If you rebuild it… It will take a lot more than the return of office workers to get downtown back on its feet

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/12/2022 (1075 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The plastic is still on the newly purchased couch.

The walls are bare, save for a few empty wooden shelves.

For Chris Watchorn, 288 Colony St. is a blank slate — a prime piece of real estate near the University of Winnipeg, empty but full of promise.

“Hopefully this place becomes more of a community thing as much as it becomes a retail thing,” he says, standing in the soon-to-be men’s apparel shop in early December. Beyond its doors, across the hall, a few other ground floor units sit vacant.

Opening his new business — Hobby•ism — in the downtown area was critical for Watchorn.

“You go to a city like Toronto or Montreal, and you don’t even think twice — downtown is where you head,” he says. “Ours will never get there unless people are willing to put in the time and effort and money.”

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Chris Watchorn (left), co-founder of Hobby•ism, with one of his business partner’s, Daniel Basanes.

It’s impossible to miss the for-lease signs when walking along downtown streets. They’re nearly as omnipresent as surface lots.

Downtown office vacancy rates had been trending upward throughout 2021 and have now hit an “all-time high,” says Paul Kornelsen, vice-president and managing director of the Winnipeg branch for CBRE, which tracks commercial real estate numbers.

Oklahoma City’s path

Mick Cornett has a clear message: your city gets its identity from its core.

It’s what the former Oklahoma City mayor told attendees of Winnipeg’s first State of the Downtown convention last September. Revitalization requires more than bringing back office workers, he noted.

“When you don’t have people living there, and you don’t have visitors, what happens is, you don’t have retail (and) you don’t have restaurants,” Cornett told the Free Press in December.

Mick Cornett has a clear message: your city gets its identity from its core.

It’s what the former Oklahoma City mayor told attendees of Winnipeg’s first State of the Downtown convention last September. Revitalization requires more than bringing back office workers, he noted.

“When you don’t have people living there, and you don’t have visitors, what happens is, you don’t have retail (and) you don’t have restaurants,” Cornett told the Free Press in December.

In the ’90s, Oklahoma City was basically a dead zone. In hopes of drawing traffic after 5 p.m., the city built a canal through an old warehouse district, creating an entertainment sector, and changed one-way streets to two-ways. Developers built a downtown library, a sports arena, and a performing arts centre.

The city used tax increment financing and paid for infrastructure, in part, by implementing a temporary one per cent sales tax.

“I think people are more likely to vote for something if it’s not permanent,” Cornett said.

Affordability, walkability and clean air are key to attracting downtown residents, especially young professionals, Cornett said.

Building up the downtown requires creating key amenities, like barbershops and laundromats, should more people live in the core, he added.

Having a sports franchise is “extremely important” because it associates your city with bigger metros, Cornett said.

— Gabrielle Piché

As of the fall, 16.1 per cent — or roughly 1.6 million square feet — of Winnipeg’s downtown office space was empty, up from 12.3 per cent two years earlier. Nationally, the average downtown office vacancy rate was 16.9 per cent this fall. In Calgary, it’s a whopping 32.9 per cent.

Remote and hybrid work have played a role in the vacancy rate, Kornelsen says, but the upward trend began prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Executives were already reconfiguring offices, vying for open concepts that required less square footage per employee.

“As more space becomes vacant, it’s not likely to get absorbed by the current, existing office market (in Winnipeg),” Kornelsen says. “We need to think about what to do with the inventory.”

But converting offices for other uses isn’t as easy as removing the desks.

It’s expensive and often not feasible for developers because the return on investment isn’t there, Kornelsen says.

Still, it can be done. Now an apartment block, 433 Main St. used to be a passport service building. Developers flipped Carlton Street offices to residential properties, he says.

Dayna Spiring, Economic Development Winnipeg’s CEO, is also cautious about converting buildings, though for different reasons. She is hopeful demand for office space will resume.

“I think the pendulum has swung,” she says.

Working from home was the only viable option for many early in the pandemic, but it’s been almost three years; people need interaction, she says.

“I think you can maintain (corporate) culture for a period of time, but I don’t think that you can build it,” Spiring says. “I think you need people in office space to be able to do that.”

Flexibility — a mix of home and office work — will likely become the norm, Spiring says. As of September, 64 per cent of downtown office workers had returned to their desks at least part-time, according to a Probe Research poll, and of those, 41 per cent had returned full-time.

“You need to be able to address the flexibility in how and where employees work, or you will not win the battle for talent,” says Loren Remillard, president of the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce.

At the end of November, his organization unveiled its new headquarters — mid-construction — at the corner of Portage and Main. Once it’s complete, the chamber’s employees will share space with CentrePort Canada and World Trade Centre Winnipeg.

Chamber employees will come in at least twice weekly. Renderings show couches and a common area for workers.

“This model allows us to be able to grow without necessarily having to take on more physical space and… (the) cost associated with that,” Remillard says.

Although it’s not the case for everyone, “the laptop is your office today,” he continues. “As long as there’s a place to sit down, put your coffee and collaborate and do work — that’s kind of (what) our office design is built to do.”

Natassia Brazeau, co-owner of Northlore, gazes out at a street devoid of pedestrians in the middle of a cool November weekday. Brazeau had recently celebrated the one-year anniversary of her body care shop’s Exchange District storefront opening.

Although the 75 Albert St. business isn’t empty, it’s often quiet. Without online sales to compensate for the lack of foot traffic, she fears she wouldn’t have made it.

“I would be very nervous if it was just the shop,” Brazeau says.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES Natassia Bezoplenko-Brazeau at her Northlore store, a body care shop which makes many of its own products and tries to source as locally as possible.

Nearly three years of pandemic-induced economic convulsions have taken their toll on downtown businesses.

Since March of 2020, 104 have closed while 70 have opened. In this year alone, twice as many have shuttered compared to opened — 45 to 20 — according to Downtown Winnipeg BIZ data.

Pre-pandemic, the trend was reversed — double the number of businesses opened than closed annually.

Steps away from Northlore, Rod Sasaki has run Warehouse Artworks at 222 McDermot Ave. since 1988.

“Maybe a year or two before the pandemic, that’s when I saw the area as being the strongest I’d ever seen it,” Sasaki says. “It’s just not what it used to be.”

He’s one of the lucky ones. He has long-time clients who keep returning and Warehouse Artworks is a destination shop.

There are numerous issues that need to be addressed, he says, adding the protected bike lanes along McDermot have hindered business. A lack of foot traffic from fewer office workers and a perception of rampant crime downtown haven’t helped, either.

“You’re going to see a lot of for-lease signs (here), which is not… good,” Sasaki says. “You need more people downtown.”

“It’s a very critical time for downtown,” says Angela Mathieson, president of CentreVenture.

Downtown has been “recovering” for decades with development in the city’s core hitting a “pretty high watermark” in 2017-18, she says.

In 2017, the private sector invested $435.1 million into new projects and significant conversions downtown, including True North Square, a public plaza and mixed-use high-rise development.

From the eyes of business owners

There’s no silver bullet to fixing the lack of foot traffic downtown. However, entrepreneurs have ideas. The Free Press gathered suggestions from a handful of them.

Natassia Brazeau, co-owner of Northlore, wants a livelier Exchange District. For this, you need more residents and amenities, like a grocery store, and better maintenance of outdoor spaces, including more frequent sidewalk clearing.

Most of all, she wants help for people living on the street.

“I personally believe that (a lack of) social supports for people would be the biggest barrier right now,” Brazeau said, calling for public washrooms and “things that give people dignity.”

There’s no silver bullet to fixing the lack of foot traffic downtown. However, entrepreneurs have ideas. The Free Press gathered suggestions from a handful of them.

Natassia Brazeau, co-owner of Northlore, wants a livelier Exchange District. For this, you need more residents and amenities, like a grocery store, and better maintenance of outdoor spaces, including more frequent sidewalk clearing.

Most of all, she wants help for people living on the street.

“I personally believe that (a lack of) social supports for people would be the biggest barrier right now,” Brazeau said, calling for public washrooms and “things that give people dignity.”

“The reality is, from my perspective living and working in the neighbourhood, not that it’s unsafe, just that there are a lot of people that are struggling,” she said.

Her neighbour Rod Sasaki envisions the removal of protected bike lanes from the front of Warehouse Artworks. He said they’re barely used in the winter, and have cost the area valuable parking spots.

“There’s definitely a lot (of) people with disabilities… trying to get around (and) not being able to park close,” Sasaki said.

Dade Williams, manager of Aluminum Sound, would like to see a bigger security presence and seconds the call for a grocery store.

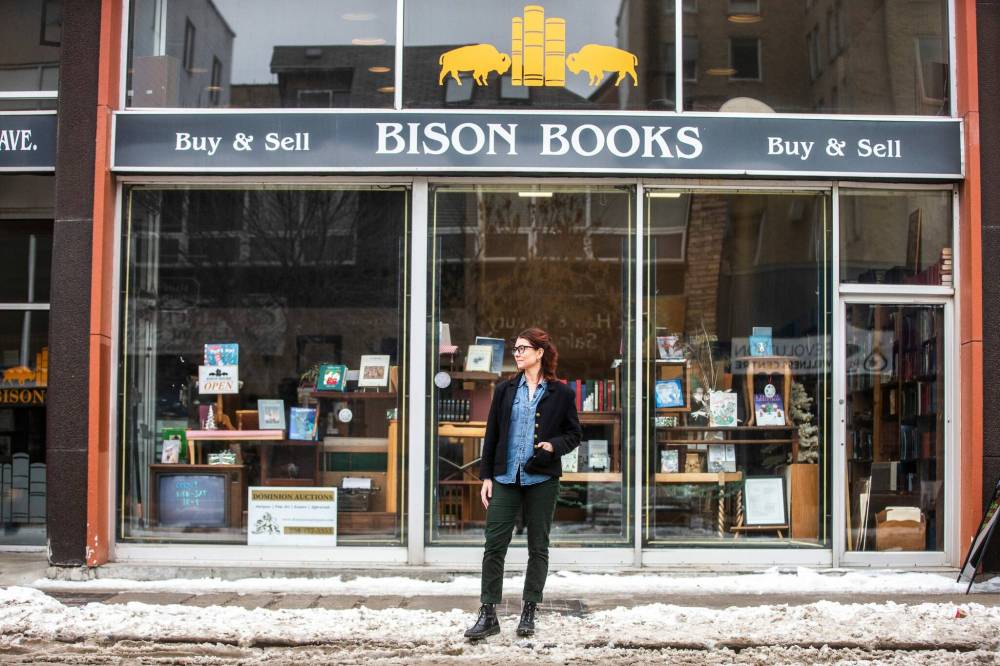

“We need more people working downtown, more people living downtown, more people shopping downtown,” said Aimee Peake, owner of Bison Books.

Having a network of businesses helps draw customers, said Peake, who gave the example of a restaurant, bookstore and coffee shop in the same block.

“I’d love to see the supports that we are being offered now continued so that we can stay here and continue to invest our time,” Peake said, referring to recovery-targeted programs.

Dominika Dratwa moved her Verde Plant Design business from Graham Avenue to Osborne Village before the pandemic, but has found that area is also facing challenges, she said.

While downtown has a feeling of emptiness, “Osborne is like a highway with a bunch of small shops on it,” she said. “Nobody wants to walk on a highway.”

“We’ve considered moving out of the Village and going straight south, but we’re here for now.”

Both locations require “creative and radical change” that go further than renting out spaces to businesses, she said.

— Gabrielle Piché

In 2018, investment was $380 million — $265.6 million from the private sector, and another $114.4 million from the public and non-profit side.

“I think prior to the pandemic, people were feeling very, very confident… because things seemed to be going so well,” Mathieson says. “At CentreVenture… we were concerned.”

The organization, which began in 1999 to assist private sector investment downtown, was tracking a decline in investment in 2019.

Then, the pandemic arrived and it turned to 2020. Some projects were “past the point of no return,” Mathieson says — so, the private sector spent $108 million on major development that year, and the public and non-profit sector spent another $150 million. There were five major developments in 2020.

The numbers dropped in 2021 — a collective $37.4 million was spent, the lowest investment since 2009.

“We are now really starting, in the development industry… to feel the real impact of the pandemic,” Mathieson says.

This year has elicited two major downtown development projects: both from the private sector, both on land purchased pre-pandemic and both mixed use — on Donald Street and Bannatyne Avenue. They cost $84 million combined.

Inflation and high interest rates are preventing companies from building, Mathieson says.

“I think the city needs to look at the next couple of years and determine, ‘Where do we want that trend line to go?’” she says. “To some degree, government attention to the downtown really drives private investment… it breeds a sense of optimism.”

Dade Williams wears his headphones while walking to work on Graham Avenue.

“I keep them on, but they’re not necessarily on, so you can hear the surrounding area,” Williams says. “(People) won’t approach you or talk to you, or you have a reason to just keep on.”

His guard is up — and he assumes it’s the same for others trekking in the area, near the corner of Graham Avenue and Vaughan Street.

“You’re at Polo (Park shopping mall), you’re just browsing. If you’re at Corydon, you’re just looking around,” Williams said. “If you’re downtown, you’re on your guard the whole time… you’re not browsing.”

Crime, perceived crime and people experiencing homelessness are dissuading customers, says Williams, Aluminum Sound’s manager. He’s had to call police several times.

“Nobody’s going to come down here if it’s not safe, and businesses won’t come down here,” Williams says.

As of August, non-violent crime jumped 122.3 per cent year-over-year in South Portage, where Aluminum Sound resides, according to the Winnipeg Police Service’s CrimeMaps.

There were 1,354 incidents during 2022’s first eight months, compared to 2021’s 609 through the same time period. Both 2020 and 2019’s non-violent counts are closer to this year’s — 1,266 and 1,557, respectively.

Violent crime has also increased in the South Portage area: police counted 359 incidences in the zone as of August, the most for that time period in the past five years.

More foot traffic is needed for a vibrant and safer downtown, says Aimee Peake, owner of Bison Books. She’s just agreed to continue leasing 424 Graham Ave. for three years.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS More foot traffic is needed for a vibrant and safer downtown, says Aimee Peake, owner of Bison Books.

“Everyone has to do their part,” she says. “You can come downtown and run to the dentist and then go home, and then talk about how it didn’t seem very vibrant. Or, you can go to the dentist and (then) go to one of the stores and support them.”

There are several vacancies near Bison Books — about 30 per cent of downtown ground floor business space is vacant — but still, Peake is hopeful.

Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham said in November the city, along with the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ and other stakeholders, will transform Graham Avenue. It’s unclear what the strip will become.

“Having a pub in the area, or a brewery… more things that bring life (would be nice),” Peake says. “More independent small businesses — if some can cluster, it can be a bit of a pedestrian experience.”

Williams is hopeful too. He’s anticipating positive change once the Southern Chiefs’ Organization converts the former Hudson’s Bay building, steps from his shop.

The new facility, to be called Wehwehneh Bahgahkinahgohn, is set to include 300 affordable housing units, assisted living for elders, a daycare, health and healing centre, museum, rooftop garden and Paddlewheel restaurant.

Both the provincial and federal governments are spending millions on the conversion.

Earlier this year, the provincial and federal governments gave a total of $5 million to the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ’s Building Business grant program. Downtown companies renovating or expanding, and organizations moving to the core, can apply for funding.

More than 150 businesses — including 38 not yet open — have applied, Downtown Winnipeg BIZ’s CEO Kate Fenske says.

“It’s good news. It really shows that the support is still needed for business downtown, but it also shows the interest,” she says.

The BIZ is spending $300,000 of the funding on a marketing campaign to, in part, re-attract office workers. It’s budgeting $1.8 million for business development, advocacy and research next year.

Still, Fenske doesn’t expect office workers to return full time.

“We want to make (downtown) a place where people come to connect, to experience… to explore,” she says.

“We want to make (downtown) a place where people come to connect, to experience… to explore.”–Downtown Winnipeg BIZ’s CEO Kate Fenske

The City of Winnipeg has introduced tax increment financing for affordable housing and downtown development.

“We want to make sure… in this economic climate where there’s inflationary costs… that the city’s doing all we can from a policy perspective to make sure that we’re still a wonderful place to invest in,” says Coun. Sherri Rollins (Fort Rouge—East Fort Garry), who chairs Winnipeg’s property and development committee.

The committee passed a motion in November directing city staff to explore office-to-residential conversions and advise appropriate changes to zoning bylaws.

Artists “clamouring for space” for rehearsal chambers and studios are eager to play a role, says Thom Sparling, Creative Manitoba’s executive director, but he gets frustrated when he sees vacant buildings.

The problem is twofold — the buildings aren’t up to code and arts groups can’t afford the rent landlords would need to charge if they renovated.

In Toronto, billboard renters pay a tax that gets funneled into the city’s arts community. Such a levy could generate dollars for fixing old buildings in Winnipeg, he says.

“There needs to be some kind of public intervention,” Sparling says.

Meanwhile, back at Hobby•ism, Watchorn offers his vision. Maybe Winnipeggers could buy a shirt at the Colony Street store post-Winnipeg Art Gallery visit. Maybe, if a coffee shop moves nearby, customers will grab drinks after.

“It feels like there’s a lot of opportunity (downtown),” he says. “We just wanted to be part of that narrative.”

gabrielle.piche@winnipegfreepress.com

Gabby is a big fan of people, writing and learning. She graduated from Red River College’s Creative Communications program in the spring of 2020.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.