Money for nothing? Manitoba has invested $58 million into mental-health and addiction services since 2019 but the number of opioid-related deaths is growing, devastating families and frustrating health-care workers and activists with solutions who are being ignored

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/04/2022 (1339 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Tracy Sanderson’s world has been torn apart by opioid addiction, even though she’s never touched the deadly drugs.

The Winnipeg grandmother lost her 27-year-old stepdaughter Melissa to suicide in 2008, a tragic end to a life destroyed by opioid addiction.

Five years later, she found her youngest daughter Alexandria — an 18-year-old first-year University of Manitoba student — dead from a fentanyl overdose. When a small piece of foil fell from Alexandria’s face, Sanderson knew it meant she’d been smoking the drug.

She knew that because her older child, Kelsie, now 31, began using fentanyl in 2007 at the age 16.

“(Alexandria) hid it from us very well, but I wasn’t looking,” says Sanderson, 58. “I’m sure if I was looking, I would have seen the signs.

“I wasn’t looking at her. I was busy trying to keep my other daughter alive.”

It took years for Sanderson, a retired social worker, to acknowledge how Alexandria died. She then became an advocate with Overdose Awareness Manitoba in 2016.

As she watches the number of opioid-related deaths rise in Manitoba each year, she feels sadness, but not surprise.

“Because of the lack of resources, because of a lack of government stepping in and doing anything to try and stop this epidemic,” she says. “They throw a few bucks here and there… there’s not enough harm reduction.”

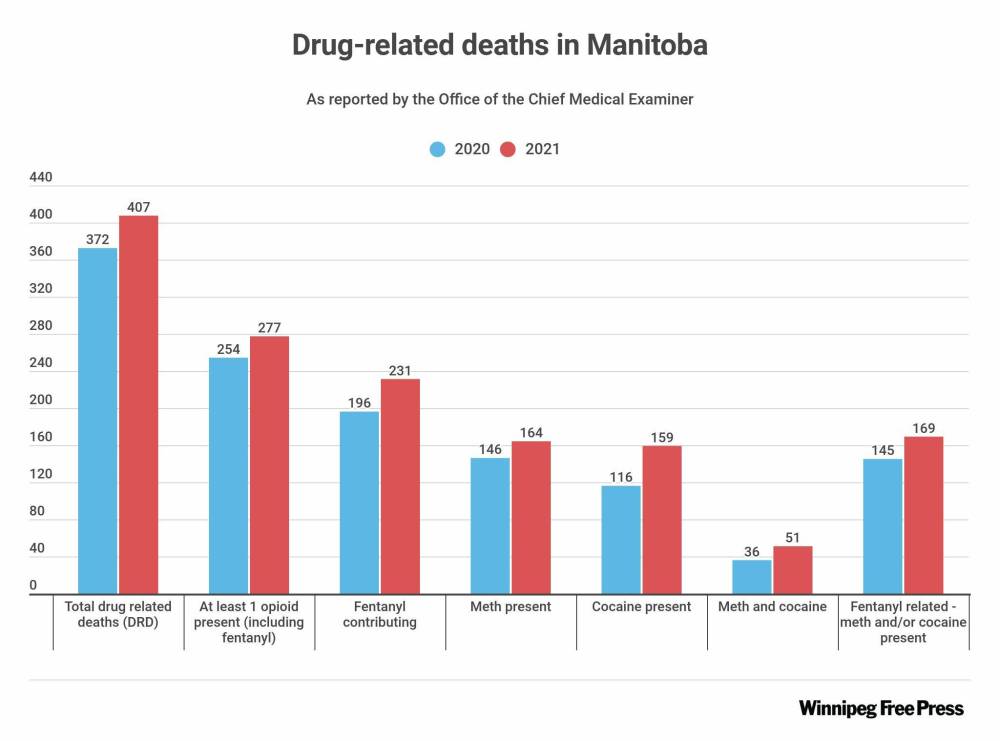

Overdose deaths have risen steadily in Manitoba since 2019, when there were 200; the number increased to 372 in 2020 and 407 in 2021.

The statistics don’t come as a surprise to those who work with people battling addictions.

A health-care worker at a Winnipeg Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine clinic, who asked to not be named, says the facility is run by devoted staff but doesn’t have the resources to meet the growing need.

RAAM clinics are drop-in centres for people who want help with substance abuse. They’re a low-barrier option for people who’ve decided they’re ready to get help. They can get counselling and other support, including prescriptions for medication to dull their cravings. There are two in Winnipeg — 817 Bannatyne Ave. and 146 Magnus Ave. — and one each in Brandon, Portage la Prairie, Selkirk and Thompson.

The health worker’s clinic sees from 16 to 22 people daily, including patients they’re following up on and new walk-ins. People are turned away when the clinic has hit capacity. Clients don’t have to be sober, but can’t enter if they’re “too” intoxicated. Anyone behaving violently or aggressively won’t be admitted.

A client is assessed by a nurse to determine which drugs they use, how they are affected by withdrawal and what the client wants to happen.

“Sometimes either their needs, wants or requests are just beyond what we can give,” he explains. “I can’t get someone into, say, a treatment program tomorrow.”

If someone has been turned away, he says they will “move heaven and earth” to get them in.

“Personally, every person that we don’t see, or we have to turn away, there’s a little voice in the back of my head saying, ‘Is that the one you’re gonna read about (in the obituaries) on Saturday?’” he says. “And that’s hard. That breaks my heart.”

”Every person that we don’t see, or we have to turn away, there’s a little voice in the back of my head saying, ‘Is that the one you’re gonna read about (in the obituaries) on Saturday?’”–RAAM clinic worker

He’s been in health care for decades and has worked with RAAM clinics since they were introduced in Manitoba in 2018.

He says the provincial government has little interest in improving supports for people with addictions, and he calls that “disgusting.”

“The government doesn’t see us with the same needs, in my personal opinion, as they do others,” he says.

In its 2022 budget unveiled Tuesday, the province set aside $1 million to expand capacity and hours at RAAM clinics.

After the Free Press requested a comment from Mental Health and Community Wellness Minister Sarah Guillemard, a spokesperson emphasized the province has invested $58 million in 40 projects since 2019 “to improve mental health and addiction services throughout the province.”

The health-care worker argues that small amounts of money earmarked for different projects makes it difficult for treatment providers to offer streamlined services.

“I get very frustrated, because if you look at the (Addictions Foundation of Manitoba) building on Portage Avenue… If you really want to make addictions treatment what it needs to be, knock that place down, and put a 10-storey building with every resource: us, treatment, detox, counselling, followup, addictions physicians,” he says.

“Put all that under one roof and stop piecemealing it where people are going from here to there, to here to there.”

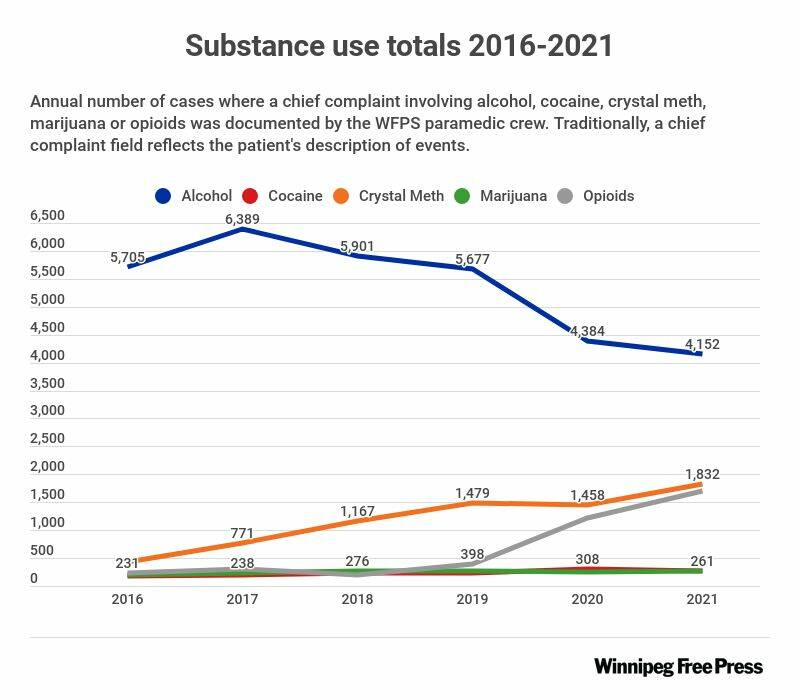

He says drug-related deaths have spiked during the pandemic because the available supply of illegal substances became tainted when the Canada-U.S. border closed. People began making some of it themselves, using unsafe ingredients.

“We have a lot of fake drugs in Winnipeg,” he says.

In 2021, 38 people died after overdosing on a mix of fentanyl and etizolam. It marked the first year etizolam (a sedative prescribed for anxiety and insomnia that, when combined with fentanyl, can be fatal) was listed as the cause of a drug-related death in Manitoba.

“I really wish (Health Minister) Audrey Gordon would come down and spend the day with us, or spend half a day with me. Come spend half a day and see the people, come see the families, come see the children who come with the parents that are addicted and stop throwing dribs and drabs of money,” he says.

“Just because addicts aren’t pretty, and that’s why they’re not given the money or the resources that’s necessary.”

”I really wish (Health Minister) Audrey Gordon would… come spend half a day and see the people, come see the families, come see the children who come with the parents that are addicted and stop throwing dribs and drabs of money.”–RAAM clinic worker

People seeking help at the clinic have ranged from the well off to those who have lived on the streets for decades. He’s seen police officers, doctors, engineers.

“I’ve seen friends die. I’ve opened the paper and they’re dead, they’ve killed themselves, overdosed,” he says. “It brought me into this, because it makes me angry, because no one has to die from addiction. No one.”

In 2020, the provincial government promised $890,000 over three years to set up eight more beds to help get patients quickly transferred from RAAM clinics into detox. There are currently 82 detox beds in the province, five of which are closed in Thompson and eight at Main Street Project owing to staffing and pandemic issues.

Six beds have been added since the pandemic started, all mobile beds at Klinic in Winnipeg.

Arlene Last-Kolb, co-founder of Overdose Awareness Manitoba, says there’s no point in funding more beds if users have no way to ensure the drug they use won’t kill them.

“If we don’t start talking about the supply, people will continue to die. We couldn’t provide enough treatment and health for all of these people,” she says.

“Not everybody who uses substances wants treatment, but they want to know that they’re safe. And what is happening here is we have a supply out there that is unsafe, and people are not consenting to this. If we had wine that was poisoning people, it would not be happening, because people did not consent to take that poison in their wine.”

”If we had wine that was poisoning people, it would not be happening, because people did not consent to take that poison in their wine.”–Arlene Last-Kolb

The provincial government won’t consider the proposition that people in Manitoba who use drugs deserve to use them safely, be it through drug-checking services or safe-injection sites, says Last-Kolb, who lost her 24-year-old son to a fentanyl overdose in 2014.

“My frustration comes from when I do these monthly meetings with our harm-reduction community, and all the different people that work with people that use substances,” she says.

“And when I meet with my families, it’s a completely different conversation than when I have a conversation with government. I don’t know how else to say — they’re not listening, they’re not paying attention.”

● ● ●

At the municipal level, conversations focusing on safe use and decriminalization are ramping up, but not getting to the finish line.

A recent motion tabled by councilors Sherri Rollins (Fort Rouge-East Fort Garry) and Markus Chambers (St. Norbert–Seine River) for the city to ask Ottawa to create an exemption allowing Winnipeg to decriminalize possession of small amounts of illegal substances was shot down in an eight-eight tie.

Rollins has been calling for a harm reduction-based approach to Winnipeg’s drug problem for years, asking for supports including supervised consumption sites for people to test their drugs without fear of arrest.

She says the motion was shot down, in part, because many councillors don’t believe addressing the city’s drug-addiction problem is among their responsibilities.

For years, she has requested meetings at the provincial level to discuss the problem but has never received a response.

“The stark failure of government, and the stark differences between this province and this city, and any other capital city in Canada is astonishing,” she says.

”The stark failure of government, and the stark differences between this province and this city, and any other capital city in Canada is astonishing.”–Coun. Sheri Rollins

Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec all have open supervised-consumption sites. The City of Edmonton is currently moving forward in the process to decriminalize personal possession of drugs. Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto have asked the federal government do the same.

“The pressure that I see groups and community-based organizations under is unreal, but the sheer amount of mourning that families are going through, the trauma and the silencing, because we don’t even have the narrative in this province that many other provinces have in terms of harm-reduction services,” she says.

● ● ●

Away from the health workers’ frustrations and political debate about what should and shouldn’t be done, the people with addictions struggle to live another day.

Kelsie Sanderson, Tracy’s 31-year-old daughter, is in a sober-living home. She’s been in public and private treatment centres multiple times since she first tried fentanyl at 16.

“(Alexandria) was my best friend. That was really hard on me, I carry a lot of guilt surrounding her death,” she says.

“I had a really hard time trying to get myself to heal from that, because I honestly didn’t think that I deserved it, until I started going to meetings and connecting with people with similar stories and learned that it wasn’t anybody’s fault.”

Kelsie has been sober for stretches since; her sons, now 11 and four, were born while she was clean. When COVID-19 hit, she relapsed again after finding it difficult to access the resources that were helping her get by.

“(During) the COVID pandemic, my depression had skyrocketed, my anxiety had gotten really bad and I didn’t know how to get help, because I wasn’t sure what was open and what wasn’t, because everything was shut down,” she says. “And then things would open up again, when they thought numbers are going down, and then it would close again.”

A year ago, feeling hopeless about the future because of the pandemic, she transitioned from using fentanyl to “down” — a combination of fentanyl and heroin.

“My life had gotten so bad, it had gotten so unmanageable, that I didn’t think that I was going to make it out alive, which scared me,” she says.

But she checked herself into the sober-living home after five previous attempts. She’s hopeful.

”You can’t understand unless you’ve been through it, or have seen it first-hand, or have had your family be torn apart from it.”–Kelsie Sanderson

She wants to eventually get her high school equivalency General Education Development certificate and reunite with her two boys now under Tracy’s care.

She dreams of going into social work like her mother. And Alexandria, who planned to follow her mom into the field and worked part time at a women’s shelter when she was 18.

In the meantime, she hopes people will be empathetic when reading her story.

“You get a lot of negative opinions from the outside people who have never seen it or have really had someone they know (go) through it, so it’s really easy to say bad things about people who have struggled in addiction or alcoholism,” she says.

“But you can’t understand unless you’ve been through it, or have seen it first-hand, or have had your family be torn apart from it.”

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

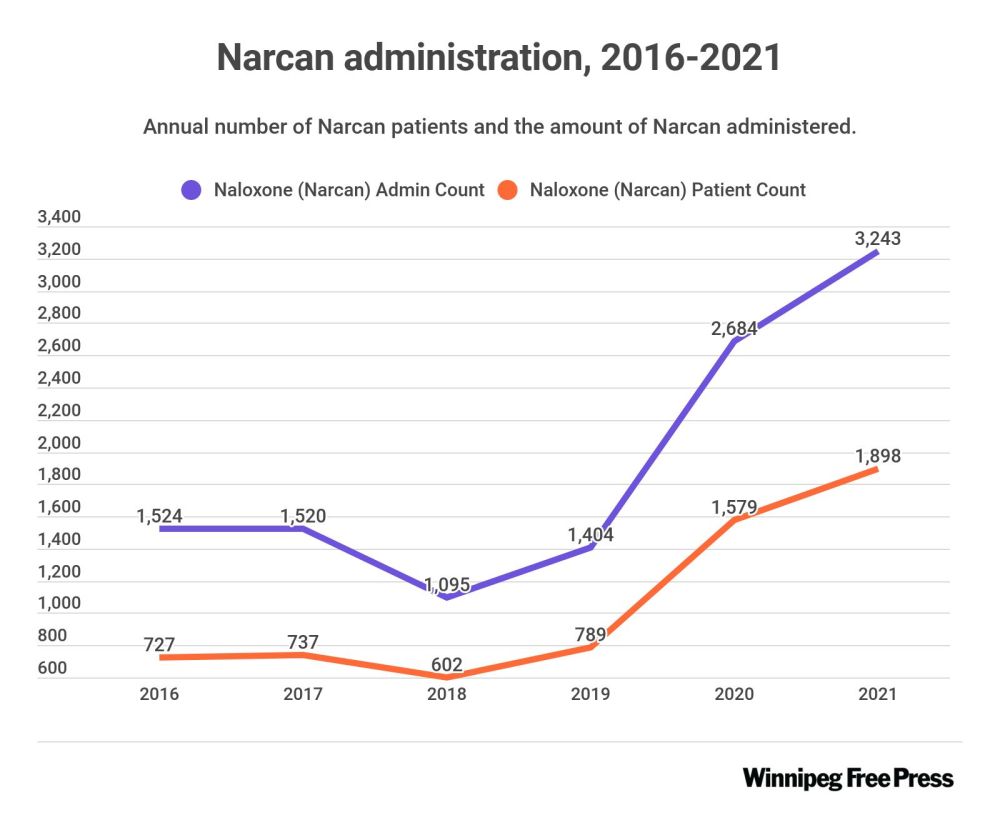

Updated on Monday, April 18, 2022 11:05 AM CDT: Updates Narcan graphic to remove reference to olazipine.