‘Our brains were not actually designed to work that way’: How online learning harms kids’ well-being and what parents can do to help

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/01/2022 (1434 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As kids in Ontario prepare to return class next week, parents and experts worry about the effects remote learning has had over the past 18 months and what a future pivot back to online could mean for kids’ well-being.

“Our brains were not actually designed to work that way, to learn things through two-dimensional screens for hours on end,” said Marjorie Robb, psychiatrist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa.

Online learning can reduce kids’ attention spans, promote multi-tasking (which our brains aren’t designed to do) and create challenges with self-regulation, Robb said.

But the biggest challenge with virtual learning is less about what it is and more about what it isn’t: that is, a dynamic environment in which kids can build and navigate relationships, learn through their five senses and participate in extracurricular activities.

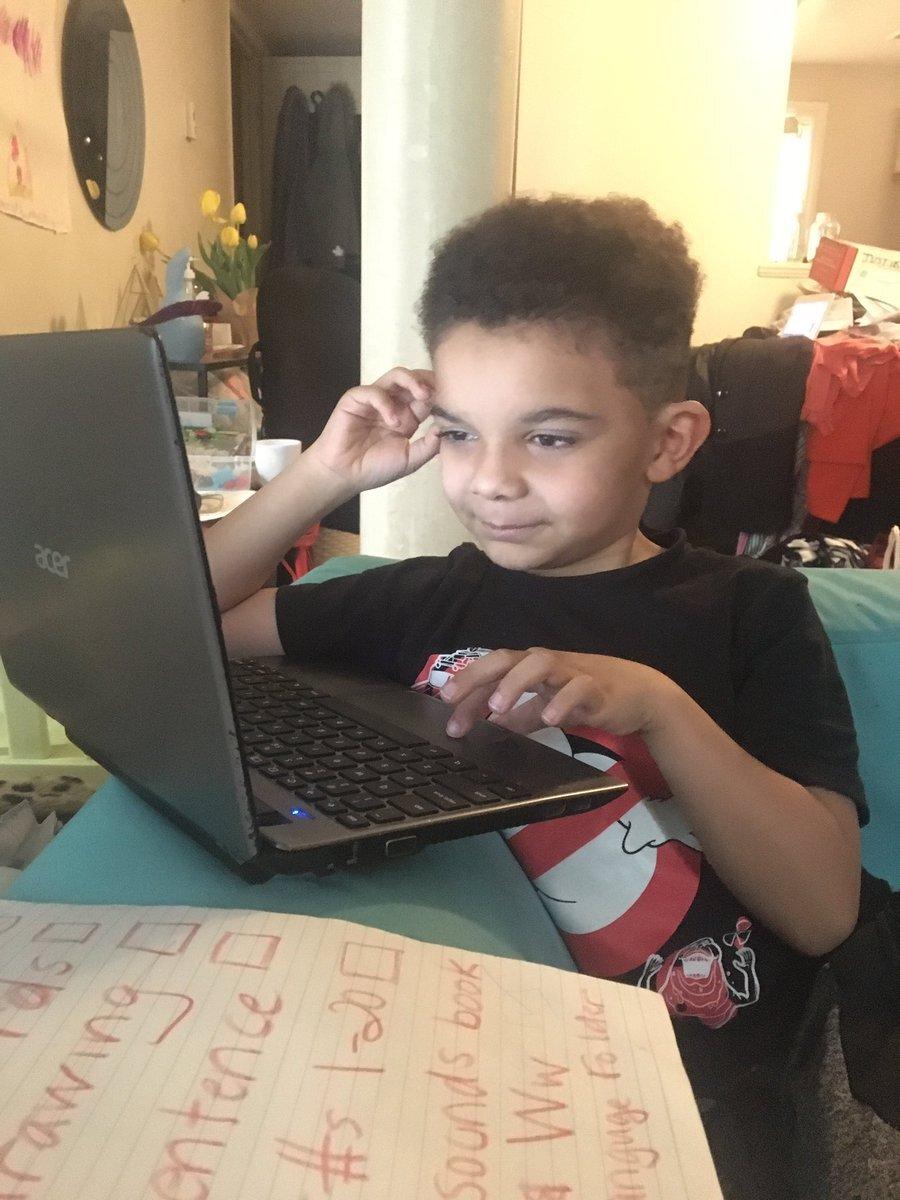

Andrea Moffat says her six-year-old son, Justice, has been struggling to navigate school on a screen and she worries he’s missing out on the social skills that come from being in a physical environment, like learning how to resolve conflict.

With virtual learning, a teacher can’t quietly pull a student aside to ask them what’s wrong, so checking in often means singling them out in front of the class — something that can be particularly challenging for the little ones, Moffat said. She gave an example of this happening when Justice wasn’t participating in virtual gym class and his teacher called him out.

“For some kids, the way that the camera focuses on them, that singling out can be a lot, especially for the little kids,” she said. “He’s only six.”

“The skills for dealing with a bunch of people in two dimensions on a screen are not the same as the skills that you develop by being with real people in real time,” Robb said. Particularly for younger kids who have spent more of their lives online, there can be a “deficit” in social skills like reading body language and learning the “give and take” of interpersonal relationships.

While experts say some students with good technology who suffer from social pressures at school may prefer virtual learning, largely it’s hurting kids’ mental health.

In July, researchers at Sick Kids Hospital surveyed more than 2,200 school-age children (ages six to 18) and found the more time students spent online learning, the more symptoms of depression and anxiety they experienced.

As much as teachers try to make virtual school engaging, kids are missing out on positive experiences that come from being there in person, said Catherine Birken, a Sick Kids pediatrician and author of the study.

“Schools are not just places for learning, they’re also places for social and emotional development,” she said. “When you take that away from children then you’re leaving families with not a lot of options.”

On the first day back after winter, Moffat said Justice was eager to tell his friends about his Christmas and show them his cats, but “the online environment doesn’t allow for that.”

For Brampton father Jagdeep Mann, it’s not only about the extra screen time during school hours, but the challenge of pulling his kids away from screens during breaks and after school, when they’d usually be running around at recess or practising with their sports teams. His son Himmit, 12, plays basketball, and his daughters Harsun, nine, and Dharus, seven, enjoy gymnastics, soccer and swimming.

“As parents, we’re already trying to keep our kids off the screen in normal times,” Mann said. He and his wife work full-time, so they can’t take their kids out to play at lunch or between classes.

The Sick Kids study also found that increased time on screens outside of school — watching TV, surfing the web and playing video games — was associated with more irritability, hyperactivity, inattention, depression and anxiety among youth.

“When you remove all other activities and opportunities from children, then you’re going to see — as we’ve seen — that screen time is going to just explode,” Birken said.

Since returning to in-person school this fall, Mann said his kids have been coming home “bubbly and happy.” It’s a marked difference from last year when months of online learning left them feeling exhausted.

“They just weren’t having fun,” he said. “For kids at that age, school is fun. They go there to interact with their friends. When you’re not having fun during the day, it impacts your mood. It impacts your daily kind of spirit that you have, enthusiasm.”

Robb says scheduling regular breaks, spending time outside, exercising and socializing — even if it’s just with members of the household — can help mitigate the mental health effects of online school.

Birken recommends parents try to encourage more interactive screen time (like online workouts) and develop screen-free times, like during meals and before bed.

However, she said it’s “problematic” to focus mitigation strategies on working parents in a pandemic, and the onus should be on decision-makers to make sports and recreation accessible to children when schools are closed.

Lex Harvey is a Toronto-based newsletter producer for the Star and author of the First Up newsletter. Follow her on Twitter: @lexharvs