Debate still rages over proposed national park

First Nations want Lowlands to be protected area

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/05/2017 (3135 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

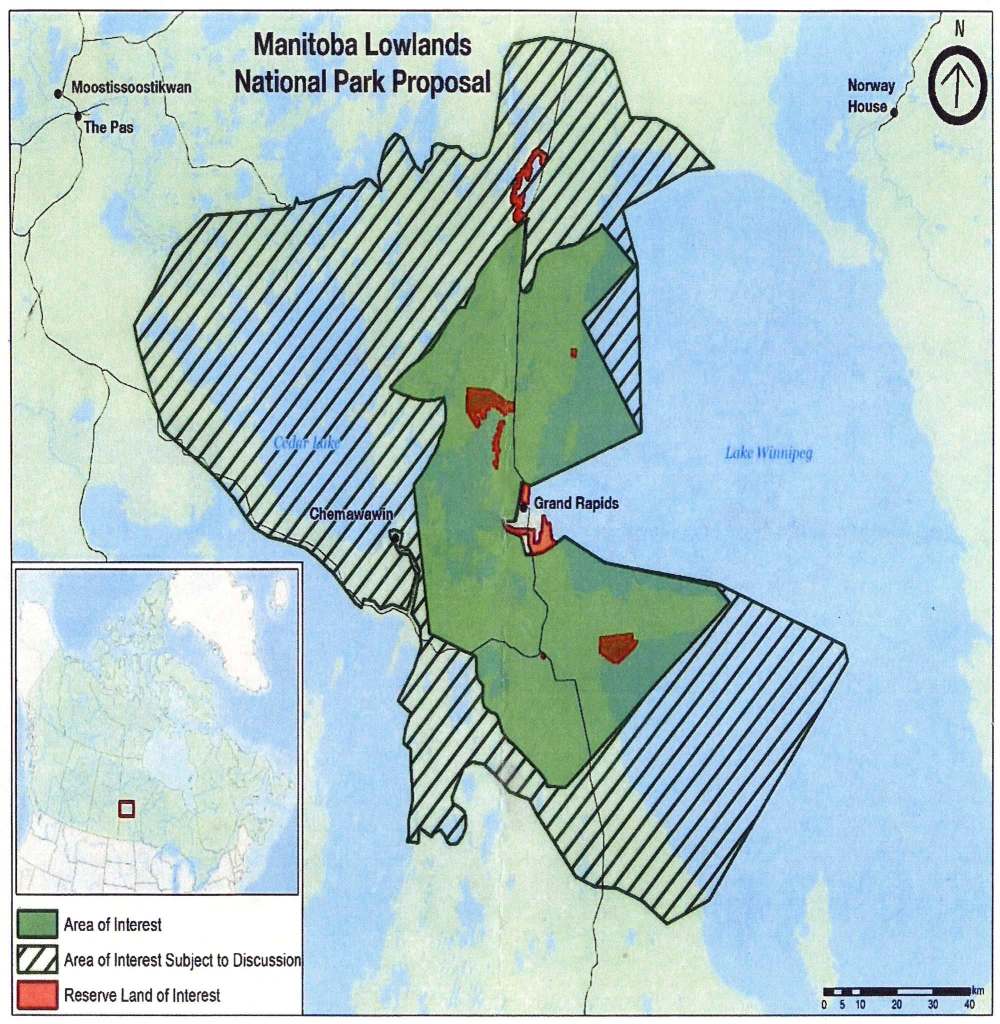

The proposed Lowlands National Park — killed off by opposition from indigenous leader Ovide Mercredi a dozen years ago — has risen like a zombie, and people in the province are scrambling to find out what it means.

The federal government surprised everyone in its recent budget by resurrecting the proposal for a 4,400-square-kilometre Lowlands National Park on the northwest shores of Lake Winnipeg.

The massive park would protect a unique ecosystem including wetlands, forests, beaches, karst caves, sinkholes, sand spits and lakefront cliffs.

Mining interests say the park threatens the futures of Thompson and Flin Flon because it would cover the southern extension of the Thompson Nickel Belt. That’s where those mining centres expect to obtain future feeder ore.

“We know there’s economic ore down there,” said Ruth Bezys, president of the Manitoba Prospectors and Developers Association.

It would not only jeopardize people living and working in those cities but future royalties and tax dollars for the province, she said.

First Nations wondered why they weren’t consulted, although some preliminary talks have begun since the announcement, said Heidi Cook, the Misipawistik Cree Nation (Grand Rapids) band councillor in charge of its land portfolio.

Instead of a national park, First Nations want an “indigenous protection area model” where they retain greater control, including harvesting rights, Cook said, adding that Ottawa is starting to listen.

“If it’s an indigenous-protected area, it puts more land and management of that land back in hands of the people who have been here for generations,” Cook said.

Mercredi, now past president of the provincial NDP, deferred comment to Cook.

The park idea was last advanced in 2002 by the Liberal Jean Chrétien government but was killed by First Nations opposition led by Mercredi. The park would directly affect traditional territory of Cree bands Misipawistik, Chemawawin, Mosakahiken and Norway House.

While Parks Canada said the park boundaries are negotiable, some people involved in the first go-round said they’ve heard that before.

Parks Canada said its goal is to establish a system of national parks that represents each of Canada’s distinct natural regions. The Manitoba lowlands is a natural region that remains unrepresented.

These are the early stages of discussions with provincial officials on the feasibility of the park and there will be consultations with the public, stakeholders and indigenous peoples, Parks Canada said in an email exchange.

“The government is committed to developing a system of national heritage places that recognizes the role of indigenous peoples in Canada and the traditional use of these special places,” Parks Canada said.

Ron Thiessen, executive director of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Manitoba Chapter, said the region is very valuable in terms of indigenous culture and the environment, including wildlife populations.

“Whether it is a proposal for a national park or another form of protected areas, it must be developed fully with affected indigenous nations and must have their full consent before being approved,” Thiessen said in an email exchange.

No one expects a quick resolution but rather years of negotiations. Bezys said lingering uncertainty over the territory will scare off mineral exploration in the province.

“If everything’s preserved, you’re taking away opportunity for economic wealth for this province,” Bezys said. “We want a lot of free health care, we want a lot of social services, but we need money, and our taxes can’t carry all these things.”

The provincial government did not provide a response after being contacted by the Free Press.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca