The starry-eyed boys of summer

The major-league dreamers in Winnipeg Goldeyes uniforms endure long, hot bus trips and meagre paycheques to keep faint hope alive that they'll eventually get a chance to play ball in The Show

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/08/2012 (4873 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

KANSAS CITY, Kan. — Darkness has fallen in Kansas City, when a Winnipeg Goldeyes player-who-will-not-be named steps onto the team bus that sits idling beside CommunityAmerica Ballpark. He’s leaving behind a local girl who’s there to see him off. How sweet.

But teammate Chris Salamida, wearing an Atlanta Braves cap and a mischievous grin, is waiting to pounce.

"Did you say goodbye to Britney?" Salamida cooed. "Did you tell her, ‘Kiss me, baby, one more time?’ Because you know you have to say that at least once, right?"

Of course, as any self-respecting teenybopper could tell you, Salamida had the lyrics wrong to the Britney Spears ditty. It’s ‘Hit me, baby…’ But he’s improvising.

"You have to admit that was good, though," he continues to chide. But the player-who-will-not-be named ignores Salamida as best he can and continues to the back of the bus, slowly being occupied by Goldeyes who’ve made a quick run to a nearby Sonics for burgers and shakes before departure for a five-hour journey through the night to Sioux City, Iowa.

This is minor-league ball, after all, where you leave 0-for-4 and the girls in the rear-view mirror. On to the next town.

Salamida begins to prepare for the trip. Out come the baggy sweat pants. A pull-over kangaroo sweater. Oh, and giant, puffy pink slippers.

"They’re like Snooki’s," he explains, unapologetically, to a new passenger. "They’re comfy. Soft and squishy."

On the bus, a few players are sleeping in seats-turned-to-double bunks. Some are engrossed in a card game called Plunk.

Pitcher Alex Jones is watching an episode of South Park on an iPad resting on his belly. Manager Rick Forney and hitting coach Tom Vaeth are curled up in their seats at the front, sound asleep.

Salamida is a right-handed starter for the Goldeyes, a member in good standing of the American Association of Independent Professional Baseball. He’s toying with the idea of being a firefighter someday, but at 28, the native of Albany, N.Y. has spent the last three seasons in Winnipeg.

"It’s hard to walk away from baseball," he says. "I miss the guys, I miss the camaraderie. I even miss the dust coming off the seats on the bus. I’ve said I was going to retire the last three years. And every year I come back."

Salamida found his way to Winnipeg like almost every one of his Goldeyes teammates. Because major league baseball spit them out. And the independent minor leagues were the only alternative left.

Besides getting a real job.

"It wasn’t the easiest thing," Salamida said. "It gives you a tough feeling in your chest. Then it gives you a fire under your ass to prove everybody wrong."

It’s a common refrain repeated over a six-day journey with the Goldeyes; a sometimes sweltering tale of life on the road, a story of what these players sacrifice to chase their shared dream, and what they leave behind.

There’s the endless hours on the bus. The belly laughs. The boredom. Oh, and the Britneys.

But, always, the baseball.

And it begins with two men out, in the top of Kansas…

Paul Edmonds is flying south on I-35 in a gold SUV bound for Kansas City. It’s early afternoon and the thermometer on the vehicle dashboard is registering an outside temperature of 33 C. The forecast high will tease 40 C.

Another gauge on Edmonds’ vehicle reads 18,125 kilometres and counting. That’s the distance the veteran Goldeyes radio broadcaster has logged so far in the 2012 season — kicked off by an odometer-reeling, 17-day road trip to start the year in Texas.

And it’s only early August. By the time the last pitch is thrown, Edmonds will have driven more than 25,000 kilometres, mostly alone, following a team he has faithfully covered for 18 years.

Edmonds carries with him a pillow and blanket at all times; necessary gear in a league where teams stretch from Winnipeg to Chicago to Amarillo, Tex., where a sign posted at the stadium gate cautioned: "It is a criminal offence to carry a handgun on a premise where a sporting event is taking place." Said Edmonds: "I realized I was not at home anymore."

The broadcaster/long haul-driver has been known to drive up to 15 hours straight. It figures that Edmonds, in another life, drove semis. He still has a Class-1 licence.

"If people knew how many rest stops I’ve slept in over the years, they’d be shocked," he said. "It’s very solitary, but it hasn’t worn on me. And at the end of the day, the reward is to call a baseball game. And at this point, I wouldn’t know what else to do."

Edmonds first joined the Goldeyes as an announcer in 1995, the club’s second season of existence in the now-defunct Northern League. Over 17 plus years, he’s missed just one game: July 16th, 2002, for the birth of his son Mark.

By now, Edmonds’ excitable delivery is synonymous with baseball in his hometown. A home run: "You can look up, pucker up, and kiss it goodbye!" A strike: "Right down Portage and Main."

And, of course, "Fish win! Fish win!"

Countless fans might not recognize Edmonds if he passed their drive-thru window. But they’ve listened to him for years now planting and harvesting crops, barbecuing in the backyard or relaxing at the lake. Said Edmonds: "You really have a conversation with someone on the other end of the radio or computer. You just don’t know who they are."

In action, behind the microphone, Edmonds is a one-man band; looking up stats, keeping score, checking out-of-town scores on his computer, peering with his binoculars for activity in the bullpen — all while continuing to carry on his "conversation" with fans, on most nights for more than four hours.

He runs mostly on fast food and Red Bull.

Hence the lead-footed race to Kansas City, where Edmonds will set up shop at CommunityAmerica Ballpark to call a three-game set with the Kansas City T-Bones, who are one of two teams vying with the Goldeyes for a wild-card playoff berth.

It’s going to be a scorcher. Literally. Temperatures in Kansas City the previous week were upwards of 43 C. If the summer-long drought in the U.S. Midwest hadn’t already baked crops into submission, you’d think the endless rows of corn lining I-35 would be popping in the field.

"I think you’ll have a good idea of what cremation is like," Edmonds deadpanned, "when you get out of the car."

The Goldeyes, however, were feeling the heat long before reaching the Missouri border, leaving Winnipeg at 10 p.m. Monday and arriving in KC around noon Tuesday. It’s a critical swing, after all, for a club that has been going sideways after a promising start to the season.

The team is beat up, just a couple games ahead of the T-Bones and St. Paul Saints in the AA wild-card race and falling behind the North division-leading Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks, the Goldeyes’ arch-nemesis, at an unsettling rate.

Goldeyes manager Forney, a former pitcher who has been with the organization since 1997, doesn’t hide the sense of urgency.

"It’s a pretty important trip right now," Forney conceded, as his boys of summer settle in the visiting locker-room in Kansas City, just beyond the centre-field fence.

"We could do ourselves a big favour by winning two or three ball games… you can breathe a little bit easier. It’s hard to play catch-up. But if you spit the bit here, it could get interesting."

Forney doesn’t want interesting.

"I hope our team is up for it," he said.

Maybe that’s wishful thinking. For the past month, Forney’s Goldeyes have been struggling. A 30-games-in-30-days stretch — coinciding with a pair of call-ups and a handful of injuries — has left him with a lineup of walking wounded. Worse, Forney’s bullpen of relievers has been anything but, of late.

Before the game, Forney is already hunkered in his tiny dressing room, working the phones for able-bodied closers. With a trade deadline set for Aug. 24, it’s not unusual for the manager to spend five hours a day scouring rosters, crunching salary cap numbers and pitching proposed trades.

"It becomes 18-hour days," Forney said. "It can consume your life at this time of year. It’s when people are hurt, man. That’s why my forehead keeps getting bigger."

Sure, Forney can make some moves down the stretch. But with a salary cap of $115,000 for the entire season, his options are limited. His lot has been cast with a disparate collection of young men: a few raw rookies, a couple globe-trotting veterans who’ve seen the big leagues from the inside, but mostly guys like Todd Privett, a 26-year-old pitcher from Salt Lake City, Utah, who last winter was stocking grocery shelves after being released from the San Diego Padres system. That’s when Forney called.

Privett has a tattoo of the Major League Baseball logo on his left calf. He has a wife staying in a hotel back in Winnipeg with his two-year-old son, Nolan Ryan Privett.

Ask Privett how much money he’s making with the Goldeyes and he replies: "Do I have to tell you? Not very much."

But he adds, "Every day I enjoy it as much as I can. I know I can’t do it forever. But I keep trying."

Besides, Privett asks, "Everybody that shows up for the game, how many guys would like to be in my shoes?"

Interesting question. Because if you look beyond the smart uniform, behind the locker-room door and ride the bus, the romantic notion of a carefree existence as a minor league ball player is soon challenged by the hard reality of an unforgiving game where numbers don’t lie. They don’t coddle, either.

"These guys, a lot of them are going broke doing this," says Goldeyes hitting coach Tom Vaeth, who has been riding shotgun with Forney since 2003. "A lot of them are putting off their life, really. A lot of things are put on hold. I’m sure a lot of them have college loans to pay. At some point, they’re going to come due. And it’s tough for some of these guys to step in and find good employment after the fact."

In the realm of professional baseball, the independent leagues such as the American Association are a purgatory of sorts: one phone call away from affiliated ball — the farm system for major league teams — and one tap on the shoulder from stocking grocery shelves in Salt Lake.

For the most part, few players arrive in the association by choice. In almost every case, they’ve been rejected, released and had their hearts broken.

"You’re managing failure, in a lot of ways," Vaeth notes. "Not failures. You’re doing the best you can to build them up so they can get back (to affiliated teams). There’s a lot of TLC."

And for some, there is no Plan B.

Jon Weber is a stocky bull of a man. Now 34, he’s been playing professional baseball for 14 years. He knows nothing else.

"That’s all I am," Weber readily admits. "I’m a baseball player 100 per cent. I’ve tried to get away from the game, I’ve tried to get other jobs. I just can’t do it.

"Minor league baseball, it’s not made for everybody," he adds. "It’s tough. Some guys stick it out for a couple years, then they get a job at their dad’s company or get something better because they know they’re not going to make it. I don’t have a choice. I’ve got to play. What am I going to do? Go work with my dad digging ditches? Hell no."

Last off-season, Weber tried to land a job as a longshoreman, but that fell through.

"You know the reason?" he ventures. "Lack of experience. No shit. I’ve been a baseball player all my life."

Weber has played winter ball in Mexico and Columbia for several years. Have bat, will travel. He’s been caught in drug-war gunfights in Mexico. In Columbia, bandits tried to hijack the bus after the players were paid in cash.

Weber is a baseball mercenary. He’ll follow the money, and the reasons are literally etched on his body: A tattoo for wife Christie on his left wrist, one for son Dylan, 8, on his left bicep and another for daughter Marin, 5, on his left shoulder.

Perhaps that’s how the gregarious veteran, who spent several years in Triple A, one promotion from the majors, manages to shake off a recent dry spell at the plate that left him hovering around .300. That’s a decent average for the average ballplayer. But Weber isn’t paid to be average.

"I mean, I’ve got a wife and two kids at home. This is easy," Weber reasons, when asked how a hardened baseball mercenary handles a slump. "Think about if I was at home with no job and a wife and kids and mortgage. Now that’s stressful."

Besides, he assures himself, "It’ll come."

Indeed, in a league where paycheques are modest, if not below poverty-level wages, the ultimate currency is eternal optimism.

Andrew "Ace" Walker has been the Goldeyes go-to pitcher now for going on five years. Now 29, the God-fearing righty from Prague, Okla., holds the franchise record for most career wins. In 2009, Walker was the Northern League’s pitcher of the year, a hard-earned honour the former Texas Ranger prospect reasonably thought might get him another look. But…

"I didn’t get one phone call, not one spring training invite, not one ‘Hey, let’s see you pitch’," Walker says. "I was the best pitcher in the league, and it meant nothing. If the best pitcher in the whole league can’t get picked up, what’s that saying?"

Walker is perched on a chair in the bullpen of CommunityAmerica park on a day the stadium temperature is set to broil. Unlike a lot of his teammates, Walker knows what awaits his life after baseball. He’s an accomplished artist who two years ago opened up a business back in Prague, where he paints murals, does graphic design, oil paintings… "Whatever pays the bills," he says.

But for now, Walker prefers to paint the corners on home plate. He keeps pitching, keeps winning, waiting for that phone call to come. Time, however, is Walker’s opponent now.

"It’s hard when reality sets in and that’s where I’m at, thinking about the future and wanting a house and wanting retirement and health benefits," he says. "Have kids and kind of be stable. I want to form relationships with people that will last a lifetime and aren’t so periodic. I’m looking forward to that chapter, whenever it happens, whether it’s after this season or next season or the season after that.

"I just don’t think it’s a family-oriented game for the player. That might seem strange to say, but it’s hard. When I was 21, and I first got drafted, I was like, ‘I’m going to be a Hall-of-Fame pitcher and I’m going to pitch for 20 years.’ I had such tunnel vision on that. As I’ve gotten older, it’s kind of been, ‘I want to have a family. I want to have a summer.’ Or ‘I want to be able to go to my kid’s baseball games.’

"Maybe God knows my heart better than I do. My priorities have kind of shifted.

"Whether they would have shifted if I was in the big leagues, probably not. Because you’re making the money. You’re supporting them (the family). You’re a world-class athlete."

It’s not just the art business waiting for Walker back home. A few years back, he was at Prague’s annual Kolachi Festival, the town’s celebration of its Czech heritage. There, with the polka music blaring, Walker first laid eyes on Paige Sullivan, the Kolachi Queen of 2007.

"I saw her," Walker says, "and that was it. She had to be mine. A very sweet girl with a big heart. That’s something, I hadn’t really dated a lot."

Sitting alone in the bullpen of an empty stadium, Walker leans forward, just a little, and lowers his voice.

"I hate to say it," he says, "but in baseball you don’t meet a lot of wholesome girls. I try to stay away from those girls as much as possible."

— — —

TRUE STORY: After three scoreless innings in the first game in K.C., a reporter embedded in the Goldeyes dugout is writing down questions to ask Forney later, jotting down the sentence, "Are you superstitious?"

Seconds later, Forney ambles up and politely tells the scribbler, "You’ve got to get to the other end of the dugout. We’re not getting any runs with you here."

As if on cue, the first batter to lead off the top of the fourth for Winnipeg, third baseman Amos Ramon, launches a solo home run to give the Goldeyes a 1-0 lead.

At the end of the inning, Forney, who serves as the third-base coach while the Goldeyes bat, walks back into dugout and tells the reporter, "Now you’ve got to go back to the other end of the dugout to keep them from scoring."

And so it went.

Lesson No. 1: For all the raw, incontrovertible numbers than define baseball, the game is rife with voodoo.

The night before every start, Ace Walker eats pizza. He always crosses the chalk line to the mound left foot first. Pitching coach Bill Pulsipher, now 38, has worn his sliding shorts inside out since high school.

If the announcer Edmonds eats lunch at Cheeseburger in Paradise on Tuesday and the Fish lose that night, he won’t be back. "No wins there," he reasons.

If the Goldeyes get a string of runs in an inning, the next inning you will hear the words, "Same seats."

The most super of the superstitious, however, is Salamida, who has worn the sock on his left foot inside out (honest) since he was in junior high. All day, every day. Something about turning his ankle running the bases. For his first two-plus years in Winnipeg, Salamida wore the same clothes to every game he was scheduled to start. Until he started this season 2-5. A new ensemble was in order.

"Baseball is that kind of game because it’s built on failure," Pulsipher said. "So if you’re doing well, do the same things, because you know just around the corner failure is waiting."

Yes, baseball can break hearts. But it’s also a game of childish pranks, endless comical banter and time-worn anecdotes that characterize an occupation where the employees have too much idle time on their hands.

EXHIBIT A: Prior to a game in Sioux City, Edmonds is passing time in the Goldeyes locker-room, when he grabs a handful of chips off the clubhouse table. Enter Forney, who catches Edmonds with his yap full.

"I don’t see you paying clubhouse dues," Forney snaps, while simultaneously reaching into the locker of relief pitcher Zach Baldwin to grab a pinch of chewing tobacco.

"Oh," Edmonds counters. "You’re the same guy taking a chew from some guy’s pouch!"

"I paid for that," Forney bleated.

Edmonds is broadcasting on high volume now. "I’ve never seen any money exchanged! How do I know you paid for that?"

Forney has had enough.

"Go up in the radio booth and run your mouth," he sniffs. "That’s where you get paid to run it."

The manager walks by a reporter. Wink.

EXHIBIT B: Prior to Game 2 in Kansas City, Forney left his office and sauntered over to tell outfielder Kyle Day, "You’re DH-ing (designated hitter) today."

Forney was stark naked at the time. Except for his watch and a pair of shoes.

"They try to take the information with a straight face," the manager noted, "but when you see a 6-foot-4, 260-pound man walking in the clubhouse who looks like a polar bear with nothing but tennis shoes on… how could you not laugh? You could imagine what that sight looks like."

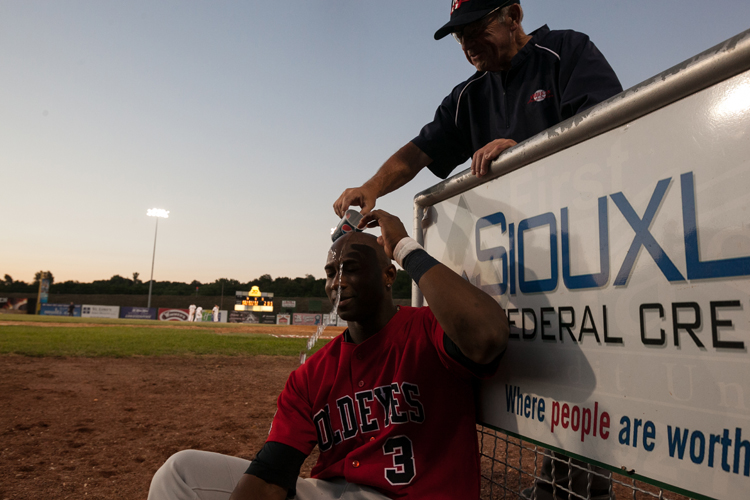

EXHIBIT C: A few days later, just before the opening pitch in Sioux City, here’s the scene: Starting pitcher Dexter Carter is at the top of the dugout, wondering what colour of jersey he should choose. "We wearing this?" he asks no one in particular, of his blue top. "Red? I’ll go out there naked if I have to."

Weber is pacing the dugout, pumping himself up to play in front of a modest gathering at Lewis and Clark Park: "There’s dozens of people here to see us!" he is saying, "Dozens!"

Just a few feet away, Amos Ramon is telling the story of pulling up to a fast-food drive-thru the night before: "We said, ‘Can we have a half-dozen nuggets?’ They said, ‘We don’t have that. We have six, 10 and 20.’ So we said, ‘OK, we’ll have six’. I’m not kidding."

Then there’s Pulsipher’s eight-year-old son Leyton, a pint-size pistol who should be in the movies. Leyton, along with his older brother Liam, are serving as the Goldeyes’ bat boys on the trip.

So Goldeyes athletic therapist Shane Zdebiak is asking Leyton, "What grade you going into?"

"Three," he replied.

Standing there, wise-guy Salamida pipes up, "Kindergarten?"

The kid, about one metre tall, looks up at the pitcher and says, "Good for you."

Wait, one more. Bellied up to a bar in a Sioux City hotel, it’s getting near last call. And Forney is asked if he can recall his favourite story about a meeting on the mound. He thinks for a second.

Then Forney remembers a fireworks night in some ballpark (he can’t remember which) when he was the Goldeyes’ pitching coach at the turn of the century. A righty named Chris "Spider" Webb was on the mound for the Fish. Former fan favourite Ryan Robertson was catching.

Webb throws a pitch. Boom. Home run. The fireworks start going off in the outfield.

Next batter. Boom. Another home run. The fireworks goes off again.

Before the next batter can step to the plate, Forney slowly saunters from the Goldeyes dugout to the mound. Robertson comes from behind home plate. The three of them stand there for a few moments, kicking dirt. Finally, Webb says, "Anything you want to tell me, coach?"

"Not really," Forney replies, with his Maryland accent. "I’m just waiting for the fireworks guy to reload."

— — —

Chris Roberson was six years old when he was first handed a bat in T-ball.

"Just hit it and run," they told him.

Roberson has been running ever since. At 32, the Goldeyes veteran from Oakland is hitting at a .350 clip.

Roberson is a minority in independent baseball; one of the players who have reached baseball’s Everest. The big leagues.

The sleek outfielder made his major league debut on May 12, 2006. The call came the night before, jolting him out of bed.

"You’re going to the big leagues," his manager with the Triple A Reading Phillies, told him. "Congratulations. Now pack your bags, the flight leaves in four hours."

The next day, Roberson walked into the Phillies locker-room in Cincinnati. When he saw the Phillies jersey hanging in his stall with "Roberson" on the back, No. 29, he was speechless.

"I just looked at it for five, 10 minutes," Roberson recalled. "I kept going, ‘Wow’. It’s one of those moments where there’s not too many words to describe it. It’s the stuff you dream about as a kid. I was thinking, ‘So this is what it’s like.’"

Roberson started in right field. The first out of his major league career was a screaming line drive off the bat of Reds’ superstar Ken Griffey Jr.

Roberson’s first trip to the plate was surreal.

"Everything was kind of slow motion," he said. "My first at bat I saw every lace on the ball. I was looking at the ball so much I couldn’t even swing. That’s how unreal it was the first day."

Over two seasons, Roberson played 85 big-league games for the Phillies. He was paid $36,000 a week. Now? "You don’t want to know," he says, smiling.

Still, Roberson can scratch out a living. Top players in the AA make between $4,000 and $5,000 a month. Journeymen like Roberson and teammates Yurendell de Caster and Weber can make up to $10,000 a month playing winter ball in places like Mexico, Columbia and Venezuela.

Roberson admits his taste of the majors, where he’d meet the likes of actress Eva Longoria and rapper Sean P. Diddy Combs at VIP parties, can make riding the buses of independent ball just that much more challenging.

"It was a big adjustment," the amiable outfielder concedes. "The people who haven’t seen it (the majors), they don’t know. It’s hard for me sometimes to sit back and wonder what’s happened to my career, taking turns like this. Yeah, it’s hard. Seeing guys (former teammates) signing big contracts where you had the same talent. And you played with those guys so many years through the minor leagues. But I don’t get bitter about it. That’s just the way it goes sometimes."

There are no big league airs around Roberson, who has a ready smile. But his desire to beat the odds and find his way back into affiliated baseball hasn’t ebbed. In fact, the opposite might be true.

"It’s even more now," he says. "I’ve played at that level before, I want to finish at that level. That’s the goal now. When my legs and my knees go out, I’ll stop. Or when my heart doesn’t feel it anymore, I’ll stop."

But there’s one man in a Goldeyes uniform who has seen more big league action than anyone on the bus. And he’s not a player.

Bill Pulsipher was once a can’t-miss prospect for the New York Mets, and in 1995, at age 21, the southpaw pitcher was the youngest player in all of major league baseball.

The world was Pulsipher’s oyster. And the oyster went bad.

Pulsipher still remembers the exact moment, in April 1997, when everything went wrong. He was throwing in the bullpen for the Mets’ Triple A team in Norfolk when the first rush of anxiety hit.

He couldn’t stop the jitters. His hands sweated. The plate was invisible.

"The only thing in my life that was normal to me — being on the mound, my safe place — felt completely foreign to me," Pulsipher says, on a lazy Sunday in a dugout in Iowa.

Over the next seven years, the once can’t-miss-kid had a .500 record at best with his demons. He tried to outrun his anxiety, on and off medication. And, eventually, after appearing in 100 major league games with six major league teams, he ran out of time.

At one point, prior to making a brief comeback with the St. Louis Cardinals in 2005, he took a job tending the Mets’ Triple A field in St. Lucie, Fla. that he once dominated as a player. He was paid $8 an hour.

These days, the Goldeyes pitching coach tells his players who tend to roam, "No matter how crazy you think you are, you’re not even close. That’s child’s play from what I’ve done. And you reap what you sow."

When Pulsipher is asked if his career is a cautionary tale for young Fish, he instantly replies, "Abso-freakin’-lutely."

Pulsipher isn’t much for regrets. The anxiety attacks have abated. He’s a family man now, with Liam, Leyton — both boys have the initials LHP, the lineup designation for left-handed pitchers — and wife Michelle in tow on the trip through K.C. and Sioux City. And he’s determined to start the second phase of his baseball life as a Goldeye.

Like Weber, Pulsipher readily admits the game is all he knows.

"I sweat resin," the old pitcher says, "and bleed pine tar." And he believes his 20 years of accumulated knowledge, the good and the bad, would be wasted if he simply walked away.

"You learn from your mistakes, or what’s the point?" he reasons. "You either fold up or you don’t. I don’t."

Still, if you’re looking for a heartwarming, happily-ever-after tale, skip Pulsipher’s locker.

"It’s not about rainbows and butterflies. It’s a difficult lifestyle, man. I call it a gift and a curse. On one hand, this (professional baseball) is every little boy’s dream. The curse is dreaming of 20 years in the big leagues… and here you are."

That’s why you won’t catch Pulsipher trotting out his big league greatest hits on a loop. He might have struck out major league home run king Barry Bonds three times in one game, but you’ll have to pry it out of him.

Pulsipher says, with not a whiff of self-pity: "I feel like my big league story never happened… or hasn’t happened yet."

That last line could summarize almost any Goldeyes’ biography ever written. All of them, in their wildest dreams, could tell you how they’d like their story to end.

For 29-year-old reliever Craig James, it’s facing "the most bad-ass righties and striking them out."

For 26-year-old outfielder Kyle Day, it’s "a nice hard single up the middle. Just rounding first, knowing you’ve got the hit. That would be pretty special."

Special, and far from unprecedented.

Over the years, a handful of Goldeyes have risen to the ranks of the major leagues. In 2002, pitchers George Sherrill and Bobby Madritsch were sitting in the Goldeyes bullpen. In 2004, both were in the big leagues with the Seattle Mariners. In 2009, Sherrill made the 2009 MLB all-star game as a member of the Baltimore Orioles and signed a one-year, $2.5 million contract.

Pitcher Jeff Zimmerman was in Winnipeg in 1997. In 1999, he appeared in the MLB all-star game wearing the uniform of the Texas Rangers. Earlier this year, Goldeyes lefty Fabian Williamson was signed by the Atlanta Braves organization (Single A).

Consider: Last February, Sioux Falls catcher Eddy Rodriguez was signed by the San Diego Padres. On the very night the Goldeyes were on the bus from Kansas City to Sioux Falls, Aug. 2, Rodriquez made his major league debut against the Cincinnati Reds.

He hit a home run in his first major league at-bat.

Sitting in the dugout in Sioux City, Forney cast his glance over his charges and says, "How do you know one of these guys isn’t going to be the next Eddy Rodriquez or George Sherrill?"

Right place, right time.

Yet for a busload of young men who literally give their right and left arms to be somewhere else, the place they are now will do.

"We get to come out and sweat for a living and play a game that kids play in little league," Walker said. "That’s something every one of us would try to play until we were 50 years old if it would pay the bills.

"This is great. Independent baseball is awesome. It gives guys who may have gotten a raw deal in affiliated ball a chance to compete and be around 5,000 fans. It gives us a chance to live kind of a big league experience. Especially in Winnipeg. They make you feel like big leaguers up there. It’s such a blessing. I wouldn’t play anywhere else."

— — —

It’s 6:30 a.m. when the Goldeyes’ bus pulls into the parking lot at Shaw Park on a holiday Monday morning. The streets are deserted. Dawn has broken.

The road trip has been a wash: three wins, three losses. In the end, they are no further ahead in the wild-card race, but their pennant hopes are growing dim.

One by one, dead-tired ball players step out, still half asleep. There are more red eyes than Goldeyes.

Not a word is spoken as the gaggle drags their gear into the clubhouse. Only one car is waiting in the parking lot. It’s there to pick up pitcher Dexter Carter, who just the night before — before the Goldeyes even left Sioux City — was told by Forney that he’d been traded to the Gary RailCats.

Arrive in Sioux City as a Fish, leave as a Cat.

"I don’t really like to do it that way, but sometimes you don’t have a choice," says a bleary-eyed Forney. "I wouldn’t have done anything if they were doing their business. You can’t stay .500 in a playoff race."

So it goes in the minors. You can chase your dreams. You can chase the girls who serve you chicken wings. You can chase the night.

You can chase the devil or the Saints.

Either way, the game moves on, even if you don’t.

"I remember hearing once that it’s hard when you love the game more than the game loves you," Ace Walker says. "That might have been in a movie. But it’s true."

Then the pitcher smiles.

"But when the game loves you back," Walker says, "it’s a beautiful thing."

Kiss me, baseball.

One more time.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, August 11, 2012 8:23 AM CDT: adds photos

Updated on Saturday, August 11, 2012 6:45 PM CDT: fixes typos