Shadow on the game

Former CFL players tackle their greatest challenge as the full effects of sport concussions brought to light

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/12/2015 (3657 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

He remembers the four Grey Cup wins. He remembers his Hall of Fame teammates. He even remembers single plays he authored that changed the history of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers franchise and which fans still talk about more than 50 years later.

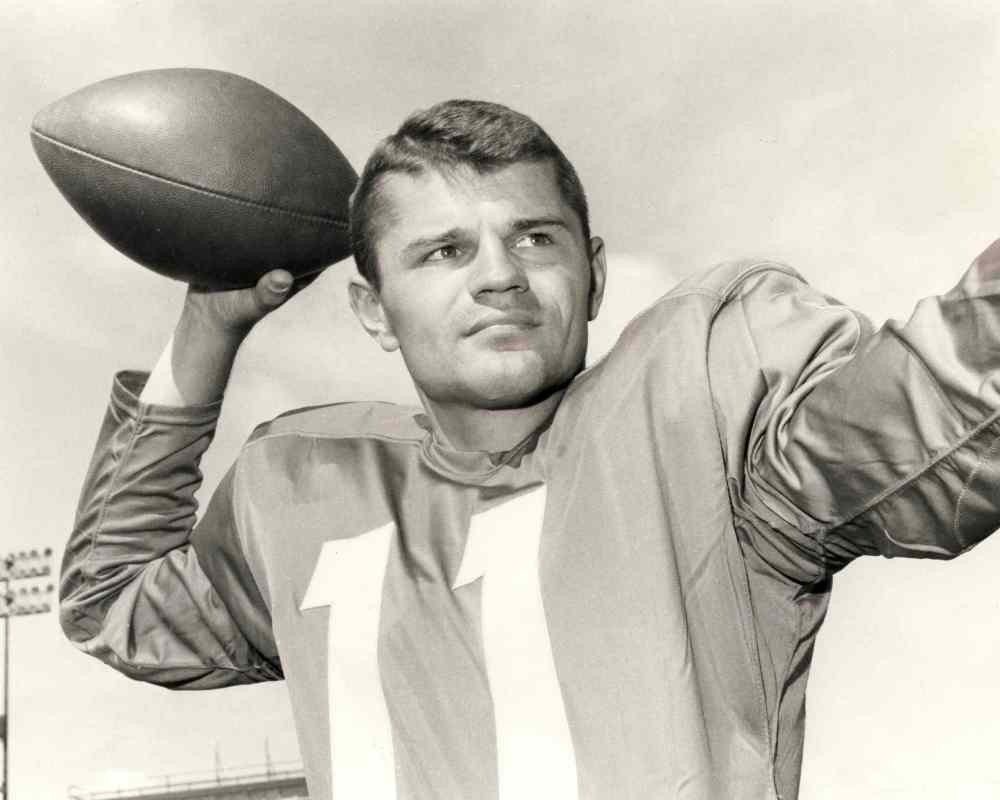

But what Canadian Football Hall of Fame quarterback Ken Ploen no longer remembers is what he did yesterday. The greatest Bombers player who ever lived has been diagnosed — like an alarming number of his aging CFL teammates — with dementia.

“He’s still in great health otherwise. We just had our checkups and the doctors say he has the heart of a 16-year-old,” says Janet Ploen, his wife of 55 years.

“He’s still able to get out and he’s still able to do things. It’s just that he doesn’t remember the experience the next day.”

Case in point: Ploen, 80, got together last weekend with football legend and former Bombers head coach Bud Grant, 88, during a Grey Cup event in Winnipeg. Ploen remembered Grant vividly, Janet says, and the two men spent time together reminiscing about their CFL glory days in the 1950s and ’60s.

The following day, Ploen had mostly forgotten the meeting.

Fifty years ago? No problem. Yesterday? Not so much. It is the insidious nature of dementia, a catch-all diagnosis for a wide range of brain diseases, including Alzheimer’s, that slowly rob sufferers of cognitive abilities and memory.

It’s a tender mercy Ploen thus far retains his long-term memories and can recall the greatest moments of an exceptional life. Who needs to remember yesterday, after all, when your yesteryear is so rich and so full?

“Ken likes to tell me,” says Janet, “that he remembers what he wants to remember.”

Among those memories Ploen has retained are some of the savage hits to the head he took during a 10-year career with the Blue Bombers from 1957 to 1967.

“They didn’t talk about concussions in those days; they said you got your bell rung,” says Janet. “And Ken says he can remember a few times when he got his bell rung.”

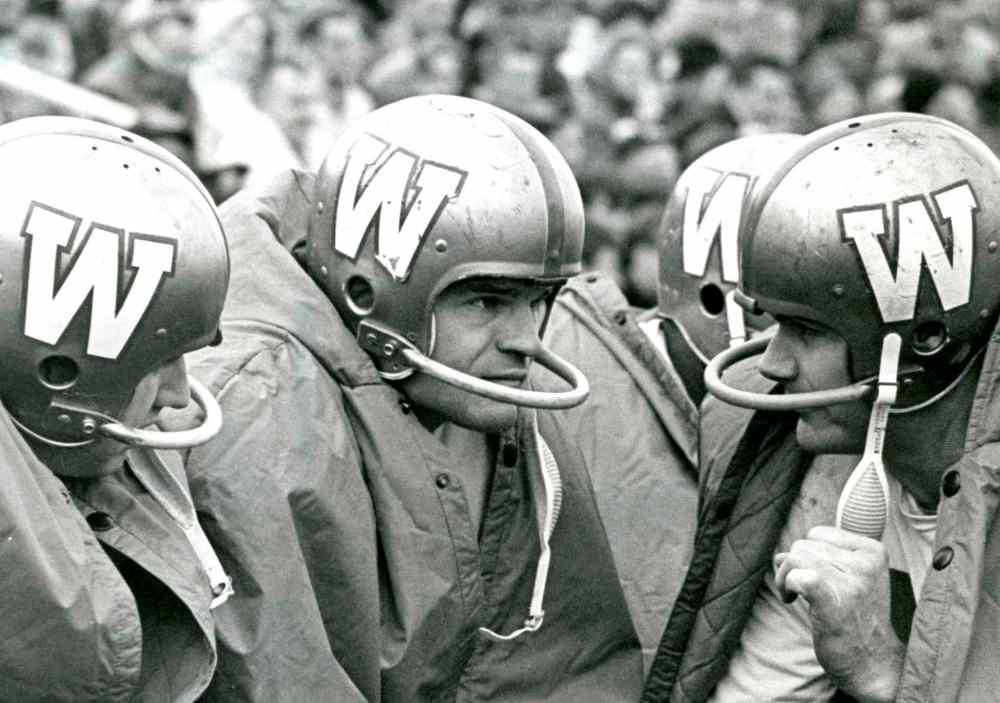

Nick Miller says everyone got their bell rung in those days and the Bombers training staff had a rudimentary way of determining whether you were ready to go back into the game.

“They asked you how many fingers they were holding up, what day it was, what the score was,” recalls Miller, a Bombers halfback from 1953-64 and a member of the club’s Hall of Fame.

“They took sprained ankles more seriously in those days than concussions. Because a sprained ankle could cause you to miss a game or two, but a concussion just meant you missed a play or two.”

It’s the opposite these days. Medical research has shown one of the worst things you can do after suffering a concussion is not allow what is basically a bruise on your brain adequate time to heal.

And so these days, the NFL and CFL have rigid concussion protocols every player has to undergo — and pass — before they are allowed back on the field. It’s serious medical condition taken very seriously — and it’s why Calgary Stampeders running back Jon Cornish announced earlier this week he’s retiring at 31, after taking one hit to the head too many.

No one knew any better in the 1960s and, besides, a generation of men who came of age during the Second World War weren’t about to whine about a little headache.

Instead, they made light of concussions. Still do, in fact.

Miller recalls the time he got knocked unconscious while tackling a Stampeders running back late in the first half of an afternoon game.

“I had him dead to rights and he tried to jump over me. And his knee hit me right in the head and knocked me out. And then he fell down and he was knocked out, too. It was,” Miller says with a laugh, “like a Road Runner cartoon.”

And just like Wile E. Coyote, Miller got right back up after that 1,000-foot plunge off a desert cliff.

“I was back in the game,” he recalls, “by the third quarter.”

It was all very cavalier, and it’s all catching up to them now, says Miller.

A longtime board member of the Bombers alumni association, Miller says an alarming number of his former teammates have been diagnosed in recent years with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

Old guys from any walk of life get dementia, but Miller — reciting a long list of former CFL players battling the disease — says the sheer number of cases seems disproportionate.

“It seems like everyone is having trouble with this,” he says. “It seems like an epidemic.”

t seems that way, of course, because there is an increasingly compelling body of research that says it is.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock — or in the office of the commissioner of the NFL — you’ve probably heard all the stories and all the studies in recent years that increasingly suggest football is killing football players.

In some cases, players are dying prematurely — Mike Webster (50) of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Junior Seau (43) of the San Diego Chargers and Dave Duerson (50) of the Chicago Bears all died way before their time.

In other cases — Pro Football Hall of Famer Frank Gifford, 84, most recently — they are withering away in old age.

But what those men had in common is a condition researchers call chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Here’s how researchers at Boston University, pioneers in the field, describe it on their website:

“Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in athletes (and others) with a history of repetitive brain trauma, including symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic sub-concussive hits to the head. CTE has been known to affect boxers since the 1920s. However, recent reports have been published of neuropathologically confirmed CTE in retired professional football players and other athletes who have a history of repetitive brain trauma. This trauma triggers progressive degeneration of the brain tissue, including the buildup of an abnormal protein called tau. These changes in the brain can begin months, years, or even decades after the last brain trauma or end of active athletic involvement. The brain degeneration is associated with memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse-control problems, aggression, depression, and, eventually, progressive dementia.”

Boston researchers announced this year they found CTE present in 87 of the 91 brains of former NFL players they’ve examined. Last spring, a federal judge approved a settlement in a class-action lawsuit against the NFL that resulted in former players affected by CTE receiving up to US$5 million each in compensation.

A similar lawsuit against the CFL is still before the courts. A Canadian version of the study being done in Boston is underway in Toronto.

And that sound you hear? That’s a ticking time bomb.

Henry Janzen doesn’t like using the term dementia.

“I prefer,” he says, “to tell people I have short-term memory problems.

“People hear I have dementia and they get alarmed, ‘What’s wrong with Henry!’ So I just tell them I’m having memory problems.”

A punt returner for the Bombers from 1959-65, Janzen followed up his Hall of Fame career by getting a doctorate in education and having a distinguished career in academia at the University of Manitoba — athletic director, head coach of back-to-back Vanier Cup champions (1969-70) and dean of the university’s faculty of physical education from 1978-97.

Like Ploen, Janzen has nothing but fond — and vivid memories — of an exceptional life lived. But like Ploen, his day-to-day life the past couple years is blurry, like watching clothes spin in a dryer.

Does he blame football? A little bit. But not in the way often seen in an era in which it sometimes seems everyone is a victim and everyone wants a settlement because of it.

“I loved my experience playing football,” says Janzen, 75. “And everything I have in my life started with football. But, unfortunately, I’m now having memory problems… There’s no question that age is a big factor in memory loss. But I also took a lot of hits to the head playing football and it makes me wonder if that’s not a part of this, too.”

A lot of people are wondering the same thing. And researchers at Toronto Western Hospital are hoping with the help of former CFLers such as Miller and Janzen, they will eventually have some answers.

Researchers have flown Miller and Janzen — along with dozens of other former Blue Bombers and CFL alumni — to Toronto in the past year or so to take part in the Canadian Sports Concussion Project, an exhaustive study on the effects of sport concussions on the brain.

The former CFLers are subjected to testing over the course of two days ranging from MRIs to memory and reaction tests to probing discussions on mental health, including questions on depression and suicide.

At the end of the tests, they’re asked to sign a form that, upon death, donates their brain for further study.

It’s a critical final step as it’s only by cutting open a former player’s brain that researchers can determine for certain if there are the lesions and proteins present that prove those repetitive head injuries led to those cognitive difficulties later in life.

Dr. Carmela Tartaglia, a neurologist and the clinical and bio-marker lead on the project, says 61 former CFLers have already enrolled. She was in Winnipeg during Grey Cup week hoping to recruit more to take part.

“The study calls for 100 people, but we’re hoping to get even more,” Tartaglia says during a phone interview Friday from Toronto. “One-hundred people compared to all the people who played isn’t a large number. But we’re hoping it’s enough to begin to answer some questions.”

Tartaglia says none of the CFLers taking part in the study have died yet, but researchers in Toronto have obtained the brains of 20 deceased former pro athletes who’d suffered multiple concussions in their careers — including former NHLers — and found evidence of CTE in 10 of those samples.

Miller has been encouraging his former teammates to make the trip to Toronto: both to get some answers for themselves, but also to help researchers get to the bottom of a problem some think could ultimately threaten the survival of pro football.

“This is a very important study. I’d hate to see this kill the game,” says Miller. “And I’d hate to see the CFL become the CFFL — the Canadian Flag Football League. I’m encouraging all the players to become involved.

“I’ve donated my brain, so I’m telling those guys out there, ‘They accept small donations.’ ”

Nothing, ever, scared Chris Walby in a 16-year Hall of Fame career as an offensive lineman for the Blue Bombers.

He took on the toughest defensive linemen in the history of the Canadian game. He lost a few battles, he won more — but more than anything, he never backed down out of fear.

Until now.

Walby, 59, is brutally honest when he explains why he hasn’t joined Miller and Janzen and the others in taking part in the Toronto concussion study.

“My wife really wants me to do it,” says Walby. “She says I forget a lot of stuff.

“And there’s a part of me that really wonders, too. Sixteen years of banging my head, what effect did that have on me in the long term? But there’s also a part of me that’s very nervous about what they might find. My mother had Alzheimer’s and dementia, too, unfortunately. So I wonder if it’s not a hereditary thing for me, too, and the football is going to speed the whole thing up.

“There’s a real fear factor here for me — what you don’t know and what you don’t want to uncover.”

Former Bombers defensive lineman Doug Brown, on the other hand, is almost obsessive in his quest to learn everything he can about CTE. Brown’s taken part in an American study, he is a regular visitor to websites and blogs that track the problem and he’s written extensively about the issue in his weekly column for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Speaking of that column, Brown says it’s one of the things that worries him as he ponders life after a 15-year pro football career that ended in 2011.

“I’ve re-read some of my old columns and I don’t think I write as well as I used to,” he says. “I’m not sure if it’s just not as sharp or not as funny, but I just don’t write the same way as I used to.”

When he was examined as part of the U.S. study, Brown, 41, says a doctor told him there were some “spots” on his brain that turned up in a MRI the physician described as “interesting.”

Brown says he was also told no one will know for sure what effect — if any — football had on his brain until he’s dead.

It raises interesting questions: if you knew then what you now know about CTE, would you have managed your career differently? Retired earlier? Played differently? Not played at all?

“I know I would have wanted to have been paid more,” Brown says with a laugh. “But you’ll have to call me again in 20 years before I’d be able to definitely tell you if it was worth it — and if I’d still do it all over again.”

A lot more will be heard about concussions and CTE as the television advertisements and trailers ramp up for the release later this month of Concussion, starring Will Smith.

The film, based on a 2009 article in GQ, tells the real-life story of forensic neuropathologist Bennet Omalu, who is widely credited with linking CTE to pro football players and who had to fight vicious attempts by the NFL to discredit him and suppress his research.

There’s a scene in the film in which Smith’s character is warned about the wisdom of taking on the NFL: “You’re going to war with a corporation that owns a day of the week.”

Some are wondering if the movie — with a big-name star, Hollywood production values and a worldwide theatrical release — will do for CTE sufferers what the 1993 Tom Hanks film, Philadelphia, did for people with HIV and AIDS and put a human face on all those faceless news stories and, by humanizing the problem, lead to grassroots calls for action.

Maybe, but whatever comes of the movie, it will come too late for the likes of Janzen and Ploen.

“My memory problems,” says Janzen, “are only going to get worse, not better.”

And Ploen? He speaks in short, clipped answers these days.

Ask him a question and he will answer it succinctly, but without elaboration. Friends who have known him for decades say the greatest Bombers player of them all now prefers to be more a spectator than a participant in social situations.

How’s he feeling?

“I’m doing fine.”

Did he enjoy the Grey Cup?

“I lived it up a little bit.”

How’s his memory?

“I don’t think it’s too serious.”

Janet Ploen says dementia also runs in the Ploen family — his father, sister and brother all suffered from it or are suffering with it. So who knows, maybe Ken Ploen the accountant would have ended up with this same problem?

And what does Ploen think?

“I’m sure,” he says, “football had an effect.”

The last word goes to Miller, seen on the dance floor at the Grey Cup Dinner Gala last Saturday as rock legend Randy Bachman hammered out the iconic guitar line from the Guess Who classic, American Woman.

Miller looks great and is mentally sharper at 84 than many in their mid-40s.

And so, with such an alarming number of his former Bombers teammates ailing, how does he feel?

“I feel guilty,” Miller says, “because I don’t have any health problems at all.”

Twitter: @PaulWiecek

Paul Wiecek

Reporter (retired)

Paul Wiecek was born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End and delivered the Free Press -- 53 papers, Machray Avenue, between Main and Salter Streets -- long before he was first hired as a Free Press reporter in 1989.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.