Heartbeat of a small town Community survival depends on the vitality of the local hockey rink By: Randy Turner Posted: Last Modified:

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/02/2016 (3585 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

FOXWARREN — It’s Saturday afternoon and the old barn is alive. For now, anyway.

The parking lot is jammed. Inside, the 65-year-old arena is lousy with kids, most of them half-dressed in hockey gear. A boy in goalie equipment is standing at the cafeteria window ordering a piece of apple pie.

The air is filled with squeals of children and the aroma of sweat that seems to have permeated the Foxwarren building over decades — not unlike any other aging small-town hockey rink on the Prairies.

For those raised in these endangered buildings, it’s the smell of home.

In the cafeteria, Bev Wotton is dishing up her homemade perogies while her two sons — Mark and Scott, both former high-level hockey players — are behind the bench coaching their sons’ peewee team.

The rural hockey circle of life.

“So, yeah,” the silver-haired matriarch says, “we’ve spent a little time here.”

On a recent weekend, a Free Press reporter and photographer set off on a whirlwind tour of rural hockey rinks in Manitoba — 10 communities and more than 1,200 kilometres. The purpose? To discover the unique connection between the game and the arenas that, for decades, have served as the beating heart of their hometowns.

After all, these are the buildings of shared memories — where little boys and girls take their first strides, where fierce rivalries with neighbouring towns are fought, and where so many NHL careers have been born.

“You guys have a great job,” Clare Jago, president of the Manitou Community Arena, tells us during an early stop. “Going around the province to see all the best churches.”

Churches?

He smiles.

“That’s where everybody gathers on Sunday,” Jago replies. “At the rinks.”

Truth be told, it’s not just Sunday.

Bev Wotton will tell you it’s a full-time job keeping these rinks open. Always has been. And every year, it gets a little harder.

Towns are shrinking. Arenas are closing. Senior and minor hockey teams are either disappearing or forced to amalgamate to survive.

In Foxwarren, located about 320 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, where there was once 200 children in the town’s school in the 1960s, there is no school at all. The four grocery stores, five elevators and bank have long since closed. The Foxwarren Falcons senior team, which once dominated the North Central Hockey League, has been defunct for two years.

But if you ask Wotton if she could imagine her town without a hockey rink, she almost looks hurt.

“Oh, I could never,” she says, as her grandsons leave the ice to join the noisy fray in the arena lobby. “There’s just so many memories through the years. It has always been the heart of the community.”

Wotton pauses for a moment. Look closely and you can see the tears welling in her eyes.

***

Lenore

3 important buildings: Church, hall, rink

The only thing missing from the Lenore Community Arena on a recent weekend was, well, hockey.

For the record, Lenore, a tiny hamlet just northeast of Virden, is a postcard of a small prairie community in repose: a lone weather-beaten elevator, an abandoned Gulf station and a smattering of old homes.

But wait. Something is stirring in the metal-coated building that abuts the prairie.

Inside, a group of men have converged on the rink’s ice surface, which has been converted into curling sheets for the Lenore bonspiel, an annual event of legendary frivolity.

Down the street is what the locals call Chic’s Place, a residence once owned by a man by the same name who, upon his passing, bequeathed the home to the community.

On bonspiel weekend, Chic’s Place is transformed into a speakeasy, of sorts.

There is a list of rules posted at the door. Rule No. 1: “Hours of operations: Endless.”

The entire operation is small-town ingenuity at work. Need more curling sheets? Paint rings on the hockey rink surface. Need a place to imbibe away from the kids? Hello, Chic’s Place. (This may explain why the now-defunct senior hockey team in Lenore was named after a brand of whisky, the Five Stars. But we digress.)

The Lenore arena was built in 1949 — like so many others that rose from the Prairies after the Second World War — and stands adjacent to the curling rink, still the home to a healthy 26 club teams.

There is only recreational skating in Lenore, however. No hockey teams.

And the money raised by the bonspiel and community supper that Saturday evening will (hopefully) be enough to keep the doors open for another winter.

“That’s the goal, obviously,” says arena treasurer Keith Gardener. “It’s huge. Just for the community, period. It’s just a place that kids can come and go out and play.

“In the town we have three important buildings (left): the church, the hall and the rink.”

***

Hockey life

Rink plays ‘host to the neighbours’

For most small Prairie towns, that has always been the three pillars, socially speaking. The churches and halls came first, but by the late 1880s, the hockey arenas (and the oft-attached curling clubs) were in full bloom.

According to former Brandon University history professor Morris Mott, hockey’s popularity mushroomed with junior and senior teams forming in dozens of communities between 1899 and 1909, when, for example, the first rink opened in Foxwarren.

And Manitou and Souris and Virden and Boissevain and Oak Lake and Reston or pretty much any town with a taste for a physical winter sport that allowed young farm boys to challenge the next group of farm boys down the dirt road.

At first, the rinks were outdoors. A few, Mott says, had a roof that was held up by poles players had to stickhandle around. In Dauphin and Cypress River, hockey was played on a skating oval that surrounded curling sheets.

Eventually, facilities became more uniform in size and ice surface, although most were still undersized by today’s standards.

“In all the agricultural prairies, they had similar buildings,” Mott says. “And a lot of them now have become… used 12 months of the year, more than they were in the early days. Now they’ve become community centres. They’re used for fairs and bake sales and theatrical productions. A lot of different things. When I was a kid, they were just winter centres.”

Mott’s experience isn’t just academic. Raised in southeastern Saskatchewan, he grew up playing in small towns — at least until he joined the Canadian national team in the late 1960s, then moved on to play three seasons in the early 1970s with the NHL’s California Golden Seals.

Mott grew up playing against future NHL players such as Bill Lesuk, Larry Hornung, Dave (Tiger) Williams and (Cowboy) Bill Flett. All prairie boys.

Now 69, Mott came to realize at an early age the dynamic between hockey teams and their towns — and, by extension, the place where games unfolded.

“Hockey has a greater spectator role,” he says. “The town identifies with the team and shows up eight, 10, 12 times a year — however many games there are. So the hockey rink has a greater role in the community strength, if you could call it that.”

Hence, the determination among residents in most rural communities to ensure the local arena not only remains viable, but a tangible expression of health. After all, the schools, churches and town halls are for locals. It’s the hockey rink that plays host to the neighbours.

In fact, if there was one overriding observation from a cross-section of the 10 communities visited, it was the concerted community efforts to renovate the local arenas.

***

Manitou

‘Hub of our community’

In Manitou (motto: More Than a Small Town), residents recently spent $680,000 to upgrade a facility that cost $250,000 to build in 1973. There’s a new kitchen, overhauled spectator area and theatre seats behind a new bank of Plexiglas.

“If you don’t upgrade… the buildings are going to let go sooner or later the longer you leave them,” says Jago, the arena manager. “And nowadays it costs a considerable amount of money to do any upgrades. So the longer you leave it…

“This is the hub of our community,” he adds. “This is the only arena in the municipality that’s used for minor hockey (about 60 kids in total). So it’s a huge, busy place for everything.”

Walter Mueller, 78, was mayor of Manitou for 15 years. His younger brother, Lewis, was a member of the 1959 Memorial Cup champion Winnipeg Braves, and former defensive partner of NHL great Bill Juzda.

Lewis was invited to the Detroit Red Wings training camp in the early 1960s, but decided to stay in Manitou (population approximately 800) and work at his father’s hardware store.

“Maybe I didn’t feel so comfortable going so far away,” Mueller says. “I guess most kids would have gone but…”

Mueller would have gone in a heartbeat. “If we changed names,” he says, “I would ride my bike (to Detroit).”

The Mueller boys both played senior hockey in Manitou, in an ancient wooden arena that was turned into a stock barn after it was put out to pasture in 1973.

“There’s some real ice palaces in the country now,” Mueller says. “I used to play in rinks, if you looked back right now, they were barns.”

The current rink is now home to a seniors exercise area and community yoga classes. (Jago proudly points to the wheelchair access.)

In addition, volunteers built an outdoor rink a few years ago, raising more than $30,000 in donations, just to give kids a place to play shinny when the arena is otherwise booked.

“It’s a community thing, that’s what it is,” Mueller says, when asked about the priority given to the facility. “If you didn’t have it, you’d have to go to the next town.”

It’s true.

***

Pilot Mound

‘We’re lucky for a small town’

It was the hockey rink that lured Rod Collins back.

“This is my hometown,” Collins says. “I’ve got family here. Maybe give something back to the community that’s served me so well. You’re coming back to share something from the town you came from. That’s important.”

Collins, 70, is standing on the second balcony (yes, balcony) overlooking the ice surface of the Black Jack Stewart Memorial Arena — itself a testament to the lengths a community will go to preserve its hockey heritage.

It took more than a decade to construct the arena, which was moved piece by piece from the abandoned northern Manitoba Hydro community of Sundance and put back together in this farming community some two hours southwest of Winnipeg.

But the arena was just the start. The Pilot Mound Millennial Recreation Complex, built at a cost of $3.5 million, also houses the adjacent curling club. It will soon be home to the town’s library and museum. The Tivoli movie theatre, slated to open next year, is under the same roof.

“It’s amazing to have a facility like this,” Collins says. “The intriguing thing about this was it was all done pretty much voluntarily. And the fundraising continues.”

As a young man, Collins was one of four brothers who played for the Pilot Mound Pilots, the town’s senior team. He went on to become a coach and instructor at two of North America’s most prestigious hockey academies: Notre Dame in Saskatchewan and Minnesota’s Shattuck-St. Mary’s.

When the Pilot Mound complex became a reality, Collins was inspired: why not develop a hockey academy in Manitoba that might one day rival those that produced the likes of NHL stars Wendel Clark and Rod Brind’Amour (Notre Dame) and Sidney Crosby and Jonathan Toews (Shattuck)?

“I always had that idea,” says Collins, whose daughter, Delaney, is a former member of the women’s national hockey program. “And knowing this facility here, with the small town that was supportive, that this would be the ideal place for the development of kids.”

Today, the dressing room of the Pilot Mound hockey academy is filled with 19 players from Wisconsin, Colorado, Finland, Ukraine and Slovakia. Oh, and also Pine Falls and Pilot Mound.

“For me, it wasn’t a big adjustment,” says Will Lovell, a 17-year-old from nearby Manitou. “But it’s nice to have the academy close to home. We’re lucky for a small town. Even bigger centres don’t have as nice a rink as we do.”

The annual cost for the 10-month program — now in its second year of operation — is about $26,000. That includes room and board at local billets, travel (the team has already competed in Germany and just returned from a tournament in Anaheim, Calif.) and most equipment.

Collins estimates the program injects about $200,000 annually into the local economy, with $100,000 in billet fees alone. Since the players are also students, enrolment at Pilot Mound Collegiate jumped to 98 from around 80.

The positive impact on school numbers has those who have partnered in the academy envisioning a program that could be expanded to include a female team and another for younger males.

Big North American cities aren’t the only communities that envision hockey arenas as potential economic drivers. And Pilot Mound wasn’t the only place on our journey where we found a man returning to his hockey roots.

***

Waywayseecappo

‘The only real entertainment in the area’

In Waywayseecappo, a First Nations community 30 kilometres east of Russell in western Manitoba, Barry Butler is found going over the game plan with yet another clutch of young men chasing their hockey dreams.

The Waywayseecappo Wolverines aren’t having a good year. The Manitoba Junior Hockey League team was 13-32-4 when we visited, and head coach Butler was clinging to the hope of a late-season surge.

Butler was born and raised on a farm near Foxwarren. He was head coach of the Wolverines when they were originally founded in 1999, then later left to coach a North American Hockey League junior team in Cleveland. (One of his players was future Winnipeg Jets forward Jim Slater, who was drafted by the Atlanta Thrashers right out of the Cleveland program.)

When Butler returned home for a visit about a dozen years ago, he found the Wolverines in disarray. Players were sharing sticks during games. Waywayseecappo Chief Murray Clearsky, who invited Butler to a game in which the Wolverines were losing 14-1 after the first period, asked: “Can you help?”

Butler has been in Waywayseecappo ever since.

The Wolverines are still struggling, but Butler remains motivated by Clearsky’s original vision, which was to build the arena and develop a junior team that can tally both pragmatic and economic goals.

“It’s not only for my community, but the surrounding community,” Clearsky says. “I would say it’s 50-50 (fan base) going to the hockey games. It’s the only real entertainment in the area.

“They all mix. They have a better understanding of each other.”

Adds Butler: “(Clearsky) wanted to break down barriers. That’s what it’s about. That’s the goal.”

But attempting to run a junior team — the Wolverines are a collection of players from Winnipeg to Connecticut to Minnesota — has its challenges.

“It’s more difficult, that’s for sure,” Butler says. “For teams near the city, it’s a lot easier. We used to say if you want a Tim Hortons and A&W, this is not the place to be.

“But then,” the coach smiles, “Russell got a Tim Hortons.”

The Wolverines might be the only junior club that raises funds by renting out land (donated by the band) to local farmers and selling hay baled by the head coach himself. Whatever it takes, right?

Has it worked? Well, there is still hockey in Waywayseecappo that attracts some 400 to 500 fans a game. And the club has an alumni that includes Binscarth’s Cody McLeod, now assistant captain of the NHL’s Colorado Avalanche, and Sean Collins, drafted off the Wolverines by the NHL’s Columbus Blue Jackets in 2008.

Then there’s Dylan Tanner, a Wolverines rookie who was born in Waywayseecappo when the arena was being built in 1998. Along with his older brother, Montana, Tanner was a fixture at the rink growing up. He remembers where he was standing during the Wolverines most memorable victories.

“We were watching this team hoping one year to play,” he says. “Now I am.”

Montana was a Wolverine, too.

“This team has brought the community together, watching hockey,” Dylan Tanner says. “Friends and family coming out. A lot of elders come out.

“It’s an honour. I’m finally getting a chance so I’m going to make the most of it.”

***

Kenton

‘Pride of a small town’

Blair Fordyce didn’t mind meeting a couple strangers on short notice, even if it was a Saturday morning.

“It’s OK,” he says. “It’s my day to work.”

Fordyce is one of seven volunteers who each spend a day of the week tending to the Kenton Arena, home of the Cougars. On a recent Saturday, Fordyce was flooding the ice.

For the uninitiated, the Cougars are a local senior team that has been toiling in the North Central Hockey League since it was established in 1971. However, in a league where there was once upwards of 14 teams, there are now six.

And the Kenton Cougars are 2-15.

Fordyce was a Cougar for 17 years, from inception to the late 1980s, a time when the club captured nine provincial titles (D and E divisions). Home games at the arena would attract crowds of up to 200, larger than the town’s population.

Forget the NHL’s Winnipeg Jets, this, folks, is a small-market team.

“All local guys, there was more interest,” Fordyce says. “And there was more people around, too. Everybody came to the rink. When we started we’d have people drive 160 kilometres to watch us play.”

Once, the Cougars could ice a team with players from a 25-km radius. Now it’s closer to 80 km.

“The whole philosophy of hockey has changed,” says Fordyce, 59.

“More people go to rec hockey right out of high school because there’s so much travel. We like to win the same as anybody else, but we give a place for kids to come and play.”

There is no minor hockey in Kenton. So keeping the rink open largely for a senior team stocked with players from Brandon, Oak River and Rivers is a conscious effort to preserve a piece of the town’s history.

“It’s just the pride of a small town,” Fordyce says, “having a hockey team.”

That last sentence shouldn’t be lost on Winnipeg hockey fans who once lost the Jets.

Why? Because there was a time, not so long ago, when the senior team — made up of teachers, farmers, RCMP officers and local merchants, among others — was the small town’s NHL.

They played before packed arenas. They had media coverage — weekly newspapers and, in some cases, radio broadcasts. Their exploits were the coffee-shop chatter of the next morning.

“When you were growing up, some of your idols were on that team,” Mark Wotton says of his youthful days of watching the Foxwarren Falcons. “As much as guys you watched on TV in the NHL.”

When the Falcons would battle the arch-rival St. Lazare Outlaws, for example, it would be standing-room only in both towns.

“The rinks were full. Lot of excitement,” he recalls. “Everybody was taking about it. Everybody was there. That was your NHL game.”

Wotton should know. He grew up to play in the NHL — a total of 43 games with the Vancouver Canucks and Dallas Stars — during a 15-plus year professional career in the AHL, IHL and KHL.

But if Wotton’s experience as a Falcons stickboy in the 1980s was etched in his young brain, imagine the atmosphere in rural arenas during the glory days of senior hockey in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. There were no 60-inch HD television screens, no NHL Network, no NHL Jets. There was just “Farmer’s TV,” one channel at first with just Hockey Night in Canada on Saturday night.

“(Senior hockey) was a focal point,” says Brian Franklin, a former president of Hockey Manitoba. “Back then, you didn’t have the Ski-Doos. There was no skiing. So really, in the winter time, there wasn’t a heck of a lot of anything. Other than the arena.”The old rink, they’d put 1,200 people in there and the girls used to come up and down the boards and serve coffee because it was so jammed. To me, that was like the Big Apple when I was a kid, watching the senior team play. That was everyone’s ambition growing up in a small town.

Rob Collins, head coach and general manager for the Pilot Mound Buffaloes.

For Franklin, it was the Deloraine arena and the hometown Royals. Like most children of small towns, he can still recite by heart the names of the team’s star players.

“It was big time,” he says. “The senior team was the thing in town. Kids thought about growing up to play for the Royals. Everybody knows everybody in a small community anyways. But you were looked up to, that’s for sure. When I look back to the glory days of the Royals, geez, they still talk about them.”

Rivalries between communities were fierce. Still are, in some cases. In the heat of the playoffs, the next town might as well have been Moscow, and the opponent, the Red Army.

Ray Brethour lived the same experience, only his idols were the Hamiota Huskies of the 1960s. He still has vivid memories as a boy overwhelmed at the excitement of a jam-packed Hamiota Arena.

“Oh, for a six-year-old kid, in your own community, you wouldn’t believe it,” says Brethour, who now serves as president of Manitoba senior hockey. “The arena was packed. It was noisy. It was the place to be. It was the same in every other community. It was the only show.

“It was like your first Jets game. It sticks in your mind.”

In Pilot Mound, Rod Collins remembers, too.

“The old rink, they’d put 1,200 people in there,” he says of the nights the Pilots played, “and the girls used to come up and down the boards and serve coffee because it was so jammed. To me, that was like the Big Apple when I was a kid, watching the senior team play. That was everyone’s ambition growing up in a small town.”

Alas, the Falcons are no more, and there is no senior team in Hamiota, either. But the Royals and Pilots are still card-carrying members of the Tiger Hills Hockey League.

And the Kenton Cougars, bless them, are still looking for their third win of the season.

***

Pierson

Six-town team

PIERSON — Paige Pettinger, 11, plays on a peewee girls hockey team that is made of up of kids from six neighbouring towns, including one just across the border in Saskatchewan.

That’s right, six.

The team plays home games in all of the communities, including Pierson, where Paige lives. But since most of the players come from Deloraine, about 40 km to the east, that is considered home base and the site of many practices.

There are some 250 residents of Pierson (at least, before the oil boom imploded), which is tucked into the very southwest corner of Manitoba. A generation ago, Pierson had teams in all minor hockey divisions. Now it has one (ages four to six).

The result: teams are now cobbled together from three to six communities within a 60-km radius. They are then forced to travel further afield to play a team made up of players combined from several more neighbouring towns.

“Two hours is nothing to go to a hockey game,” says Matt Pettinger, 32, Paige’s father and coach of the lone Pierson minor team, which includes his son Rohan. “You’ve got to love hockey to want to do it.”

On a Friday night, Pettinger is sitting in the Edward Sports Centre arena with buddy Tim McCannell, whose two young children are playing on the ice with Rohan. The arena is spacious and, by small-town standards, relatively new.

It opened in 1977. It’s empty on many nights.

As Pettinger and McCannell chat, a group of young women who suit up for rec hockey every week take the ice as Cotton-Eyed Joe blares over the loudspeakers. Says Pettinger: “You can come right down here and chances are you can have the whole rink to yourself.”

Meanwhile, just a few kilometres down the road, in Carievale, Sask., Laura Johnson is watching her seven-year-old daughter, Jessie, take the ice. Johnson has two other hockey-playing children: 12-year-old Cassidy and Jimmy, 10. Not one plays in Pierson. Jessie’s team is based in Carievale (about 25 km away), Cassidy’s team is in nearby Melita, and Jimmy plays out of Carnduff, Sask. (40 km away).

A hockey assist

Struggling to keep the rink open? Need a new scoreboard? Some new uniforms? Maybe subsidize registration for players who can’t afford it?

The Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame is currently accepting applications for its inaugural Community Award grant, which is offering $10,000 to community organizations trying to keep hockey affordable.

Or just keep hockey, period.

“We want to improve the grassroots,” said Jordy Douglas, vice-president of the MHHF.

“Hockey is becoming too elitist and expensive. We know we’re not going to solve that problem. But we want to encourage kids who live the game to keep playing the game.

“Communities are dying on the vine out there,” he said. “Can we keep kids involved? We’re just trying to give a little back.”

The MHHF is putting up $5,000, and is hoping to partner each year with a corporate sponsor. The sponsor for this year’s award is Sigfusson Northern Ltd. construction company in Lundar.

“We want to do this every year,” Douglas said. “We want to get as many applications as we can. We’re just trying to make sure everyone knows about this opportunity.”

The deadline for applications is April 30. More information and applications are available on the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame website.

The winner will be announced June 1.

It’s a touch of irony Johnson’s husband is a truck driver who works in a potash mine west of Regina, but she puts on far more miles behind the wheel in the winter months. In the last three months, Johnson can count on one hand how many days she hasn’t spent in a hockey rink.

“We just car pool,” she says.

“Everyone’s in the same situation. We’re all in the same boat. We kind of make it work however we can.

“My kids love it, so it’s definitely a choice we’ve made. You have to really want it out here. It’s a struggle for everyone. It’s a huge expense and a huge time commitment.”

“It will take the whole southwest corner” of the province to field a bantam team (13- to 14-year-olds), McCannell says, which creates the curious dynamic where parents who grew up immersed in bitter hockey rivalries now have to band together just to keep the game alive.

“That’s one good thing,” he concedes. “The kids are all buddies.”

But the bad news is twofold: the increased cost and travel; and the loss of revenue that keeps the arena lights on.

Sure, you can show up at the Edward Sports Centre — and many other rinks in a town of similar size — at the drop of a puck and play. But Pettinger notes: “It’s hard to keep the rinks maintained with nothing coming in. Our hydro bill is $3,000 a month.”

Much of the operating expenses for the Pierson arena come from an annual craft sale, which attracts more than 1,000 people each year. Precious little comes from hockey itself.

As for the dwindling number of players of all ages, McCannell says: “I can see people who are starting up with kids asking, ‘Do we really want that?’”

Peter Woods, executive director of Hockey Manitoba, expresses similar concerns.

“It’s tougher,” Woods says. “Families are not as big as they were 20 or 30 years ago. So, yeah, it’s become a little bit more difficult and a little bit more expensive. Eventually, they’ll end up losing teams and players will find other interests because of the hardship that’s involved in travelling.

“The more teams you have in a designated area, the more competition you have. That could be lost. You have to go further for that competition now. It’s a concern for us all the time.”

But, frankly, Hockey Canada can’t control rural population any more than it can control the weather.

***

Minto

‘Why not just form our own team?’

One alternative is the emergence of recreational hockey. In Ninga, a hamlet about 70 km south of Brandon, local volunteers have organized five teams for players between the ages of four and 18 that play games and tournaments outside the Hockey Manitoba umbrella.

Roughly 60 children are involved, a total that far exceeds the community’s population.

And just last year, a rec team for 14- to 18-year-olds was formed in Minto, a village about a 30-minute drive away.

“We were sending our kids to Ninga, so we thought, ‘Why not just form our own team?’” Sonia Stewart says.

Such grassroots teams are sprouting all over the Prairies, allowing children to play the game without the excessive cost and travel.

“They way things are changing, it’s going to keep dropping (rural hockey participation),” Johnson says. “And it’s too much now about where the kids can go in their hockey career instead of just playing hockey.”

Yet, in the same breath, the hockey mom/long distance driver said her children will persevere.

“None of my kids would be quitting any time soon,” she says. “They love it.”

***

Alonsa

‘They don’t even mind playing on lousy ice’

Night has fallen in Alonsa, and the blowing snow of an impending blizzard is just beginning to skirt this community just west of Lake Manitoba.

All is quiet. Until you set foot in the town arena.

There, all is loud. All is happy. All is here for a party.

Welcome to the annual Alonsa recreational hockey tournament, which, every February, is the biggest thing to hit town. (Except this summer, when Juno Award-winning band Doc Walker will be playing a concert because, as Shawn Gurke notes, “They have fond memories of playing here before they made it big.”)

Gurke is a member of Club 2000, a group designed to oversee fundraising efforts for the community’s hall, rink, museum and seniors centre.

“Basically,” he says, “we absorb expenses to keep things going. It’s all one pool.”

The major source of revenue is a weekly bingo game. But on this February night, the proceeds from the tournament (about $1,000, they hope) will be used to purchase a new arena score clock, as only every other light bulb is currently working.

“This is the big hockey tournament,” Gurke says. “It pretty much brings everybody back from college or wherever they’re working.”

Indeed, the arena is jammed. The beer is flowing. There’s even a game being played on the natural ice.

“It’s great,” says David Senkowski, who has suited up for the last few years with Hailey’s Comets, a team largely made up of his daughter’s friends from university.

“It gets a lot of people out here. We wouldn’t have a tournament like this if we didn’t have that extended family. And they don’t even mind playing on lousy ice because the money that’s raised goes to the community.”

“It’s pretty idyllic in a lot of ways,” Gurke adds. “You hope you do well and throw the money in the kitchen and keep it all running. I think it’s beautiful. Because it’s a genuine thing from all the people in the community.”

But the reality is never so sentimental. The area around Alonsa has been devastated by repeated flooding. Gurke, a conservation officer, says the district’s population has fallen below 1,000 — down from around 2,300 in 1981, according to Statistics Canada.

“It’s been hard for us,” he says.

Like most communities, it can’t afford replacement insurance on its hockey arena anymore. So you keep volunteering, you keep upgrading where you can, and you pray for no natural disasters.

It’s no different in Kenton or Pierson or Manitou.

***

Baldur

‘It’s a community thing’

In Baldur, there is no artificial ice. The kitchen is operated by a rotating staff of 100 volunteers on rotating shifts, where they serve up a critically acclaimed burger for $3.50.

Like in most other towns of less than 1,000, Baldur has no senior team (R.I.P., Barons). The kids find teams to play on where they can.

“We just don’t have the numbers,” says Travis Johnson, owner of the local newspaper, the Baldur Gazette.

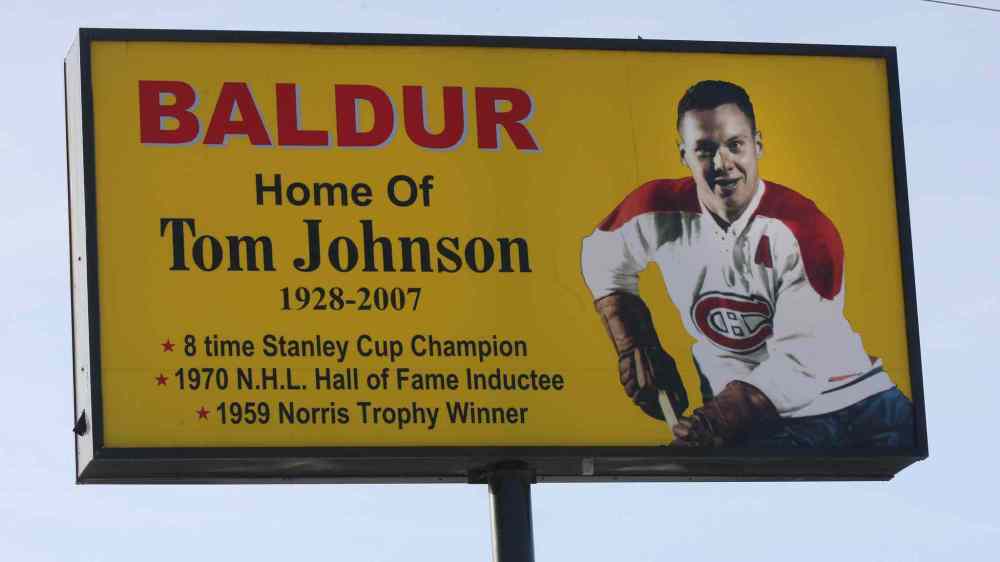

Still, Baldur is the home of Hockey Hall of Famer Tom Johnson, and, if you don’t believe it, just check the giant sign towering over the main drag.

And it still keeps its arena doors open, not just for hockey but auction sales, socials, fall suppers, graduation celebrations and wedding dances.

In fact, the biggest town celebration each year is the Summer Solstice Days. It’s as much a community reunion as anything, when guys such as Darcy Dearsley will sit during the social in the arena and talk about games gone by, or when, as kids, they’d be chased off the rink, only to walk on their skates to the nearest slough to continue playing.

“Lots of fun years, I’ll tell ya,” Dearsley says. “There’s lots more to do nowadays, but we still spend a lot of time here. And, during solstice, we’ll bring up a lot of stories to keep the old days alive.”

But let’s face it, they’re trying their damndest — flooding the ice, baking the pies, driving the kids, selling the social tickets — to keep the new days alive, too.

***

Back in Foxwarren — did we mention it was also home to NHL players Ron Low and Pat Falloon? — Bev Wotton has been asked what makes her arena so special, even after all these years.

The kids are on the ice. The kitchen is humming. The parents and family members are lined up against the Plexiglas. A woman is selling raffle tickets at the door.

One of the oldest hockey arenas in Manitoba never looked so young.

“People are socializing and getting together,” Wotton says. “And I’m seeing people come to watch their grandkids who used to come and watch their kids. It’s a community thing. That’s what keeps it going.”

There are no tears in her eyes.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.