Remote life, rough justice Justice delayed is the reality for many northern Manitobans caught in an overburdened legal system starved for resources

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/04/2019 (2426 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

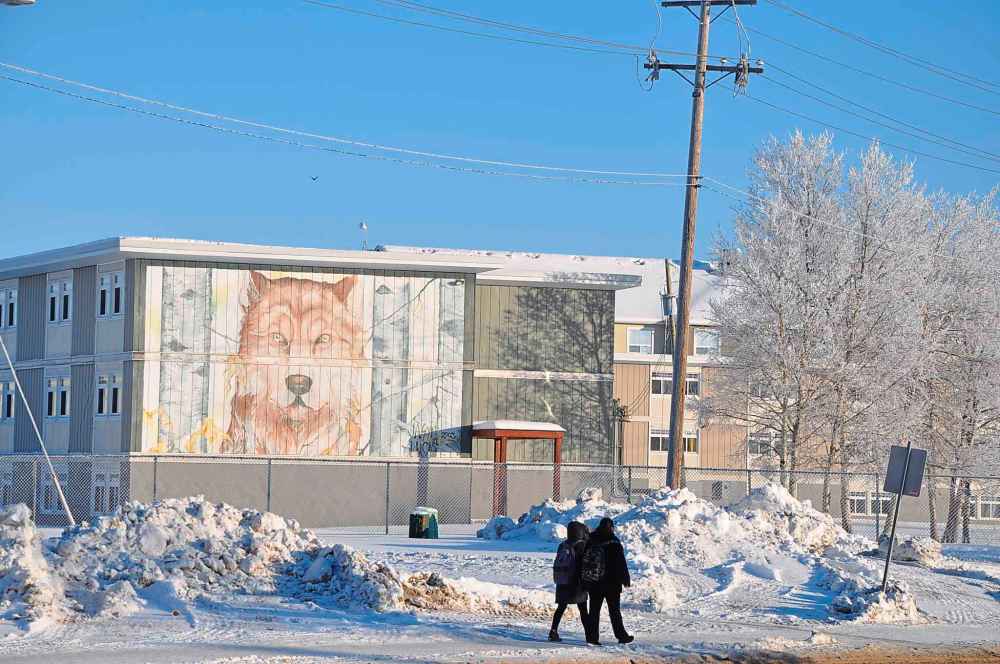

Thompson — In the basement of a government building, a small black-and-white sign points around a corner to Manitoba’s northernmost law courts.

Through an unsecured, 1970s-era lobby that serves as a public waiting room and makeshift lawyer workspace, a set of double wood doors opens into a beige, 48-seat courtroom. Here, atop a wood-panelled dais, a judge is drawing the line.

“I can’t, in good conscience,” Thompson provincial court Judge Todd Rambow said on this Thursday in December.

“As regrettable as it is, I can’t have a further matter proceed before the court,” he continued, looking out at the lawyers and at the courtroom gallery, empty except for sheriff’s officers and one reporter.

His seat overlooks the podiums of an on-duty defence lawyer and a provincial Crown attorney — who aired her exasperation 30 minutes earlier when the clock ticked past 5 p.m. and Rambow asked if they could work late.

“I’ve had a really long week. I’m at my end’s wit,” the Crown said.

Two court clerks, already resigned to the approaching hours of overtime — “We’ll be here quite late doing paperwork anyway,” one told the judge — exchanged hesitant glances and agreed to press on. But now it’s almost 5:30, and Rambow is faced with presiding over a contested bail hearing.

Sheriff’s officers then ushered a 27-year-old man into the prisoner’s box for his first court appearance on two counts of assault and a breach of probation. He’d been in RCMP cells for two days and wanted to apply for bail. Instead, he got an apology from the judge. It’s too late in the day.

Although the man doesn’t consent to the delay — “so noted,” Rambow responded when a Legal Aid articling student pointed that out for the record — his case is bumped to the next bail docket, four days away. The sheriffs will have to drive him 400 kilometres southwest to the nearest jail, in The Pas, and he’ll be first in line to make an appearance by video when Thompson’s in-custody court resumes Monday afternoon.

By the time he gets his first chance to hear any details of the prosecution’s case against him and ask a judge to release him, the man will have spent seven days in jail.

“I always agonize over these situations, because I don’t want anybody to not have their bail hearing in a timely fashion, but the simple fact is, I just can’t do it today,” Rambow said.

This is the norm in northern Manitoba, where the justice system struggles to uphold rights most Canadians would take for granted. Overwhelming poverty, addiction and intergenerational trauma feed into some of the highest violent-crime rates in the country. Court sessions are often snowed under — figuratively and literally — by the task of delivering justice across vast geography with grossly inadequate resources. And systemic racism thrives.

Thompson, the largest city in northern Manitoba, is also the judicial centre of the North. Its basement court office is the hub for anyone arrested within a 400-kilometre radius. Its judges, lawyers and court staff travel to circuit courts in 15 different communities on any given day of the week. There is no jail or remand centre — everyone held in custody has to be shipped to jails located at least four hours south. Timely access to bail hearings is just one of many challenges facing the northern court.

The Free Press is focusing primarily on bail-related problems in the first of a three-part series looking at access to justice in northern Manitoba.

In remote communities, it’s common for people who’ve been arrested to wait anywhere from a few days to a week before they get a chance to ask a judge to release them on bail. It’s a right that can be exercised seven days a week in Winnipeg, but only 2 1/2 days a week for anyone arrested in Manitoba’s northernmost communities.

After their arrest, they’ll be offered perfunctory phone calls with an on-duty lawyer and a justice of the peace, and they’ll be advised to wait until they see a judge to apply for bail. In order to do that, they all have to be flown or driven to Thompson, where bail hearings take place Monday afternoons and Tuesdays and Thursdays, alongside all kinds of other in-custody cases squeezed onto the same docket.

The right not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause is enshrined in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Under federal law, bail hearings must occur within 24 hours after arrest, but the Criminal Code says if a judge or justice of the peace is not available within 24 hours, the accused must see one “as soon as possible.” In northern Manitoba, lawyers say, timely bail hearings are the exception, not the rule.

The denial of timely bail and other systemic rights abuses on display in northern courts have caught the attention of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, which has vowed to take legal action against what it calls the “unconstitutional design” of northern courts in Manitoba and other provinces.

“The problem is that literally innocent people who have not been tried are spending time in jail in a way that should never happen,” Michael Bryant, the Toronto-based executive director of the CCLA, told the Free Press.

“The constitution applies everywhere in Canada, and the remote communities need to tailor their bail system to the constitution, not to their fiscal challenges.”

● ● ●

Over the course of a week in Thompson in December, the Free Press observed in-custody court sessions in the three-courtroom basement facility that serves as the judicial centre of the North and deals with a per capita caseload roughly 14 times the size of Winnipeg’s provincial court.

During those court sessions, people charged with crimes who were there to apply for bail regularly ran out of time. The majority of successful bail applications were cases in which the Crown agreed the accused should be released, raising questions about why they were held in custody in the first place.

Even after release had been granted, some people had to wait in jail because they either couldn’t afford the court-ordered cash bail or they didn’t have anyone who could travel to pick them up. A youth had to be taken into care of a child-welfare agency in order to be released back to his home community, because no adult could travel to court to get him. Or the docket was simply too long to get to everyone, even though family members were present to sign on as sureties.

In other cases observed by the Free Press, some accused had their next court dates set weeks away on the first appearance, as per court policy, while a man pleaded guilty to a criminal breach charge because he couldn’t afford the plane ticket required to get to a previous court appearance.

In one case, a Winnipeg Court of Queen’s Bench judge crafted a sentence specifically so a man would be kept in jail “through the very darkest, dreariest days” of winter that awaited him at home in a remote First Nations community. In other cases, judges tasked with protecting victims in small communities ordered offenders to live elsewhere.

Sentence targets ‘darkness’

Sandwiched between two sheriffs, he kept his head down, looking toward his leg irons and black running shoes. The courtroom, decorated with bright blue paint, bold orange chairs and beige carpet, was small enough that they all sat sideways, shoulders facing the front of the room as the Winnipeg judge spoke.

Sandwiched between two sheriffs, he kept his head down, looking toward his leg irons and black running shoes. The courtroom, decorated with bright blue paint, bold orange chairs and beige carpet, was small enough that they all sat sideways, shoulders facing the front of the room as the Winnipeg judge spoke.

Desmond Osborne, 42, was found guilty in spring 2018 of drunkenly raping a woman on a porch after a party that featured too much homebrew. He’d switched off the exterior light so no one could see them, so no one would stop him. At his trial, the alcoholic since childhood testified his perception of consent was different after he’d been drinking. He was convicted of sexual assault, and on a Monday morning in December, he’d been brought in to one of Thompson’s three courtrooms to find out what his punishment would be.

Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Sheldon Lanchbery told him he’d been thinking a lot about the sentence he’d impose. Osborne had already spent a year-and-a-half in jail — with time-and-a-half credit, it worked out to almost 2 1/2 years. The Crown asked for a 3 1/2-year sentence, and his defence lawyer countered with a request for a maximum of 30 months, saying Osborne had been a “model inmate” while in jail, and requested that he be placed on probation going forward.

After hearing arguments from both lawyers, Lanchbery asked a question. “Is there any point,” he wondered out loud, in sending Osborne back to his home in Shamattawa, a remote fly-in community of about 1,000 in northern Manitoba, at this time of year, when it is “dark and cold” and there’s not much to do?

Deciding against it, Lanchbery came up with a sentence designed to keep Osborne, a Cree man, behind bars during the winter. Instead of ordering a specific number of days in jail going forward, Lanchbery worked backwards from the date he had already decided Osborne should be released: March 15, in time for spring.

“As you heard me say, I’m doing that to keep you in through the very darkest, dreariest days that Shamattawa has to offer, and so that you may be out in time to participate in the caribou hunt. As well, I’m doing that so that you can plan to be out on a very specific day. You can take steps to ensure there are people in Shamattawa on your release that are not going to be those people who drag you into their circumstances, but people who will support you,” Lanchbery told Osborne.

As he imposed a sentence that suggested jail would be preferable to spending winter in an isolated First Nations community, Lanchbery told Osborne he understood the traumatic effects of colonization, residential schools and Osborne’s own family history of abuse, neglect and drug addiction.

“Although the white man such as myself can speak of reconciliation, it is not ours to give. It is ours only to offer. We must be seen as being cognizant of our responsibilities, but it will be for the Indigenous community to tell the white man, tell me, if we are successful in our offerings,” he said.

“Cree people are honourable people. Their heritage is wonderful and rich. When you don’t follow the teachings of the Cree people, just like the white man who doesn’t follow the Christian teachings, gets themselves in trouble. There’s a baseline there that’s important for you to consider.”

— Katie May

Some of the very same practices were examined during Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry 28 years ago, only to be raised and brushed off many times since.

As the provincial government undergoes an internal review of courts on its northern circuit, promises technology upgrades and pushes for greater “efficiency,” according to Manitoba’s justice minister, it appears a group of northern lawyers has had enough. They have signed on to a charter challenge that awaits a hearing in the Court of Queen’s Bench this spring. A desperate and ongoing lack of resources for the North is their common refrain.

“Under-resourcing leads to miscarriages of justice,” said Thompson defence lawyer Meagan Jemmett.

“I think the individual people in the system are, by and large, really disturbed by the things that they see happen. It’s just a resource issue.”

Despite decades of pleading for help to fix a broken system — via internal court committees, meetings with government officials, requests for a stand-alone bail court and even higher-court rulings decrying practices that stack the system against people who are already marginalized — very little has changed in northern Manitoba.

The chronically overburdened and understaffed provincial court office in Thompson has seen people spend a month or more behind bars before they get a meaningful court appearance, having had little, if any, contact with lawyers, their families or the outside world.

Though less common, those cases have become cautionary examples of what happens when people who haven’t been proven guilty get lost in the justice system. The phrase “falling through the cracks” is repeated over and over when northern judges and lawyers talk about extreme cases on the official court record. They’ve been left to wonder whether anyone is listening, whether anyone in the south even cares.

● ● ●

In an unprecedented move, 10 lawyers who have worked in Thompson are lending their names to a constitutional challenge that calls for criminal charges to be dropped in two cases because the accused couldn’t get timely bail hearings.

“As a Crown attorney in Thompson between June of 2014 and June of 2017, I witnessed thousands of accused be practically denied the right to reasonable bail due to this crippling lack of resources,” Jacqueline Halliburn wrote in her affidavit.

Busy days

The day-to-day operation of the criminal justice system in northern Manitoba depends on relatively new lawyers.

Of the 27 lawyers practising in Thompson, 12 of them were called to the bar within the past five years. Two articling students for Legal Aid Manitoba regularly take on duty counsel duties for that office, which, along with the Crown’s office, has seen high turnover and problems with keeping staff in recent years.

The day-to-day operation of the criminal justice system in northern Manitoba depends on relatively new lawyers.

Of the 27 lawyers practising in Thompson, 12 of them were called to the bar within the past five years. Two articling students for Legal Aid Manitoba regularly take on duty counsel duties for that office, which, along with the Crown’s office, has seen high turnover and problems with keeping staff in recent years.

Many of the junior lawyers who spoke to the Free Press said working in the north gave them the chance to get much more experience on serious criminal cases than they would if they started their careers in an urban area.

Concerns “that they needed a little bit more help” made their way to the Law Society of Manitoba, which has started a volunteer mentorship program, says Winnipeg lawyer Roberta Campbell, who served on the Law Society committee that came up with the idea. She is one of five Winnipeg lawyers who signed on in December. They distributed their cell phone numbers to northern defence lawyers and encouraged them to call.

“They are junior, and they face some serious issues in the North. They certainly need some guidance on how to deal with some of those issues,” says Campbell, who has been a lawyer for 25 years and has worked in the north.

Court dockets in northern Manitoba, she says, are “horrendously busy.”

“When I used to go up to the north regularly, it was astounding the volume that they had to deal with, and now, we’re dealing with that volume with relatively junior lawyers,” Campbell says.

There is a larger concern about a dearth of data on the supply and demand of legal services in Manitoba, says Allison Fenske of the Public Interest Law Centre.

“There is a perception that often, justice depends on where you live or your ability to access justice depends on where you live, and that there are serious geographic disparities in terms of the services that are offered and the services that people have access to,” Fenske says, but there is a lack of standardized data.

To tackle the issue would require more investment in the North, she says.

“When we talk about potential solutions, we can’t focus simply on solving the issue in Winnipeg. We have to look outside of the perimeter, and to look at places where the needs are arguably greater in terms of communities that don’t have the base-level of services that folks in Winnipeg enjoy and are able to access,” Fenske says.

—

A national court ruling could be what’s necessary to force the justice system to improve access to justice in remote communities, a criminologist says.

The Supreme Court could cause a reckoning with bail practices the same way it cracked down on widespread court delays in its 2016 Jordan decision, says Prof. Nicole Myers, a criminologist in the sociology department at Queen’s University who has studied pre-trial detention in Canada.

“Maybe we need a case about rural people and their access to technology and access to bail in a meaningful way… we need a decision that comes from the Supreme Court before we’re going to get to a place where we start taking this as the very real and serious concern that it is,” she said.

“Something needs to be done, because nobody should be denied their bail hearing when they’re ready for it. If the issue is that they’re not ready to proceed, fine. But otherwise, you have the right to have your bail hearing without delay.”

As reverberations from a recent groundbreaking Supreme Court ruling to curtail pre-trial custody make their way to courts across Canada, Myers says it will be interesting to see how the justice system responds.

In late March, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that people who are in jail awaiting their trials must be brought back to court at least every 90 days. The decision aims to stop people from languishing in custody if they have been denied bail or haven’t had a bail hearing while they wait for their charges to be dealt with in court.

— Katie May

Halliburn declined a Free Press request for comment, as did other lawyers reluctant to speak publicly about the challenge. She said the written statement speaks for itself.

In other affidavits filed in court as part of the case, the lawyers draw attention to the court’s systemic failures, including a severe lack of court time for bail hearings, problems with receiving police disclosures, and delays in approving legal aid applications. They point out problems with provincial policies that mandate court proceedings be shut down by 5 p.m. every day and require court dates to be set four weeks away, even on an accused’s first appearance, because the court is too busy to have people appear before a judge in the early stages of their cases.

“In some instances, a lawyer has not yet been assigned to the accused by the remand date,” states a joint affidavit from a group of defence lawyers.

A measure once considered an innovative solution to curb court delays in the North has become another way for people to slip through the cracks while waiting for their cases to be dealt with.

The custody co-ordinator’s docket, as it’s called, has been used in Thompson since April 2013, according to documents obtained by the Free Press. It was designed to be an on-paper parking spot to prevent needless in-person or video appearances that waste valuable court time in the stretched-thin system.

The idea, developed by an internal Justice Innovation committee, is that an accused’s next court date will be set a month down the line so they’ll have time to get a lawyer, who can bring the case back to court anytime. But in some cases, as noted in the affidavit and described by several lawyers who spoke to the Free Press, people weren’t being pulled out of the parking spot and brought back to court — they stayed in jail for weeks.

In recent months, the court has kept a closer eye on that docket, reminding lawyers weekly about clients who are on it. Some northern lawyers said it’s a good system — when it’s working properly. Others described it as a way to push those accused of crimes in the North “out of sight, out of mind.”

“All of us bear a responsibility for ensuring that an individual doesn’t sit in a four-week abyss. It’s just a state of limbo,” said Rohit Gupta, the lawyer at the helm of the constitutional challenge.

“What you tend to find is, after an individual spends a good month in jail, they’re essentially ready to capitulate to any sort of guilty plea that would get them out of there.”

Before he was called to the bar last year, Gupta worked as an articling student in Thompson. He’s looked upon as a “junior nobody,” he said, acknowledging his approach has made him unpopular among some in the legal community.

“Every issue that I started raising, it was essentially, ‘This is the way that things have always been done,’” he said.

The charter challenge is still before the court, and Gupta declined to comment on it. Both of his clients named in the motion no longer face criminal charges; a man from Split Lake was acquitted by a judge and a woman from Norway House had her charges stayed by the Crown.

The systemic issues the challenge brings up are set to be argued in a Court of Queen’s Bench hearing in Thompson next month.

“I’m going to continue on raising issues with respect to bail,” he said. “My hope is that eventually something is going to change.”

● ● ●

On a fall weekend about 18 years ago, a planeload of newly arrested residents from Shamattawa First Nation was flown into Thompson for their first court appearances.

The number of prisoners was more than twice the capacity of RCMP and sheriffs’ cells. Previous complaints about overcrowded conditions in Thompson’s holding cells had already made their way to the provincial government, and those in charge wanted to avoid future grievances.

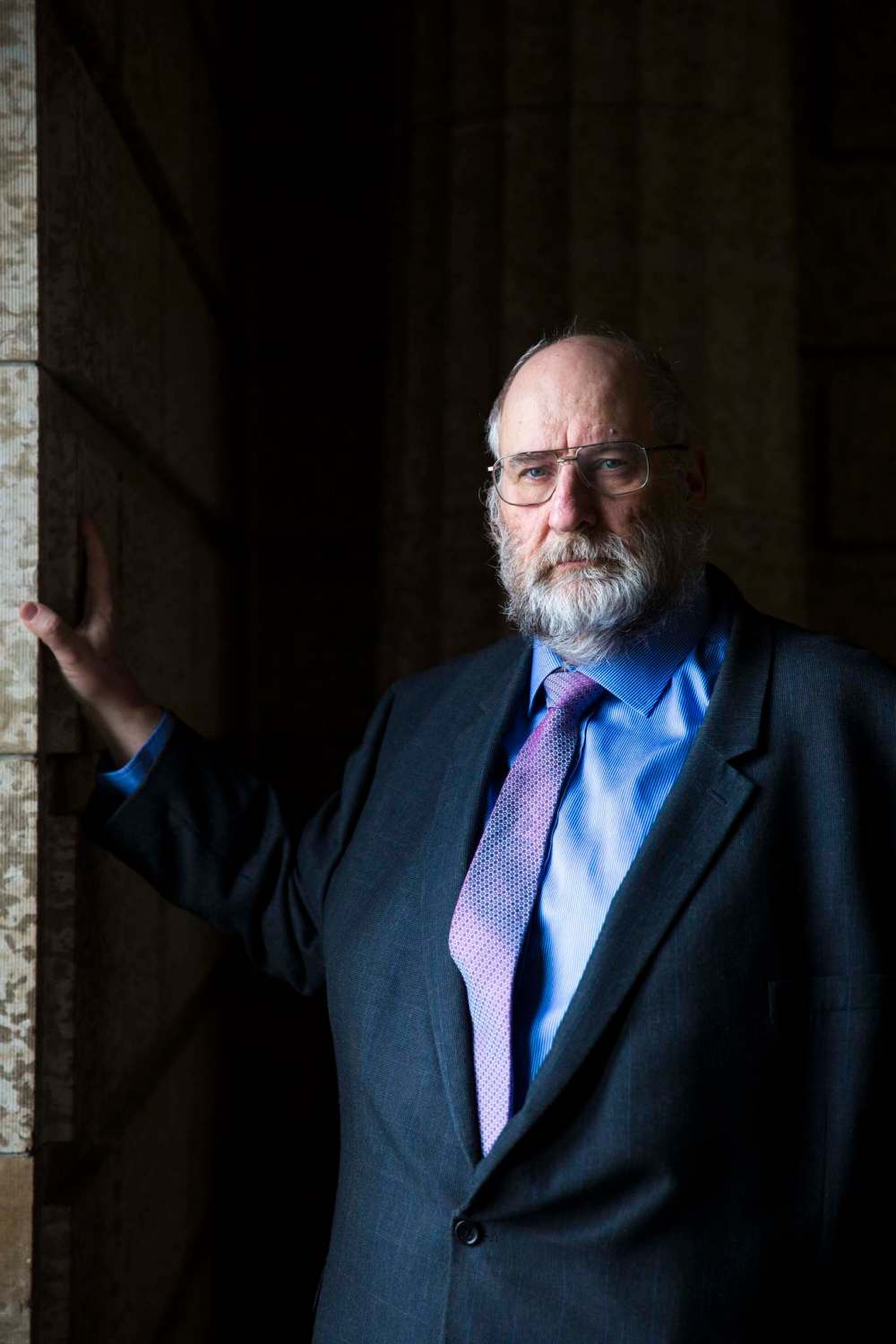

That’s when David Gray’s phone started ringing.

Passed down the chain from a senior official in the provincial attorney general’s office, the message was clear: fix it.

Gray, then the supervising Crown attorney heading up Thompson’s provincial prosecutions office, spent six months working on a plan he figured would save the province a half-million dollars in prisoner transport costs that year.

“I imposed a rule in the Thompson office effective immediately. The sheriffs were instructed by the Crown that absent my permission, we were not opposed to release. That is, there would be no justification for returning them to custody,” Gray said. “The police across the North were told that, and there was some considerable resistance.”

It was a stance aimed at making sure the only people locked up were the ones who really needed to be.

Gray’s vision for the Northern Bail Program would have seen the province hire a bail worker to set up bail plans for people so they wouldn’t have to be detained in custody, cutting down on overcrowding. The work could be done by someone from Legal Aid, or from an Indigenous justice committee, at a fraction of what it costs to ship people from jail to court and back again, he proposed.

It never happened.

Instead, Crown attorneys in the Thompson office worked after hours and on weekends to field calls from RCMP, authorizing the detention of certain individuals and ordering the release of others on certain conditions. Last May, after Gray retired from prosecutions and began practising as a defence lawyer, that work was centralized in Winnipeg.

Now, it’s up to city prosecutors to decide who will stay in jail after they’re arrested in a northern community, even though they may not be familiar with the North or the travel distances required. Some may not realize that being arrested in a remote community often means being locked in an RCMP cell for days before getting a chance to obtain bail.

“Every single Crown I’ve talked to has complained about the fact that their colleagues in Winnipeg have remanded people in custody inappropriately,” Gray said.

Many arrested in the North don’t have family members or friends the court considers qualified to vouch for them as sureties; steady jobs, property ownership and the absence of a criminal record may be required. So some judges have gotten used to ordering people to pay hundreds of dollars in cash before they can be released on bail.

It’s an extra layer of security for the court to try to make sure those who’ve been charged with crimes will show up to court, but it often means people sit in jail on remand unnecessarily — sometimes for months — simply because they can’t scrape the money together.

“When cash bail is ordered, the amount must not be set so high that it effectively amounts to a detention order,” the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 2017.

“The judge is under a positive obligation to inquire into the ability of the accused to pay.”

Unable to pay, forced to stay

“I felt like giving up,” Shayna Kelly-White said over the phone from her placement at Winnipeg’s Elizabeth Fry Society.

“I felt like giving up,” Shayna Kelly-White said over the phone from her placement at Winnipeg’s Elizabeth Fry Society

“I was willing to plead out to these charges — they made me feel like I wasn’t going to get out anyway.”

The 26-year-old spent more than six months in jail after a Crown attorney agreed she could be released on bail. She stayed behind bars only because she couldn’t pay the $500 the court imposed as part of her bail plan. A self-described former drug addict, Kelly-White had an addictions treatment bed waiting for her at Winnipeg’s Behavioural Health Foundation last summer. But a provincial court judge in Thompson wouldn’t agree to release her to the treatment centre and Kelly-White couldn’t raise the cash before her spot was given away.

“I felt like there was nothing I could do. I felt like my life was in their hands and, like, they’re the ones who were saying ‘if you can’t come up with this, then you’re going to stay there,’” she said.

Her case made its way to Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench, where a Winnipeg judge ordered her release in late December 2018 and declared it was illegal to impose cash bail on someone who couldn’t afford to pay. It’s believed to be the first Manitoba court decision that affirms the Supreme Court’s vision for cash bail in Canada.

“When cash bail is ordered, the amount must not be set so high that it effectively amounts to a detention order,” the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in 2017.

“The judge is under a positive obligation to inquire into the ability of the accused to pay.”

Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Jeffrey Harris decided the judge who doubled down on the cash-bail requirement for Kelly-White was wrong to ignore her defence lawyer when he told the court she couldn’t afford $500.

Kelly-White was part of Elizabeth Fry’s bail supervision program when she spoke to the Free Press in February, shortly after Harris released his written reasons in her case. She was awaiting trial on drug charges after she was arrested in Norway House in May 2018. Police pulled over the car she was in and allegedly found 40 rocks of crack cocaine.

Kelly-White said she battled drug addiction for years but had been sober for 10 months and was participating in counselling programs. She said she didn’t want to go back to jail.

“That’s the only thing that runs through my head nowadays, like if I go back in, I’m stuck back in there, and I don’t want to be, because I’ve come so far in being sober and doing these programs and trying to prove a point to my friends that are sitting in there, that there’s more to it than this,” she said.

“That’s my biggest goal in life right now, that I can sit there and look at people and be like, hey, there’s more to than just sitting here and trying to get your next fix all the time. I’ve been at the bottom a lot in my life, but this is probably the lowest I’ve felt right now, how the justice system actually made me feel like that.”

— Katie May

Yet, in northern courts, a class system is part of the everyday process, said Gray, who has recently fought cases on behalf of northern residents who were granted bail but couldn’t get out because they didn’t have enough money.

“People believe that the system isn’t racist. Because it’s true — it didn’t matter to me if the person in front of me was Indigenous or white or a recent immigrant, it didn’t matter. I’d prosecute more or less the same way and I did try to take into account the special circumstances of all of the individual offenders,” he said.

“The people in the system are, for the most part, fair in that sense. But the system is designed in a way that is inherently racist… and will create disparities between non-Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal communities.”

When asked if the government was aware of the long-standing concerns surrounding bail, Justice Minister Cliff Cullen said he knows there are ongoing “challenges” in northern Manitoba.

“We want to make sure that everyone has timely access to justice, particularly in Thompson and northern Manitoba,” he said in an interview with the Free Press after he visited the Thompson court facility for the first time as justice minister earlier this year.

The province is responding by trying to fill vacancies, promising better wireless Internet and video conferencing, pricing out court renovations and looking for ways to “streamline” the prisoner transportation system, he said.

● ● ●

Obtaining timely bail hearings is just one of many problems with access to justice in northern Manitoba, largely stemming from the poverty and isolation of many remote communities and allowed to snowball through the criminal justice system.

“They all come from the same problem of ‘how do you bring justice to a place, what kind of resources do you need to bring the same level of justice that you would get in the city to a remote place?’ And all of the struggles that the system has had creates more problems,” said defence lawyer Chris Sigurdson, who has worked in circuit courts north of Winnipeg for about 20 years.

“The system is stretched thin. Perhaps throwing resources at it may not assist. Certainly, there has to be greater understanding of those problems and more of an awareness of those problems from people in the capital.

“There are people within the system who are trying hard and doing what they can, but they’re doing it on their own. There needs to be more of an overarching direction to it. Because there isn’t a political will to push for it.”

For years, those working in the justice system have complained that the official hub of northern Manitoba doesn’t get its fair share of judges, justices of the peace, court clerks, Crown attorneys, defence lawyers or sheriffs.

Court staff from Winnipeg are routinely sent north to try to make up for shortages, prompting concerns from the provincial government employees’ union. Recruitment and retention of clerks and prosecutors is a priority for the province, Cullen said.

But it’s nothing new. The inadequacy of staffing in Thompson’s court office — and the lack of space in the office itself — has been brought up repeatedly in the provincial court’s own annual reports dating back to 2006.

“We don’t do things the same way as Winnipeg because we can’t do things the same way as Winnipeg, partially because we don’t have the staffing resources,” said Thompson defence lawyer Serena Puranen.

More resources for northern courts was top of mind for Chief Judge Margaret Wiebe when she was heading into her first full year as head of the provincial court.

“For me, focusing on the north is a very big priority. We need to get more judicial resources in the north to be able to deal with matters up there in a more timely way and that is an issue that I’m very focused on,” Wiebe told the Free Press in early 2017.

A Free Press request to interview Wiebe recently was declined with an explanation that she can’t speak publicly about challenges facing northern courts while cases involving those issues are being appealed in Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench.

“The chief judge is open to these discussions at some point down the road, but it (would) not be appropriate at this time,” a court spokeswoman wrote in an email, citing the ongoing legal action.

In sheer numbers, the caseload in Thompson provincial court is second to Winnipeg’s. But Thompson’s population — about 12,500 — is 64 times smaller than the capital’s.

With its three full-time judges and two justices of the peace, Thompson’s provincial court office completed 6,927 cases in 2017-18, according to the most recent provincial court data. In Winnipeg, where there are 40 provincial court judges and 16 justices of the peace, 31,776 cases were completed.

● ● ●

It’s been nearly two years since Joyce McIvor was talking to prisoners over the phone in Thompson’s court office, but she’s been told it still rings for her.

Now, the calls come in on her personal cellphone, or via social-media messages from friends of friends and their families who ask for her tips on navigating the criminal-justice system.

“All the time,” she said.

The Thompson resident has no legal training, but when she worked for Manitoba Justice as an Aboriginal court worker from January 2016 to June 2017, she thought she’d seen it all. Her position — a bridge between Indigenous accused and the justice system — has been vacant since she left.

“I know — not even being in school for law — with the justice system you can see clearly who’s favouring and who’s not being favoured. And why are our people overpopulated in the jails?”

As a Cree woman, she saw the answer was right there in court, day in and day out. She heard it on the other end of the phone line from men in custody on remand who told her they hadn’t been able to contact their lawyer for weeks. Or they couldn’t get out on bail because they didn’t have cash to post. Or they would do anything to get back to their families.

“They would say, ‘Well, I think I’m just going to plead guilty on that just so I can get out of here.’ And I’m going, ‘And then you’re going to have a record! This is going to stay with you! Why do you want to do that?” McIvor said.

The response, too many times, was, “I need to get out!”

“‘I’m sick of it, I need to go home, I need to go home and help my wife or help my girlfriend and the kids,’ that’s what most of them are saying,” she recalled.

When a guilty plea means getting out on time served and waiting for a trial means spending many more months behind bars, it’s easy to see why some people, particularly those who’ve already amassed long criminal records, would think, “what’s one more?” defence lawyer Jemmett said.

“When you’re a criminal lawyer, the No. 1 question that people ask you is ‘how do you represent people who are guilty but want to go to trial?’” she says.

“The far more common ethical problem happens when someone who credibly tells you that they are innocent wants to plead guilty.”

Many people in the north bristle at southerners’ attempts to tell them what to do without putting up the proper support to make it happen. The justice system is no exception — directives from Winnipeg can be met with a raised eyebrow, an eyeroll, a knowing chuckle.

But dozens interviewed agreed: when access to justice varies this much from place to place within Manitoba, it’s everyone’s problem.

“It doesn’t contribute to any sense of fairness, acceptance, respect for the system,” said Puranen. “It only further marginalizes them, fosters disrespect for the system, it gives people grudges and chips on their shoulders. It makes problems worse.”

Next week: Part 2 in Katie May’s series, on transportation challenges

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.