory and we will share it with you.

That didn’t mean they would have it all. It also involved… a strategy of Peguis and the other chiefs to put up a wall of white people in the path of the buffalo migration, a way of stopping the Assiniboine from having access to the buffalo, and… (to) give the Ojibwa a monopoly on the buffalo in that region.

Peguis took over lands left after a smallpox epidemic decimated Cree and Assiniboine on Netley Creek. Accounts he later gave to settlers like Donald Gunn indicate those survivors welcomed him and his band. They actually told him they were sick of trodding on the bones of their dead and he was welcome to it.

There’s sickness happening throughout Indian country in these days as food lines are disrupted, but Indigenous people still hold the balance of power.

This all begins to shift after the War of 1812. There’s tremendous stress on immigration into the West, an influx of settlement, Selkirk and the rest.

As people are coming into Manitoba, Peguis sees the writing on the wall. He saw a world that was dawning, and he saw how bad it could get in Upper and Lower Canada and he didn’t want that to happen in Manitoba.

He wanted people to have an understanding how to create healthy and sustainable relationships. The hope was the Red River Settlement would be this bastion of international trade, that people would constantly recreate relationships of peace, kindness and family along the Red River.

FP: Under the treaty, Selkirk was supposed to pay gifts of tobacco every year. He didn’t, did he?

Sinclair: Selkirk took off and died after that and he never returned. For Peguis, that was an egregious pain, a violation of the treaty. In fact, he wrote letters all the way to the king, saying the “Silver Chief” (the name Peguis gave Selkirk as part of the treaty process), he said he would come back.

The letter, in 1859, to the king, his son wrote it and he said: the Silver Chief never returned and we no longer recognize this treaty. Why are your people still here? You need to send your representative and remake this treaty with us.

alexandra.paul@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Saturday, July 15, 2017 4:18 PM CDT: Typo fixed.