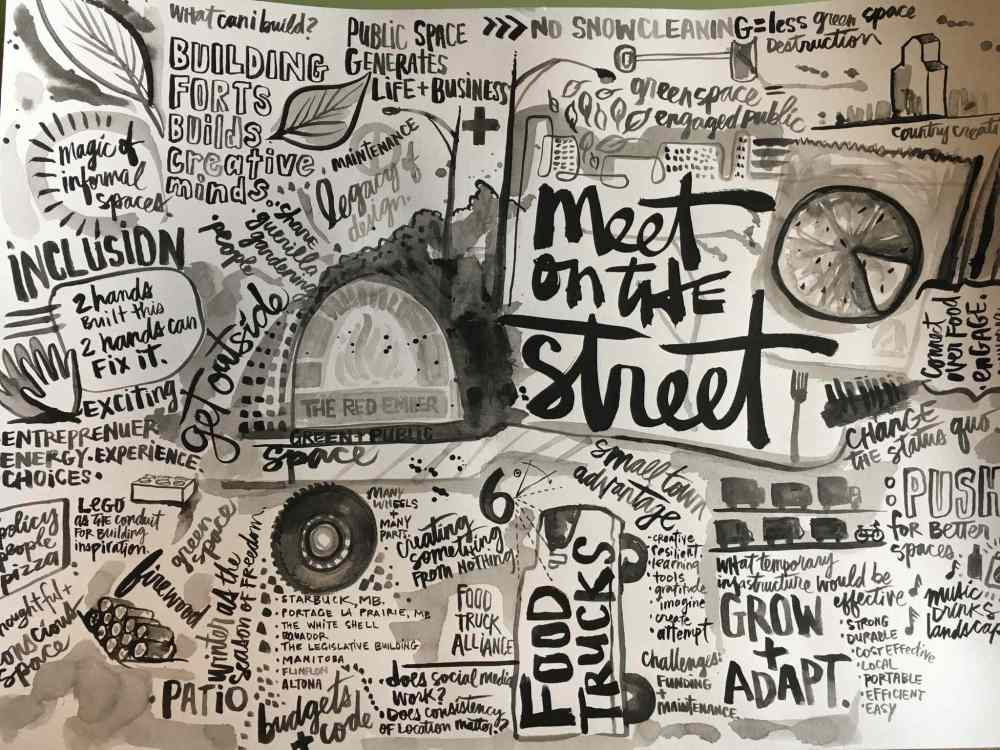

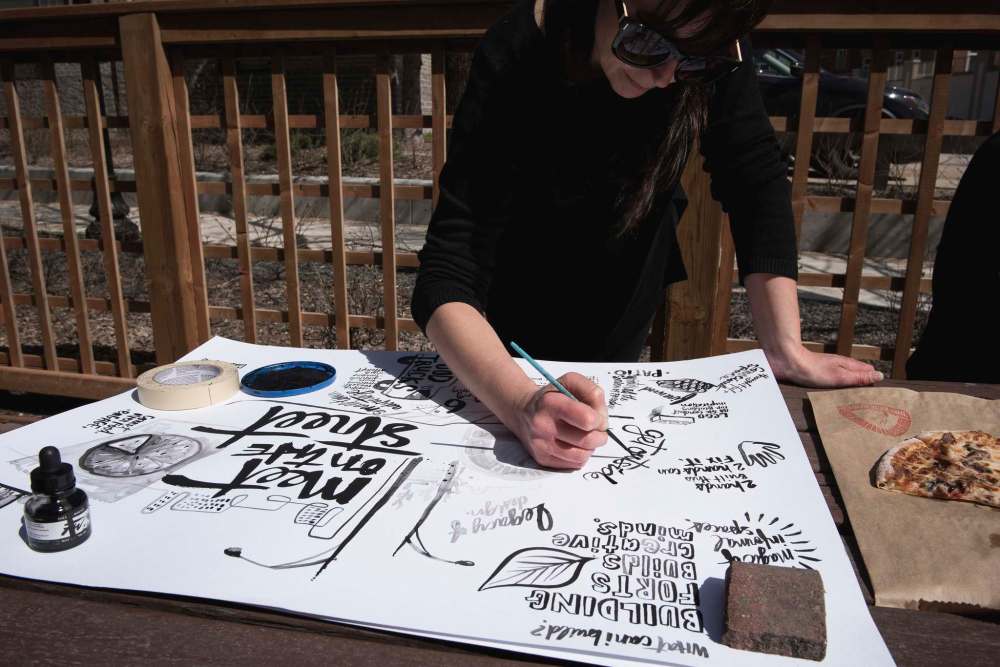

A slice of urban life

Red Ember food truck creates conversation around public space activity

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2017 (3101 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In The Social Life of Small and Urban Spaces, William H. Whyte provides an intuitive critique of urban spaces and proposes ideas for how these places can be improved upon. As Whyte suggests, some of the city’s most active public spaces can be easily traced with your nose. In Winnipeg, your nose will likely lure you to Broadway, where some of the city’s finest chefs have become mobile with food trucks, adding new activity along this historic street.

When HTFC Planning & Design’s Robyn Gibson and Lana Reimer sat down with Steffen Zinn, Konrad Zinn and Thomas Zinn, an appetite for a change in public policy around street corner eateries was sparked.

The group also talked about how the built form could better respond to the temporary nature of food trucks — considering design features such as portability, durability, cost-effectiveness and ease of movement — from bistro tables and chairs that can be easily stored and moved around by patrons to parklet-style patios for food truck operators to use and transport from one festival to the next.

Steffen, Thomas, and Konrad come from a family genealogy of landscape enthusiasts. Their rural upbringing has seemingly influenced their desire to build things: “There were lots of long days out at the farm playing with Lego,” Steffen says. “We used to strip telephone wires and make battery-powered streetlights. We were amateur engineers.”

Steffen, owner of Red Ember, took this love for Lego to elevated heights, seeing an opportunity to invest in his first food truck. “I built something from nothing. I designed and built the Red Ember and the entire fleet. I also built a cargo tricycle to use at Folk Fest, to make life a little easier when transporting ingredients to and from the campsite.”

When he isn’t cooking pizzas in a wood-fired oven, he’s still building: “When you’re an entrepreneur, you are always thinking about what’s next and what more you can do.” Previous to his foray into food trucks, he trained and worked as a professional chef for 21 years, working at Manitoba destinations such as the Pine Ridge Golf Club and St. Charles Country Club.

Thomas was born in Winnipeg but raised in Springstein, Man. After attending Red River College for its landscaping apprenticeship program, Thomas followed his father into the family business, Meridian Landscaping and Nursery.

Cousin to Thomas and Steffen, Konrad grew up in Lauterbach, Germany, and later moved to New Brunswick where his father Johannes found work as a master agronomist. A desire to reunite with Manitoba family would bring Konrad to Springstein. Konrad has been a landscape journeyman for more than eight years, having taken over the family business, J&K Zinn Landscape Contractors.

Because of their mobility, food trucks provide business owners an opportunity to incubate and test their products with a variety of people. On Broadway, food trucks have almost become the exclusive caterers to outdoor life in the summer.

The businesses on Broadway, as Gibson and Reimer argue, are less nimble than food trucks and need to evolve: “Businesses on Broadway could capitalize on the excitement that food trucks bring by creating patios in front of their restaurants — giving people another reason to linger longer,” Lana says.

They cite street interventions such as plantings, patios, and outdoor spaces as design opportunities and examples like Forth for businesses on Broadway to emulate.

Forth (a bar/coffee shop/café on McDermot Avenue) recently placed a patio in front of the business in such a way that invites both public and private participation — providing seating for those enjoying a cup of coffee from their establishment, and those who aren’t.

As explained by Gibson and Reimer, owners of businesses like Forth have seen the value of generating pedestrian life as a way to generate business.

Gibson, a landscape architect of six years, was born in Flin Flon. With a RCMP officer for a father, Gibson found herself living in places like Creighton and Vancouver, but calls Winnipeg home. Her design practice is inspired by the engagement that takes place in leftover, informal spaces and by “those little magic things that happen just based on the people that happen to be there at that point in time.”

A practicing landscape architect of four years, Reimer grew up in Portage la Prairie. Her biggest landscape inspiration is her two-year-old daughter: “Everything I do now revolves around my daughter, but it’s a good thing — we get to take in new landscapes together.”

Food trucks take over controlled spaces, and offer an interruption to public life on streets in a temporary way. They bring people outdoors. How do food trucks activate our urban experience?

Steffen: We see people coming out of their offices and buildings to interact with one another. At least two or three times a week, you see families spread out a picnic blanket, with their kids toddling around. They’re all enjoying pizzas and drinks and then they go on their way.

Perhaps food trucks are a way for working professionals to see their kids — the same way that I would see my dad during the day when he would be working on the farm. It adds a bit of an experience.

The food trucks bring life and encourage the younger generation to come downtown. They get to be outside.

This year, there wasn’t enough space in the public realm to eat, so we bought stand-up tables. We figured people wanted to stand and have their lunch because they were stuck sitting down for most of the day.

We only brought with us five tables, so people had to share this eating space. It encourages people to strike up a conversation and make new friends.

Gibson: It’s European-style; the long table.

Reimer: It offers that space for that connection to happen.

Gibson: I hadn’t thought about food trucks as a way to bring kids into the downtown. I think that’s an interesting notion.

In the city, you don’t have many opportunities to have lunch with your kids during the day, unless you are a stay-at-home mom or dad. You have to figure out child care. You think, “Maybe we don’t have enough time if we have to sit in a restaurant, or the kids or too young for that, and it’s just too much hassle.”

You start thinking in a compartmentalized way: this is work time, this is when you go home, and this is home time. Not only are your children’s lives overly programmed, adults lives are overly programmed.

Food trucks are in a public space — it’s not so controlled. In a way, they provide an opportunity for the partner and kids to meet at noon for lunch — it’s not incredibly expensive, there are a lot of options, you can sit outside, and the kids can run around. It shakes up the whole notion of where and when these things are supposed to happen.

Barteski: We have a lot of kids, so we’re like, “Yay food trucks! You go there, you go there, there, there and there!” There are multiple options.

Thomas: And everyone is satisfied.

Konrad: Food trucks need to be where the people are, where the lunchtime rush is. The challenge with that is the existing infrastructure — where people can sit.

Red Ember is always parked across from the Legislative building, which I think is a good place to be located. There’s lots of green space nearby.

In the future, planners and designers should consider how food trucks add to people’s experiences in the city, and how public spaces should be shaped in such a way that supports this emerging activity.

Every renovation project in the downtown often cuts budget to landscape. Because of this, clients proceed with the bare minimum. Sometimes, they’ll want to maximize parking.

How do we combat this? It’s about getting owners to understand the value of green space, for them to support the interactions of people in front of their properties. When others see how these businesses are in favour of cultural experiences, the businesses are seen in a positive light as a contributor to civic life.

Reimer: And I think that’s part of our job as designers, as landscape architects, as planners, to communicate that to the client or the owners, that these things are very valuable. It’s not just about how many people you can cram in said retail space or a parking spot. It’s about offering public spaces for people. We need to push for that because it’s very important. It creates a ripple effect.

Gibson: Going back to the theme of innovation. Whatever we design should take into consideration our very different and distinct seasons. You need to make sure that whatever you are doing has multiple functions.

Maybe it’s a hard-scape plaza that can morph itself into a bunch of different things that would be helpful for food truck activity. Perhaps the space needs to allow for kids and families on blankets during the day, but perhaps maybe beer drinking in the evening.

This is how we try to design most things. But all of this needs buy-in from the property owner and advocacy from food truck operators. How can we encourage local businesses to pick up on the activity being generated with food trucks?

On Broadway, for example, a lot of the restaurants don’t have patios or outdoor spaces. The food trucks have the potential to be generative and to create an active node on Broadway, yet the businesses aren’t capitalizing on this activity.

Reimer: It goes back to being innovative and using the most of the little spaces that we have downtown.

On Elgin Avenue, for example, local makers transform the alleyway when they sell their wares in the summer. On John Hirsch Way, our firm has added planters for the community to guerrilla garden.

These food trucks are guerrilla in that sense, in that they are trying to reclaim spaces and make them for people. I enjoy walking through the sidewalks as people are eating food truck food. I like feeling part of it. It’s like sharing a table.

It reminds you that streets and sidewalks are meant to be shared. It sets the stage for people interaction to happen. And that’s why I like landscape architecture because it truly is about people.

Syvixay: It’s about pushing new priorities and public policy. Food trucks interrupt Broadway in such a way that forces new conversations, new perspectives, and to challenge status quo.

Today, the conversation is centred on where people can park, but maybe tomorrow, the conversation will focus on how we can make Broadway a place for people, not for cars.

In Winnipeg, food trucks present interesting opportunities and perhaps some challenges. In terms of opportunities, they help to animate the street, bring pedestrians out into the public realm. But there are some tensions — restaurants and businesses often assert food trucks are taking away from their business. What are your thoughts on this? How do you find the balance?

Steffen: The city was very inclusive when deciding where the food trucks should go and policy around that. In my role as the president of the Food Trucks Alliance, I met with the Winnipeg Parking Authority often. They wanted to forge a policy solution that would make everyone happy.

One of the things that we worked out was to limit food trucks to two per block face, to ensure there was more room for parking. This would spread food trucks out along Broadway a bit more. In the past, there used to be about five food trucks parked on one block face.

Some operators say they have lost business because of this policy and how the “food court feel” has been lost. But then, others say they are doing well and they are pleased with their area.

I guess I have a different mentality. My background as a chef at a private club, we always treated our customers as members. As such, we try to be very consistent with our spot on Broadway. We don’t jump from one place to the other because we don’t want to disappoint our customers who look forward to seeing us.

We encourage the city to strengthen fines against food trucks that aren’t abiding by the rules, that are depositing their waste in street garbage cans, and that aren’t being careful about the grey water they produce. Sometimes, you see grey water dribbling out of older food trucks. It doesn’t look nice and it takes away from the atmosphere.

We want to be part of the conversation instead of the city ramming something down our throat. It’s good to start talking to departments earlier, like public works or waste and water.

We want to be good corporate neighbours to the people and businesses on Broadway.

Syvixay: It’s interesting how food truck operators are being so proactive, wanting to drive this discussion about how to best co-habitat urban spaces so everyone can benefit. But again, the discussion is still rooted in maintaining status quo, about trying to control.

So I wonder, on the design side, how does regulation take away from the spontaneity, the interruption, and the temporary that gets people so excited? I’m not too sure what the answer is, as I understand the role of regulation in creating predictability. But there’s something very exciting about food trucks just popping up.

Gibson: I think that’s a very difficult line to walk. I guess what may be a novelty of food trucks is that they are mobile, they can go anywhere and operators can just show up and start selling stuff. You get this serendipitous pop-up and interruption of the routine. You could decide to pop up somewhere and what if nobody shows?

Barteski: That’s part of learning, though, right? Food truck owners, or small business owners, are highly motivated to make adjustments quickly and effectively. So if you show up and nobody is there, then guess what? You’re not going there next time.

Gibson: But public policy doesn’t lend itself to those quick-moving, spontaneous shifts and decisions of where you should go, and what you want to do.

I’m going to go on a social media rant now. It’s my pet peeve. It’s a thing, “Oh, there’s a pop-up, didn’t you know? It was on social media! Are you a member? Are you on Facebook?”

It’s spontaneous only for those who have access to that social media account, that Facebook page.

Barteski: That’s what I think makes it exciting and exclusive.

Gibson: But is public space supposed to be exclusive? Is it supposed to be something generative for all people no matter if you have enough money to buy a pizza or the hot dog, or if you have Internet access or can afford a phone?

Barteski: Social media creates a buzz or excitement. People really feed into that.

Reimer: My mom’s on Instagram but she doesn’t necessarily follow food truck accounts.

But she’s downtown and during her walks at lunch, she’ll run into a food truck or see lots of people gathering in one area. And that’s how she learns about it. And that’s inclusive.

Gibson: It’s inclusive but if you don’t happen to be walking by, and you aren’t doing those things, then you’re not part of it.

Barteski: The magic behind the moveable trucks is that you find them some days; you don’t find them on others. If you really want to know where Red Ember is, look it up, they’ll tell you.

Steffen: In that aspect, we’re a bit boring. We are about location consistency. I like planning things out. It might be my German background, or my serving background.

I’ve seen other food trucks decide to randomly pop up in all sorts of locations but they fail miserably because nobody can find them. They may make tasty food but location is everything.

Steffen, why are you opening up a brick-and-mortar restaurant at The Forks? How does it differ from your food truck business model?

Steffen: We come from a large family of entrepreneurs. I always knew I was going to own my own business. In the hospitality industry, there are a lot of up-front capital costs.

I figured food trucks were an easier way to get into the game and to build a clientele base, at the same time, generating income to put towards a bricks-and-mortar restaurant, which was always the ultimate goal.

And so that’s a big reason why I went the food truck route, as well as it gave me an opportunity to build something with my own two hands. For many, food trucks are an incubator of sorts, a way to test out your product with people, to see what they like.

The new restaurant is the continuation of our business story, I suppose. And what’s important to me is to give opportunity to my staff to be business owners.

Red Ember Common at The Forks is a partnership between me and Quin Ferguson, who was the truck boss at Red Ember. He’s going to run the restaurant at The Forks, and that’ll be his baby. For him to be able to make a wage, but also to make an income with dividends, he is able to move forward his life in the direction that he wants to.

We’re already talking about the next place that’ll be opened in three to five years. This gives staff to gain management experience, and I say to my staff, “If you put effort in, and show desire to do it, and I’ll partner on something with you. We’ll use the name to boost, to build something new.”

Syvixay: Your comments bring us full circle to the conversation around rural upbringing. I think the values of community, sense of ownership, and family, are things that the Zinns value — about building a bigger pie. Maybe that’s the symbol of food trucks. It’s about building a bigger pie for businesses on Broadway.

Reimer: I think they need to embrace and to capitalize on this energy. Again, it comes down to policy, as well as food truck owners engaging business owners to get them excited about what’s coming, what’s emerging on Broadway.

Steffen: I think another hurdle will be ensuring features like parklets are made a priority. The city wants to tax these even more, trying to limit these small patios that are being advocated for by small business operators.

Syvixay: We shouldn’t be taxing business owners who want to innovate and implement good things for the city. Additional fees and other barriers make it difficult for people to contribute to a healthy city.

Gibson: This is where existing green spaces are important. Jason (Syvixay), you talked about how Memorial Boulevard was shut down to allow for food trucks.

Syvixay: Yeah, we acknowledged that many people don’t get a chance to experience food trucks. So when we lined up Memorial Boulevard with food trucks for ManyFest, an end-of-summer street festival, tens of thousands of people showed up.

What would it take to shut down this street permanently? Perhaps it’s about showing the city the economic value — as you put food trucks in a designated area, that would possibly bring in new revenue and it creates pedestrian life. I also think it satisfies the inclusion piece — it’s visible, and people know that it’s there.

Gibson: You also could eliminate the conflict from business owners on Broadway.

What are some other ways in which design can support food trucks?

Gibson: Expand the width of the sidewalk and allow for more public space. Preserving and creating green space and maximizing the use of all sorts and sizes of land. Developers outside the city have bought many parking lots.

Retention of prime land is so important. There’s that event, SpaceLand, that a colleague of ours at HTFC helps plan. It transforms dead space and animates it with music, food, and so many great things.

These types of creative events give food trucks another way to pop up in the city.

Syvixay: Especially in the evening when all these parking lots are empty! In San Francisco, there’s an event called “Off the Grid” where food trucks “pop up” in different locations of the city, sometimes on the periphery, too.

People find out about this event through social media. When people arrive, they get to experience a vibrant and animated space, with beautiful signs that mark the space, bistro tables and chairs. There’s a lot of consideration to design and the experience for visitors. People feel like they can gather and stay for a long period of time.

Food trucks are often more temporary landscape infrastructure — they come and go during the busier summer seasons. How can design respond to this temporary quality?

Konrad: Portability, durability, and cost-effectiveness are important considerations. It’s important to support and purchase from local industries — so designs should be achieved with local designers, local manufacturers.

Maybe we can design a portable, stackable system that food truck operators can use to provide places for people to sit and enjoy. It can roll onto a flatbed, and then be transported to other cities and towns. The ease and efficiency will make it easy for food trucks to adopt and implement.

Reimer: I like the idea of working and collaborating with local businesses. Forth’s new patio build is a good example of this. It’s a custom design that you can’t buy online. They worked with someone local to build it to their specifications — to ensure that it engages not only their customers but also non-customers.

I love the design, people can sit inside or they can sit outside of the patio.

Syvixay: That’s what I like about the food trucks. You don’t necessarily have to buy anything from them. Now that food trucks have animated Broadway with activity, a walk down Broadway is mostly about being seen by others, being part of the buzz.

In San Francisco, for example, the city installed public parklets. You don’t need to buy product from the businesses that may be nearby.

And the businesses see the value of having people in front of their space, as they generate some excitement in the area and get people moving.

Konrad: And that element is good for business. It’s exposure, and it slowly orients people to being closer to the business.

Reimer: They appreciate the value of that, how it can generate more business.