Diamond in the rough

The future of the downtown Bay

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/03/2013 (4755 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

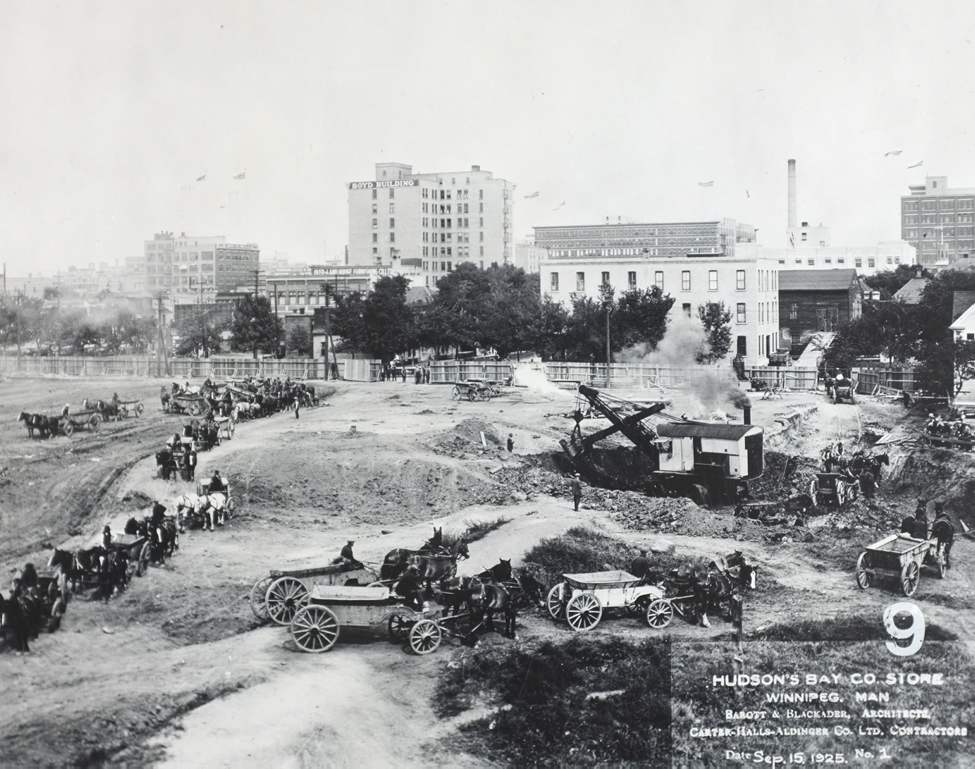

You get a sense things were pretty frantic at the downtown Bay a month before it opened in 1926.

Crazy-busy might be best way to describe it.

There were 914 people working on the new, six-storey department store during the week of Oct. 20, according to the weekly construction report prepared at the time for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Painters, steamfitters, plumbers, plasterers and carpenters rushed to have the building ready for opening day. (See a slideshow of building construction below.) Thrown into the mix were 40 people getting store fixtures prepped and 31 electricians making sure the building’s elevators and escalators were operational.

“Passenger Elevators — four of the cars are running and fifth and sixth wiring nearly complete,” the report says in a terse, hurried way. “Elevator equipment — working on No. 1 & 2 and will be finished about Nov. 1st so that the cars can operate; delivery elevators — both cars cabled and both elevators will be ready by Oct. 30th to operate, providing hatchway is cleared of all obstruction.”

Today, 87 years later, those elevators are, for the most part, mothballed. The sixth-floor Paddlewheel Restaurant closed for good a month ago. The lights are dark on the fifth floor, once the busiest in the building if you wanted to buy a toy, book or LP during the Christmas rush. The Bay now only operates on three floors. Zellers, located in the basement, is closing March 14.

There’s no need for the bank of elevators now because there’s nowhere to go.

What few shoppers there are, the escalators can handle.

One has to wonder whether those elevators will ever work again the way they were intended.

The answer appears to be no.

The glory days of the downtown Bay, once described by this newspaper as a “completely modern and efficiently equipped mercantile plant” have long since passed. Like other big downtown department stores in other North American cities, the question now is what to do with it.

The only sure thing anyone can say is that it will never be a department store again.

Secret report too sensitive for release

There’s a report kicking around called The Bay Redevelopment Strategy. It was commissioned by CentreVenture Development Corporation, the city’s downtown development agency.

That report is secret.

CentreVenture Development Corp. president Ross McGowan said he can’t release it because of its sensitive nature.

Research for the report started late last year after McGowan asked the Hudson’s Bay Company to postpone any decisions on closing its money-losing downtown store to allow the corporation, city and province to finalize a plan to redevelop it.

McGowan said those at the table, including an out-of-town developer, want HBC to continue to have a strong, visible presence in Winnipeg’s downtown — The Bay used to own what is now downtown Winnipeg back in the fur-trade days.

“We’re working with the province and The Bay on a strategy, if you will,” McGowan said. “Our desire first and foremost would be to see The Bay continue to have a presence in the downtown. I think we’ll focus a lot of energy on that.

“One of the problems is that everybody is looking for ‘a’ solution. There is no one solution in my humble opinion. This is something that has five, six or eight or 10 pieces to it that makes it work.”

Our history is directly tied to the 400-year history of HBC and its role in the early fur trade, the settlement of Manitoba, the opening up of the west and the creation of what is now Winnipeg.

The provincial government says the main reason The Bay Redevelopment Strategy is secret is that it contains financial information that could put the province in a bit of a pickle. If that information were to become public, it could compromise future negotiations on how the store could be redeveloped and how much the province would be on the hook for paying for it.

The second key part of information in the report has to do with how the store could be redesigned.

One idea would see all or part of the store’s interior gutted — essentially hollowing out what was built in the 1920s and building a new office tower inside the old store’s four massive exterior Tyndall stone walls. One example of what it could look like is the old Tip Top Tailors Building in Toronto. Also built in the 1920s, it was converted to condominiums a decade ago. Another is the Woodward’s building in Vancouver. Built in 1903 as a department store, it’s now office and residential space.

“The solution is to gut it and preserve the exterior of the building and build a brand new structure or structures inside that envelope,” McGowan said. “The days of an 80,000 square-foot floor plate are long gone. What do you do with it? I’d tear the inside down. I would not tear the building down.”

The province wants to keep any possible redevelopment plan under wraps for the time being because it’s too early to begin the debate over what to do. There was a similar debate in 2001 when the old Eaton’s department store at Donald Street and Portage Avenue was slated for demolition to make way for the MTS Centre, now home for the National Hockey League’s Winnipeg Jets.

There’s also this: The Retail Insider blog reported last month HBC wants to close the downtown Winnipeg store.

“Our source tells us The Hudson’s Bay Company is seeking to transfer ownership of the building to the Manitoba government in exchange for tax benefits,” the blog said. “Hudson’s Bay would like to sell the building, but its value is limited due to the estimated $8 million/per-floor renovation cost to convert it to offices.”

The downtown Bay is about 560,000 square feet in total — about 80,000 square feet per each of the six storeys. And the $8 million per floor would do little more than bring the building up to code.

“On the surface of it, it does not make economic sense, it makes no more economic sense than a proposal to adaptively reuse The Bay,” McGowan said. “If you’re going to spend that kind of money for Class A office space, then you should end up with Class A office space.”

An additional and unknown cost is preserving the store’s historical or heritage value, like the elevators and the fading mural of the Red River settlement above them.

A decade ago, Manitoba Hydro looked at the store as it made plans to relocate its headquarters downtown.

Steep renovation costs were not the issue — the problem was Hydro could not meet its energy efficiency target with the building. Hydro could not change the store’s exterior to allow the installation of additional windows, which would have been key to decreased lighting requirements. Instead, Hydro built its $278-million, 18-storey office tower down the street.

McGowan said closure of The Bay’s downtown store is not as imminent as rumoured, and that the company is committed to keep talking.

“It does not mean it might not close in a year, but my sense is from everyone around the table, everyone wants a solution,” he said. “The solution needs to be a made-in-Winnipeg solution and it’s a much longer term vision than simply repurposing it as a retail operation and throwing some government offices in it.”

New life for old buildings

There is no template for what to do with old department stores.

Dozens of other cities in Canada and the United States have confronted the problem over the past 20 years — the decline of the profitability of downtown department stores started in the 1960s and has escalated since with the proliferation of suburban shopping malls and big box stores and their even bigger parking lots. Internet shopping is the last nail in the coffin.

Robert Warren, formerly of the Asper School of Business at the University of Manitoba and now with the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin, said governments, for the most part, tend not to get involved in the redevelopment of existing buildings, such as old department stores.

Warren said the preferred method is for governments to champion major projects aimed at transforming bad neighbourhoods for the public good, such as the North Portage Development and the building of Portage Place and The Forks.

But the Bay’s downtown store is different, he said.

“The Bay downtown is a special case in that it is a great example of a particular architectural style and is one of Winnipeg’s signature buildings. It is also located in a highly visible area of the downtown and would send the wrong message about the city if it were to be vacant for a long period of time. For these reasons, I think some form of provincial-city funding will be crucial.”

But for what?

The Bay approached the University of Winnipeg a year ago, saying it would sell the store to the university for as little as one dollar.

The U of W was interested in the property at one time. It had considered using 2 1/2 floors to establish a national centre for aboriginal study, arts and culture.

Nothing came of the offer and a U of W spokeswoman recently said the university hasn’t had any discussions about the store property for a while.

The province has muttered about the possibility of the new Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation moving into a redeveloped Bay, but not if the cost of such a move undermines the rationale of amalgamating the two Crowns in the first place. Simply put, it can’t cost the deficit-challenged NDP money it doesn’t have.

The Manitoba Lotteries Commission and the Manitoba Liquor Control Commission were combined a year ago with the expectation the two Crown agencies operating as one would save taxpayers money. The two agencies still operate out of different locations. There is some frustration that to truly operate as a single entity, they’ve got to do it under one roof.

Warren said a redevelopment of the store should focus more on supporting a private developer in transitioning the building to a new use, such as expanded space for the U of W, mixed residential, office and retail space.

“They could bill this support out under the heritage concept or as part of downtown’s continuing redevelopment as a place where people live and work,” he said. “In my mind that is why replacing the old Eaton’s building with the MTS Centre made so much sense. It ensured the city did not have a large, vacant building in a highly visible location of downtown. As we have seen, having MTS Centre has boosted the city’s morale and driven other development.”

See below for a roundup of what’s happened with department stores in other North American cities.

More dialogue needed: WAG

There’s a bunch of folks across the street also curious about what will happen to The Bay.

In fact, it’s been on Winnipeg Art Gallery executive director Stephen Borys’ mind since he was appointed in 2008.

There was a time when the WAG contemplated locating its new Inuit Art and Learning Centre at a refurbished Bay store, but not anymore. The WAG has already decided to build the new three-level $35-million gallery on the site of the WAG’s current studio building (the adjacent former Mall Medical Building) to showcase the largest public gallery collection of Inuit art in the world. The size of the new building is about 50,000 square feet, enough to fit on one floor of The Bay with considerable room to spare.

“That’s the question. What’s the benefit of the WAG being on two sides of the street or is it better for us to consolidate to enhance our visitor experience here on our property?” Borys said.

The other concerns for the WAG are permanency and relevance. If it moved its Inuit collection into a renovated Bay only to see that renovation not work, then what? The collection would be mothballed and The Bay would be empty again.

“When a museum moves into a space, we need to think long term. Our board felt strongly that we want The Bay to stay and we’d like to contribute anyway we can, we didn’t see the WAG having a real presence in that building,” he said.

Part of the WAG’s collection includes pieces from the exhaustive Hudson’s Bay Collection of Inuit Art. HBC started collecting Inuit handicrafts in the 1930s as a way to expand its business.

Borys also said he believes it would be a shame to entirely gut — he calls it a facadectomy — the building’s interior and only save the outer walls.

“Is it going to be a complete gutting and all that’s left standing is a stage set?” he asked.

“What I would love is that there be more dialogue with all the players. I think that has been lacking. There’s been a lot of one-way and two-way conversations, but rarely have all the players and supporters been at the same table. That would be so useful.”

$1 million a year for heat, light

CentreVenture’s McGowan said there’s room for the art gallery and the U of W to be involved in the store’s redevelopment, but only to a point.

“The problem is in the economics of whatever deal it is,” he said, adding there will continue to be an enormous operating cost to keeping the building’s lights and heat on during the winter, estimated to be about $1 million a year. There are also the taxes. (The building is currently assessed at $14,385,000, according to 2013 values.) The store’s annual revenue barely covers those expenses and other utility costs.

“I think there’s as much of a stumbling block with that as with any other cost associated with it,” McGowan said.

Those numbers, and the costs of redeveloping the building, do not make it a slam dunk that employees with the new Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation will be moving into where the appliances and home linen departments are still located.

McGowan said the province should first go to the marketplace to see what other opportunities there are for a centralize Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation, what the costs will be and what the Crown agency will get out of it, McGowan said.

On the flip side is how patient The Bay will be in waiting for a decision.

“It’s a very delicate problem, this whole thing,” McGowan said. “The discussions haven’t fully played out.

“The key I think is to put this lotteries and liquor thing to bed once and for all. Either they go in there and save The Bay or they don’t and we all look at each other and say, ‘OK, now what?’

On the day the downtown Bay opened at 9 a.m. Nov. 18, 1926, it was the largest reinforced concrete building in Canada. The total budget for the store’s construction was $5,968,000. In the slideshow above, find a snapshot of what went into the six-storey construction more than a year earlier.

Hard times for castles of capitalism

Downtown department stores once were the centrepiece of almost every North American city.

Built tall and strong, these castles to capitalism sold everything to eager consumers, from blankets to fine china to books to meat to coal to clothing for the entire family.

No longer.

The automobile and growth of suburban shopping malls, like Polo Park in 1959, have slowly chipped away at these downtown edifices. Big retailers responded by also moving out to the malls, in the process shrinking the size of their downtown operations or getting rid of them completely.

In cities where department stores were closed, politicians and planners have scrambled to decide what to do with these once mighty and bustling buildings.

In Winnipeg, it’s the Hudson’s Bay Company’s department store at Portage Avenue and Memorial Boulevard. The Eaton’s store at Portage and Donald Street was knocked down in 2002-03 to make way for the MTS Centre.

Here’s what 10 other cities have done with their old downtown department stores:

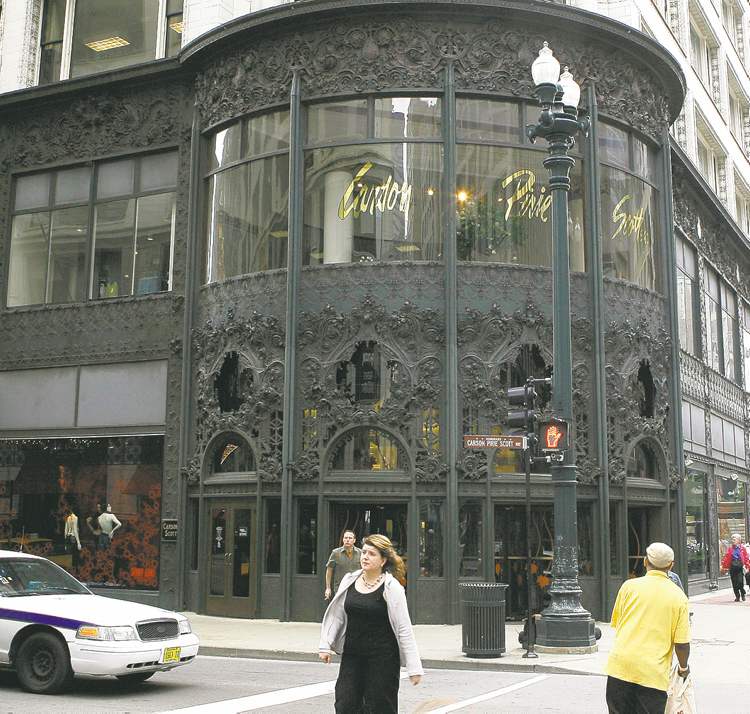

Carson’s in Chicago

A Chicago landmark, Carson Pirie Scott & Co. opened in 1904 and operated as a nine-storey department store until it closed in February 2007. The 600,000-square-foot building was renamed the Sullivan Center and has been refurbished. Its tenants include the Art Institute of Chicago and Gensler, an architecture, design, planning and consulting firm. Target took over two floors July 26, 2012.

Macy’s in Pittsburgh

Macy’s has cut the number of floors at its downtown store to six, consolidating departments under a plan to sell the 13-storey building or at least rent some of its upper floor space. The building, which for decades housed the Kaufmann’s department store, has been up for sale since July 2010.

Macy’s in St. Paul

Macy’s has announced it will close the 362,000-square-foot store this spring as part of a wider announcement to shut down underperforming stores, including ones in Pasadena, Honolulu, Houston and Las Vegas. The debate in St. Paul is whether to build an office tower at the site or lure another retailer such as Target to take it over.

Eatons/Sears in Vancouver

The seven-storey Sears store at Granville and Robson closed in October. The plan calls for the 650,000-square-foot building, formerly an Eaton’s store, to be gutted in advance of American retailer Nordstrom moving in and opening its doors in the spring of 2015. Nordstrom will use three floors of the building for its retail operation. There will also be an office component.

Lasalle’s in Toledo

The Ohio department store opened in 1918 and became a Macy’s in 1981. Two years later it closed. It sat vacant for 13 years. In 1996, developers converted it into apartments and retail space as part of the Madison Avenue Historic District development.

Higbee’s in Cleveland

The 10-storey department store opened in 1932 and was featured in the 1983 movie A Christmas Story. It closed in January 2002. The main, second and third floors were restored in 2007 to office space for the Convention & Visitors Bureau of Greater Cleveland and the Greater Cleveland Partnership. The building was again remodeled in 2011 and opened on May 14, 2012 as the Horseshoe Casino Cleveland.

Filene’s in Boston

The downtown department store opened in 1912 and closed in 2006 when Filene’s merged with Macy’s. The building was bought by a New York developer under a $700-million plan to build a 39-storey office tower, including a hotel, restaurant, condos, and retail space. Only the facade was protected under a heritage designation. This allowed developers to demolish the building’s interior, leaving the exterior to stand on its own. The project ran out of money in the 2008 economic collapse. The site has remained gutted since then, although signs indicate the project could start again.

Nordstrom’s in Indianapolis

It closed its 210,000-square-foot downtown department store July 31, 2011, because of poor sales. Reports say finding a replacement has been difficult because the space is so large.

Strawbridge & Clothier’s in Philadelphia

The flagship store, opened in 1931, closed in 2006. The company that owns The Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News moved its newspaper offices into the renovated store building in July 2011. The upper floors had earlier been converted to offices.

Miller & Rhoads in Richmond

The Virginia department store closed in 1990 due to increased competition after about 100 years in business. In 2006, work began on a $100- million project to convert the long-closed department store into the 250-room Hilton Garden Inn and 130 apartments or condominiums.