Dancing with death

Physicians fear toll will rise with number of Winnipeggers addicted to fentanyl

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/11/2015 (3663 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Three years ago, Nicki walked out of a Main Street methadone clinic unaware a predator lurking outside was poised to pounce.

The man approached the petite 20-year-old brunette, who was trying to kick OxyContin and Percocet addictions, and tempted her with a new drug called fentanyl, an opiate more powerful than heroin.

Nicki declined.

But the predator was smooth. The two got to talking and the young woman, who had started experimenting with booze and pot at age 11 or 12 and graduated to cocaine a few years later, left the man her phone number.

That evening, he called and invited her out for drinks. He introduced her to his boss, who became her dealer, a wealthy, 40-something man she still calls “my guy.” That night was the first time Nicki used fentanyl.

At first she just snorted it. About two years ago, she started injecting it.

“I was so depressed. It made me feel good,” says Nicki, who asks that her real name not be used. “It made me come alive. But at the same time, I’d pass out for hours.”

Her dealer befriended her and she met him regularly. He kept her supplied with the powerful drug free of charge, she said, asking for nothing in return.

But soon many of her friends were hooked. Nicki graduated from sniffing lines of powder to injecting the drug. Twice she “flatlined” after taking the drug, which can slow a person’s breathing to the point where they fall into a coma and die. She was saved by paramedics both times.

She knows five people — including a former boyfriend — who have died from fentanyl overdoses.

She recalls her panic after witnessing friends who were passed out and unable to breathe.

“My heart was racing. I was freaking out, screaming,” she says in a recent interview.

On several occasions, paramedics arrived just in time. Other times it was too late for them to do anything.

The day she met her former boyfriend, the one who is now dead, her “buddy” paid her taxi ride to a party. She brought fentanyl. Her boyfriend wound up in a coma for nearly a week after taking the drug, while his best friend “died on the spot.”

Fentanyl is so strong that a line of powder a couple of centimetres long can knock a person out, Nicki says.

“It really is that powerful.”

Winnipeggers were alerted this summer to the dangers of fentanyl, when police linked it to two overdoses, one of them fatal.

But it’s been a concern of doctors who work with opioid addicts for some time.

Dr. Murray Hoy, who operates a methadone treatment program with his physician brother Gerald, says the problem is more serious than the public thinks.

“It’s huge,” he says. “The number of kids dying of fentanyl right now is incredible.”

There are no official Manitoba statistics available on fentanyl-related deaths this year, but the Hoys say they’re aware of about a dozen since May.

The Winnipeg Fire and Paramedic Service reports that in the first 10 months of this year, paramedics and firefighters responded to 96 calls involving fentanyl in which the opioid poisoning antidote naloxone (known by the trade name Narcan) was administered.

In an analysis of first-responder reports at the request of the Free Press, the WFPS says that 41 of those calls involved immediate life-saving intervention because patients had stopped breathing or were in cardiac arrest.

Because these latter patients tended to be younger — the average age was 33 — they were more likely to survive, says Dr. Rob Grierson, the WFPS’s medical director, who also works half-time as an emergency room doctor at Health Sciences Centre.

He says it would take more time to determine how many of the patients died. That would involve cross-referencing incident numbers between the fire paramedic service and the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

But he says the number of life-threatening cases is troubling. No other drug produces so many close calls, he says.

“That’s the part that is most concerning. And I think that’s what has everybody in North America alarmed about fentanyl. By the time you get into trouble (overdosing), you’re so far into trouble that you may not be able to get out,” Grierson says.

Murray and Gerald Hoy, who run the OATS (Opiate Addiction Treatment Services) methadone program at Main Street and Selkirk Avenue, say half of the 20 to 30 new patients they accept into their program each month are fentanyl users.

Some arrive at their door looking for help after attending a funeral of a friend.

“About three months ago, there was a party where six people overdosed from fentanyl. Two of them died, four of them recovered (in emergency),” Gerald Hoy says.

Other clinics that specialize in treating opioid addicts are also noting a surge in fentanyl users.

“It’s becoming really big,” says Nicole Gagnon, who works at Manitoba Addiction Treatment Centres (MBATC) on Selkirk Avenue at Andrews Street.

“I’d say a good 90 per cent of patients who walk in the door have a fentanyl issue,” she says.

At the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, which operates the Methadone Intervention and Needle Exchange (MINE), medical director Dr. Ginette Poulin says while oxycodone remains the most popular opioid amongst addicts, fentanyl use is on the rise.

“I would say there’s a good portion that would have tried it, another portion who will use it when it’s available,” she says.

She believes, however, that “very few” people still view it as their drug of choice.

But Poulin says it’s a dangerous drug because it’s so powerful and fast acting and available in forms in which it’s difficult to discern the dosage.

“The fact that you’re even taking it is a risk. Flip a coin, right? Death or not death,” she says.

“My heart rate goes up every time I hear one of my patients (is on it).”

Grierson says he has seen patients come into hospital in cardiac arrest with pieces of fentanyl patch in their mouth.

Fentanyl patches are prescribed to relieve pain for cancer patients and those with chronic diseases. A patch can hold three days worth of medication. When people use it incorrectly, they’re getting massive doses of the drug, Grierson says.

“It is very fast acting and in high doses it can completely arrest your respiratory drive. You will stop breathing. Once you stop breathing it doesn’t take long for that to be followed by a cardiac arrest,” he says.

Fentanyl has risen in popularity recently as OxyContin (generic name oxycodone) supplies have grown more scarce. Fewer physicians are prescribing the drug and new tamper-resistant forms such as OxyNeo have emerged.

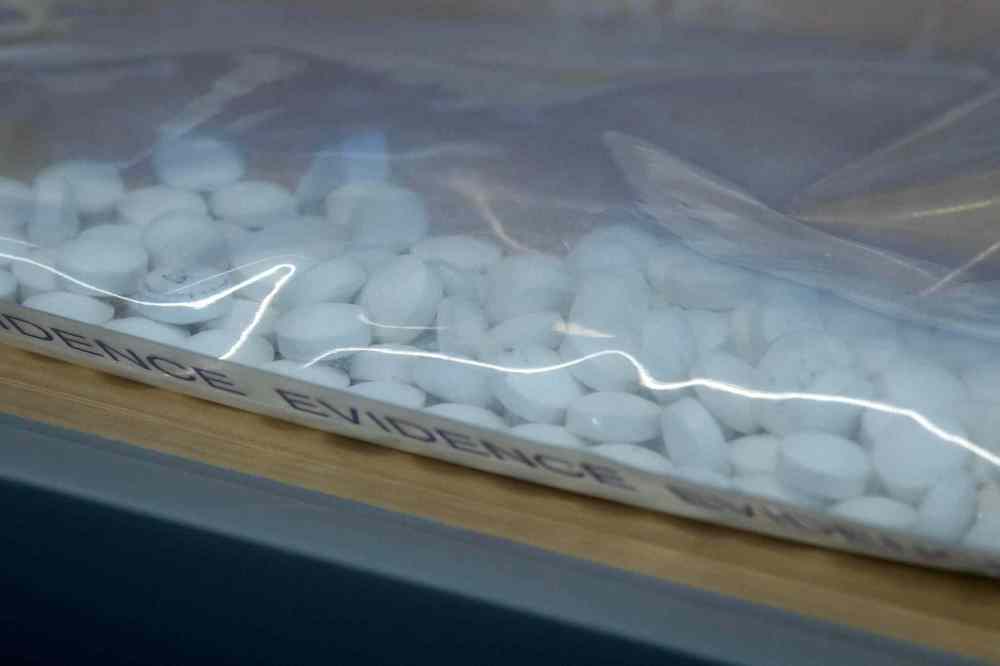

Illicit drug dealers are producing pills containing fentanyl and passing them off as OxyContin.

They’re also mixing fentanyl powder with cocaine — and even occasionally with marijuana — to hook their clients, a prospect the Hoy brothers find frightening.

“If I’m a drug dealer and I want you to take my cocaine vs. Bob’s cocaine, I’m going to put something a little extra in there to get you truly hooked on my product, which is the opiate,” Murray Hoy says.

“From a business standpoint, it’s brilliant, but it’s pure evil,” his brother Gerald adds.

Because the drug is so expensive — addicts can pay anywhere from $200 to $400 a day to feed their habit — most of their fentanyl-using patients are middle class or upper-middle class, they say. They include addicts in Lindenwoods, River Heights, Tuxedo, St. Vital, Steinbach and Pritchard Farm in East St. Paul among other communities.

The physician brothers operate a second clinic on Pembina Highway to serve their many south Winnipeg patients.

“It’s younger and more well-to-do,” says Murray Hoy of those hooked on fentanyl. “They’re the only ones who can afford it, really.”

The average age of their clients is about 25. Gerald Hoy says one of his newest patients is only 16.

“No other clinics in the province would treat this kid because of his age. And because it was (an) emergent (case) I took this kid on or else he’s going to die of fentanyl,” he says.

The brothers say the government appears to be unaware of the seriousness of the problem.

They are upset the provincial Health Department won’t cover the cost of a basic urine test-strip, or dipstick test, for fentanyl. They are now paying for that out of their own pockets. The cost is about $1 per test, not counting labour costs. They also say there are no labs in the province that provide a confirmation test for the drug.

“They’ll confirm all the other stuff except fentanyl, because the government is refusing to pay for that test,” Murray Hoy says.

* * *

Local authorities estimated there had been seven fentanyl-related deaths in Manitoba in the first six months of this year — the same number as the official total in all of 2014.

Despite this apparent spike, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority reported that its hospitals and addictions programs had not seen any huge increases in fentanyl use.

Out West, the media have described the growing death toll in suburban Calgary and other Alberta communities as a “crisis.”

The Calgary Herald reported in August that fentanyl had been responsible for more deaths in the southern Alberta city this year than homicides and traffic collisions combined.

Alberta’s chief medical examiner blames fentanyl for 145 deaths in the first six months of this year and has promised an update in December. Of those deaths, 43 occurred in Calgary, 32 in Edmonton, 14 in Grande Prairie, 13 in Fort McMurray and 10 in Red Deer.

The number of fentanyl-related deaths has exploded in Alberta — from six in 2011 to 66 in 2013 and 120 in 2014, according to the province’s health department.

In Saskatchewan, the chief coroner said earlier this month there were 25 fentanyl-related deaths across the province between January 2013 and August 2015, according to another press report.

However, in Manitoba, the latest official figures are a year old.

Mark O’Rourke, director of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Manitoba, says he has no 2015 statistics as yet on fentanyl-related deaths.

O’Rourke says it takes about three months to get final autopsy reports, so “it’s a little early right now” to provide information for this year.

When asked about a steep rise in the death toll this year, he called such reports “anecdotal.”

“We’ll have to look at that. I can’t say that we’ve made that association yet,” he says.

O’Rourke says the information takes time to process. “It’s only November. We still have a lot of cases to go through.”

Manitoba Health Minister Sharon Blady says she’s putting together a committee to develop a strategy to combat the use of fentanyl.

“As a mom, I find it very frightening that this is out there,” she says.

Blady says the province “wants to be proactive” in dealing with the dangerous drug.

“While it has cropped up here in Manitoba, it’s become a crisis in other provinces. So we’re trying to stay ahead of that,” she says. “We’re trying to prevent the crisis that’s occurred elsewhere.”

Blady says her advisory group will include representatives from the regional health authorities, the Justice Department and those with “on the ground” experience.

She says she’ll have more to say on the subject in a few weeks. That will include improvements in patient testing and possibly issuing kits containing the opioid antidote naloxone for at-risk users.

Equipping addicts with injectable naloxone or a fast-acting nasal spray is already occurring in other jurisdictions.

By September, Alberta had distributed 350 naloxone kits to opioid users. At least 30 of them have been used to save lives, Alberta Health reports on its website.

Meanwhile, in Saskatchewan, naloxone kits are being distributed as part of a pilot project in Saskatoon.

Blady says Manitoba is looking at following suit. “That is something that’s been under consideration, and it is being discussed. We’re trying to see where it fits in (in the battle against fentanyl).”

Dr. Poulin, of the addictions foundation, says supplying kits “certainly warrants discussion,” but she warns that it is not a panacea.

It won’t, for example, help an addict who is alone using the drug — someone needs to administer it and call for help, she says. Given the high doses of fentanyl that are often ingested, repeat doses of naloxone may also be required so it’s important that paramedics are called.

And if fentanyl is mixed with cocaine and other drugs, naloxone — which only counteracts opioids — won’t necessarily be effective, Poulin says.

Nicki, now nearly 24 years old and off fentanyl for a year, says she doesn’t believe there will ever be a day in which she doesn’t feel the harmful effects of the drug.

“Even when you quit fentanyl you still suffer from it every day,” she says.

“I dream about it all the time. I have constant dreams, and I wake up sick. I have withdrawal from those dreams. It’s not fun.”

She’s now in the process of weaning herself off of methadone — a drug used as a substitute in the treatment of opioid addiction.

Nicki says she was determined to quit using fentanyl after she became pregnant with her son, now three months old.

When the boy was born, he spent his first several weeks in hospital to cope with methadone withdrawal.

If it weren’t for her son, she would likely be dead, she says.

She avoids her old friends because she knows if she socialized with them, she’d suffer a relapse. Her life, these days, revolves around her son and her extended family.

She has not been able to work since using fentanyl. She takes Valium to cope with social anxiety. She says she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder after witnessing deaths and near-deaths due to the drug.

Her advice for someone thinking about experimenting with fentanyl?

“It’s way stronger than you think it is. It will kill you. Just don’t do it. It’s not worth losing your life.”

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

Treating opioids addiction full time

About three dozen physicians in Manitoba are authorized to prescribe methadone or suboxone, drugs used to help wean addicts from opioids like fentanyl and OxyContin.

But few doctors have made opioid treatment a full-time practice.

However, two brothers, Dr. Murray Hoy and Dr. Gerald Hoy, who operate the OATS (Opiate Addiction Treatment Services) on Main Street at Selkirk Avenue, have always been unconventional.

The pair excelled in sports at Kelvin High School in the 1980s, but dropped out of school before graduating.

“We were in high school for athletics. That was it,” says Murray, who participated in track and field, while Gerald played football.

They later completed high school as adults and trained as nurses. They spent years practising in northern nursing stations before entering medical school.

“I never wanted to practise addictions medicine. I always thought it was a scummy line of work,” says Gerald, who was trained as a family physician. “We still get no respect from our colleagues for practising in this field.”

Says brother Murray: “Nobody wants to do this work. That’s the other part of the problem. Nobody wants to treat our clients.”

Murray, 49, started working at another methadone program clinic not long after graduating from medical school in 2001 and then later joined brother Gerald, 48, to form their own practice.

Both have found treating addicts to be very satisfying work. They’ve seen patients who could have easily ended up dead return to high school and go on to college or university and join the workforce.

“I describe family medicine as helping people die slowly,” says Gerald. “Here we save lives every week, if not daily.”

Their clinic specializes in stabilizing addicts on methadone so that they can function and get to the point where they can attend counselling and become productive citizens.

Addicts who try to quit using an opioid will find themselves in full-blown physical withdrawal: sweating, nausea, diarrhea, aches and pains. They’re edgy, irritable and short-tempered, the doctors say. Methadone helps them cope.

Some patients are able to then wean themselves from methadone after a relatively short time, while others remain on the drug for many years.

“There are clients that will be on it long-term, 10 to 20 years or for life, because that’s what they prefer to do instead of going back to heroin, morphine and that kind of stuff,” Murray Hoy says.

The two doctors don’t have a waiting list per se, holding patient intake days once every four weeks at their North End location. They also operate a second clinic on Pembina Highway for their many south Winnipeg clients.

Currently, they have a combined 470 patients — more than any other clinic in Winnipeg.

The Hoys do some patient counselling but recognize it’s not their forte. They refer patients to psychiatrists and psychologists, although none practises with them on site.

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

Mother, daughter struggle with drug

Bre, 41, likens fentanyl to “that little devil on your shoulder.”

It’s something that “makes everything feel better, so you use it to get away from reality,” she says.

She and her 22-year-old daughter are both undergoing methadone treatment to wean themselves off fentanyl at the Opiate Addiction Treatment Services (OATS) program on Main Street.

Bre (not her real name) says she quit drinking alcohol in 2009. Around the same time, she started taking Tylenol 3s, which contain an opioid, while visiting a friend who also used the drug recreationally.

She later graduated to Percocet (which combines acetaminophen and oxycodone) and then to OxyContin (a synthetic drug similar to morphine).

Bre had been undergoing methadone treatment for nearly two years and says she was doing well when her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend introduced her to fentanyl.

“Once in a while I would get down — you’d feel a little bit antsy or something — maybe you were going through something really bad … alone or overwhelmed,” Bre says.

That’s when the “little devil” would speak to her.

“You crave it but you can’t always find it. And it’s not cheap, right?”

Dealers charge $15 to $20 a “point” — a 10th of a gram, she says. Since the drug is fast-acting and its effects short-lived, a gram can disappear in a flash, she says.

“It’s a really expensive drug and it doesn’t last that long. So you’re constantly doing it,” she says.

Bre is employed but wouldn’t reveal her occupation. In a recent telephone interview, she says she’s been back on methadone for the past few months.

She hopes to shake her reliance on opioids but knows there are no guarantees.

“That is your goal, right? I was doing really good on the program before… It’s powerful, right?” she says of fentanyl.

“It’s the opiate that’s really a hard one to kick so I would like to say yes. But at the same time if it was there right now, would I do some? Maybe. I’m not sure.”

Bre notes her teenage daughter’s addiction is more stubborn.

“I think she’s struggling with it. She’s struggling with it for sure.”

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, November 28, 2015 8:36 AM CST: adds sidebar