Left for dead

It took a crisis weekend for authorities to finally respond to stricken care home

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/02/2021 (1858 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

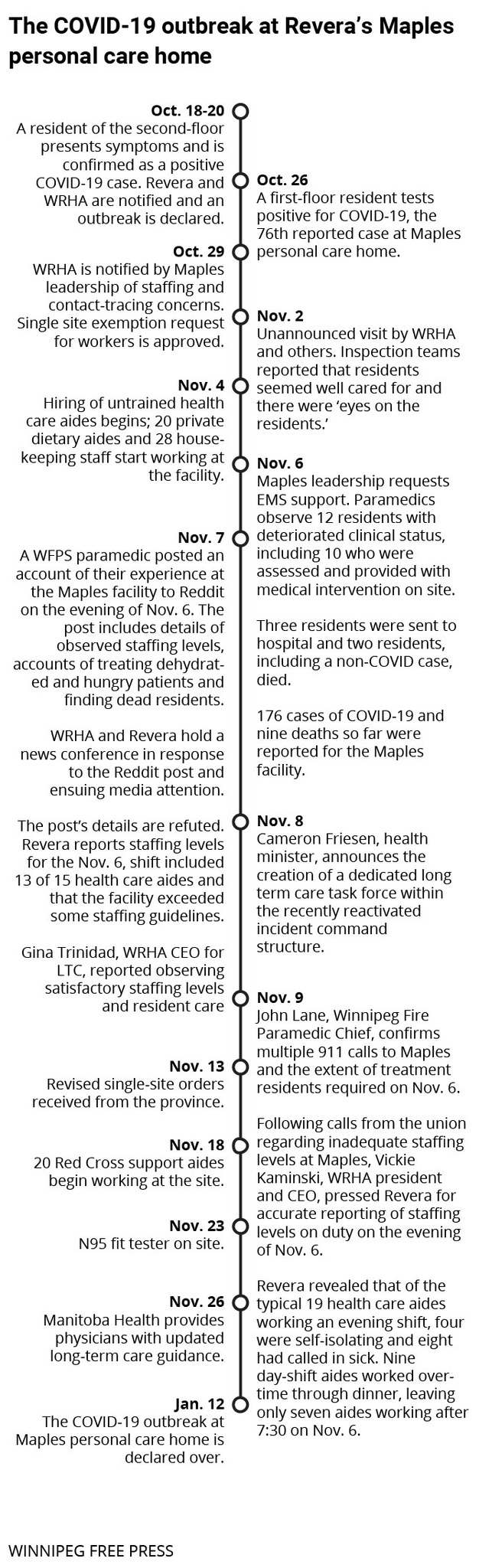

Despite the desperate pleas of family members to the Manitoba government to send help to their loved ones at Maples Personal Care Home, which was stricken with a COVID-19 outbreak last fall, health officials failed to notice the emerging crisis.

In late October, families with loved ones in Maples told the media they were seriously concerned about staffing levels and infections. That was a week into what became the province’s largest and deadliest personal care home outbreak.

Their pleas for help were amplified by politicians and unions who wanted the Canadian Red Cross, military and Winnipeg Regional Health Association leadership deployed to the home.

Yet, WRHA executives told external reviewer Lynn Stevenson — who was commissioned by the provincial government to investigate the outbreak response — that they “were not aware of the magnitude of the situation” until Friday, Nov. 6, when the crisis came to a head, according to Stevenson’s report, which was released Thursday.

On that Friday in November, health-care workers on the evening shift were desperately short-handed and could not keep up as the condition of a dozen residents deteriorated quickly. Eighteen calls were made to 911 and over a 48-hour period, eight residents died.

Eddie Calisto-Tavares was part of the chorus calling for the province and the regional health authority to intervene earlier. Calisto-Tavares was volunteering to care for her elderly father, who was sick with COVID-19 in the home.

“I know it’s a disaster,” Calisto-Tavares told the Free Press on Nov. 2, the same day she wrote to the health minister, Cameron Friesen, to appeal for help. “They don’t have staff (at Maples). They have 20-plus staff in isolation because they all tested positive for COVID.”

Public health declared an outbreak at the seniors home in northwest Winnipeg on Oct. 20. Ten days later, 92 residents had tested positive, as had 15 staff members.

Dr. Samir Sinha, director of geriatrics at Sinai Health in Toronto, said in other provinces an outbreak of that size would trigger an immediate visit to the home by the relevant health authorities and an offer to provide staffing and personal protective equipment to the operator.

“Too many of these homes initially were left for dead because you had a (health) minister at the time who was famously quoted as saying, well these deaths are sadly tragic, but they’re ‘unavoidable,’” Sinha said, referring to comments made by Friesen to CBC Manitoba in mid-October.

“Maybe that tone and that understanding was really reflective of the initial response and how seriously or not seriously these things were being taken.”

Stevenson’s review pointed out faults in pandemic planning, preparation and communication across all levels, including Revera, the operator of Maples care home; the WRHA and the provincial government. She also noted Revera made “significant efforts” to find staff to support the home and made multiple requests to the WRHA and the province.

The report says health officials first visited Maples on Nov. 2. Significant concerns, including staffing, were noted and Revera was required to report back, Stevenson wrote, but no additional resources were offered to support the operator.

However, at a news conference on Nov. 9, WRHA chief executive officer Vickie Kaminski said the Nov. 2 visit raised no “obvious concerns” and residents seemed well cared for, but acknowledged that the condition of people with COVID-19 can rapidly decline.

As the outbreak ballooned throughout October, the province was scrambling to bolster its provincial recruitment and redeployment team and COVID-19 casual worker pool, both of which were unable to meet the demands of care home operators as early as September, the report noted.

Shared Health launched a hiring campaign on Oct. 19. Chief nursing officer Lanette Siragusa said nursing and health-care aide resources were urgently needed at care homes.

On Nov. 3, the province officially asked for federal support through the Canadian Red Cross, nearly three weeks after Revera wrote the WRHA to ask it to connect with the humanitarian organization ahead of future outbreaks.

Following the crisis on Nov. 6, WRHA chief health operations officer Gina Trinidad told a news conference that they did not anticipate the huge hit the outbreak at Maples would have on staffing.

“That planning, I will be the first to say, could certainly have been improved in terms of preparing our staffing resources to manage this,” Trinidad said.

Stevenson also determined the province and the WRHA did not have mechanisms in place to immediately redeploy workers to nursing homes in acute need, as was the case at Maples.

Sinha said such plans should have been established well in advance of the second wave of COVID-19 and Manitoba didn’t make appropriate preparations to support homes in crisis.

“Manitoba just had to look over the border in Ontario, where you saw hundreds of homes in outbreak and collapsing that made the news,” he said. “The fact that the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority hadn’t actually organized and created that (staffing) pool and anticipated that, that’s on them.”

“It was only weeks later, when virtually every home in Winnipeg was in outbreak that all of a sudden hospital staffing resources, home care resources, and paramedics were being made available,” he said.

Manitoba’s top doctor, Brent Roussin, said Friday that although the province’s incident command structure — which he leads with Siragusa — was not active as Maples struggled under the weight of the pandemic, it did not specifically affect the crisis response.

Incident command was reinstated on Oct. 30 after standing down for the summer.

“I think that report shows just the challenge when that virus is introduced into a facility like this,” Roussin said. “You’re, of course, going to have the devastating effects on the clients, who are very vulnerable and we saw that, and it has many effects on the staffing shortage.”

The outbreak ended on Jan. 12. A total of 231 people were infected, including 157 residents and 74 staff. Fifty-six residents died.

Friesen was shuffled out as health minister and replaced by Heather Stefanson on Jan. 5.

danielle.dasilva@freepress.mb.ca