Worrisome levels of lead found in school drinking water

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/05/2022 (1307 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

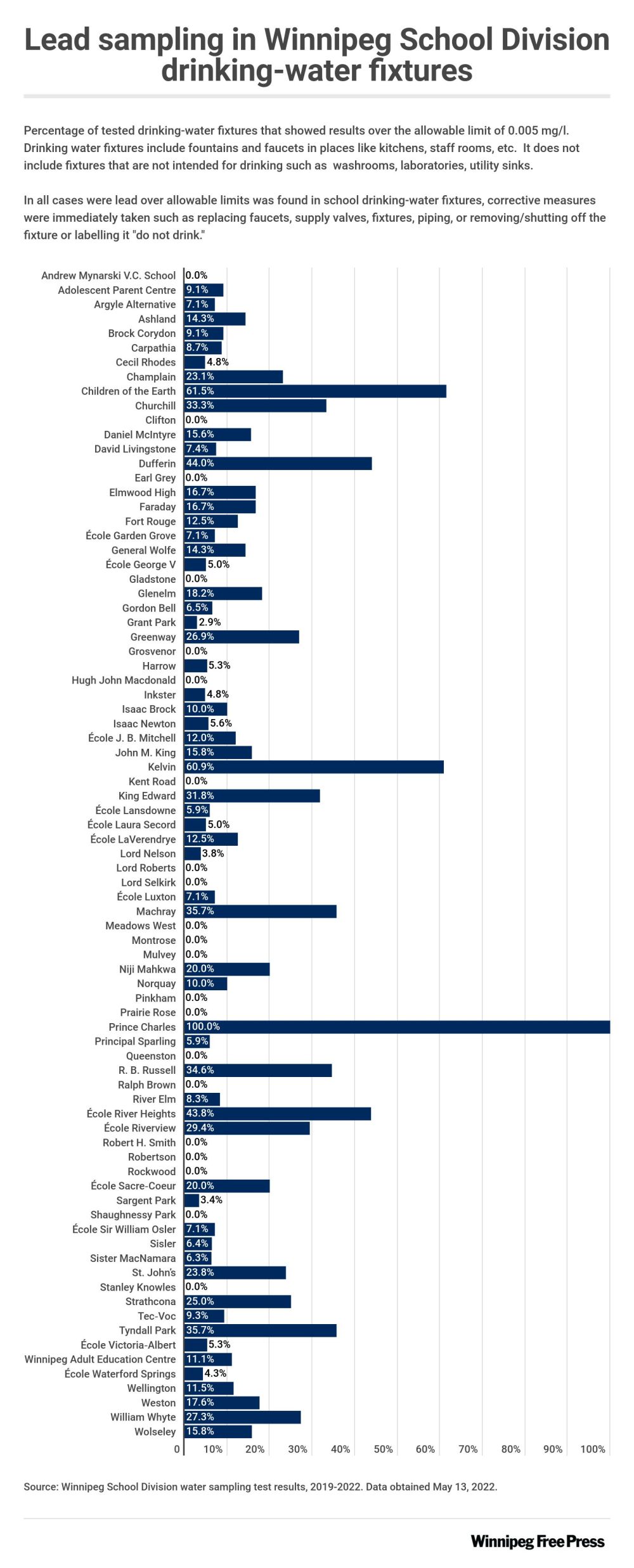

The majority of drinking water samples taken from Children of the Earth and Kelvin high schools contained concerning levels of lead in a recent review of fountains, kitchen taps and other fixtures in K-12 buildings in central Winnipeg.

Manitoba’s largest school division released the results of a provincially mandated lead-testing program in its administrative buildings and learning facilities.

Between 2019 and 2022, water from at least one drinking or non-drinking fixture in 76 of 82 buildings subject to testing in the Winnipeg School Division was found to contain lead that exceeded federal guidelines of 0.005 mg/L.

In 10 facilities, all but one of which are schools, samples from more than 30 per cent of potable fixtures had high lead levels.

Children of the Earth and Kelvin topped the list of schools with worrisome metal concentrations, with 62 and 61 per cent of respective drinking water tests coming back with higher-than-allowable lead levels.

Dufferin, River Heights, Machray, Tyndall Park, R.B. Russell, Churchill and King Edward were next, in that order.

All of the samples from an education resource centre at 1073 Wellington Ave. surpassed safety guidelines.

A lengthy list of corrective actions taken to fix troublesome taps — including posting “do not drink” signage, replacing equipment, and turning off fixtures — has been published on the division website.

“This was a huge undertaking,” said Mile Rendulic, director of buildings for the division. “We were trying to eliminate any sources of lead that we could find in the division. In a lot of schools, we were able to do that. In others, not so much.”

Over the last three years, maintenance staff have surveyed upwards of 5,000 fixtures, a process that Rendulic said has cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in testing and mitigation measures.

The division prioritized elementary schools during the process because young children are at a greater risk of experiencing health issues if they consume excessive amounts of lead, he said, noting that none of WSD’s incoming water services has lead pipes.

The toxicity of lead — which typically leaches into water from distribution and pipes because it was historically used in service lines, plumbing fittings and solders — negatively affects cognitive and behavioural development in children. High blood-lead levels are believed to reduce IQ scores.

While Health Canada encourages “every effort” to maintain lead levels in drinking water as low as reasonably achievable, the federal agency lowered the maximum acceptable concentration from 0.01 mg/L, set in 1992, to 0.005 mg/L in 2019, citing the latest science.

Leakage issues in schools usually arise because they have solder and brass in their plumbing systems and the maximum metal limit in products has changed over the years, said Evelyne Doré, a Montreal researcher who completed her PhD in lead and copper in large buildings.

The research fellow at Polytechnique Montréal said there is a higher prevalence of lead in older schools due to old infrastructure, but modern buildings are not exempt from seepage because new fixtures release excess metal as they get acclimated to water.

That could explain why several taps in WSD’s newest elementary building: École Waterford Springs School, completed in 2021, yielded concerning lead levels, Doré said.

To mitigate risk, she suggests schools downsize their tally of drinking sources to ensure water is being flushed consistently through working fixtures, and visitors fill water bottles at fountains instead of washroom sinks because the latter are not necessarily designed to release potable water.

“If your fixture is old and there is lead in it, let the water run… Kids should be educated and be told that they should let the water run before they drink it, at least if they’re the first one in line. If you’re the 10th one in line for the water fountain, you’re fine,” said Doré.

University of Manitoba scientist Francis Zvomuya said if he had children enrolled in one of the K-12 buildings that was found to have high levels of lead in tap water, he would send them to school with safe drinking water.

Ottawa’s decision to lower the allowable lead limit several years ago is a reflection of significant progress made on the filtration front and it would not be surprising if the cap is dropped again in the future, said Zvomuya, a professor who oversees soil science at the U of M.

“Any measurable lead that we have in drinking water is potentially risky to human health,” he said.

For that reason, Zvomuya said transparency around lead exposure is critical, so he is pleased more institutions are making reports available to the public.

WSD shared the results of its testing program with families this week.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.