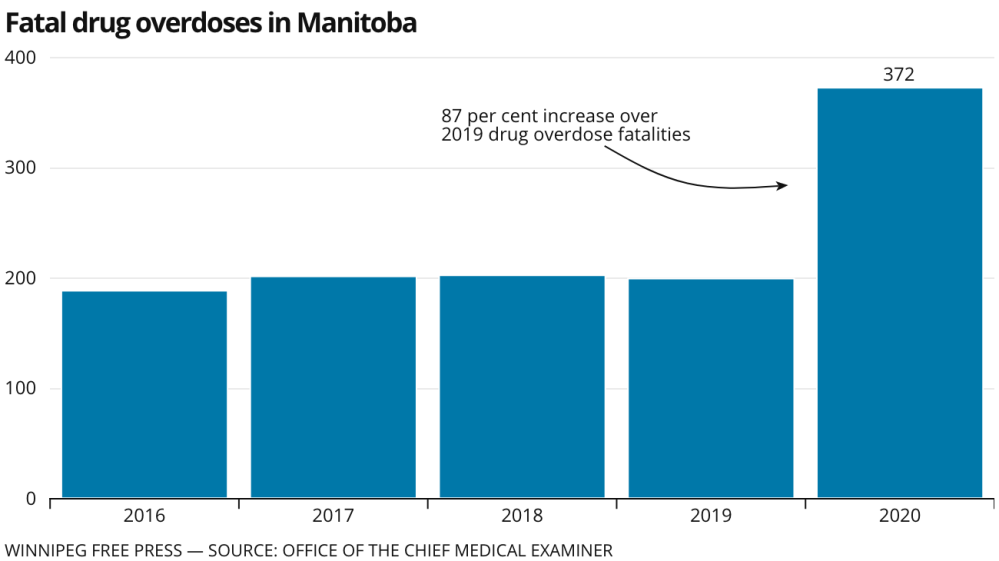

Drug overdose deaths spike by 87 per cent in 2020

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/04/2021 (1699 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Annual drug overdose deaths reached an all-time high in Manitoba, after 372 people died in 2020, marking an 87 per cent increase in reported deaths over 2019.

“We knew it was going to be high, but it doesn’t make it easier when you see these numbers,” said Rebecca Rummery, co-founder of Overdose Awareness Manitoba. “It’s people we’re talking about, and they all have families and loved ones.”

Rummery added that she receives messages daily from people affected by drug overdoses and those unable to find treatment programs for their loved ones.

“There is still no immediate access to government-funded treatment. We are still the only province west of Quebec that doesn’t have a safe consumption site, and we petitioned the government for a medically assisted detox in 2019 and still haven’t seen action with that,” she said in a statement Tuesday.

Rummery lost her partner Rob to an accidental drug overdose in 2018. Later that year, she co-founded Overdose Awareness Manitoba with Arlene Last-Kolb, whose son Jessie had died from an overdose.

“The overdose crisis is a Manitoba public health emergency that is being forgotten about,” Rummery said.

Shohan Illsley, the executive director of the Manitoba Harm Reduction Network said she’s “saddened” but “not shocked” by the data.

The network sent an open letter to the province last spring in which it asked to meet with officials to discuss ways to mitigate overdoses. It predicted fatalities would climb under pandemic restrictions.

The lion’s share of overdose deaths happened during the last part of 2020, coinciding with pandemic restrictions and lockdowns between provincial and international borders, Illsley said.

The network received data from the province’s chief medical examiner that showed 138 people had died from an overdose during the first half of last year, and 234 people died the same way from July to the end of December.

“What we know is that people were going to have to use alone. It was going to increase the risk for an overdose,” Illsley said. “We also knew that once borders closed and things like that started to take place that it would increase the risk for drug poisoning.”

Timely data could help prevent overdose deaths, Illsley said.

“If we knew that, for example, a supply in Winnipeg is adultered and someone died of a drug overdose, we would be able to release that information out to the community,” she said.

Rummery wants to see affordable, streamlined and extended care for Manitobans seeking help for drug use. Right now, some individuals travel to other provinces to access less expensive private treatment options, she said.

“We have a lot of families taking mortgages out on their houses just to be able to afford (treatment) for their loved ones,” she said.

Rummery added that 28-day government-funded treatment doesn’t provide many people with the time needed to address the trauma that fuels their drug use.

At a news conference Tuesday, NDP Leader Wab Kinew voiced the need for a more progressive approach to drug treatment.

“It’s long been clear that there’s a need for a safe consumption site in Winnipeg as part of an overall approach to combatting addictions that’s grounded in harm reduction,” he said.

While there are no safe consumption sites in Manitoba, last year, the province made naloxone — a medication that temporarily reverses opioid overdoses — more accessible.

Before last year, only health care providers could administer the medication.

“Cleary that was not enough. We still have an increase in overdose deaths happening,” Illsley said.

Anyone who is at risk of overdosing on opioids, or has a family member or friend who could be, can get up to two free naloxone kits from the province.

Some pharmacies carry a nasal spray version of naloxone. The sprays cost, on average, $60 to $250, Illsley said.

fpcity@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, April 20, 2021 6:42 PM CDT: Adds graphic