How do you teach children about residential schools? Mix history with kindness

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/09/2021 (1534 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On the Piikani Nation reserve in Alberta, Crystal Good Rider grew up under strict instruction to always take care of her teeth.

For years, she found this insistence from her mother confusing in its intensity. Only after becoming old enough to hear the stories of her mother’s childhood in the residential school system did she finally understand.

“They took out all my mother’s teeth at 12 years old,” said Good Rider. “She walked around the residential school for six months without teeth. All because she complained about a toothache.”

Now the assistant principal at Fish Creek elementary school in Calgary, Good Rider has to grapple with the same question her mother must have had when raising her: How do you teach children about residential schools? How do you teach children about terrible things that happened to children, when even adults buckle under the weight of the truth?

What Good Rider and educators around the country told the Star they realized is that you must start early, be consistent, and foster the notion that empathy, kindness and inclusivity are what’s needed to prevent horrific acts from being repeated.

Lesson plans dealing with residential schools proliferated in 2013 with the creation of Orange Shirt Day and were spurred again when the remains of 215 children were discovered at a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

On Wednesday, the Ministry of Education announced a plan to expand First Nation, Métis and Inuit content and learning in the elementary curriculum. Currently, Ontario’s curriculum includes mandatory Indigenous-focused learning in all grades but 1 and 3. Those gaps would be filled starting in September 2023.

The NDP critic for Indigenous and treaty relations, Sol Mamakwa, said it is “sad that these additions to our kids’ education won’t be in place until 2023 at the earliest,” adding that this process could have been expedited if Ontario had not scrapped an Indigenous curriculum writing program in 2018.

Good Rider said when teaching elementary school students about residential schools, lessons should begin by simply imparting the understanding that residential schools were generally not good places. The learning process continues and grows more complex as the students do.

Bojana Dautbegovic-Krienke teaches pre-kindergarten at Mayfair Community School in Saskatoon. That’s when her students, age 3 and 4, learn about residential schools for the first time.

“Orange Shirt Day begins the conversation we have all school year long,” said Dautbegovic-Krienke. “We sit together in a sharing circle and start with the story of Phyllis Webstad. I explain to them that she lived at home with her family, and she felt so much love there, just like we feel from our families.”

Dautbegovic-Krienke then introduces the concept of loss, of being uprooted from everything you’ve known and of the indignity of not being able to keep even the shirt on your back.

“I have all the students bring pictures of their families and items from home,” she said. “We talk about how we have those items at school because they make us feel better, and we know our families are coming back for us at the end of the day. Phyllis couldn’t see her grandma anymore after she went to school. She couldn’t speak her language. They took away her shirt.

“We talk about that, and how sad that would make the children if it happened to them. Then I wrap it up, because I don’t want them to start crying.”

This week, Dautbegovic-Krienke and fellow early childhood educators at the school, Kelly Vickaryous and Heather Mceachern, had students take white T-shirts and paint them orange, symbolically gifting back to Phyllis Webstad her stolen shirt.

Those shirts will hang in the windows of the classroom all year, a catalyst for conversations Dautbegovic-Krienke hopes will persist into her students’ adult lives.

“While we continue to have those hard conversations about residential schools, what they meant and how the children in them felt, we also talk about how we can do better,” she said. “We ask the children how schools can show kindness, and how we can show kindness to each other. We asked each of them to write down one thing they can do that shows kindness. Kindness is the antidote.”

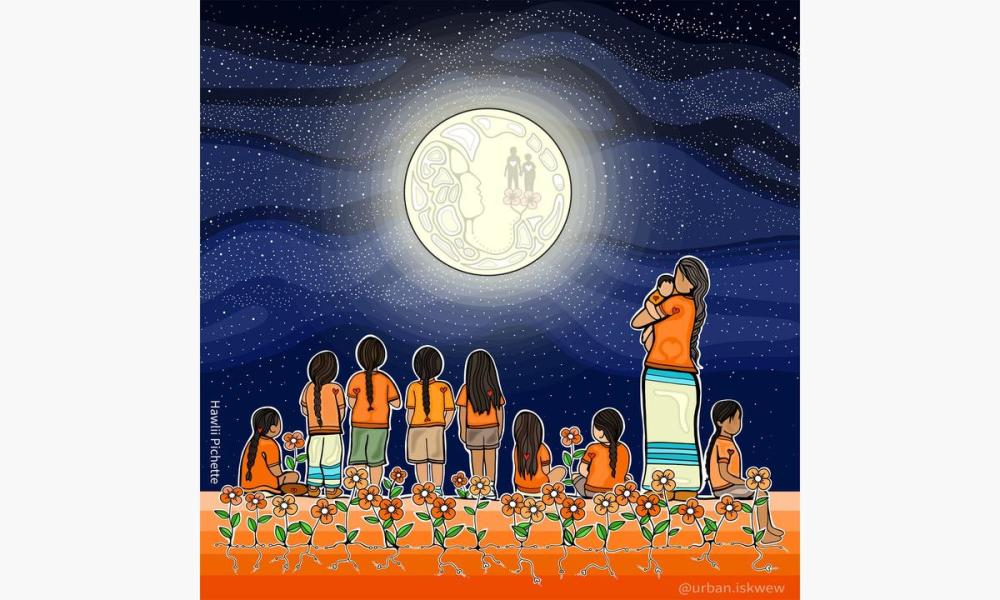

Hawlii Pichette, an Indigenous artist from London, Ont., has been working overtime for weeks to create a series of free colouring pages in advance of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on Thursday. Since she began last year, classrooms around the world have used her art, depicting Indigenous motifs and imagery, to help teach about residential schools.

Pichette’s piece this year depicts nine children and a mother gazing up at the silhouette of two more children holding hands in the moonlit sky. Underneath them are the words “Every Child Matters,” from which flowers are growing.

“The flowers coming out of the words represent the buried children found at residential schools,” said Pichette. “It represents them being visible now. The children looking up at the moon represent the here-and-now, it’s about how children are learning about this, how much empathy they feel.

“The two children in the moon are a way of saying that we remember and honour the victims of residential schools. And that they are together again now — a lot of times siblings got separated by residential schools.”

Monica Sass, a Grade 4 and 5 teacher at Victoria Public School in London, Ont., uses Pichette’s art as a way for students to reflect on the history they’re learning.

“They get to extend their thinking and learning through creative expression,” she said. “Hawlii’s art strikes an intimate chord with me and the students. The images are vibrant, they’re alive and kids are drawn to them. They like to see children, people like them, reflected in their learning, and the fact the children are facing away from the viewer lets kids see themselves in their place.”

After giving her students Pichette’s pages Wednesday, Sass asked how they felt, and what came to mind as they coloured.

“We may have different traits, but we are all people who need the same things,” said her student, Levi.

“It makes me think of the people who are honouring the children who didn’t make it home,” said another student, Abbi.

“A whole bunch of Indigenous people with one white person joining them. Just because I’m different, doesn’t mean we’re different, we’re actually the same,” said Ethan.

Lisa King is an Indigenous education consultant with the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board. She has led in-class programs and after-school workshops with students from kindergarten to Grade 12 for the past five years.

King echoed other educators in saying lessons on residential schools must be capped by lessons on kindness.

“When we look at the culture of the communities that were faced by these schools, their systems, their whole way of life was built on kindness, communal living and making sure everybody had what they needed,” she said. “That was stripped away at residential schools. Turning back to that and looking at the fact that being kind is something that we should be doing every single day is so important.”

King said working in her role is rewarding, and challenging. It’s difficult, she said, to work a job where “everything refers back to your personal life,” the issues that “affected your ancestors, that are going to affect your children and grandchildren, that affect you on a daily basis.”

It is paramount then that celebrations of the richness of Indigenous history be married into lessons of systemic abuse.

“Residential schools, missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, not having clean drinking water — all of those issues come up all the time,” said King. “We need to balance them with the beauty of the culture, the beauty of the teachings.”

Good Rider said her mother, and other survivors, are glad to know their stories are now being told.

“When the Kamloops situation happened, I came home from work and my mother asked me if we talked about it at school,” said Good Rider, who indeed had. “She said, ‘I’m so happy that people are starting to know what happened to us.’ ”

Ben Cohen is a Toronto-based staff reporter for the Star. Follow him on Twitter: @bcohenn