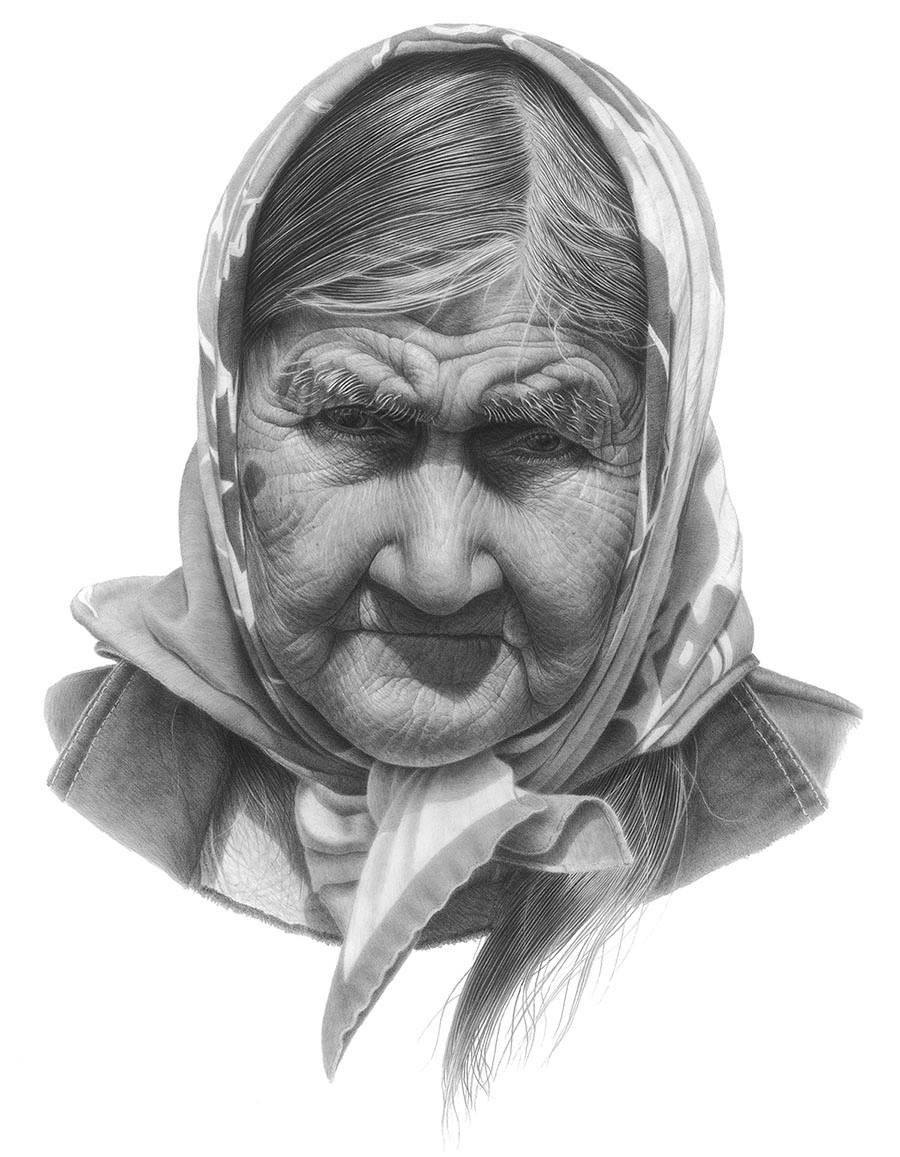

Capturing a moment in Indigenous elders’ lives

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/06/2022 (1371 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Gerald Kuehl has been creating beautiful pencil portraits of Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers from all over Manitoba and the Northwest Territories for 25 years.

The drawings are meticulous and detail every wrinkle, spot and hair, and the exact texture of that person in the exact moment. They are nothing short of mesmerizing.

Kuehl, a self-taught artist and photographer, invited me to his home to see a glimpse of the world of portraits he’s created. We’ve been friends on Facebook for a while. I’m not sure exactly how long, but he shows up on my feed, and I show up on his. When he posts pictures of his work online, I fall over myself to hit the “like” button as fast as I can, because they are stunning.

Kuehl’s portraits, beautifully framed and matted, are hung on walls throughout the home. They are a powerful and exquisite monument to the people he’s met and the stories he’s heard. Most of them hang there only temporarily, until Kuehl can meet with the person he’s drawn to present the gift to them. Each work takes hundreds of hours because of the painstaking attention to detail. In all, he’s drawn about 290 portraits.

The conversation with Kuehl and his wife, Sara, a retired teacher with a warm and inviting smile, flowed effortlessly. We sat in the living room, and Kuehl explained how this 25-year project came to be. Like his wife, he was also a teacher. He worked as one for a handful of years. After one of their sons was born with cerebral palsy, he and Sara decided that she’d go to work and he’d stay home to care for the boys. They called it their five-year plan. When the kids were in school and the chores were done, he’d retreat to the basement to draw, hunched over a table for hours.

“When everything was settled, I would draw,” he said.

Kuehl, who is white, accompanied his friend Reg Simard to Manigotagan — a First Nations community near Lake Winnipeg’s east shore — to meet Reg’s father, Alex Simard, in 1997. The Métis/Ojibwa elder became the subject of Kuehl’s first portrait.

“I have no Indigenous blood. You can’t just walk into an Indigenous community and say, ‘Here I am, can I meet your elders?’ It doesn’t work that way,” Kuehl said.

Alex Simard introduced Kuehl to other members of the community, and those people introduced him to more people.

“This went on and on for about a year. I drew about half a dozen Métis people from Manigotagan,” Kuehl said. “Well, 20 minutes from Manitotagan is Hollow Water, so he (Simard) takes me there. Because of all of the intermarrying going on, he knew everybody in Hollow Water, so then I met Roddy Raven, Dora Monias, Frank Monias, a whole bunch of people. I just loved it.”

The more people Kuehl met, the more he learned. He developed relationships and built a portfolio that helped him meet new people in other communities. He has spent a quarter of a century of his life travelling to communities throughout northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories, learning from the traditional peoples of this land. He is humble but speaks excitedly and enthusiastically about the people he has met and had the honour to draw. It’s almost as though he can’t speak fast enough when he explains about the teachings and stories that have been shared with him and the encounters he’s had.

Kuehl has published Portraits of the North, Portraits of the Far North and Portraits of the Plains. The latter is a collection of drawings and profiles of the Dakota/Sioux and Saulteaux/Ojibwa of the Canadian plains.

He said that for every $1 he spends, he probably invests $1.50 back into his work.

In the basement is a studio where Kuehl has set up a framing station, where he mats and frames a large print of each portrait before presenting it to the subject.

He draws in another section of the basement, tucked away beside the stairs. It’s a tiny area, though he makes use of every piece of space. His custom-made easel was built by a friend. Before acquiring it, he would spend hours crouching over a table to draw. Beside the easel is a collage of old photographs, a patchwork of old pictures of elders — many who have long made their journey to the spirit world. Each capture is filled with expression, though none the same as the next, which he translates so beautifully into his portraits. It’s uncanny.

He remembers each person’s name and the details of their visit. Each connection is meaningful to him. It’s all tucked away in the Rolodex in his mind.

Kuehl has met all of his portrait subjects, except for Sgt. Tommy Prince. He took the initial photos of the subjects and listened to them share their stories, often through a translator.

Early on, one experience in particular left a profound impact on Kuehl. He was meeting with Dora Moneyas, an Ojibwa elder from Hollow Water First Nation. (Her portrait is a permanent fixture in his home.)

“I was photographing Dora behind her home, and I’ll never forget it. She had just finished what you call brushing — she was always working… and I got her over for some photographs. As I was photographing her, I am looking through the viewfinder, and I got hit by this warm light — literally a cascade of heat that just poured over me,” he said, staring at the image of the elderly matriarch in a headscarf with deep wrinkles and a discerning look on her face. “And I went, ‘This is what I’m meant to do.’”

Kuehl’s portraits have been showcased in many museums, art galleries and cultural centres, and in First Nations and Inuit communities. You can see his work at geraldkuehl.com.

shelley.cook@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @ShelleyACook

History

Updated on Monday, June 13, 2022 11:51 AM CDT: Photo added.