Opportunity knocks

Candidates of all political stripes doggedly pound the pavement in time-tested but tech-upgraded hunt for votes

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/08/2019 (2303 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Just as he’s done nearly every day since April, David Nickarz is spending his Thursday afternoon knocking on doors in Wolseley, a now-wide open constituency he’s hoping to claim as Manitoba’s first Green party MLA.

Three years ago, Nickarz — a longtime handyman and longer-time eco-activist — was narrowly defeated by NDP incumbent Rob Altemeyer, losing by fewer than 400 votes. But with Altemeyer ceding his candidacy to Lisa Naylor, and with Shandi Strong and Elizabeth Hildebrand running for the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives, respectively, Nickarz knows that the key to victory could be behind each door.

“Door-knocking is 90 per cent of the campaign,” he says.

It may sound archaic, in this era of social media campaigning, robo-calls and rigidly controlled public images, but a conversation on the doorstep clearly still carries a lot of weight for voters and candidates alike.

For as long as political campaigns have been run, candidates have sought ways to connect with constituents, says Alex Marland, a political science professor at Memorial University in St. John’s who specializes in political marketing, political communication and election campaigning.

“Door-knocking is a very humanizing way of finding out what’s on the minds of ordinary people,” Marland says.

The strategy hasn’t been around that long, relatively speaking.

“When the country and the province of Manitoba formed, not everyone had the right to vote,” he says.

It wasn’t until 1917 that some Manitoba women were granted franchise, and not until the 1960s when all Indigenous people received the same right. So, in the early days, knocking on doors was an inefficient means of campaigning. Why knock if nobody inside could cast a ballot?

In the 1878 federal election, John A. Macdonald relied on what he called a “campaign picnic” to drum up support. “Put on a good show — a brass band, a hefty cold chicken and ham meal in the park, provide handshakes for the faithful and jokes for the rustics — and the town would remember for years,” wrote historian Gordon Donaldson. This strategy enticed undecided voters to swarm Macdonald; an olden-day equivalent to unions handing out pizza on a boulevard.

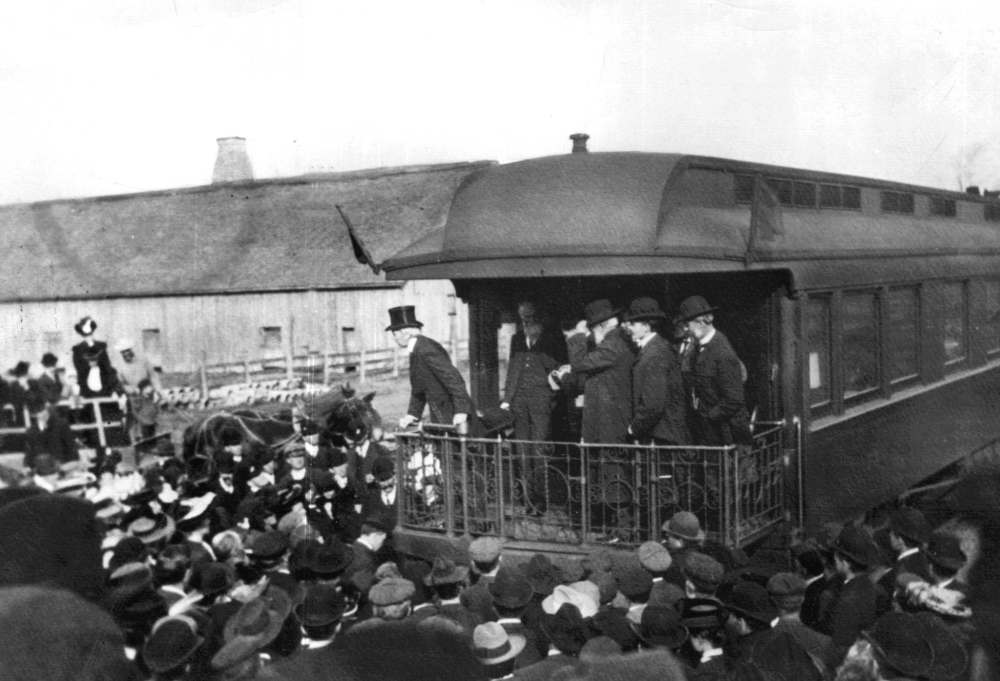

The picnic gave way to “whistle-stop” tours — brief stump speeches delivered by the party leader as a locomotive shuttled them from town to town — which were especially vital in rural areas. In Macdonald’s day, campaigns were largely co-ordinated from within major urban centres and the train tours were popularized in Canada by Wilfrid Laurier in the 1880s, and in the United States by politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt.

Along with party-supported newspapers, the extensive railway system allowed leaders like Laurier to gain massive exposure for their platforms, wrote Michael Nolan of the University of Western Ontario. Laurier’s lead strategist Israel Tarte estimated that between 1895 and 1896, his boss leveraged these channels to hold up to 300 community meetings and to make contact with nearly 200,000 prospective voters. In 1900, Nolan wrote, Laurier spent the bulk of the campaign on a national train tour, using the rails to build up support in major urban and rural centres. The next year, the first transatlantic radio transmission by Guglielmo Marconi added another dimension to constituent engagement.

“Door-knocking is a very humanizing way of finding out what’s on the minds of ordinary people.”

– Political science professor Alex Marland

While it’s difficult to pinpoint an exact origin for the mass reliance on doorstep canvassing, Marland, who won the 2016 Donner Prize for best public policy book, said it generally occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. A 1958 Free Press article says federal Liberal candidate H. Charles Avery relied on his own “private political machine” in his Winnipeg South campaign: his wife, Isabelle, and twin sons James and Charles, 16, went knocking every night from 7 until 9:30.

“My father is running as a Liberal candidate,” the twins would say. “And I’d like you to vote for him.” (Avery lost to Progressive Conservative Gordon Campbell Chown).

In addition to providing constituents with their candidate’s ear and vice-versa, door-to-door canvassing also serves a second, less overt purpose: data collection.

“Every party is collecting info about every elector,” Marland says. “Political parties have huge incentive structures to work on databases.”

Through canvassing, and through online engagement, Marland says parties develop elector profiles, allowing them to customize interactions and target their messaging. If someone raises concerns about hospital closures, for example, the party can develop a customized messaging strategy for that voter and others who feel the same way.

As Nickarz sets out Thursday, a campaign volunteer gets him up to speed on houses with both decided and undecided voters, and continually updates the elector information. A woman who says she usually supports the Greens federally and provincially is switched from “undecided” to “leaning Green.”

From time to time, the team asks residents if they wish to display a candidate sign in their yard and record their responses.

Even as new engagement methods — such as live-video streams or “telephone town halls,” the latter of which the Tories say has connected them with 30,000 Manitobans this campaign — come into play, canvassing has remained a key factor in co-ordinating party messaging, Marland says. Though candidates generally avoid making promises on the front porch, they often offer non-binding but encouraging messages.

“Saying ‘I’ll fight for you and make sure your voice is heard’ is different than promising to get a bridge fixed,” he says. “A candidate can’t do that, unless it’s in the party platform.”

This is an example of party message discipline, or aligning candidates’ messages with those of their party leaders.

“The candidate is essentially acting as a sales rep for the party,” Marland says, adding in most cases the candidates use the interaction to share their party platform and encourage future involvement beyond casting a ballot.

Of course, strategies for connection differ widely between urban and rural settings. In 2003, Leanne Rowat lived in Inglis, a town about 400 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, and ran as a Progressive Conservative candidate in what was then western Manitoba’s Minnedosa riding, an area comprised of 22 municipalities.

“The geographical challenges are that there are several communities, as far as an hour apart, each with distinct concerns from infrastructure, to social services, to health care,” Rowat tells the Free Press. “Obviously, you aren’t going to get to every farm site.”

Nobody can say she didn’t try.

In 2003, the NDP had identified the riding — now called Riding Mountain — as a major focus, and premier Gary Doer made seven separate visits throughout the campaign. So Rowat woke up every morning for a month and drove to a different municipality each day, setting up a placard with her whereabouts and contact information on main thoroughfares.

“(In rural communities) you have to tell everyone you’re there,” she says, lest the trip go to waste. She’d go door-knocking all morning, and then hold court at a local coffee shop or lunch spot. Then, she’d door-knock again.

“I really had to fight hard to be visible.”

All her tireless canvassing led to about as narrow a victory as a politician can achieve: a mere 12 votes put her past the NDP’s Harvey Patterson. She says her ground game gave her unique insight into community needs she’d otherwise have missed, and helped shape her future campaigns.

“The main reason I won in 2003 was door-knocking,” says Rowat, who was an MLA until 2016. In retrospect, she says, “I should have done it more.”

Nickarz hopes his pavement-pounding will give him a similar edge, as does the Liberals’ Strong, who gives her opponent a hug as they cross paths on Chestnut Street.

A few minutes earlier, Nickarz’s team approached a house marked “undecided.” A grey-bearded man emerges. “Mark us down and keep moving,” he says with a smile. “We just threw the Liberals out of our yard 15 minutes ago.”

On to the next house.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @benjwaldman

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.