Festival riffs off Main Street’s storied past

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/06/2022 (1373 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Fifty years later, Billy Joe Green can still remember one of the biggest breaks of his career. It was 1971, and his band was asked to become the house band at the Brunswick, an old Main Street hotel and bar.

People would line up around the block to see them, and for a while Green, who was barely out of his teens, could really feel as if he’d made it.

“That was like the high-end place to play for our people,” he says, with a nostalgic smile.

Oh, if the walls of the Main Street strip could talk, they would tell a million stories, and Green would be in a bunch of them. An Ojibwa man and member of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, Green is one of Winnipeg’s most iconic blues guitarists; back then, he was jamming on the Main Street circuit, slinging out country and rock hits.

For decades that strip, stretching from Rupert to Higgins, was a bustling place, dotted by bars in well-worn hotels. They weren’t always pretty and the scene wasn’t too gentle, but it was a popular social hub for Indigenous people; for musicians such as Green, who became the name-brand stars of the strip’s stages, it was home.

“When we played, there’d be a chair flying by, but we didn’t think nothing of it,” he says, with a chuckle. “We’d keep playing, and of course we felt safe in that environment despite all the rambunctiousness that went on… We attracted our own people to the clubs, and all the pretty girls used to come.”

”When we played, there’d be a chair flying by, but we didn’t think nothing of it.”–Billy Joe Green

Partly, there weren’t many other places for them to go. The big downtown clubs wouldn’t book musicians such as Green and his friends: “It was kind of an apartheid thing,” he says. “(They) didn’t want to attract the people that followed us around.”

In other words, they didn’t want their clubs filling up with Indigenous fans. So those musicians, and their audiences, created their own culture in the old bars, by the shadow of the railway tracks.

“It was pretty rough, but we had lots and lots of fun as well, and our people love to have fun, and they love live music,” Green says, chatting in the gallery at the Edge Urban Art Centre, one door down from where he used to play. “Many of us stuck it out here because we couldn’t play the main clubs downtown, but we were very welcome in here.”

There was the old Occidental Hotel, at the corner of Main and Logan: “that was a rowdy place, oh my God,” Green says. Not far from that was the Savoy, which was beside another hotel bar called the Manor, which had been fixed up into what Green recalls as a “really nice place.” Across Main from there was another hotel, rougher, that Green played a few times.

As the years turned, some of the musicians who cut their teeth in those clubs became famous, people such as Shingoose and Tom Jackson. Most just kept slugging it out on the circuit. Over time, some of the life of the place began to ebb away as venues closed, streets lost buildings to decay, and the rest of the city treated the strip as a problem to be solved.

”It truly is a community… A lot of people in the suburbs, they don’t see that.–Richard Walls”

Today, there’s a parking lot where the Brunswick used to be. Where Green once jammed at the Savoy and the Manor now sits the Youth for Christ centre. And the Occidental, well, that is a much longer story: it was transformed into the Red Road Lodge, a 47-room sober transitional housing facility with support services and an art-focused approach to healing.

But the people who played their hearts on the strip every night never forgot it. On Saturday, that creative spirit will be celebrated on the strip once again, as a coalition of community members comes together to host a new day-long festival of the area’s cultural identity, both present and past.

It even has the perfect name: Main Street’s Got Talent.

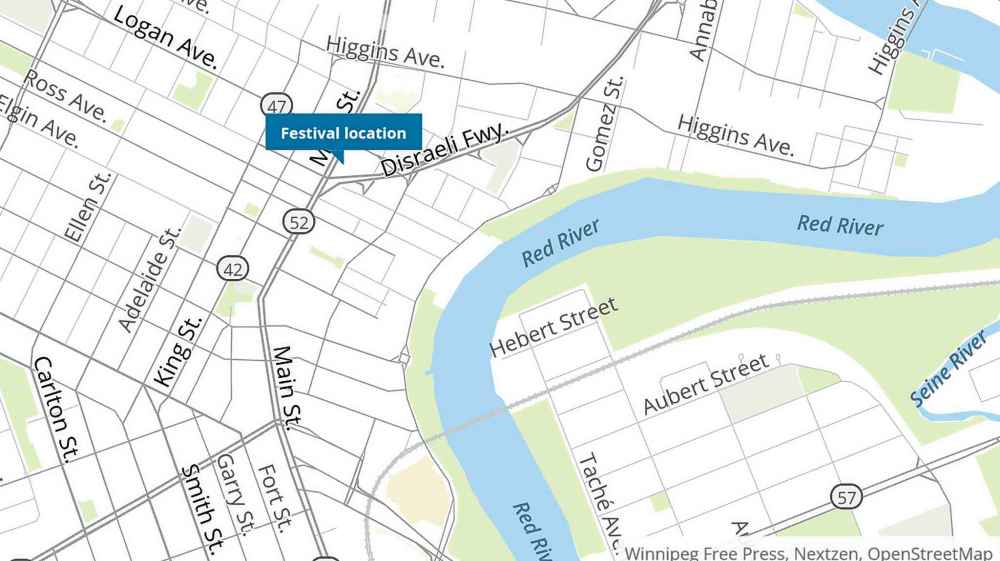

The event, which will take place in and around a parking lot between Red Road Lodge and the Edge Gallery at 611 Main St., will unite many forms of expression. Green will perform, along with a host of other top-notch Indigenous musicians. A teepee will be raised just after dawn, and the day will feature art displays, art-making and other activities.

The idea was spearheaded by Richard Walls, the founder of Red Road Lodge. From the time he’d first bought the Occidental over 15 years ago, he’d been intrigued by the history of the area, and the way it had long been a hub for Indigenous culture; he remembers seeing artists working at the old bar tables, before taking their work to sell on the street.

So when he transitioned the bar to become Red Road Lodge, he made art a big part of its mission. In recent months, as the community of businesses and non-profits around the strip has begun to work more closely together, he started thinking about how to take the talent he saw inside the Lodge, and the Edge he’d founded next door, and take it outside.

This is a key part of changing misconceptions. Many of the folks who live in the community are unhoused; many live with addiction. Misconceptions of who they are, and what the strip must be like, keeps many Winnipeggers away; but if people never see the fullness of their lives, then they will never know the whole truth of the city.

“You gotta look at the human being, and start recognizing that so many of them have talent,” Walls says. “They could be a guitarist or a fiddler. They could be a writer. Talent has to be recognized in all its forms, and we have to get to the public to recognize Main Street for the positive things that are here.”

So a party it is, then, to celebrate the artistic brilliance that has never once left the strip. All day at Main Street’s Got Talent artists will work on and sell their pieces. There will be community art projects, such as an invitation to make handprints in clay. They will paint a canoe, which will be hung from a nearby arch on display.

“It’s all coming together to be a first-class event,” Walls says.

It is, above all, a team effort. Some of Red Road Lodge’s 47 residents will contribute, either with their art or their time. There will be a morning prayer by elder Delores Kelly, a drum ceremony, fiddling and a dance performance by the Ivan Flett Memorial Dancers, a trio of Métis siblings who recently starred on Canada’s Got Talent.

“It truly is a community,” Walls says. “A lot of people in the suburbs, they don’t see that.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.