On a bed of rails: Part 2 Dream of relocation clashes with reality of political will, price tag

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/09/2016 (3380 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is the second of a two-part series exploring how Winnipeg can co-exist with an entrenched railway system built a century ago. Read Part 1: Winnipeg’s past, present and future collide in relocation debate

Imagine a Winnipeg without rail lines.

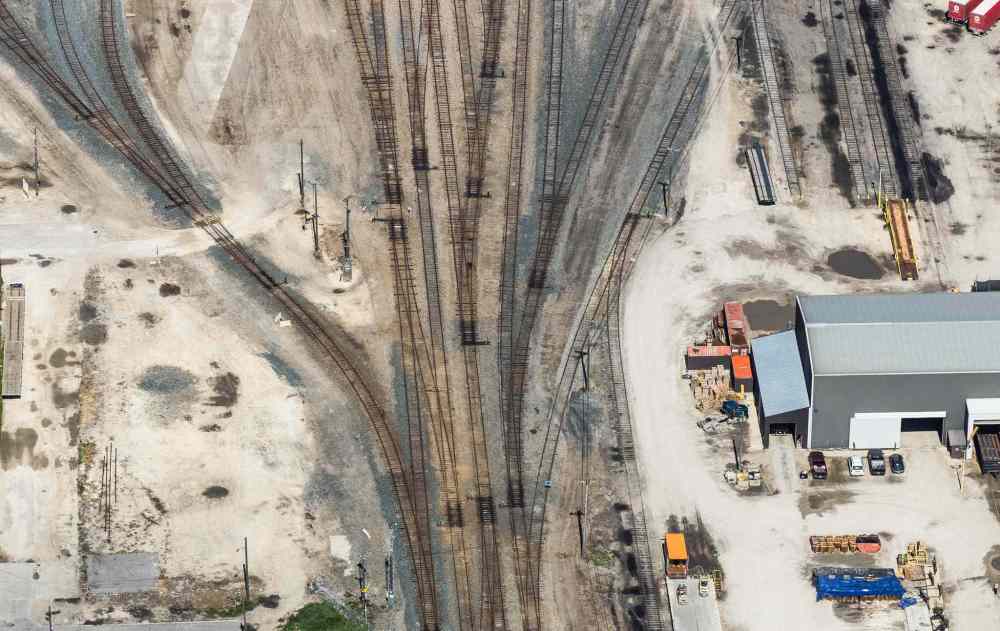

It’s circa 2035, and the Weston yards that have occupied the steel-lined landscape for more than a century have vanished and re-emerged as a new neighbourhood, complete with boutique shops and residential apartments. There is a sprawling park under the shadow of the Arlington Street Bridge.

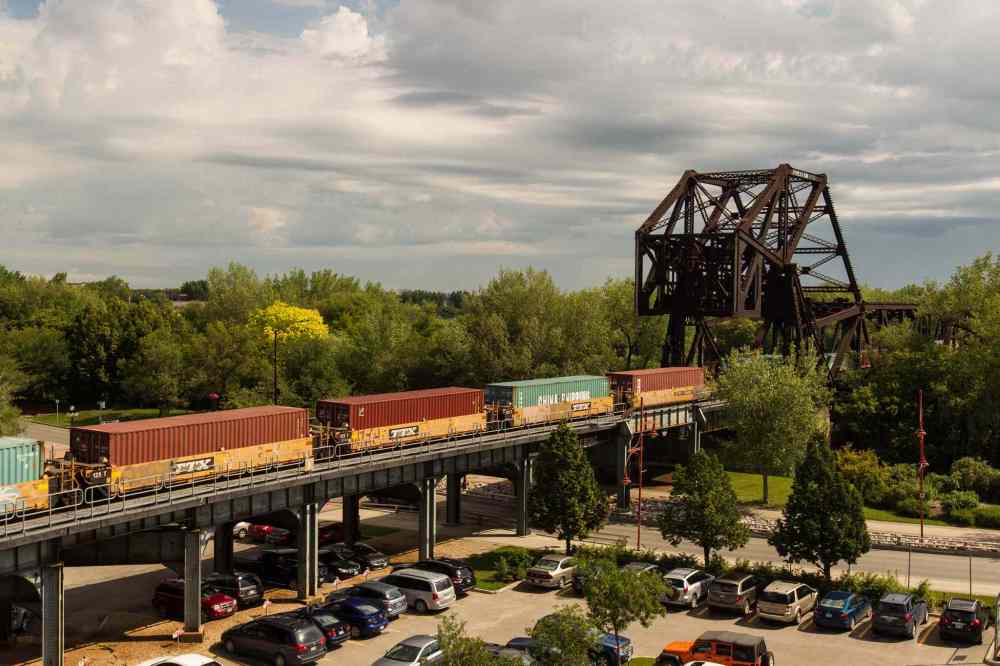

The original Canadian Pacific Railway line, which since 1885 has served as the Great Cultural Divide between north and south Winnipeg, is no more.

The two-kilometre-long trains disrupting commutes to and from the most populated suburbs are a bad memory. Over- and underpasses that were projected to cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars — and only getting more expensive with time — are no longer required.

The Canadian National line that snakes through the city’s heart is gone, eliminating the physical barrier between Main Street and The Forks. Abandoned lines have been converted to rapid transit corridors that stretch like spider webs from Main Street and Broadway’s revitalized Union Station to the city limits.

Is it conceivable? Sure, there are politicians, commuters and city planners who daydream at the notion.

“What sort of improvement could we do if we took all the money that governments and the railways are going to spend over the next 25 years and ask, ‘What can we accomplish?’” offered Saint Boniface—Saint Vital MP Dan Vandal, who, since his days as a city councillor, has championed rail relocation. “I think it’s a wonderful idea, but let’s make it more than an idea.”

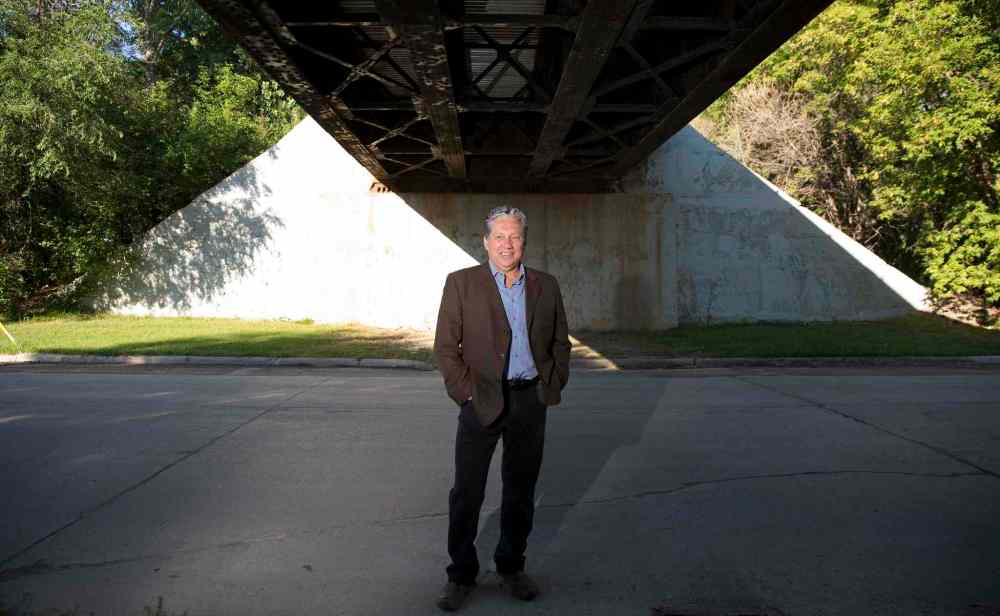

“One big move in 140 years,” added Winnipeg businessman Art DeFehr, the Palliser Furniture CEO who has long advocated rail relocation. “A clean city.”

Indeed, any relocation or rationalization of Canadian Pacific and Canadian National railway lines would mark a historic break with the city’s past.

Let the record show the first rail track in Winnipeg was laid in Saint Boniface — using the might of the Countess of Dufferin steam locomotive — and it stretched to St. Paul, Minn. The last spike was hammered on Dec. 5, 1878, to much civic flourish.

“The last rail is laid — the last spike driven!,” declared the Manitoba Daily Free Press. “Manitoba, after many vexatious delays… is now connected by rail communication with the outer world.”

Huzzah, right? But flash forward 138 years and the biggest question facing Saint Boniface in the 21st century is whether or not to build an underpass at Marion and Archibald Streets that local Coun. Matt Allard fears could cost upwards of $500 million.

“I want to find something else that would involve less expropriation, less cost and would enjoy support from the community, which this one does not,” Allard said in a recent interview, citing not just area but city-wide objections. “This is too big. It’s like killing a fly with a sledge hammer.”

Thanks a lot, Countess.

Sticker shock a sticking point

Winnipeg isn’t alone. Debates over rail relocation in urban centres are playing out across the country. From Montreal to Toronto, from Calgary to Edmonton.

In most cases, the circumstances are similar: the cost of over- and underpasses to allow trains to co-exist with vehicles is skyrocketing. Meanwhile, the price of inner-city land now occupied by rail right-of-ways is spiking (at least in Winnipeg) for the first time in decades. In other words, the extravagant cost of relocating tracks might now — and in the future — be offset by gains to municipalities of repurposing rail lines and yards and long-term savings in reduced infrastructure.

In January, the then-provincial NDP government announced a task force, headed by former Quebec premier Jean Charest, that was to spend the next two years coming up with the answers to the multimillion-dollar (up to multibillion-dollar) questions around rail relocation in Winnipeg.

Manitoba committed $400,000 to the task force. Then-premier Greg Selinger called moving the rail lines “a historic opportunity to reshape our city capital for the future.”

Not long after, Selinger’s NDP government was routed by Brian Pallister’s Conservatives in April’s provincial election.

Initially, Pallister was non-committal about the future of the Charest task force. When questioned about the Tories’ commitment to the study in early June, the premier’s response was ambiguous.

“I think it’s a great idea,” Pallister said. “It’s been a great idea for 40 years. And the NDP government did nothing about it in their entire 17-year term. Now they are telling me to get ‘Johnny-on-the-spot’ and take care of a problem they ignored for two decades? C’mon. Let’s be real here.”

Last week, the Pallister government cancelled the study.

“Manitoba’s new government was elected… to fix the province’s finances, and therefore we will not be proceeding with the task force,” Indigenous and Municipal Relations Minister Eileen Clarke said.

Prior to the government’s decision, Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman said he is a proponent on moving forward with the task force, if only to get “accurate information on (whether) the cost is something that would benefit the discussion.”

“The first step is getting some numbers so we have a better idea of what we’re talking about,” the mayor told the Free Press recently.

Bowman reiterated his position several days after Pallister’s decision. Bowman is hopeful he can convince provincial and federal officials to revisit the topic, with Ottawa helping to cover the cost.

Vandal, who was to represent the federal government on the task force, was also realistic prior to the government’s decision, suggesting Pallister might not have the same sort of excitement for the project.

The short answer is no.

Selinger has for decades championed rail relocation, in particular the Weston yards, back to his days as a community activist in the 1980s. On the eve of his government’s defeat, Selinger acknowledged a Pallister government could have a “dramatic impact” on the task force. “They could cancel it tomorrow if they want to,” he said.

If anything, the change in provincial government only underlines the difficulties in addressing generational projects such as rail relocation. The federal Liberal government ran on a platform of infrastructure spending, which could include moving rail in urban areas. Bowman has at least expressed support for investigating a cost-benefit analysis.

And not only were all three levels of government on board with the Charest task force, but both CN and CP had agreed to participate.

Selinger argues, regardless of any task forces or public debates, the issue of rail in urbanized settings isn’t going away.

“We’re back in the same dilemma,” he said. “The infrastructure is really old that goes over and under railways. There’s going to be a big bill that has to be paid to address that. Rather than pay that bill — bridge by bridge, underpass by underpass — the opportunity to look at a big decision could save hundreds of millions of dollars on infrastructure.

“There is a point where the do-nothing option poses hundreds of millions of dollars in costs for renewing existing infrastructure. That is the inflection point to look at a more global approach to change and urban renewal.

“It’s more realistic now that it’s ever been,” Selinger said. “And we need the leadership to move it forward. And the railways are not saying no. Without that political will, it ain’t happening.”

And that’s the rub: Pallister was right in saying the NDP government was in power for 17 years and only in the waning days of their reign was the task force announced. So what held even a noted proponent such as Selinger back?

One long-time NDP insider suggested, perhaps tellingly, it wasn’t the political will of the NDP that stalled rail relocation: it was the perceived lack of will on the part of taxpayers who might blanch at the up-front cost estimates, with little or no guarantee of future payback.

Even Selinger conceded: “Everybody likes the idea of rail relocation. But people are quite skeptical of the feasibility. And sticker shock is one of the big things. It’s like, I’d love to buy a Cadillac but I ain’t buying a Cadillac, right?”

For example, the immensity of moving the CP Weston yards — regardless of the cost of rebuilding the Arlington Street Bridge or the long-held belief the rail lines have been a literal economic divide between north and south — has historically been a roadblock to concrete action.

As far back as 1972, the city has been debating rail relocation of the CP yards. Nothing happened. In 1980, the federal government pegged the cost of moving the main line and the marshalling yards at $169 million over five years and the future cost of overpasses and bridges at $65 million. Nothing happened.

In June 2016, a study on replacing the Arlington Street Bridge — built in 1912 and recommended to be decommissioned by 2020 — estimated the cost at $300 million. The study alone cost $2 million.

There are those, such as prominent Winnipeg businessman and longtime relocation proponent Art DeFehr, who will resist the notion relocating the CP yards and track will cost in the billions, if only because no serious cost study has ever been done.

“It’s not going to cost billions,” DeFehr said, during an interview at his furniture company headquarters in Transcona. “Why would anybody say that?”

Last year, DeFehr produced a five-page position paper that estimated relocation cost at $1 billion by constructing a track south of Winnipeg, from Elie to south of Oak Bluff, then south of the Winnipeg floodway back up to the existing main line.

“It’s almost empty there,” Fehr said. “You could run a 10-line highway through there and hit five houses. Winnipeg is the only place in Canada where there’s a pathway around the city with nothing on it. But we have no imagination. They don’t spend their time even think about it. We’re talking about underpasses.”

The Weston yards, said DeFehr, could be relocated along the new line near Oak Bluff.

But even the best plans for laid track around the city are inconsequential without extensively studied proposals that would take years to develop. The Charest task force, had it been implemented, would have taken at least two years to present credible cost-benefit analysis.

Because it should be noted while it’s often assumed major rail companies, such as CN and CP, are steadfastly opposed to any relocation, it’s incumbent on the local governments to produce a feasible relocation plan.

Indeed, CP’s standard position on relocation is even posted on its website: if a community wants to move the lines, CP “may” participate. “However, the relocation of rail lines and yards is a complex and serious issue that would involve CP, local and national customers, regulators, local community organizers and all levels of government.”

According to the federal Railway Relocation and Crossing Act, established in 1985, the Canadian Transportation Agency has the power to order companies to relocate, but only on the condition “a rail company must not gain or lose financially by moving. Relocating must be a break-even proposition for the rail companies.”

The federal government’s contribution to relocation costs, including studies and planning, is capped at 50 per cent. The CTA can also make orders determining who pays what for relocation, based on “accurate financial information” that must be provided by the city, province and rail companies.

Tracks in Canadian cities

Free Press requests to interview executives with both CN and CP were declined. However, Michael Bourque, president and CEO of Railway Association of Canada, which represents both railways, said the potential cost of significant rail relocation, although yet to be accurately determined, would present a challenge.

“You’re really talking about a giant project, in the case of Winnipeg… therefore that’s going to be many billions of dollars,” Bourque said. “Then the city has to ask themselves: where are they going to find that money and is that the best use of that kind of (tax) money? Is that what society would want to spend that money on?”

▣ ▣ ▣

Efficiency equals velocity

So how much power do the railways have when it comes to relocation? Or, rather, not relocating?

“Lots,” said Harry Finnigan, Winnipeg’s former chief planner who now is a partner in MacKay Finnigan Associates, consultants for urban redevelopment. “They really don’t need to do much if they don’t want to do it. Certainly, they have way more power than any other corporation that a municipality or any level of government has to try to work with.”

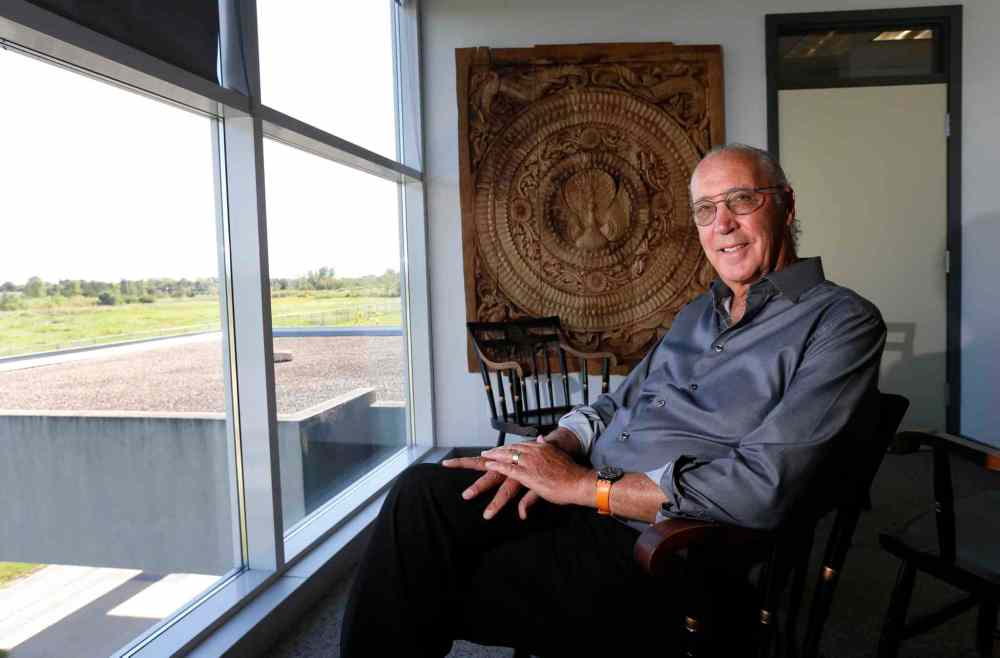

Diane Gray, CEO of CentrePort Canada, a 20,000-acre transportation hub in northwest Winnipeg designed to attract rail-intensive business, noted railways “are probably more powerful than the average layperson can imagine.”

“And that is because they largely pre-existed most western (city and provincial) governments,” Gray said. “And their corridors and right-of-ways are pretty much sacrosanct. To assume governments could force them to do what they don’t want to do… they will respond vigorously to protect their own interests. They will not give up corridors without there being a better solution. And they don’t have to.”

At the same time, Finnigan and Gray believe with the evolving nature of rail transport — where yards are not nearly as active and more trains are simply passing through urban centres — management at CN or CP should be more open to any proposal that speeds delivery.

“It would be good to know what portion of goods that are transported through our city are intended to stay in our city,” Finnigan said. “I would think, compared to 40, 50 years ago, it’s a lot less percentage than it is now. So, fundamentally, what’s the need for them to go through the city from a business perspective? It would probably be advantageous for them to go around the city, just like trucks using the Perimeter Highway.

“I’ve got to think there will be a benefit for them (railways) if so much of their tonnage is not destined for businesses or customers in Winnipeg. They’re just going through the city and they have to slow down.”

Added Gray: “They want to build and run long trains quickly. That’s where they make their money.”

Yet, every single CN train that travels across the country must slow to a crawl while navigating the elevated line that passes through The Forks. Every. Single. Train.

So despite his reservations about relocation, even Bourque acknowledges speed is essential in rail transportation.

“In theory, if someone can create a railway that goes around, that is going to be quicker… and be made whole for that, sure,” he said. “Railways would be in favour of that. That’s why we’ll always have that discussion.

“At some point, these things become practical for a variety of reasons; because of density, because of opportunity,” Bourque said. “In the railway business, efficiency equals velocity. Railways want their trains to run from point A to point B quicker because that’s what gives them an advantage over trucking.”

So what are the city’s options? One is to start small.

Gray believes focusing first on major projects such as the Weston yards — because of the enormity of the task — might work against any relocation effort.

“I like the idea of success and momentum… rather than biting off the biggest problem first and having everyone stymied by it,” Gray said. “It makes all parties not only look good, but progress can be made. And trust can be built without having to go to the full-meal deal all at once.

“We are dealing with three different private rail companies here and they’re competitors. All of this isn’t a slam dunk. There’s going to have to be wins for everyone. It won’t be that simple.”

One example of small-scale relocation, according to advocates, would be the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe spur line that now runs between Taylor and Corydon avenues along Lindsay Street in River Heights.

Local residents balked a few years ago when BNFS Railway erected silos along the line to store water used to spread over dirt roads outside the city limits.

“They want to do industrial activity and it’s all residential around them,” said River Heights—Fort Garry Coun. John Orlikow. “That’s a problem that occurs.”

Orlikow wants the spur line relocated outside to city to the inland port.

“Really what they (BNSF) need to do is get to CentrePort,” Orlikow said. “They would be more successful. CentrePort would be more successful. They don’t want to be there either. They don’t want to drive into the city and drive back out again. They just don’t have many alternatives.”

Orlikow and provincial officials have been working with BNSF on an alternate route on an existing CN line for months now, with no results. The councillor remains confident an agreement can be reached.

And what would occupy that space if the lines were removed?

“All of us dream and we do it well,” Orlikow said. “There’s lots of opportunities to really benefit the neighbourhood.”

Maybe a dog park. A bicycle path. An urban forest.

Orlikow believes similar opportunities to relocate and redevelop spur lines exist elsewhere.

“The grand vision, that’s wonderful,” he said. “I’m very excited to look at the number of spur lines opening up opportunities for green space development or whatever. I’d love if all the lines could go around the city but eventually we’re going to grow out there, too.”

Chief city planner Braden Smith isn’t opposed to plans to move the Weston yards. Just not as the first order of business.

“Exactly,” Smith said. “The reality is… from a planning perspective, the City of Winnipeg is a slow-to-moderate growth community. So it’s good to look at the monumental fixes for land-use issues. But my approach is… I think it’s the small and incremental changes that we need that actually pay the largest dividends in the long run.

“I mean, we can talk pie-in-the-sky and teddy bears and lollipops. But my focus is on what are some of those low-hanging fruits.”

Which begs the question: if a city planner could pick one rail relocation project in Winnipeg, what would that be?

For Smith, the answer is The Forks: transforming the existing CN rail lines not being used at Union Station into a rapid transit bus corridor.

“I think there’s some synergies there. I think that’s a great opportunity,” Smith said. “We’ve got this wonderful Via station. Using it as a main hub for downtown would be interesting, I think. It could really act as a catalyst because it’s a beautiful building as well.”

Such a project could merge with the southwest rapid transit corridor, linking Union Station with the University of Manitoba. Future lines could stretch in all directions, making the refurbished, 105-year-old station a central transportation hub of the city again.

▣ ▣ ▣

A paradox

Meanwhile, Bill Menzies, former manager of service development for Winnipeg Transit, relishes the idea of removing the so-called CN Hi-Line that snakes through The Forks, past Shaw Park, then across the Red River into Saint Boniface.

Menzies, who spent 32 years with the city, said relocating the line would eliminate the physical barrier between Main Street and The Forks.

“That would be awesome,” he said from a downtown apartment that overlooks The Forks. “I don’t know if it would be in my lifetime. It depends on the political will. These things take a long time.”

Menzies should know. He worked extensively in making the southwest rapid transit project a reality. Menzies was first handed the project by mayor Bill Norrie in 1990. The first phase was completed in 2012.

Perhaps that’s why Menzies isn’t shy about relocating the Weston yards under the Arlington Street Bridge, either. Because he can envision what redeploying rail lines in the city could accomplishment for rapid transit potential. Or even just potential development, period.

“There’s a lot of land there and a huge city-building potential,” he said. “Not only physical development of the city but social development. Those lines right now are a big barrier.

“(But) things like that are pretty transformative. It’s probably going to be a multi-decade endeavour — if it’s affordable, feasible and everybody is on board.”

That’s the paradox of the prospect of rail relocation in Winnipeg: it’s difficult to find a politician of any stripe who is dead set against some form of the concept. It is generally considered safer, less intrusive on day-to-day city life, better connects neighbourhoods and opens up a number of recreational, residential and business development opportunities.

Even the railways don’t deny skirting populated areas would be good for business.

At the same time, the general consensus among those in the rail industry, or related ventures, is the same forces putting pressure on relocation — urban sprawl and rail traffic within city limits — will continue to trend up.

“There’s going to be rail growth whether you like it or not,” said CentrePort vice-president of marketing and communications Riva Harrison. “We’re a rail city. So you might as well do it in a way that makes strategic sense and doesn’t add to your woes.”

Added Gray: “We don’t need rail rationalization or relocation to occur for CentrePort to happen. It’s happening regardless. But I do believe the time is right for the community — and that means government at all levels, rail companies and shippers — to look at the broader issue of the future of Winnipeg as a rail city.

“What does a modern Winnipeg look like as a rail city, is the question before the community.”

But ask those same players if progress on potential relocation can be made, the answer is far less decisive.

“My guess is it will come down to political and community will… even if it’s incremental over time, something will happen. If there isn’t, well, then it won’t,” Gray said.

“There’s a lot community support for the issue. But I also believe there’s a lot of skepticism about the ability to pull anything concrete off. With big changes, there’s always going to be sticker shock. But if we don’t make any changes there’s going to be other infrastructure big-ticket items that are going to have to be paid for. (And) there’s going to be more of that over time, not less.”

Finnigan, the former city planner, doesn’t need to be convinced of the potential for relocation or rationalizing of rail. After all, it was during his tenure with the city The Forks was developed on land that once served as the city’s largest rail yard.

Today, The Forks is widely considered the most successful developments in a generation — and that’s not including the planned development of an urban community behind Union Station. Winnipeggers gather at The Forks by the thousands every year. They hold celebrations. They skate on river trails. They eat in pop-up winter restaurants. They shop at markets that were once railway company stables.

“There’s got to be a better use for that land,” Finnigan said. “You’ve got a right-of-way from one point of the city to another. It’s a natural for transit.”

Brent Bellamy, architect and creative director at Number Ten Architectural Group, argued relocating rail, especially in developed areas of the city, would help curtail urban sprawl.

“We all know the city is broke and can’t afford to balance its books anymore,” said Bellamy, recently named to the board of CentreVenture Development Corp. “Our roads are crumbling and services are being cut, fees and taxes are increasing. This is due in very large part to the way the city has sprawled. The city has grown by three-quarters in area since 1970 but only one-third in population. That lower density has made the city unsustainable.

“Infill growth is the only solution. (Relocating) the rail lines and yards provide a major opportunity to achieve this. Imagine what a large new residential population would do for the businesses of the North and West End. What about the lines in River Heights and Tuxedo? How much would the tax base grow if those prime lands were allowed to be redeveloped?

“It could be the anchor of a rejuvenated North End that rarely sees investment.”

Relocation would also mean less noise, less air and ground pollution, improved traffic circulation and reduced risk of accidents and derailment, he said.

At the very least, Bellamy and Finnigan argue before the city becomes too invested in going over or under the rail, the relocation task force — in some form — should not be abandoned.

“It may be in spite of everything nothing changes,” Finnigan said. “It’s such a complicated issue, it hasn’t been dealt with. But I think it’s worth having that discussion. If there’s a will, there’s a way. But it’s got to be based on proper data.

“So I hope there will be some resources that go into getting that information. Just not throwing your hands up and saying, ‘Well, it’s way too complicated’ and ‘The railways won’t budge anyway, so let’s not even go there.’ I think that’s what’s happened, generally, in the past.”

That’s always the caveat, even from relocation proponents: without proof, relocation can ultimately be profitable — not just for the city, governments and taxpayers, but equally for the railways — what’s the point? The rest is just theory and hope.

Meanwhile, planners and city councillors face immediate infrastructure updates, such as road maintenance, sewer and water line upgrades, and funding community centres. Facing ever-growing deficits and service cuts, rail relocation might seem like a luxury, if not a financial impossibility.

Barry Prentice, a professor at the Transportation Institute at the University of Manitoba, wouldn’t deny those realities. But he has his own, too.

Prentice is a staunch defender of the economic value of railways and their integral place in the city’s history. But he also believes while the city’s past was defined by railways running through its core, its future health depends on their removal.

“I know it’s in the millions of dollars,” Prentice said. “But the argument is, and I support the notion, that it’s going to happen eventually. Those right-of-ways are very valuable for moving people, whether it’s rapid transit or LRT, whatever it is. That’s the future of our city. So sooner is much better than later because it will never get less expensive.

“It also means the sooner we do it, the more the city will grow and adjust to the new environment without the railways.”

How can a city plan significant rail relocation for tomorrow while at the same time debating and deciding today about over/underpasses that are projected to cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars?

To wit, why build underpasses at Marion Street and Waverley Avenue — with a combined estimated cost of upwards of $800 million — then turn around and pay even more to relocate those same rail tracks 10 years in the future? By the time they are completed, the two phases of the Arlington Street Bridge project (phase 2 is either a tunnel between Sherbrook and McGregor streets or reconstruct the McPhillips Street underpass) could total $1 billion alone. What? Then rip out the CPR yards?

So many questions, so few definitive answers. Which might explain why after years of hypothetical and fruitless debates, Vandal is growing weary.

“To be honest, I’m tired of talking about it,” the MP said. “We need some facts and we need a strategic plan to see if it can be done. As long as I remember, we’ve been talking about it but nobody has any germane facts at their fingertips.

“We need to look at the capital budgets of all three governments, and by that I mean how much money is the city going to spend on infrastructure over the next 10, 15 years? How much money is the federal government going to spend on the City of Winnipeg? Same with the province. And then look at the private rail lines. How much are they going to spend reconstructing, modernizing their infrastructure?

“That’s where it begins,” Vandal said. “Let’s get some facts in front of us… and see if it’s something that’s doable on paper. Take away all the political intangibles. Let’s just look at the numbers and what can be done.

“If it makes sense, I’m as hard-core as anybody. If it doesn’t make sense, let’s move on.”

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, September 18, 2016 2:34 PM CDT: Corrects typo