Black bears and grizzlies and polar bears… Oh, my! Changing climate bringing different species closer together -- very close, in the case of the grolar -- and experts say polar bears likely to be the losers

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/10/2020 (1864 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was 1998 when Doug Clark came across his first grizzly bear in northern Manitoba when he was working as a park warden in Wapusk National Park.

“And it was kind of a big deal,” he recalls.

What could have been an innocuous day in the field turned into a day that cemented his connection to the brown bears and understanding more about their presence in the region.

“Local people started telling me things,” he says.

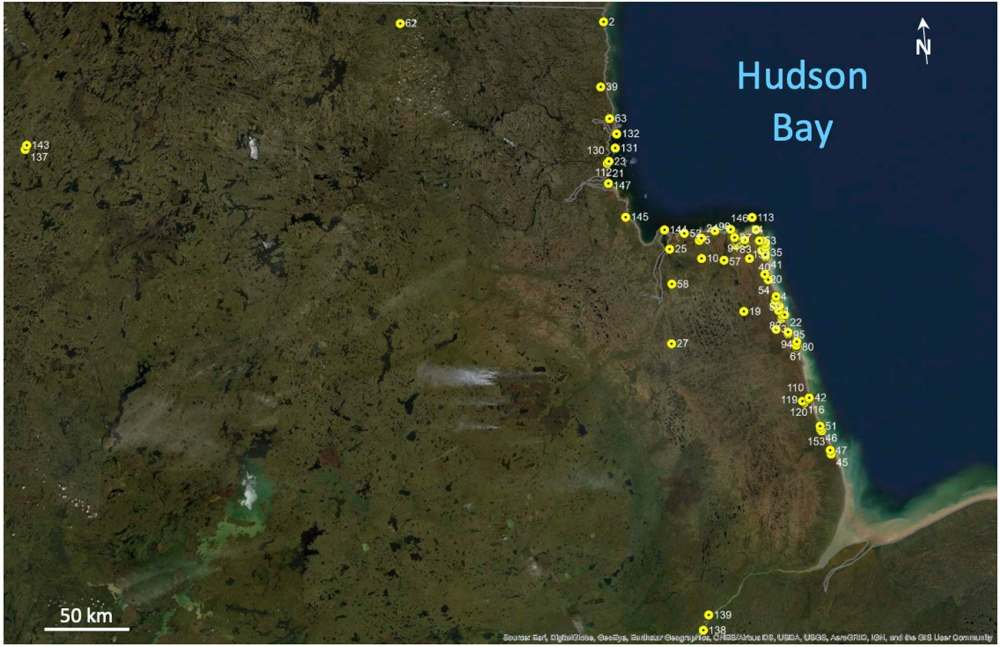

As he started compiling the sightings from residents and other researchers, he was blown away. More than 150 reports over the last 30 years, with observations doubling every decade from the 1980s onward.

“They were probably always there but in very, very low numbers,” says Clark, who is now an associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s school of environment and sustainability.

Records from Hudson’s Bay Co. and oral histories from various Indigenous communities show that the history of the animal in northern Manitoba is long, but sparse, with sightings mostly localized to the northwestern part of the province.

The warming climate has allowed the animals to dramatically expand their range towards the southeast, all the way down to the Nelson River.

“Grizzlies have been observed eating waterfowl and their eggs, as well as feeding on sub-adult polar bears and a beluga whale carcass. Since grizzlies are opportunistic omnivores, there are numerous other potential food sources available to them in these three ecozones,” Clark wrote in a report titled The State of Knowledge About Grizzly Bears in Northern Manitoba recently submitted to the Canadian Wildlife Service.

But even though grizzlies are consistently seen in the province, they remain categorized in Manitoba as an “extirpated species.” Extirpated, or locally extinct, means that a species no longer exists in a given geographic area.

“All of the confirmed observations are of lone bears. There are no confirmed observations of family groups or moms with cubs. And the reason that I say ‘confirmed’ is because Manitoba considers grizzlies extirpated and will still consider them extirpated no matter how many lone bears get seen — until there’s evidence of reproduction in the province,” Clark says.

Clark has heard many stories of sightings of family groups of grizzlies, but the reports haven’t met the threshold for confirmation. The increased scrutiny of reports makes sense from the province’s perspective, he says, because if the grizzlies became endangered — as they would if reproduction in the province was established — instead of extirpated, that would trigger a great deal of provincial responsibility.

So every year, he waits with bated breath as he combs through camera footage hoping to see a grizzly with cubs trotting behind.

“It hasn’t happened yet, but that would be probably about as exciting as seeing an unmistakable polar-grizzly hybrid,” he says.

That’s right, grolar bears.

Instances of the hybrid species have been documented both in captivity and in the wild. The first wild hybrid was found in the Northwest Territories in 2006.

Because of the evolutionary proximity of the two species, they are able to mate. As polar bears spend more time on land because of sea ice melt, and grizzlies expand their range northward because of the changing climate, contact will become more common.

A kill of a particularly destructive grolar in the Northwest Territories in 2010 demonstrated that unlike some other hybrid species, such as mules that are unable to reproduce to a second generation, grolar bears might be fertile.

The bear killed there was sent for genetic testing and the mother of the bear was a grolar bear (half-polar, half-grizzly) while the father was a full grizzly. It was the first known case of a second-generation grolar.

A paper in 2016 traced the genetic heritage of this bear, as well as three other second-generation bears, and found that what appeared to be a spate of hybridization in Canada’s North was, in fact, a bizarre genetic phenomenon and all of the animals could be traced back to one female polar bear and two male grizzlies. The female offspring then mated with their father, creating the second-generation bears. So it is unclear at this point in time if the animals can procreate outside of this particular instance.

“What appeared at first to be a sudden spate of hybridization is reduced to the unusual mating activities of three non-hybrid parents,” the paper, published in Arctic said.

“While we cannot predict the relevance of these events to the future, existing data from polar bears and grizzly bears indicate that introgression has not been a meaningful feature of the recent history of northern Canadian grizzly bears and polar bears.”

● ● ●

In the winter of 2013-2014, Clark captured images of all three of Canada’s bear species — adding black bears to the mix — in one location within seven months of each other. The wildlife camera was mounted about 100 kilometres southeast of Churchill in Wapusk. While area residents had told him all three bears were present in the area, that overlap had never been scientifically documented.

“So it is cool, but why it’s important is because it forces us to confront our own ideas and assumptions about environmental change.”

The changes occurring in a national park forces a reconsideration of what conservation looks like, because the original ethos is to try to keep things the same, Clark says. But stopping these changes doesn’t make sense.

“Are all environmental changes necessarily bad? Frankly, I don’t think so,” he says.

LeeAnn Fishback, a resource conservation manager with Parks Canada based in Churchill, says the result is a “nature-based approach” to conservation.

“Ecosystems are going to change, but maintaining healthy ecosystems as that happens is also very important,” she says. “So climate change becomes an important part of what we do here.”

Considering how grizzly populations have been beaten up in the South, Clark says if the appearance north is a result of climate change, it could be considered a small win amid all of the losses for other species.

It’s important to understand, however, that while grizzlies might be doing well in the subarctic landscape, that does not mean that polar bears, adapted for the marine ecosystem, will be able to survive on land, says Andrew Derocher, a professor of biological science at the University of Alberta.

“From an ecological perspective, there’s this basic idea in ecology that no two animals will occupy the same ecological space. So we already have an Arctic terrestrial bear, and that is the barren ground grizzly bear,” he says.

The grizzlies living in the area are about half the size of polar bears and can live off the land, as they need far less energy than their white counterparts.

“There’s going to be winners and losers in this climate-change scenario as it plays out. One of the winners is going to be, most likely, Arctic grizzly bears,” he says.

“They’re going to do quite well with the warming climate. It will increase terrestrial productivity, they’ll have a shorter winter. But polar bears just won’t have enough resources on land.”

sarah.lawrynuik@freepress.mb.ca