Mr. Big sting didn’t obtain confession

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/03/2018 (2827 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

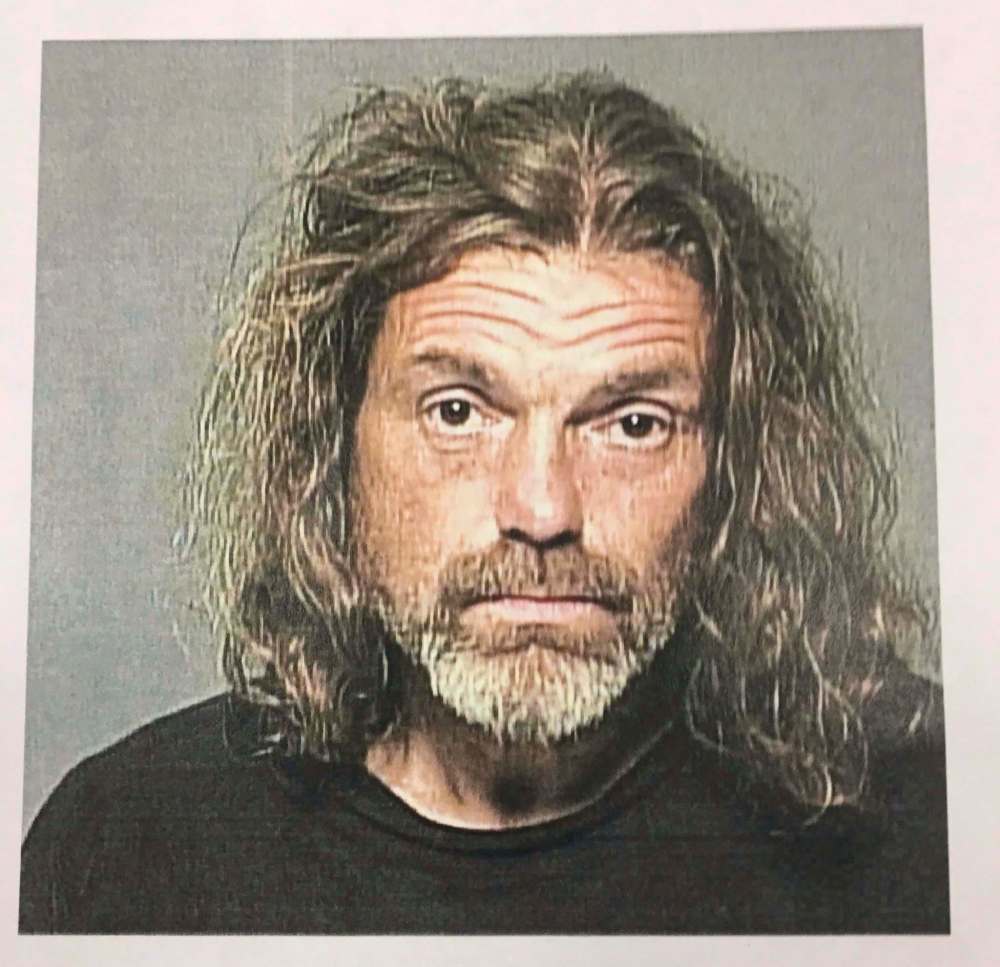

The man who was acquitted of killing 15-year-old Tina Fontaine did not confess to undercover police officers during a Mr. Big sting against him, the Free Press has learned.

“The Mr. Big operation did not produce a confession,” confirmed Crown prosecutor James Ross, who handled the case through to the completion of the three-week trial last month. The jury acquitted Raymond Cormier, and Manitoba Justice announced this week the Crown’s office won’t appeal.

Ross spoke highly of the police work that went into Cormier’s case.

“The police investigation was thorough, comprehensive and well-conducted,” Ross said.

The jury that decided Raymond Cormier was not guilty of second-degree murder in the teen’s 2014 death didn’t hear any details of the Mr. Big portion of Project Styx, a six-month undercover investigation by the Winnipeg Police Service. It also involved setting up a public housing apartment for Cormier to live in, wiretapping the place with secret probes to record his conversations and equipping an undercover officer with a body-worn recording device as he posed as Cormier’s neighbour.

The police planned 62 different scenarios in which undercover officers interacted with Cormier, ranging from his “neighbour” saying hello to Cormier in the hallway, to giving him odd jobs to make some cash. One of those scenarios, which played out at the Logan Avenue apartment block, involved a female undercover officer made up to look bloodied and beaten. She posed as an unconscious victim of domestic violence, and Cormier saw her body being carried into a truck and taken away. Police wanted to measure his reaction to seeing a dead body being disposed, but they couldn’t determine his reaction.

While the scenarios culminated in undercover officers flying Cormier to Vancouver for the Mr. Big operation in B.C., none of that was part of the Crown’s case against Cormier.

The controversial technique, developed by RCMP in B.C. in the 1990s, involves undercover officers staging crimes to pose as a criminal organization and offering the suspect odd jobs and money to gain their trust.

The suspect is groomed to be part of the organization and is eventually asked to meet with the crime boss, “Mr. Big,” in a room police equip with secret video cameras to record an expected confession. The suspect is told they must confess to a crime as a way to prove themselves. They are sometimes assured the group can protect them from punishment or destroy evidence that would link them to the crime.

In Cormier’s case, police ended the undercover investigation without securing a confession. They arrested him and brought him back to Manitoba to face the murder charge.

The Crown didn’t use the Mr. Big evidence in court, meaning details of the Mr. Big sting aren’t public.

More oversight needed: professor

The case is an example of the need for more oversight of police techniques, says Kate Puddister, a University of Guelph political science professor who has studied Mr. Big techniques in Canada.

In a 2012 study, she found there is very little oversight of police use of Mr. Big operations, particularly when evidence of them isn’t brought up in court.“If the public doesn’t have confidence in the criminal justice system, the system ceases to function. If there’s no confidence, then there’s no perceived legitimacy in the processes. That’s pretty detrimental to society.”–Kate Puddister

“It’s really this black box. Unless it comes into court or the media gets wind of it and reports on it, we don’t know. That’s what we found in our research: there’s no public reporting of this. The oversight from the civilian oversight bodies for various police forces don’t have reports on it unless someone complains,” she said.

Puddister said the public needs to be informed about police investigations, even undercover investigations, to hold police accountable and have faith in the justice system.

“We choose to be policed. We police on the notion of consent, so we hold the police to a particular standard. And if they’re not going to engage in investigations in a way that we think is right, it’s going to be pretty difficult to have confidence in the criminal justice system and confidence in the investigation and confidence in the outcome. If the public doesn’t have confidence in the criminal justice system, the system ceases to function. If there’s no confidence, then there’s no perceived legitimacy in the processes. That’s pretty detrimental to society.”

Cormier filed LERA complaint

Cormier complained about getting caught up in a Mr. Big operation, and the Winnipeg Police Service acknowledged the tactic was one piece of its investigation against him. He launched a Law Enforcement Review Agency complaint against the police service, alleging police fabricated evidence.

Part of his concern, court heard during his trial, was that police gave him fake identification bearing the name Sebastian during their undercover operation. Cormier did not want police to use that fake ID to connect him to the name Sebastian, a name Tina used in a 911 call to police before she died in August 2014.

He admitted in a prior interview with police, though, that he used to “tell everybody my name’s Sebastian.”

Ultimately, the Crown relied on what it considered to be the strongest evidence against Cormier: wiretap conversations in which prosecutors argued he admitted to killing Tina because he found out she was underage and didn’t want to be considered a pedophile for being sexually interested in her.

Cormier’s lawyers offered different interpretations of the wiretaps and argued Cormier didn’t kill Tina or have sex with her.

No authorization needed for Mr. Big

Police don’t need judicial authorization from the courts to use Mr. Big techniques.

Evidence that is gathered during a Mr. Big operation is presumptively inadmissible in court, based on a 2014 Supreme Court decision, unless the Crown can prove the evidence is important enough to outweigh the prejudice to the accused, who will be shown to have participated in criminal activity along with undercover police.

The Supreme Court’s ruling didn’t ban the practice, but it did restrict how Mr. Big evidence is used in court.

Despite those restrictions, police are likely to keep using Mr. Big techniques if they consider them necessary, said University of Manitoba law Prof. Amar Khoday, who has studied controversial Mr. Big confessions.“I think they’ll probably continue to happen, but with a mindful eye that there are limits to how far the police can go.”–Amar Khoday

“I think they’ll probably continue to happen, but with a mindful eye that there are limits to how far the police can go, and if they go beyond a certain point that the Crown believes this might run afoul of the (2014 Supreme Court decision), then they might have to keep it out of evidence and go with what they have.

“In some cases, that may be other evidence that they feel can support a conviction, and in other cases, it may be that they don’t have it, and they have to decide whether or not to pursue the case,” he said.

“I think there’s an argument to be made that huge public resources are spent on these things, and there is a fair space for the public to debate whether these things should happen or not.

“I mean, I have no doubt there’s a segment of society — maybe a huge segment of society — that says it’s perfectly fine that these things happen within reason, and another side that will say no, these things cost too much money and there’s too much of a risk of wrongful conviction or a false confession leading to a wrongful conviction.

“But I think these tactics are open for public scrutiny, especially since public funds are spent on it.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.