Two cities, one drug crisis, two different approaches Amid a toxic drug crisis, Winnipeg and Hamilton go in starkly different directions

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/12/2022 (1162 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

‘I’d be dead. I know so’

Hamilton’s toxic drug problem has been met with safe-consumption sites and life-saving lessons survivors and staff hope Manitoba will embrace

HAMILTON — Randy sinks into a wooden chair in the corner of an old church, a hat and sunglasses shielding his eyes from the light, and offers a stark message to Manitoba.

If he lived there, he says, he’d be dead.

This isn’t hyperbole. It’s something Randy knows as fact.

Manitoba does not have a safe consumption site for drug use, unlike his current setting. It’s here, in the church, where staff have saved his life numerous times when he overdosed.

Without them, “I’d be dead. I would be dead. I know so.”

The supervised consumption site is located in a downtown Hamilton Presbyterian church — an historic building also home to occasional filming of the Murdoch Mysteries TV series — just a block from city hall.

Run by Hamilton’s Urban Core Community Health Centre, the Consumption and Treatment Service (CTS) is staffed by health-care professionals, peer support workers and harm-reduction counsellors. It’s open noon to 8 p.m. Monday to Friday, and it’s a space for people who use drugs to pick up clean needles and other supplies, to get referrals for other supports and to consume drugs they bring in.

“The folks who are coming to use the CTS site are responsible citizens,” site manager Nadine Favics says. “They’re choosing to come to be supervised by staff and peers to make sure that they’re OK.”

The CTS was established in 2018, a year after a study by Hamilton’s public health department recommended the city needed at least one, if not more, sites in the city.

The Free Press travelled to Hamilton in November to see how supervised consumption sites work in a city of comparable size to Winnipeg, with a toxic drug crisis that’s just as bad and getting worse.

Supervised consumption sites, also known as safe injection sites or CTS in Ontario, are spaces where people can possess and use their own drugs without fear of being arrested. The sites are supervised by trained staff and health-care professionals who will step in and revive clients showing signs of overdose.

From the outside, the only hint of the services provided within was a laminated sign on a door stating CTS hours of operation. The entrance is at the back of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, wedged between a parking lot and a garden. A gardener confirmed it was indeed the right spot.

The church is just a temporary location for the CTS — when construction is complete on Urban Core’s new health centre just east of downtown, the site will move there.

Inside, it looks like a typical health-care clinic. Masked staff greet clients from behind plexiglass in the reception area, and just beyond is a narrow white-walled room where there are four stations, each with a desk, a chair, clean needles, a yellow sharps-disposal bin, sterile wipes, tissues, a lamp and other clean-drug-use supplies.

Favics says the space is rooted in harm reduction, with staff striving to “meet people where they’re at.” She is acutely aware of the misconceptions people have about safe injection sites and is quick to explain this is lifesaving health care, plain and simple.

“Safe injection is about preventing somebody from dying,” Favics says.

In the reception area, one chair stands out. It’s purple, symbolizing overdose awareness, and on it sits a board filled with names and notes.

Ryan. Lisa. Hailey. Catt. Justin. Darcy. “Ol Man Bobby.” Simba.

“We’ve lost several clients,” says Jess, a CTS harm-reduction counsellor who asked to go by her first name only. “It’s part of the opioid crisis.”

”Safe injection is about preventing somebody from dying.”–Nadine Favics

Still, no one has died at this CTS. In fact, there are no reports of anyone dying at a supervised consumption site anywhere in Canada.

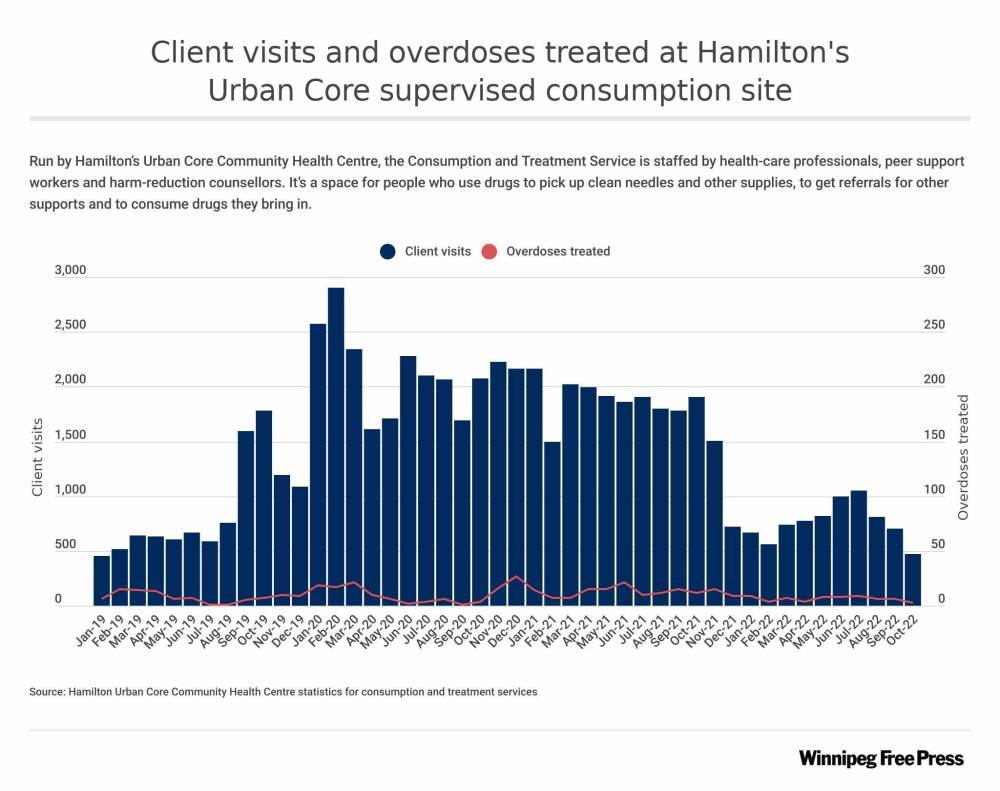

The data show it’s working: of the 20,500 total client visits in 2021, there were just 123 overdoses — all of which were reversed by site staff or emergency responders. Naloxone, oxygen or rescue breathing is used to revive clients experiencing overdose. Of the drugs clients consumed at the site last year, Urban Core’s statistics show fentanyl accounts for half, crystal meth for 31 per cent, and the rest is crack, hydromorphone — a powerful painkilling opioid prescribed by doctors in Hamilton to those with addictions issues — and other drugs.

The site relies on funding from the Ontario provincial government to cover its $1.2-million annual budget, which includes about 11 full-time staff and all operation and administrative costs.

The CTS is more than a location for using drugs, staff say. It’s a place where clients can be connected to mental-health supports, housing, jobs, counselling and treatment. These connections happen because staff develop relationships and build trust with clients — many of whom have felt stigmatized in the mainstream health-care system.

“At the end of the day … if I can connect with even just one person and make them see that they are valued and what they’re worth is, then I’ve done my job,” says Jess, her eyes tearing up. “It’s just providing a safe space for people to come and know that they’re loved.”

She wants to make one thing clear — addiction can happen to anyone.

Clients share stories of living typical lives until a car accident happened, followed by surgeries, followed by prescriptions for opioids for pain management, followed by addiction.

“You and I could know somebody right now affected by it and we may not even know that that person is addicted,” Jess says.

Outside of Atlantic Canada, Manitoba is the only province without a safe injection site — a seemingly little-known fact to those outside our borders.

“I’m very surprised that Winnipeg doesn’t even have one,” Favics says. “I’m not quite understanding (why)… we know that the opioid crisis is very real.”

While it’s difficult to compare drug crises in two cities 2,000 kilometres apart, there are similarities when looking at overdose statistics and accounting for population — Hamilton with approximately 570,000 residents and Winnipeg with 750,000.

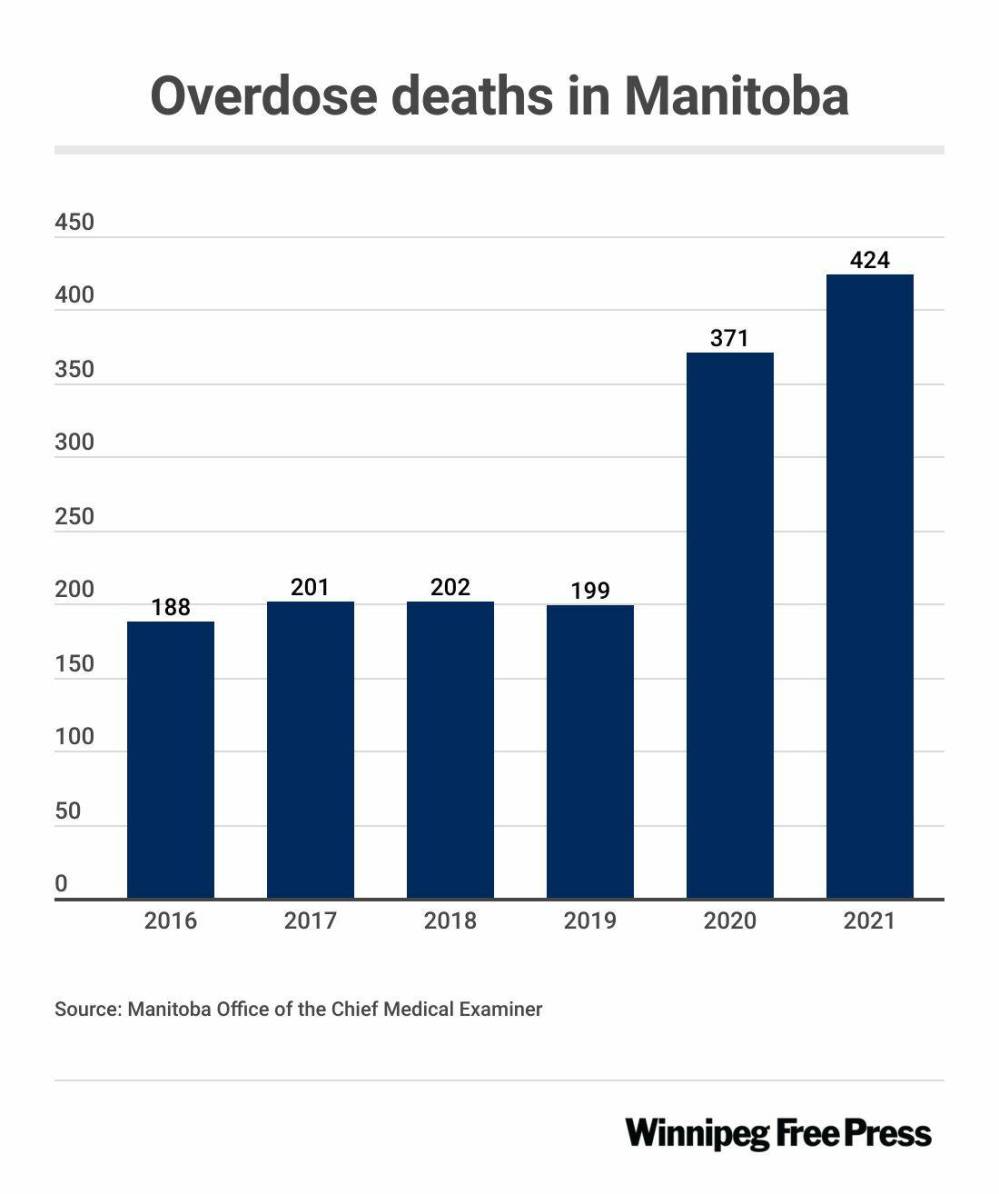

There were 128 opioid-related deaths in Hamilton in 2020 and 271 total overdose deaths in Winnipeg that same year, more than double the 123 deaths in 2016. (The 2020 Winnipeg figure is the most recent from Manitoba’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Opioid-specific data for Winnipeg was not available and Hamilton public health did not have total overdose data available.)

In Manitoba, the Progressive Conservative government has long been lukewarm, and at times staunchly averse, to safe injection sites. The government, with Heather Stefanson as leader, seemed to open the door for the possibility of the sites earlier this year, with Community Wellness Minister Sarah Guillemard saying in April safe consumption sites can work “if they’re used in conjunction with strong core services.”

Last month, the Tories hardened their opposition. The government said it was rejecting the prospect of safe injection sites — after doing subsequent research — and will now focus on a “recovery-oriented system of care.”

Critics lashed out at the province over this stance, saying the decision was based on ideology not evidence. Premier Stefanson and Guillemard specifically came under fire after Stefanson repeatedly referenced non-existent sanctioned supervised consumption sites in California and Guillemard suggested she visited supervised consumption sites in Vancouver, when in fact she never went inside.

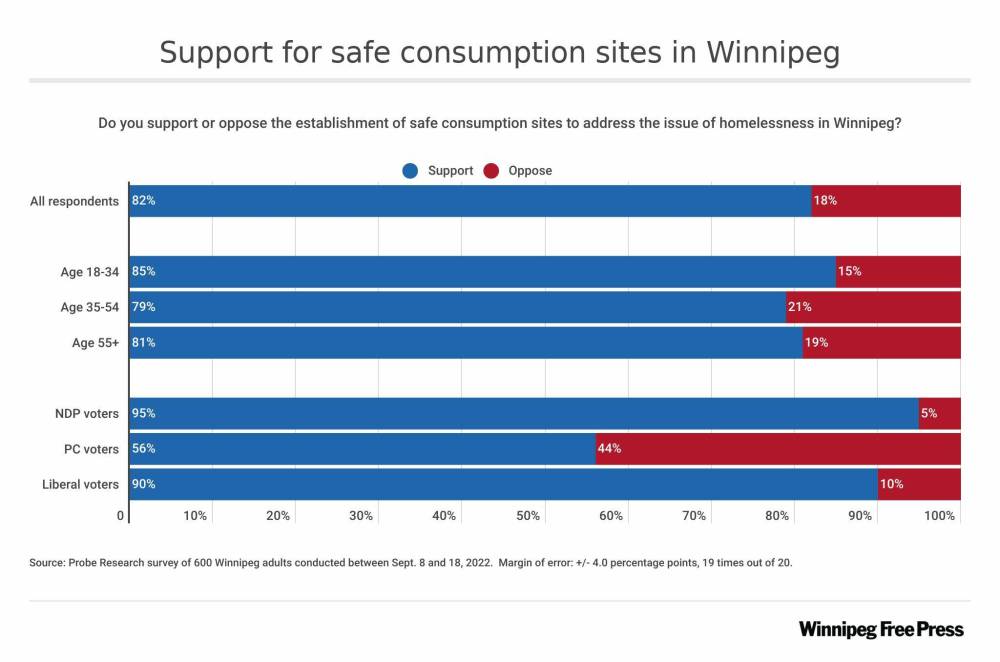

Overwhelmingly, Manitobans disagree with the current government’s approach.

Four years’ worth of polls have indicated two-thirds of Manitoba residents support the life-saving sites. A Probe Research poll conducted in Winnipeg in September showed 81 per cent of respondents said they would support safe consumption sites — with only 18 per cent opposing the idea.

Hamilton’s second iteration of a safe injection site opened in April. It’s called a “safer use drug space,” though it ultimately provides similar supports to the Urban Core CTS.

It operates out of Carole Anne’s Place, a YWCA-run low-barrier, overnight drop-in centre for people who identify as women, and operates in partnership with Keeping Six, a community-based organization that advocates for people who use drugs, and HAMSMaRT, the Hamilton Social Medicine Response Team. It’s funded by the Hamilton Community Foundation and Women 4 Change and it is only the second gender-specific drug consumption space in Canada.

Mary Vaccaro, a YWCA liaison who helped get it running, said before the centre was in place, staff were responding to at least one overdose call a day in and around the building.

“That meant that we would have to call paramedics,” Vaccaro says. “Since opening the space, yes, we have overdoses in here, but we have not had to call the paramedics once.”

More than 130 women have used the site — with many visiting on a regular basis — and there have been 26 cases of drug poisoning, Vaccaro says. Each time, the person was revived by staff and recovered.

They use the term “drug poisoning” because “overdose” doesn’t necessarily capture what’s happening, Vaccaro says.

“The drug supply is so toxic — you might come in and do the same amount each evening, but one evening you go down,” she says. “So you didn’t overdose per se, it’s not like you took more than you always take … you were poisoned. The drug was too strong. It wasn’t what you thought you’d be taking.”

“The drug supply is so toxic… you might come in and do the same amount each evening, but one evening you go down.”–Mary Vaccaro

Inside, the space looks something like a blood donor clinic mixed with a school classroom. There is art on the walls, made by women who use the service, cookies and snacks in drawers, and a thriving green fern named Larry, brought to the site by a client.

It’s important the room feels welcoming, different from traditional health-care environments where people who use drugs may have had bad experiences, Vaccaro says.

There are two stations at which women can consume drugs (inject, ingest or snort — smoking has to happen outside due to air-quality concerns) with the option of a privacy curtain. The same sterile supplies available at the CTS are available here. There are two padded chairs for the women to relax in after they’ve used drugs; they are observed for 20 minutes but invited to stay for longer. The chairs can be folded out into a prone position in case medical intervention is required.

“They’re also just really comfortable,” Vaccaro says.

The site is located just across the street from the church where the Urban Core CTS is temporarily located. On the street outside the YWCA, the scene is lively, with clients, staff and visitors coming and going from the building, and others in tents out on the sidewalk, their belongings piled with them. Staff are focused on meeting people where they’re at, Vaccaro says, and some who spend most of their time outside will come in to use the safer-use space at night.

She wishes all shelters had spaces where people can use drugs out in the open, rather than secretly in bathrooms and stairwells.

“Finding someone on the floor after an overdose where they’re completely blue — you don’t know how long they’ve been out, you don’t know what they used, you don’t even know if it’s an overdose — it’s such an anxiety-provoking feeling,” she says.

Here, things feel “in control.”

“You know what they used, you know when they went down, you have the tools to bring them back,” she says, noting staff have access to oxygen and Naloxone. “It’s never not worked.”

This is technically a temporary site, in existence thanks to an “urgent public health needs site” exemption from Health Canada in response to Hamilton’s toxic drug crisis.

But Vaccaro hopes — and expects — to make the site permanent.

Hamilton’s third site is pending and has been for a few years. It’s hit a few roadblocks — including community pushback and additional government requirements in order to get funding, says Tim McClemont, executive director of The AIDS Network in Hamilton, the group overseeing the project.

Part of the community resistance comes from a place of not understanding, he says.

“Harm reduction often gets confused with encouraging drug use,” McClemont says. “The idea is not promoting drug use, it’s promoting health care and support and to save lives.”

When speaking with concerned citizens in the city’s east end, where the site would be located, he explains the value of harm reduction.

“This is simply a program. I don’t know what people think it is… It’s like a clinic.”–Tim McClemont

People are already using drugs, he says, and supervised consumption sites can save their lives and keep them safe, reducing the risk of blood-borne infections spread through used needles. Having a safe space for drug users also means fewer emergency-responder calls due to overdose, fewer police calls — the site will have their own security and police can’t arrest people for having drugs at safe injection sites — and fewer used needles on the streets.

“There’s always going to be issues, of course. Not everyone is perfect,” he says. “But the idea that (clients) are ‘out of control’ because of drug use… is stigmatizing.”

And McClemont addresses NIMBYism head on.

“So it can’t be ‘in my backyard’ — where does it go? Out in the field somewhere?” he says. “This is simply a program. I don’t know what people think it is… It’s like a clinic.”

Police, the ward city councillor and many community members are in favour of establishing the site, he says. Even though any opening will be months later than he would have liked, McClemont remains optimistic the obstacles will soon be overcome.

Back at the Urban Core CTS, staff ask if two regular clients, Randy and Christine, want to speak with the Free Press. Both were shocked when they learn Manitoba has no supervised consumption sites. They are eager to share their experience of using the site.

“It’s not like I’m home, but it’s the closest thing — I can relax like I am,” Randy says, settling into a chair in a large echoing wood-paneled room next to the CTS. “I’m just comfortable.”

On the street, Randy says he’s always on alert, afraid someone’s going to rob him, hurt him or arrest him, especially when he’s using drugs.

Inside the site, people look out for him.

“It’s a safe space, you know what I mean?” adds Christine, bundled up in layers. She lives on the street, often sleeping at Carole Anne’s Place.

“We’re going to do the drugs regardless,” she says. “It’s just they provide safe supplies to use them, a safe space to use them.”

While Christine talks, Randy nods off. She nudges him. He hasn’t slept in days, he explains — he’s not experiencing a drug overdose. Still, staff keep a watchful eye on him, also nudging him when he drifts off again.

Both Randy and Christine say CTS staff offer supports and are not judgmental. Staff also aren’t encouraging drug use — they’re just meeting people where they’re at, they say.

For instance, Randy says no one’s ever told him what he can and can’t use, but if staff are worried he might overdose, they might suggest he split up his doses.

“They’ll be ready if you don’t,” he says.

“We’re going to do the drugs regardless… It’s just they provide safe supplies to use them, a safe space to use them.”–Christine

The Urban Core website refers to CTS as a “lifeguard station.” It’s a fitting description.

“I know people who wouldn’t be here anymore if this place wasn’t here,” Christine says. She’s seen staff revive Randy “numerous times,” she says.

Outside the site, she’s helped revive people too. Sometimes people don’t respond well — they can be angry when their high has been interrupted, or in denial that they needed help, she says. And even if people are using with others, which is safer than using alone, there are still risks.

Just a few weeks ago, Christine’s friend overdosed. Even surrounded by a group of people, no one noticed until it was “way too late,” she says.

Her friend died.

“It never gets easier,” she says. “It’s hard to be in this scene and not witness a drug overdose.”

Randy and Christine want to spread the word about the good the CTS has done — for them, and the Hamilton community at large.

They hope Manitoba listens.

‘They are getting it wrong. And it is killing our children.”

Advocates say Manitoba needs to put evidence-based research before ideology when it comes to adoption of life-saving safe consumption site model

One kilometre from Manitoba’s legislature, under the watchful eye of the Golden Boy, is a bathroom that doubles as a safer injection site.

It’s “safer” because staff at Nine Circles Community Health Centre support people who use drugs by handing out harm-reduction supplies such as clean needles and — recognizing people may use drugs in their space — keep a close eye on the bathroom.

Clients know that after a 10-minute time limit is up, an unanswered knock on the door will be followed by a concerned staff member opening the door, ready to respond to an overdose.

“Instead of pretending that it’s not happening, we recognize that it might be happening,” said Kim Bailey, director of prevention, testing and wellness at Nine Circles, adding that staff strive to give clients as much privacy and dignity as possible, while still ensuring they’re safe.

“It’s not an ideal scenario in any way. It’s not what we would recommend as a practice in terms of providing safe spaces for people to use substances.”

No one in the legislature has signed off on the bathroom, but they’ve also not signed off on any supervised consumption sites in Winnipeg — or in Manitoba for that matter.

So there the bathroom sits; stark, clean and supervised.

As part of a Free Press’s series examining challenges facing Winnipeg’s downtown, this story looks at harm reduction and supports available to those who use drugs in our city in the absence of supervised consumption sites. The “safer bathroom” is just one example of the lengths harm-reduction advocates are going to, in order to keep those with addictions issues safe and alive.

Still, the advocates question why they need to resort to these makeshift practices and why the province is ignoring their pleas for the supervised sites amid a drug crisis tightening its grip on the city’s most vulnerable.

“I believe that (the Tories) are beholden to an extreme right-wing approach to dealing with addictions and drug use,” said Thomas Linner, provincial director of the Manitoba Health Coalition, a non-partisan non-profit that advocates for better public health policy.

“This government is uniquely hostile to harm-reduction services.”

Linner and other advocates say the Stefanson government’s opposition is rooted in ideology, rather than in evidence that overwhelmingly highlights the benefits of such sites.

Among other things, Linner said supervised consumption sites can:

- limit the number of discarded used needles in communities;

- cut down on calls to paramedics and emergency room visits;

- connect people who use drugs with wrap-around supports including housing, counselling and treatment options;

- reduce the risk of HIV and other blood-borne diseases; and

- most importantly — keep people alive.

Outside of Atlantic Canada, Manitoba is the only province with no safe injection sites.

In November, the Stefanson government said it was rejecting the sites in favour of a “recovery-oriented system of care,” including treatment, naloxone kit distribution and Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine (RAAM) clinics.

Premier Heather Stefanson has insisted she’s taking an “evidence-based approach” but critics reject that argument. Stefanson came under fire after referencing increases in crime at sanctioned safe injection sites in California, despite no such sites existing there. There were calls for Community Wellness Minister Sarah Guillemard’s resignation after she suggested she visited supervised consumption sites in Vancouver, despite never going inside.

“The evidence cannot point in the direction they want it to point, so they are reduced to making stuff up,” Linner said, adding that while he supports access to treatment, supervised sites prevent deaths, making them “the difference between today and tomorrow.”

In a statement, an unnamed spokesperson for Department of Mental Health and Community Wellness reiterated that the province is taking an evidence-based approached and said the Tory government is focused on a “relentless pursuit of recovery for individuals with substance use/addiction.”

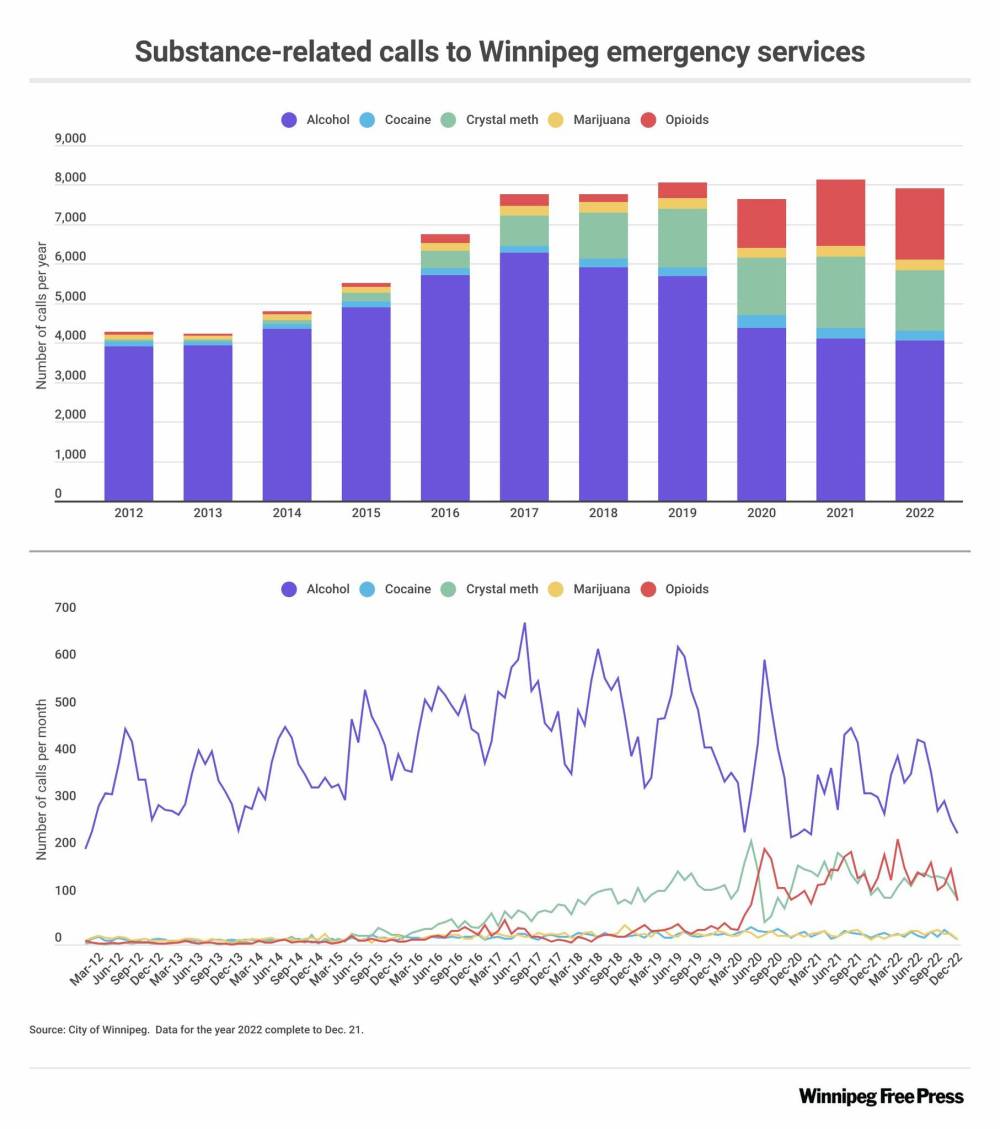

Winnipeg remains the epicentre of Manitoba’s drug crisis.

Last year, more than 400 Manitobans died of overdoses, a number that is expected to climb this year. And looking at Winnipeg specifically, of the 371 overdose deaths in the province in 2020, 271 were in Winnipeg (2020 data is the latest city-specific data made available by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner).

When asked, Winnipeggers say they want supervised consumption sites.

A September Probe Research poll commissioned by the Free Press showed 81 per cent of Winnipeg respondents said they would support safe consumption sites, with 18 per cent opposing the idea.

“In my view, the government needs to catch up to what the public is asking for,” said Sande Harlos, president of the Manitoba Public Health Association, a non-profit advocating for social justice and equity. “People who use drugs and those who love them just deserve our very best. And they are not getting it.”

In an open letter last month, more than 80 organizations called on Manitoba’s provincial government to fund and support supervised consumption sites.

“Our spaces have become injection sites, our doorways, washrooms and alleyways are overdose response sites, and yet this is not enough, we need action now,” they wrote.

“Our spaces have become injection sites, our doorways, washrooms and alleyways are overdose response sites, and yet this is not enough, we need action now.”–Open letter to Manitoba government

While the City of Winnipeg could initiate supervised consumption sites without provincial support, something Saskatoon has done, it seems unlikely new Mayor Scott Gillingham will take this approach.

In a recent interview on the Free Press’s Niigaan and the Lone Ranger podcast, Gillingham said the city doesn’t have the resources to do the work alone.

“The city can’t go it alone. I just don’t think it’s a prudent thing to do,” Gillingham said.

“I’m very open to being a partner in this but the city, while I’m mayor, I can’t see us leading. I just don’t think we have the… resources and the departments to do what needs to be done.”

Stefanson has said she would be “very concerned” if Winnipeg independently put a site in place.

“There are serious risks to individuals, families and communities associated with drug use and consumption sites,” said the Mental Health and Community Wellness department spokesperson when asked what the province’s current position is.

“Appropriate governance and oversight are needed to prevent unintended consequences associated with supervised consumption sites and overdose prevention site.”

Over at Nine Circles on Broadway, a program called The Pit Stop runs Monday to Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

It caters to people who use drugs or are otherwise vulnerable and the focus is on harm reduction — meeting people where they’re at. Clients can pop in to grab clean needles, meth pipes, naloxone, safe sex supplies and everything from socks to food.

Between 75 and 100 people visit daily, said Bailey, the Nine Circles director.

Inside, the space feels warm and welcoming. The walls are newly painted with a mural by local Indigenous artists Jessie Canard and Kianna Fontaine, featuring a bright landscape, a bear, an eagle and a rainbow feather.

This is part of an effort to make the Pit Stop less clinical looking, with Bailey noting clients may have been stigmatized or made to feel uncomfortable in traditional health-care environments.

Bailey is especially proud of the site’s simple, but innovative bathroom initiative.

“I don’t even know what to call them — quasi-supervised sites?” she said.

Years ago, Bailey was working at Nine Circles the day someone died of an overdose inside their bathroom. She’s been fixated on making bathrooms safer ever since.

“I know that it’s not a theoretical possibility that people die behind those doors,” she said. Thankfully, no one has overdosed in recent years with the safer bathroom policy in place, but there have been some near-misses, Bailey said.

At the front desk of the Pit Stop are dozens of informational posters and pamphlets advertising various information and client supports. Two pieces of paper stand out. They sit front and centre, the words DRUG ALERT on each.

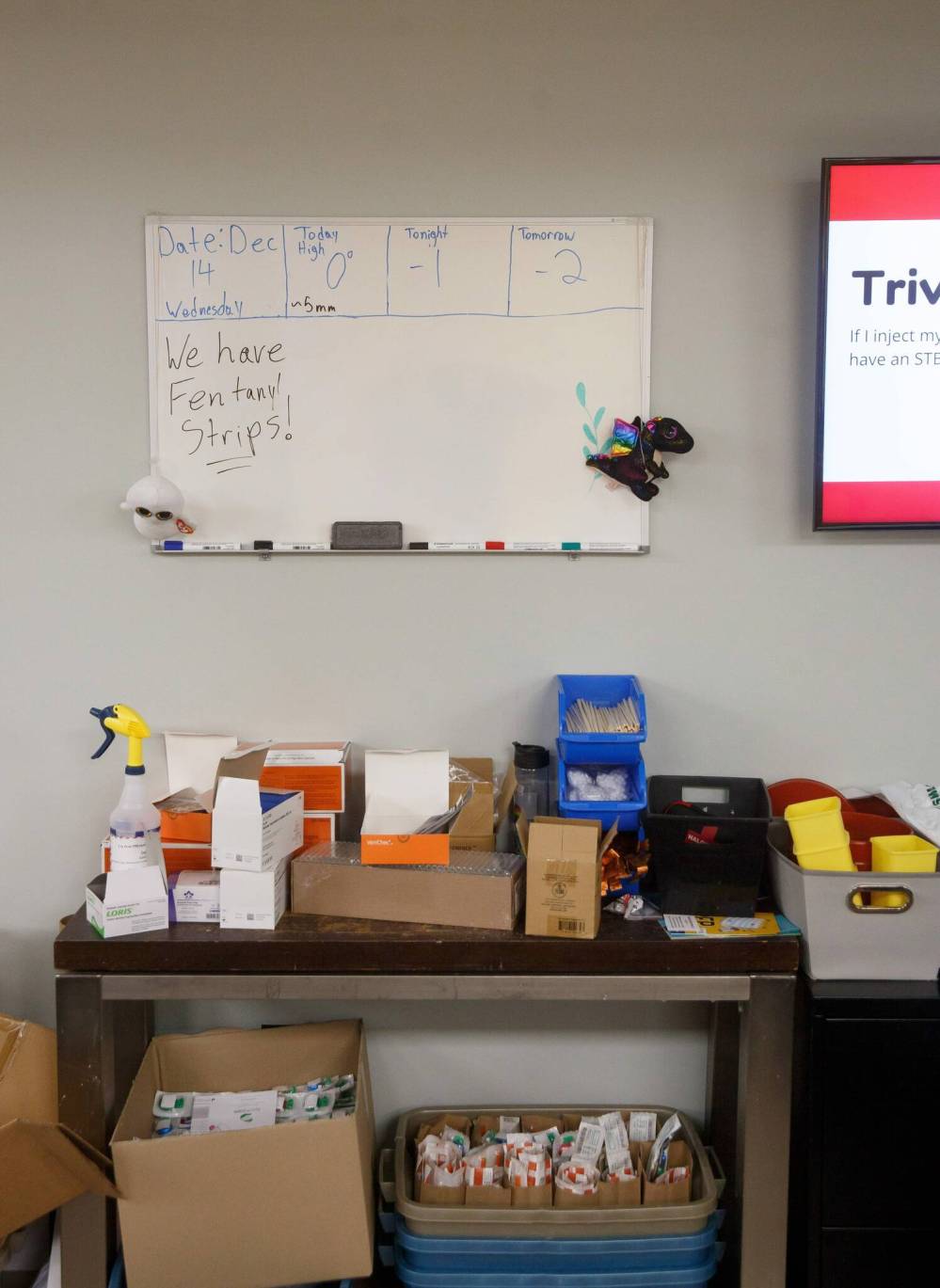

A white board at Nine Circles Community Health Centre is updated daily to provide staff and clients with information such as how cold it will be overnight. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

“Substance sold as DOWN. Really strong batch described as orange and powdery. Folks say it took multiple naloxone kits to revive in two different instances.”

“Substance sold as meth is actually ‘RED DOWN.’ Blood-red in colour. Three overdoses in 24 hours. All survived but weren’t breathing & required CPR and multiple doses of naloxone to survive.”

This is representative of the increasingly toxic and complex drug crisis in Winnipeg, Bailey said. All the more reason why the city needs a supervised site to help people who suffer drug poisoning, not knowing what’s in the drugs, she said.

She would love to see a safe injection site that’s actually set up to do this work.

For now, a travelling RV is the closest thing Manitoba has to such a place.

Winnipeg’s Sunshine House has been running a mobile overdose prevention site (MOPS) since October. The peer-led program involves workers driving a retrofitted “nice, comfy” RV around Winnipeg, stopping where the services are needed by those who use drugs.

People with lived experience are on staff and ready to revive someone if needed, said MOPS co-ordinator Davey Cole.

“We’re there in case things go awry,” Cole said. “We want folks to feel safe when they’re using.”

The estimated yearly budget for the MOPS as a pilot is $285,000 per year, with funding coming from Health Canada’s Substance and Addictions Program.

The federal exemption that allows the site to operate — allowing people to have illicit substances without fear of arrest — is granted by Health Canada, on the basis of urgent public health need. The exemption is valid for one year, until Oct. 31, 2023.

MOPS highlights the need for static sites too, Cole said. In speaking with harm reduction experts from other jurisdictions in advance of launching the mobile program, Cole said people outside the province were routinely surprised Manitoba doesn’t have any supervised consumption sites.

“This province is extremely behind in harm reduction,” Cole said.

Arlene Last-Kolb’s son Jessie died of a fentanyl overdose in 2014. He was 24.

Last-Kolb has since dedicated her life to advocating for people like her son, serving as the Manitoba regional director of Moms Stop the Harm, a group of mothers who call for an end to “the failed war on drugs” through evidence-based prevention, treatment and policy change.

She is an advocate for safe injection sites, but she knows that’s only one step to keeping people who use drugs safe. She also wants to see other harm reduction initiatives, including a safe supply of drugs to those who use them.

“Do I support safe consumption sites? Absolutely. I support them with safe drugs,” Last-Kolb said.

In the same way people use alcohol, Jessie used substances, she said. And he should have had access to a safe supply of opioids the same way other adults have access to a safe supply of alcohol, she said.

Still, if the Tory government can’t get on board with supervised injection sites, she has little faith they will be supportive of a step like supplying safer drugs.

She is critical of the province’s talking points on harm reduction — which include increased distribution of naloxone for reversing opioid overdoses, and more focus on treatment — when asked what they’ll do about the steadily increasing overdose deaths.

“We talk about people dying every single day, they talk treatment… You don’t get treatment if you’re dead.”–Arlene Last-Kolb

“This is insanity that every time we talk about people dying every single day, they talk treatment,” Last-Kolb said. “You don’t get treatment if you’re dead.”

Hundreds of Manitobans have died from overdoses since Jessie died. Last-Kolb has spoken to many of their mothers through her work as an advocate, an infuriating experience for someone who has fought for nearly a decade to make the government act.

“I don’t want other mothers to go through what I’ve gone through,” she said. “There is no more luxury of learning.

“Our government right now is wrong. They are getting it wrong. And it is killing our children.”

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Katrina holds a bachelor’s degree in politics from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from Western University. She has worked at newspapers across Canada, including the National Post and the Toronto Star. She joined the Free Press in 2022. Read more about Katrina.

Every piece of reporting Katrina produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, January 12, 2023 10:24 AM CST: Corrects typos