The last Manitoban An estimated 7,000 men and women from this province died in the First World War; Roblin farmer Robert McCrae's life ended only 240 minutes before the fighting did

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/11/2018 (2587 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In a military hospital room in Eastbourne, on the southern coast of England, a Manitoba soldier lies in a hospital bed.

Alone, far from home and family, his lungs are filled with liquid and his breathing is laboured. His skin is blue and he is in pain.

He takes his last breath. A nurse records the date and the time of his death.

His battle has ended but, for a few more hours, another conflict is raging.

It’s 7 a.m., Nov. 11, 1918. Just four hours before the war that he came overseas to fight — the Great War — will come to an end.

On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the soldiers on both sides — who have battled and bled through four miserable years of muddy trenches and bitter cold — will lay down their weapons as the Armistice takes effect.

They will not move their lines any further.

And in all likelihood four hours earlier, 24-year-old Robert McCrae became the last Manitoba soldier to die in the First World War.

● ● ●

Edmonton’s Lynn Gregory — McCrae’s great niece and the granddaughter of Nellie McCrae — explains that family lore says they are related to John McCrae, the author of In Flanders Fields. The records that would prove it were destroyed in a fire years ago.

Gregory doesn’t know anything about Robert McCrae.

“I don’t think I recall my grandmother or my mother ever talking about him,” she says. “I know I did spend, as a young child, a lot of time with my grandmother, but it was so long ago I don’t remember if she said anything.”

Gregory’s daughter, Bonnie Pritchard, says she has been trying to find out more about all of her ancestors — including Robert — and she’s hoping someone out there can give her a hand.

● ● ●

It wasn’t the first time a member of the McCrae family was in Britain. They trace themselves back to Cumnock, a town in East Ayrshire, Scotland.

William McCrae and Mary Hanna Frame — who would become his wife — were both born in Guelph, Ont. in 1852. When they were 18, they married at the community’s St. Andrew’s Church.

Just two years later, according to the family history, the couple left Bruce County and joined a wagon train and headed west to Palestine. The community changed its name to Gladstone in 1882, because the villagers admired the prime minister of Britain, William Ewart Gladstone.

According to the community history book, Gladstone Then and Now, 1871-1982, times were good for the first couple of years, but in 1874, just when farmers believed they were about to bring in “a good crop,” the skies suddenly darkened in the middle of the day. So many grasshoppers descended they “literally covered the earth… our crop simply went down their ravenous maws. For those who had just settled among us the year before, it meant a tough time, but they braced up.

“But the millions of pests had laid their eggs before departing and the second year of 1875 was, if anything, 10 times worse than the other.”

The book said many would have lost their farms if the federal government hadn’t given them seed to plant and taken over the mortgages on their land for repayment.

The grasshoppers came again the following year, but this time their stay was short and the crops suffered little damage.

The family went on to become successful farmers and in the next few years they acquired four quarter sections of land in the area, two of which are now the west and southwest side of Gladstone. By 1907, they had 34 cattle, 12 horses, two pigs and $220 in the bank.

Robert McCrae was born May 17, 1894 into a family that eventually had, including him, 11 children — six daughters and five sons: George, William, John, Henry, Lizzie, Martha, Nellie, Bonnie, Maudie and Annie. Between the 1901 census and the one in 1906 Annie, who was the oldest child and whose last name was Boughton, was back living at home with her 18-month-old son William Jr.

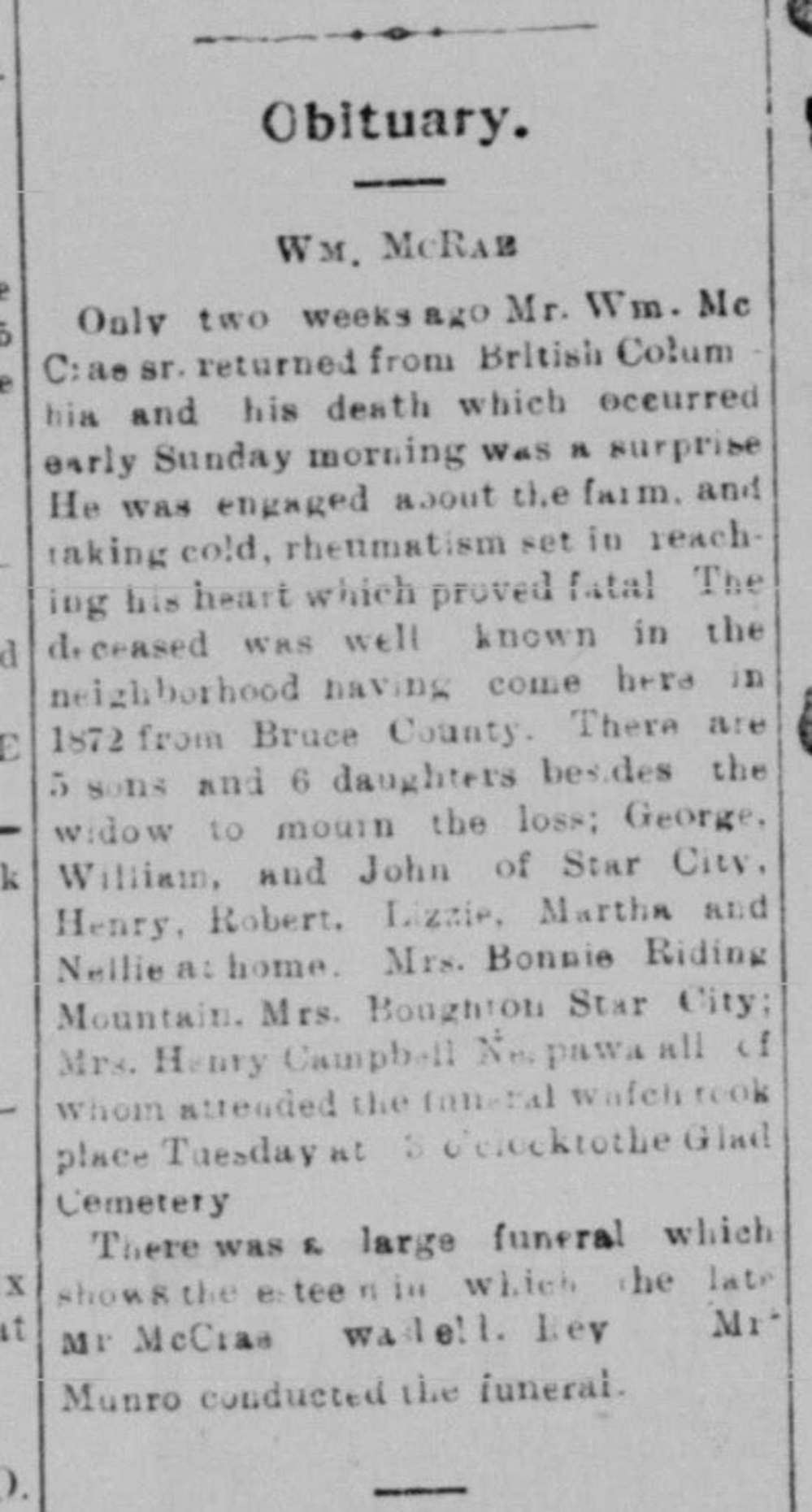

On June 2, 1907, the family’s patriarch, William, died suddenly. He was 59.

His obituary, printed in the Gladstone Age a few days later, called the death “a surprise” and went on to say he had returned two weeks earlier from a trip to British Columbia and had contracted a cold while working on his farm. The obit went on to say the cold “set in, reaching his heart which proved fatal.”

He didn’t leave a will. When the value of the estate was added up, he was worth almost $12,000.

With bills to be paid and the three boys at home just 14, 12 and nine, the Northern Trust Company scheduled an auction for the morning of Nov. 13.

“The whole of the live and dead farming stock, furniture, etc., Comprising: 32 head cattle, 12 horses, pigs, Capital assortment of agricultural implements, harness, etc., etc.

“The whole will be found of an exceedingly useful description and offered for absolute sale.”

His widow Mary never remarried and, perhaps because she learned her lesson when he died without a will, she wrote one for herself in 1933. When she died in Gladstone Dec. 15, 1941, the bulk of her $945 estate went to Nellie Regnier, her daughter living in Delmas, Sask. Daughter Elizabeth Bonney in Kelwood got $1.

McCrae’s family today has no idea why the difference in bequests.

The only other public record of the McCrae family in the years between 1907 and 1916 is from 1910; a document shows that McCrae’s mother received a homestead grant for a piece of property on the west side of Lake Manitoba, just north of Beckville Beach.

● ● ●

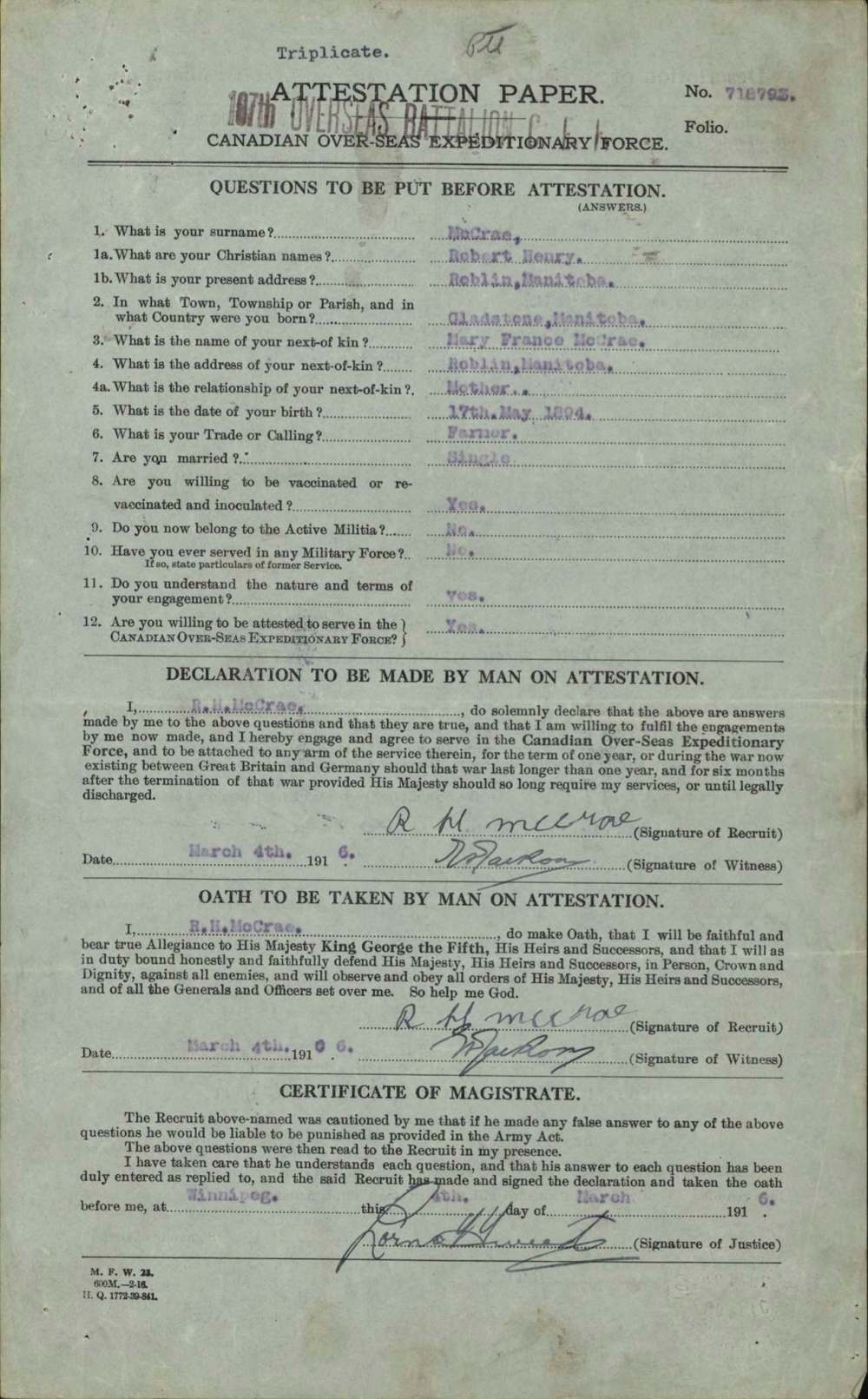

There’s a gap of several years in the public record of Robert McCrae, but by the time he decided to join the Canadian Overseas Expedition Force in Winnipeg on March 4, 1916, he was a farmer in Roblin.

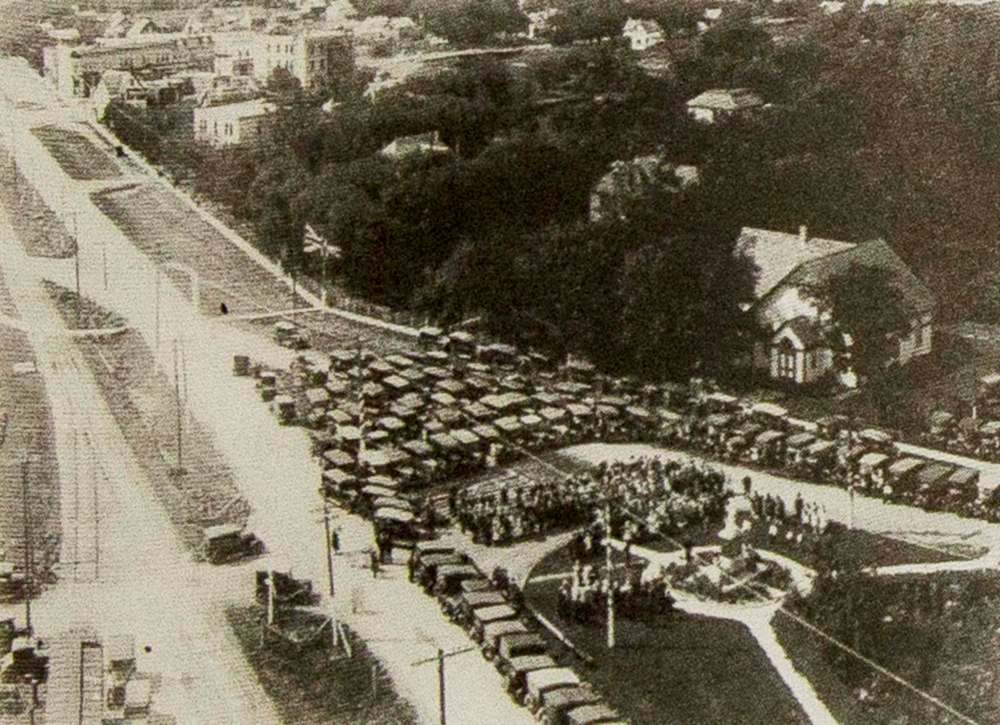

According to local records, McCrae was one of 99 soldiers from the Roblin area who enlisted; 40 didn’t return.

McCrae must not have told his mother his plans because, with some estate documents left over from when his father died, she got a lawyer to track him down a few months later at Camp Sewell, later called Camp Hughes, the First World War training camp next to the present day CFB Shilo near Brandon.

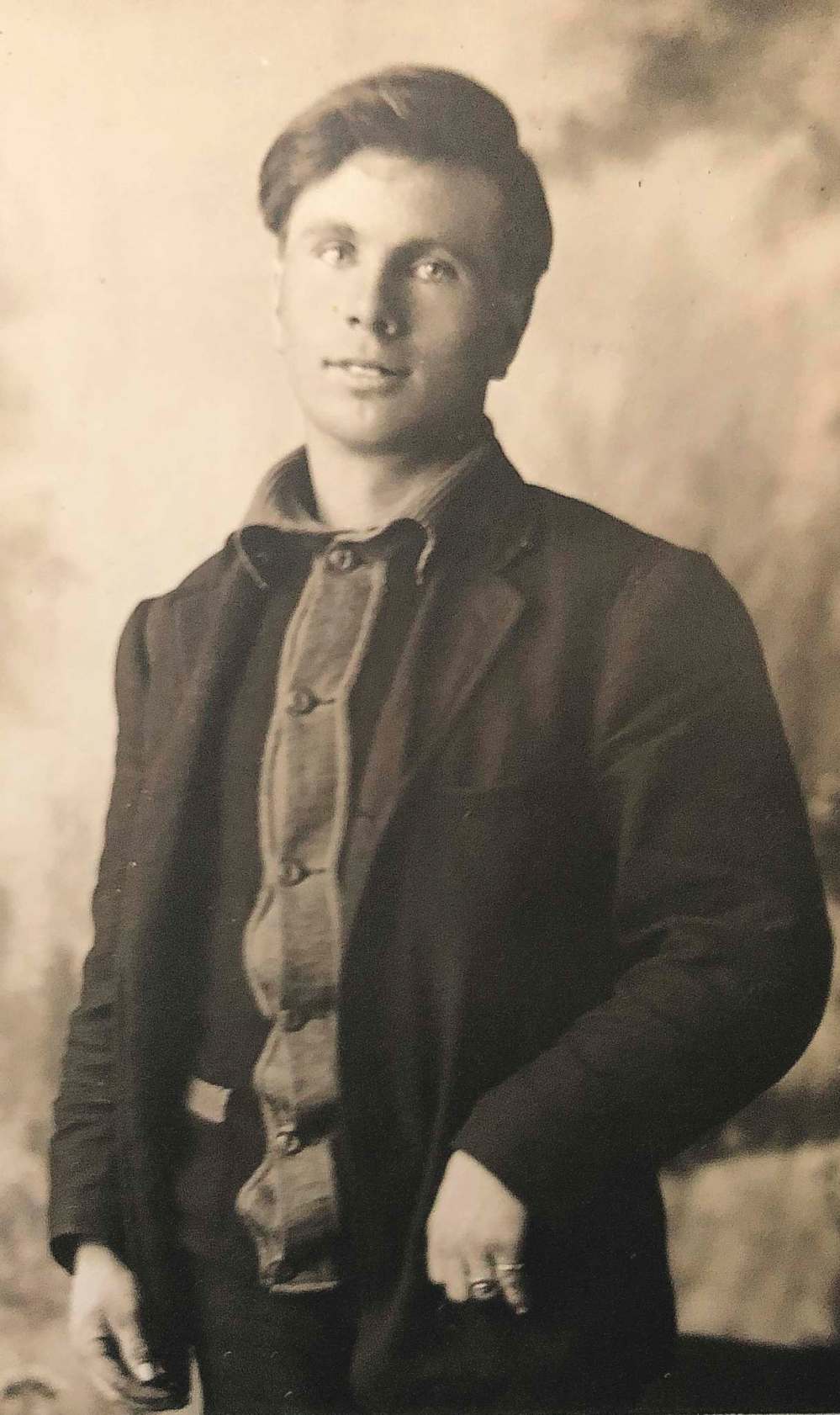

When McCrae the Roblin farmer signed up, becoming 718793 on his Attestation Paper, he was just 21.

He was also single, noted he was Presbyterian, said he would agree to be vaccinated and that he’d never served in the military before. He stood five-foot-eight-and-a-half inches tall and had a fair complexion, blue eyes and dark hair. The only mark noted was a small scar across the first joint on the thumb of his right hand.

McCrae also answered in the affirmative when asked if he “understood the nature and terms of your engagement.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

● ● ●

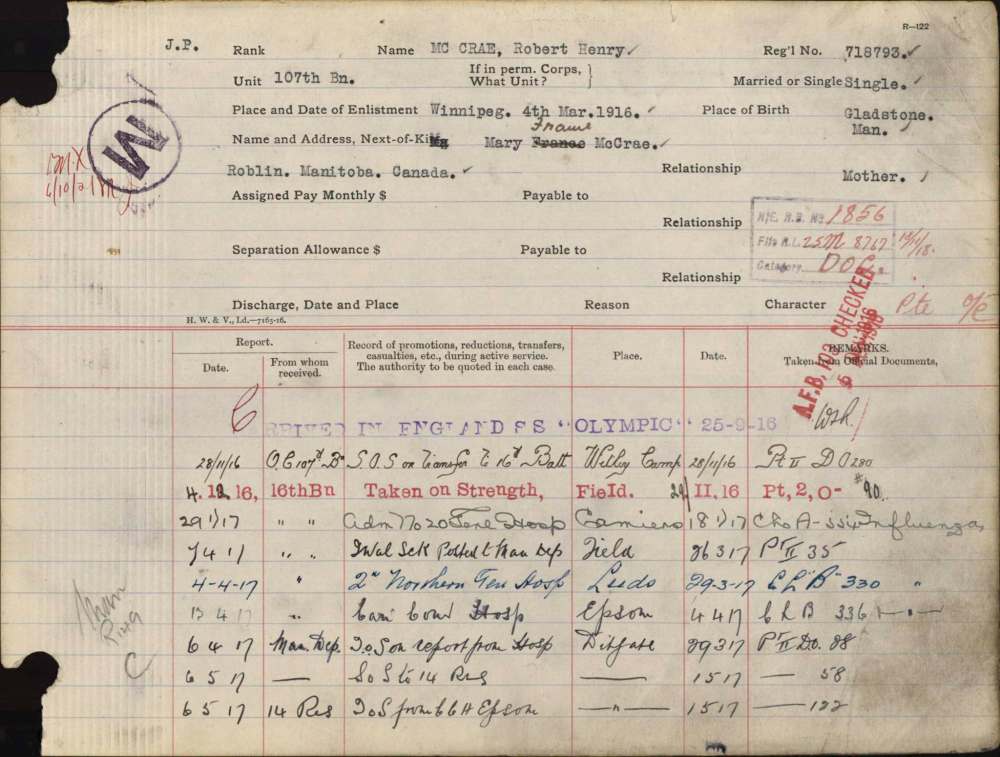

McCrae was assigned to the 107th Battalion. He boarded the Olympic, a sister ship of the Titanic, in Halifax on Sept. 18, 1916 and arrived in Liverpool, England seven days later.

Little more than two months later, when he was in France, McCrae was transferred to the 16th Battalion, also known as the Canadian Scottish, on Dec. 4, 1916.

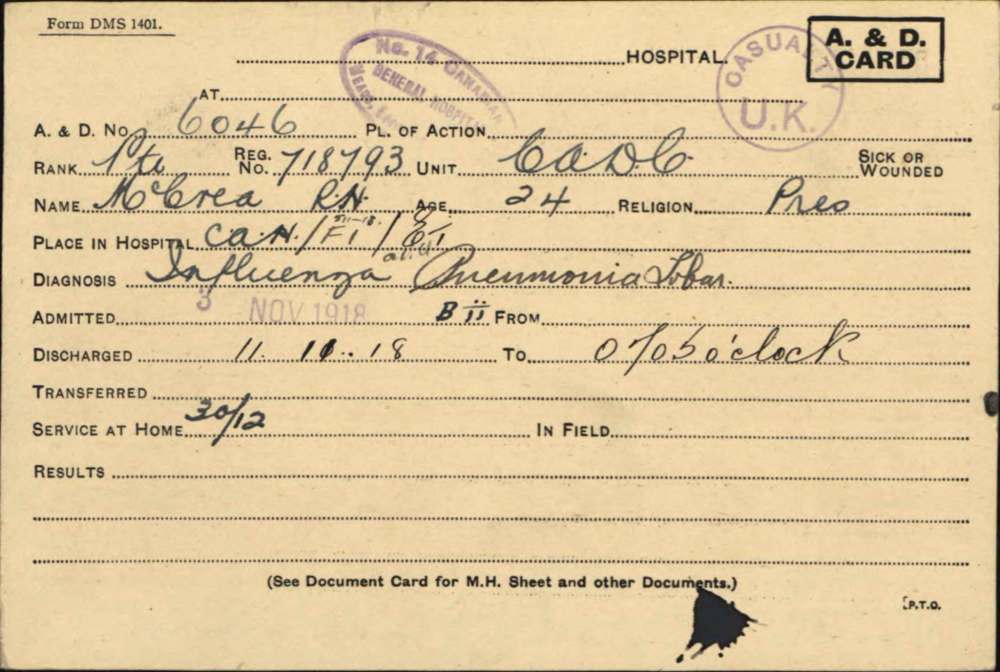

On Jan. 29, he was pulled off the battlefield and admitted to a hospital in Camiers, diagnosed with influenza.

The History of the 16th Battalion in the Great War has clues about what happened.

The book, written in 1922 by H.M. Urquhart, lieutenant-colonel, in the reserve of officers with the Canadian Non-Permanent Active Militia, talks about the conditions the regiment experienced January and February 1917.

“In this period there came the longest spell of cold weather experienced by the Canadians in France,” Urquhart wrote. “Whilst the unit was at Villers au Bois or occupying the trenches on Vimy Ridge the weather had been moderate… but the spell was of short duration.

“On Jan. 21st, the cold snap returned. It increased in intensity until the 23rd, when there was a very heavy fall of snow and from that date until Feb. 16th hard frost, with frequent snowstorms prevailed. The whole landscape was enveloped in a white sheet; the ground was as hard as granite. The men on duty in the front line and on patrol suffered considerably.”

The book says it was so cold that even the water-supply pipes, which came within metres of the front lines, were frozen all the way to the back lines.

Did McCrae catch a cold while in those conditions and it advanced to pneumonia? We’ll never know, but his hospitalization in Camiers began his long stays in various hospitals during his more than two years in the military.

The 16th Battalion, which had already fought at Passchendaele, Ypres, and Somme, went on to fight at Vimy, Arras and Scarpe, among others. Battalion members Lance Corp. William Henry Metcalfe, Lt.-Col. Cyrus Wesley Peck, Pte. William Johnston Milne and Piper James Richardson received Victoria Crosses while McCrae was convalescing in England.

● ● ●

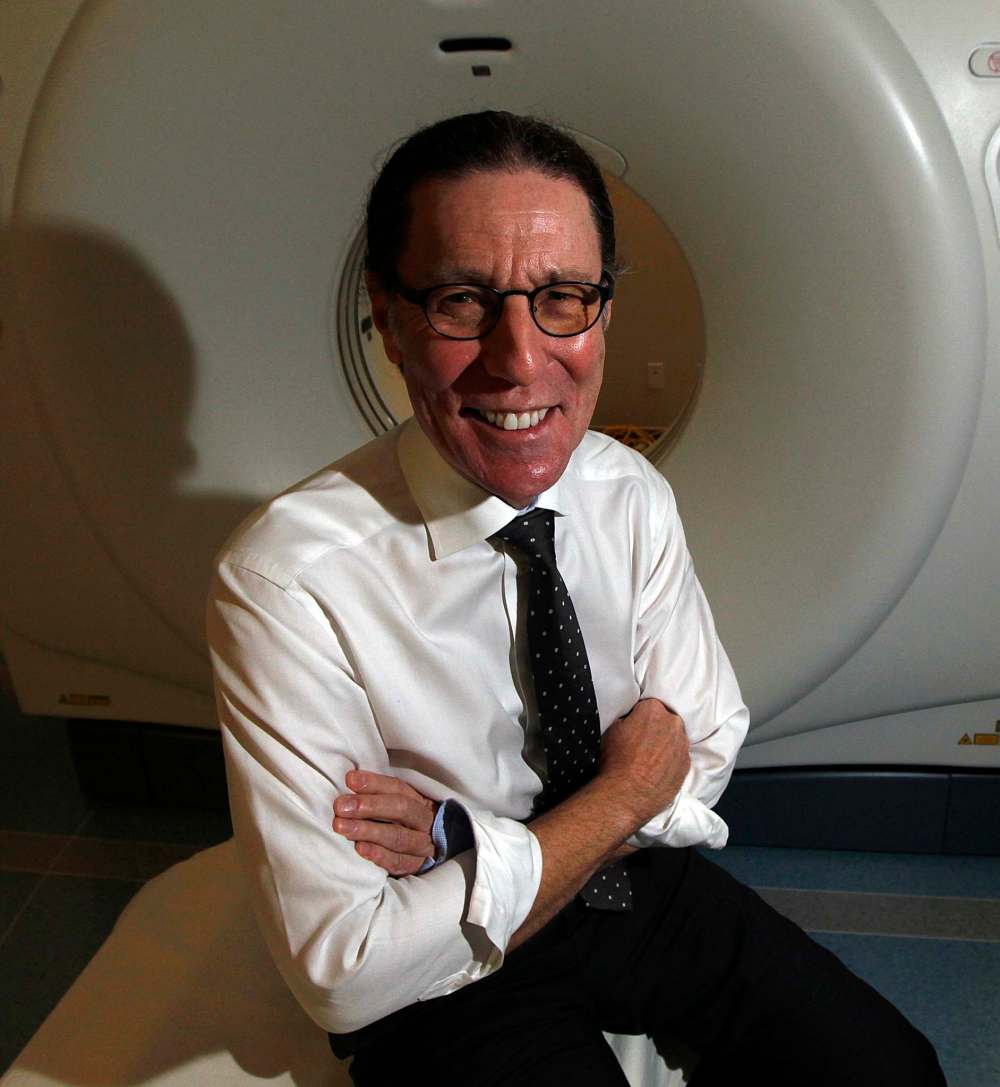

Dan Lindsay, a radiologist in Winnipeg and Selkirk, served five tours of duty as a civilian medical specialist with the Canadian Armed Forces, helping care for troops in Afghanistan. He is also a past-president of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba and he was named the province’s doctor of the year by Doctors Manitoba in 2012.

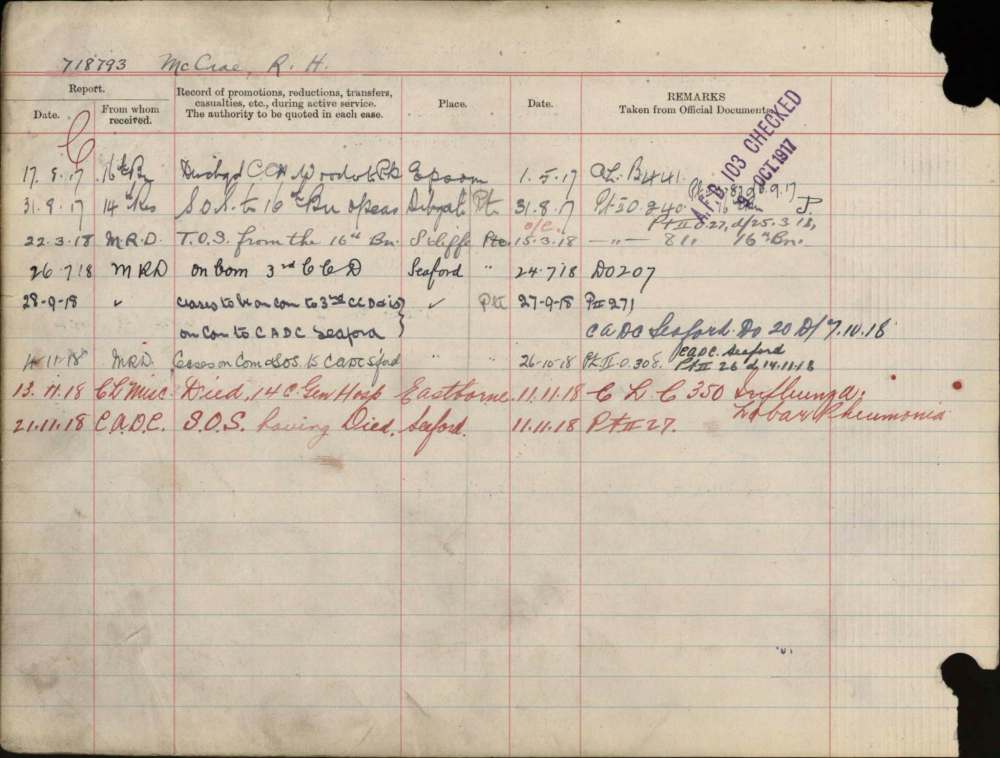

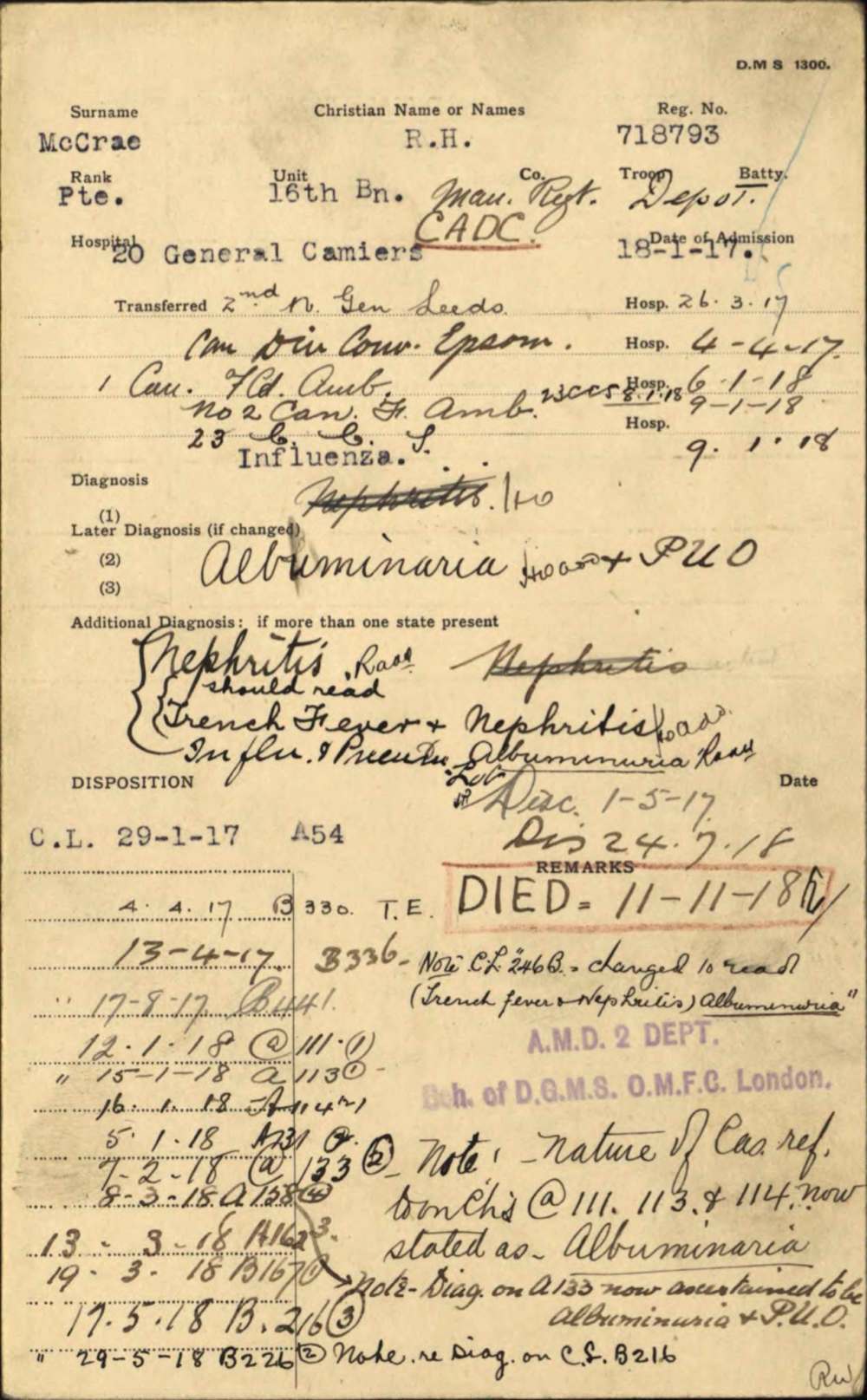

Looking at McCrae’s 1917-18 medical chart recently, Lindsay says the soldier had limited options for survival with the medical technology available at the time.

“The treatment options today include kidney dialysis, heart-lung bypass machines and antibiotics. Antibiotics that save so many lives were not yet available” says Lindsay.

“Today, wounded soldiers who we treated in Afghanistan would have certainly died during the First World War. We were able to treat most of the traumatic injuries and our men and women who served Canada are now back home enjoying productive lives.”

McCrae was diagnosed with influenza in January 1917 at the No. 20 Canadian General Hospital in Camiers. He was lucky this time around. He was sent first to the NGH Leeds on March 29, then the Canadian Division Convalescent Hospital in Woodcote Park, Epsom on April 4 before being discharged on May 1.

McCrae was back serving in the trenches in France when he became sick again. He was diagnosed with nephritis at the No. 1 Canadian Field Ambulance on Jan. 6, 1918. These were the medical teams who served to remove casualties from the front to clearing stations where, if needed, urgent surgeries were done.

Two days later, McCrae was at the No. 23 Casualty Clearing Station and the next day he was transferred to the No. 2 Canadian Field Ambulance with a new diagnosis: “albuminuria and PUO.”

“Albuminuria is an observation,” Lindsay says. “He had protein in the urine, indicating kidney damage that could be the result of many types of illness.

“And PUO was typed wrong; is was probably PUD indicating peptic ulcer disease.”

Lindsay says with PUD it meant the inner lining of McCrae’s stomach was sore and inflamed with ulceration.

It also meant McCrae continued to be on the move. By March 7, he was at the 83rd General Hospital, also known as the Dublin because of the volunteer staff from Irish hospitals, on the coast of the English Channel in Boulogne, France. It had formerly been named the13th Stationary General Hospital.

A week later, on March 15, McCrae was back in England, now at the Boscombe Military Hospital in Bournemouth. This hospital was created when the War Office converted the Royal Victoria and West Hants Hospital to a 200-bed facility to look after sick and wounded soldiers.

Two months later — and almost a year since he had been there recovering from his first bout of pneumonia — McCrae was back in Epsom at the Canadian Convalescent Hospital with his diagnosis now changed to trench fever and nephritis. But, just four weeks later, was transferred to the King’s Canadian Red Cross Convalescent Hospital, a Crown-owned house which the Canadian Red Cross was allowed to use, in Bushey Park, Hampton Hill.

Trench fever is an infectious bacterial disease spread by lice. Its symptoms include high fever and severe headaches and recovery can take weeks.

“You can imagine what they were going through in the trenches with the lice and the lack of sanitation,” Lindsay says.

McCrae was not alone in contracting the disease. It is estimated that between one-fifth to one-third of British soldiers had bouts of trench fever.

As for nephritis, it is an inflammation of the kidneys and is caused by infections and autoimmune disorders.

By June 8, 1918, McCrae was at a Remedial Treatment Gymnasium in Seaford, England, diagnosed with nephritis and experiencing vertigo and back pain. A note in his file says he “looks well.”

McCrae was able to get leave from July 24 to Aug. 5, before returning to continue his rehabilitation. His progress notes on Aug. 13 say he was doing all of his exercises.

But by Oct. 23, he was back in hospital with trench fever.

A couple of weeks later, McCrae was taken to his final stop, the No. 14 Canadian General Hospital in Eastbourne, where, on Nov. 7, he was diagnosed with influenza and pneumonia and described as “dangerously ill.”

He died four days later.

One of the documents in McCrae’s medical file, under remarks, notes in capital letters with a box around it: “DIED 11-11-18”

But Lindsay says it was probably the combination of influenza, pneumonia and kidney disease that ended McCrae’s life.

“He had influenza, but then he got a major medical complication with his kidneys.”

“You get cyanotic when you die — which, simply, means to turn blue. When body fluids build up in your body, all organs are involved, including the lungs. He had influenza, renal failure, too much fluid in his body and probably fluid in the lungs and around the heart. The lungs are like a sponge filled with fluid before he died.

“He ultimately died, probably of multi-organ failure.”

Lindsay says there are many medical procedures that McCrae would have received had he lived 100 years later.

“Today, with the kidney failure, we would treat him with dialysis,” he says. “They couldn’t do dialysis then. We would intubate him to support his breathing. There are so many more medical options available today.

“With a severe flu illness patients can die, but these days we can support people with intubation, intensive-care units and supportive medical techniques. But, if you already have medical conditions such as kidney disease or heart disease, the flu is just one more straw to get you in trouble.”

•••

The public records and interviews with descendants don’t offer a very detailed picture of Robert McCrae.

But Kathleen Epp, a senior archivist at Archives Manitoba, says McCrae is one of many Manitoba soldiers who died during the First World War whose names do not appear on the archives’ partial index.

“You might think you could go by where they enlisted, but many from Saskatchewan enlisted at Camp Hughes in Manitoba so you can’t always go by that,” she says.

“They didn’t keep records together of the provinces they came from… they didn’t think people would want to know something 100 years later.”

The list, which has 1,092 names, was compiled from a “shoebox” they received filled with index cards, she says.

“We think Public Works was trying to assemble a comprehensive list of Manitobans killed in the war,” she says. “We don’t know why they stopped doing it or maybe they were trying to complete it after the war. We really don’t know much about it.”

It’s believed as many as 7,000 Manitoba men and women died in the First World War.

● ● ●

Robert McCrae’s military records contain a mystery.

Among the papers, there is a will, which names his beneficiaries. His mother, who was living near St. Rose du Lac at the time of his death is listed.

So is Miss Hannah Howell of Roblin.

A girlfriend? Someone McCrae met while farming in the Roblin area? A sweetheart back home he planned to marry when he returned? No one knows today, but years after McCrae’s death, in 1933, Howell married Jack Nastrom, from a farm north of Roblin. Nastrom served in both the First and Second World Wars and after the second he and his wife lived on Soldier Settlement Land in the Blue Wing district — named for the nearby Blue Wing Lake, now in the RM of Shellmouth-Boulton just southeast of Roblin — where they ran the local post office.

The local history book says Howell died at age 74, after suffering several strokes in 1971, followed by her husband in 1981. They had no children and both are buried in the Roblin Cemetery.

● ● ●

Seaford, England is a long way from home for a guy born and raised on the Manitoba Prairies.

Seaford Cemetery is a picturesque spot in the coastal southeast England town about 100 kilometres south of London and east of Brighton.

Here, for almost 100 years now, McCrae has lain accompanied by 252 other First World War soldiers of the Commonwealth, 191 of whom were Canadian. There is no Canadian War Memorial on the grounds.

Like all of the other Canadians, McCrae’s white Portland-stone marker has a engraved maple leaf at the top, a cross towards the bottom and his name, rank and the same registration number, 718793, that was at the top of his Attestation Paper he filled out two years before.

There is a large Great War Cross of Sacrifice looming above the graves and a stone chapel is behind.

Photographs of the time show piled dirt and wooden crosses at fresh graves, but a century later the ground is flat with cut grass and perennial plants in front of each gravestone.

McCrae’s white tombstone looks new, and it’s not an illusion. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission constantly monitors the graves of soldiers, both here and in cemeteries in France, to ensure they are in good condition. If not, they either re-engrave them or they are replaced.

Back home in Manitoba, three different communities honour McCrae for his First World War duties. His name is inscribed on not just one, but three, community cenotaphs in Gladstone, Roblin and McCreary.

He is also listed in Roblin’s local history book, along with all of the community’s other First World War soldiers. Asterisks appear after the names of people who didn’t return.

There’s an asterisk after McCrae’s name.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.