The night the roof came off Heritage Classic revives memories of joy in Jetsville after double-OT playoff goal in 1990 against the Oilers By: Randy Turner Posted: Last Modified:

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/10/2016 (2891 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On April 10, 1990, Dale Hawerchuk was driving to work, not unlike any other time during his nine-year, Hall of Hame career with the Winnipeg Jets.

It was a Tuesday, a little cooler than average for the time of year.

But Hawerchuk wasn’t thinking about weather. The Jets captain had his mind fixed on the Edmonton Oilers and the immediate future: Game 4 of the Smythe Division semifinal versus the arch-nemesis Edmonton Oilers.

For once, Hawerchuk wasn’t concerned about the past; how the Oilers — the dominant, gifted force of the National Hockey League — had so often used the Jets as a stepping stone to greatness.

The Jets and Oilers had met four times previously in the playoffs. And four times the Oilers swatted Winnipeg aside and went on to capture the Stanley Cup.

This time was different. The Jets had shocked the Oilers 7-5 in Edmonton in Game 1. After losing Game 2 in overtime (3-2), the Jets responded in Game 3 back at the Winnipeg Arena with a 2-1 victory.

Now this, a glorious opportunity to exorcise the ghosts of Oilers past.

“We just felt good,” Hawerchuk recalls more than 26 years later. “We can play with these guys, we can beat these guys. This was our chance.

“This was our turn, our time.”

Hawerchuk’s longtime teammate, Doug Smail, who wore a Jets uniform from 1980 to 1991, was channelling his captain that day.

“I do remember driving to the rink… thinking, ‘This is ours,’” says Smail, now 59. “It was time for us to get one. We were humbly confident we could go all the way and win the Cup that year.”

After a slow start, the Jets finished the season with a flourish at 37-32-11. The Oilers went 38-28-14 but were not the same unstoppable force that had sipped from four Cups between 1984 and 1988.

The Great One had been shipped to L.A. Perennial Norris Trophy candidate Paul Coffey had been dealt to Pittsburgh. Goaltender Grant Fuhr, at the tail end of a stellar career in Edmonton, was injured.

“That year, because Gretz (Wayne Gretzky) was gone, a lot of people questioned if we were ever going to win again,” says then-Oilers defenceman Charlie Huddy, now an assistant coach with the reincarnated Jets. “So we had a little bit of extra motivation going into those playoffs. He was a huge, huge part of our wins.”

Not much was expected from either club in the post-season. With five Canadian teams qualifying for the playoffs, the powers that be at Hockey Night in Canada had decided to broadcast the series only in Manitoba and Kenora.

The HNIC crew in Winnipeg that night featured the late Don Wittman doing play-by-play, along with analyst John Garrett. Winnipeg’s own Scott Oake was the host.

“Everything was about distribution,” Oake says. “When you work on a series, you want it to be the big one that was seen by the biggest audience.

“So we started joking around and calling ourselves the D Team. And John Garrett actually had T-shirts made up saying, “The D-team: seen only in Manitoba and Kenora.”

(Of course, the series was also broadcast in Edmonton. But why ruin a good story? Or T-shirt, for that matter?)

Regardless, Garrett notes: “It was post-Gretzky. People didn’t really care who won, and they didn’t think the Oilers would do anything even if they won that series.”

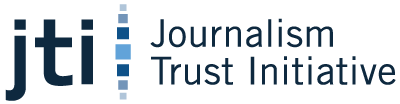

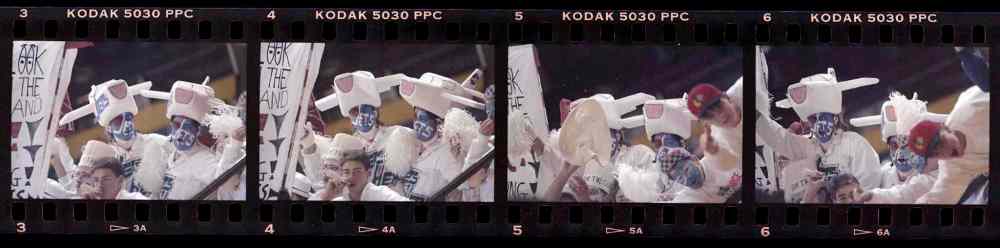

By the time the puck dropped in Game 4, however, Jets fans didn’t care who else was watching. There were 15,572 of the faithful jammed — hundreds of whom had paid to stand — into Winnipeg Arena that night, and virtually every one of them was clad in white: T-shirts, jerseys, jumpsuits… you name it. It had become known throughout North America hockey circles as the Sea of White.

“If it was ever tough at that time of the year you stepped out on that ice… those fans,” Smail says. “I remember the first time they did it (in 1987), it almost made me seasick, with all that white. I remember that vividly because you could feel the anticipation of the fans, as well.”

The old barn in the post-season was indeed a formidable environment for the visitors, Huddy concedes.

“It was a great building… how loud the fans were,” Huddy says. “Once you got in the playoffs it took off from there. It was a tough, tough building to come into.”

Just beneath that thunderous expectation, however, simmered years of deep-seated angst. This was the eighth playoff appearance for the Jets since entering the NHL in 1979. They had only won two previous series, both against the Calgary Flames (1985 and 1987).

In the four series versus the Oilers, the Jets were a combined 1-18. They had never led.

So what was the general attitude of the Jets towards the team that had skated past them en route to four championships?

“I hated them,” former Jets defenceman Dave Ellett says without a trace of hesitation. “I hated losing. But the other side is you respected how good they were and they knew how to win, especially in the playoffs. You were always going to get their best.

“But, yeah, I hated losing to them, hated to have to shake their hands after losses. Hated it.”

This was the baggage crammed into the Jets’ psychological terminal that April. The fans felt the pain, too.

It’s why Smail recalls the atmosphere in the Jets dressing room prior to Game 4 as being “quietly confident. And terribly, terribly frustrated at losing.”

“We thought we were there in ‘85 and a couple years later,” he says from his home in Denver. “We felt we were maybe a player or two away, but we could upset them. I think we were a lot closer than people believed. We were a lot better hockey team than the world knew because the Oilers were in our division.

“You don’t want to think about it at the time, that you’re playing those types of characters… all-world, all-time teams. But it doesn’t escape your mind. They were that great. But we were one of the best teams nobody ever knew.”

And maybe that’s been forgotten with the passage of time, and the loss of a franchise: the Winnipeg Jets of the mid- to late-1980s were the Little Engine that Never Quite Could. When the Jets and Oilers meet this weekend on Heritage Classic ice at Investors Group Field — the old veterans on Saturday and the next generation Sunday — it will highlight a rivalry that, on paper, was never really a rivalry at all.

Which only underlines that what unfolded in the white-coated din of the Winnipeg Arena on the night of April 10 is considered the most cathartic and memorable event in Jets 1.0 history.

It began with Jennifer Hansen, as always, signing the national anthem. She was wearing a white tuxedo.

The crowd was already in full throat.

The Oilers struck early, however, when Petr Klima was left alone in front of Jets’ netminder Bob Essensa, and shovelled home a feed from Kelly Buchberger to make it 1-0. Jets forward Mark Kumpel, an AHL/NHL journeyman who played for Canada’s 1984 Olympic team, tied the game 1-1 a short time later.

The Oilers swarmed the Jets for most of the first period, but Essensa, making his second straight start after winning Games 1 and 3, was the difference.

“All sorts of pressure by the Oilers,” Wittman told the limited TV audience after one furious Edmonton push.

“And Bob Essensa is keeping the Jets in this game,” added Garrett.

Only seconds later, Hawerchuk sprung away on a two-on-one, feathering a perfect pass to a streaking Pat Elynuik — the Jets’ leading goal-scorer that season, along with Paul Fenton (32) — who put Winnipeg ahead 2-1.

With the building still awash in bedlam, just 22 seconds later, Jets’ fourth-liner Doug Evans made it 3-1. The Winnipeg Arena was shaking, a mixture of delirium and disbelief.

Oilers head coach John Muckler called a time-out. The game settled down.

In the second period, Oilers defenceman Steve Smith scored a short-handed goal to pull Edmonton to within 3-2. The Jets were in control.

But you don’t win four Stanley Cups by taking prisoners.

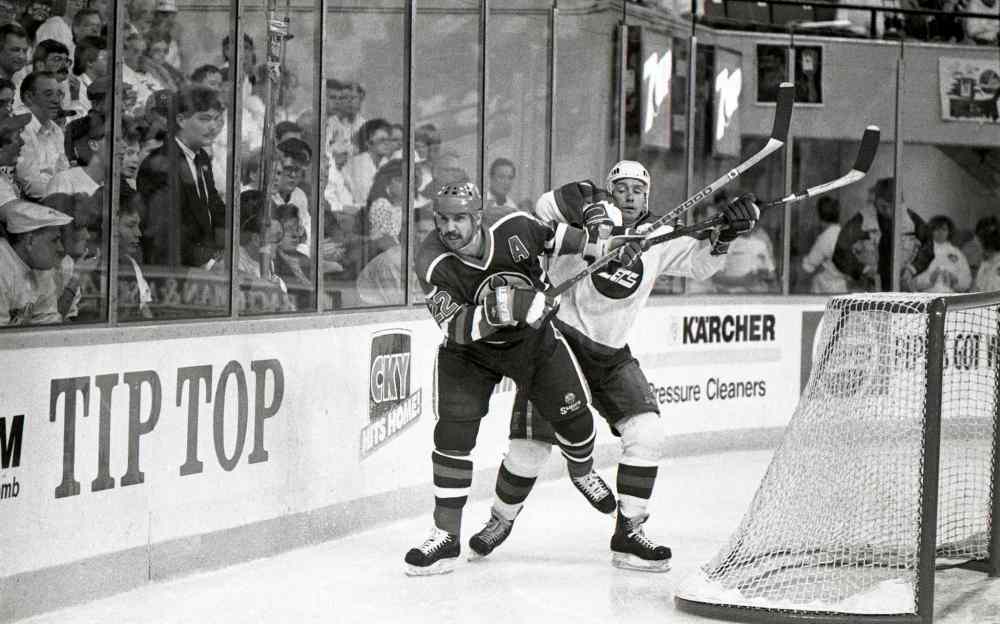

Midway through the second period, future Oilers hall of fame forward Glenn Anderson came flying down the right side, driving hard towards the Jets’ net with the puck. Anderson left his feet at the goal-mouth and slammed into Essensa.

Anderson not only fell hard on the Jets’ netminder, he proceeded to scrape off his mask and drag his knee over his head, the slow-motion replay clearly showed.

Essensa was dazed, prone on the ice.

“It knocked me for a loop,” recalls Essensa, now the goalie coach of the Boston Bruins. “I was goofy for a little bit. I remember (the trainers) coming out and asking me questions, and one of the ones that I didn’t get was, ‘What’s the score?’”

There was no protest. Not even a scrum, much less a penalty.

“Nowadays there’s 15 different cameras and you’re not going to get away with anything,” Essensa says from his Boston home. “If they did get it on camera it’s not like they had to go in front of an NHL review board the next day.”

For the record, the score was 3-2 Jets. But only a few minutes after backup Stephane Beauregard was forced into the game, he missed a softie from Esa Tikkanen that knotted the game at 3-3 with 35 second left in the second period.

Essensa knew. In the bowels of the old arena, he heard the crowd moan.

The third period was scoreless as Beauregard rebounded from a shaky start.

Overtime loomed.

But there were no rah-rah speeches in the locker room, particularly from Jets’ buttoned-down head coach Bob Murdoch who, like GM Mike Smith, was far more professorial than overtly passionate.

Hawerchuk wasn’t interested in talking much, either.

“Sometimes it’s more quiet (in the dressing room) than people think,” the ex-captain says. “Everybody knows what they gotta do. If you don’t know by that time you’re in trouble.”

The first overtime period ended without a winning goal, torquing the tension. It was now the longest game in Jets history, but only the Queen — her stoic portrait hanging from the rafters — seemed unfazed amid the drama.

On the bench, Hawerchuk kept thinking, “We’re going to win this. It’s just a matter of when.”

Only seconds into the fifth period, centre Thomas Steen blocked a dump-in by Edmonton’s Reijo Ruotsalainen just outside the Jets’ blue line, gobbled up the puck, and darted behind the Oilers’ defence — only to be hauled down by the Finn when he appeared to have a clear path to goaltender Bill Ranford… and pure joy beyond.

Referee Dan Marouelli immediately called Ruotsalainen for hooking. It was at the 1:05 mark of the period.

At that point, the Jets had nothing to show for seven power-play chances earlier in the game.

The faceoff after the penalty call was to Ranford’s left. Steen lined up for the draw against Oilers centre Craig MacTavish. Ellett and Freddie Olausson were on the Jets’ blue line.

The plan was for Steen to win the draw and kick the puck back to Ellett — which is exactly what the understated Swede did.

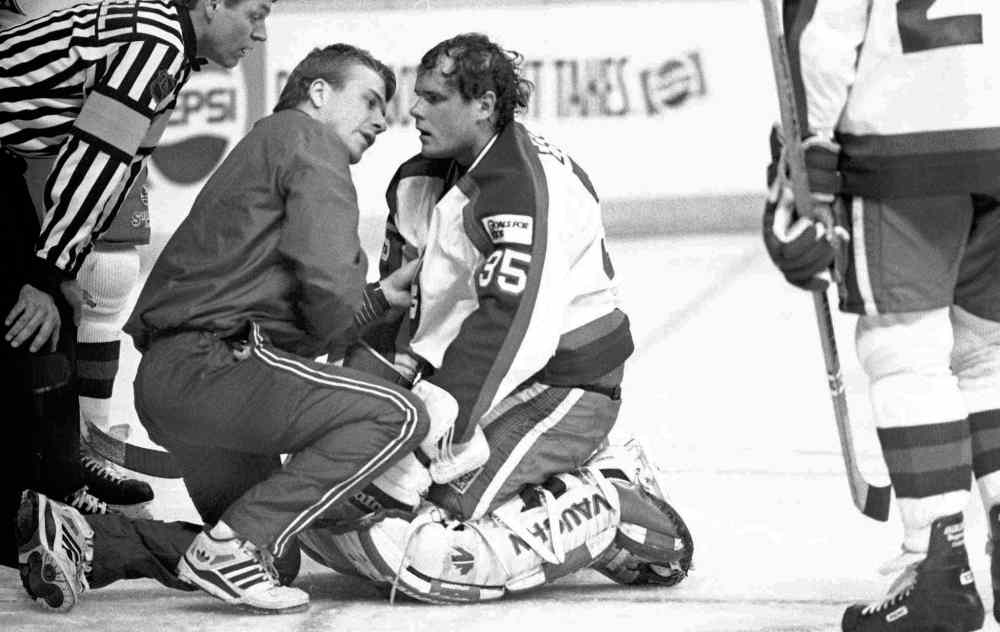

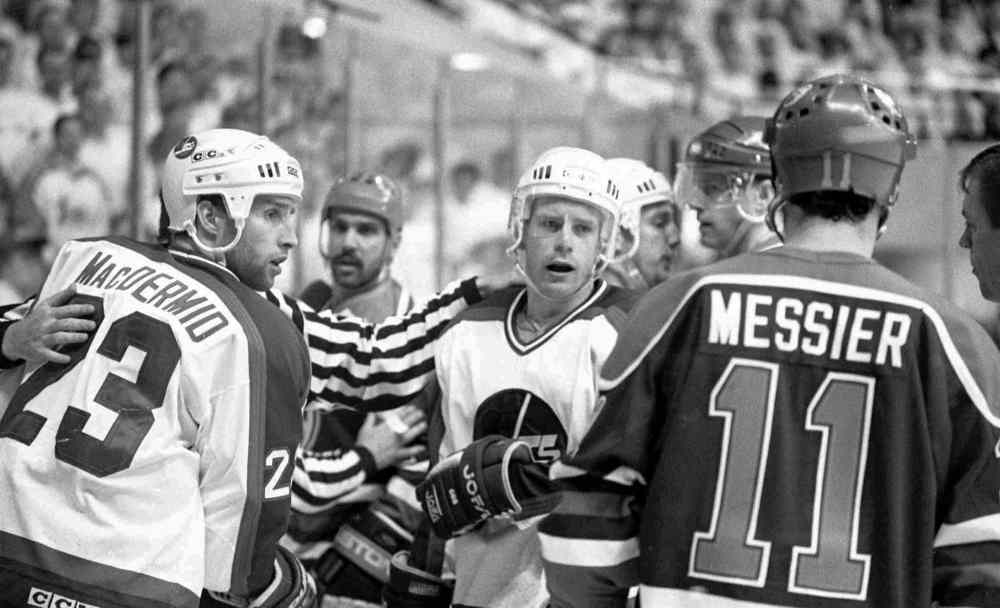

Steen tied up MacTavish in the circle. Legendary Oilers winger Mark Messier hesitated, electing not to charge the point. Ellett crept in a few feet and…

“Off the post and in,” Oilers forward Craig Simpson recalls ruefully. “A beautiful shot.”

For those who witnessed the moment, the scene — the sheer cathartic release of more than 15,000 heretofore tortured souls on Maroons Road — was unprecedented. And deafening.

“It’s the loudest I’d ever heard the place, Oake says. “I thought the roof would blow off. I cannot recall a more euphoric moment in Jets 1.0 history.”

Veteran Winnipeg TV broadcaster Joe Pascucci was standing in the press box balcony, looking down on the drama unfolding below.

“When Ellett scored that goal,” Pascucci remembers, “the sound waves literally pushed me back a couple of steps.”

Ellett’s blast had beaten Ranford low to the stick side. He had vanquished the hated Oilers.

“Just pure excitement and jubilation,” Ellett says when asked to describe it now. “The roof actually went off that building. It was really unbelievable to be honest with you.

“For something that wasn’t a series clinching victory there was a lot of emotion in that building, and the city.”

Smail felt “exhilaration, with some relief.”

“Even though it was just one notch in the belt that you have to fill up with notches to get to the Stanley Cup… it was a big notch,” he says. “It was the biggest notch of my Winnipeg Jets career.”

The Jets, of course, mobbed Ellett. And the crowd’s celebration seemed to last forever.

“These fans,” Wittman said, trying to be heard over the roar, “just don’t want to go home.”

Ellett tried to do a radio interview under the stands.

“We essentially had to stop the interview because I couldn’t hear the questions they were asking me,” he says. “The fans, I don’t know how long they were standing, but they didn’t want to leave. They were savouring the moment as long as they could.”

One fan, in particular, wasn’t about to leave, either. He was a spectator in the corner, at the end where Ellett scored.

Does he still remember that night?

“Vividly,” Mark Chipman says. “I remember it like yesterday. I remember how tense it was in the building. You’re up two-one (in the series) and it’s a swing game. I remember the draw being won so clean and kicked back and… bang! Honestly, I thought the roof was going to go off. It’s the loudest I ever experienced.”

Just over 20 years later, Chipman would buy the Atlanta Thrashers, along with co-owner David Thomson, and bring the team to Winnipeg, finally healing the still-open wound the city had been nursing since the Jets had loaded up the moving vans and relocated to Phoenix after the 1996 season.

Oake, meanwhile, thinks it fitting that Steen — who played all 14 of his NHL seasons in a Jets uniform — was a key part of the winning goal.

“People refer to that as the greatest goal in Jets 1.0 history and they’re probably right,” the broadcaster says. “But I don’t think Thomas Steen gets enough credit for it.

“I thought, ‘Way to go, Thomas.’ He was a great player for the Jets for a lot of years.”

But here’s the thing about happy endings: Ellett’s goal was scored at exactly 11:42 p.m. As the pandemonium reigned, it was literally about to strike midnight in Jetsville.

First, when the Oilers went to board their bus, running the gauntlet of giddy Jets fans who would often congregate after games at the east side entrance of the building, words were exchanged between a fan and Edmonton assistant coach Teddy Green — a Manitoba-born old-schooler who had toiled four seasons on the WHA Jets blue line.

“It almost turned ugly,” Ranford says. “I think that ignited our passions even more. Some words were passed. Everybody got together in a little scrum. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed. But I think that just gave us more ammunition heading into Game 5. It was something else that made us want to return to Winnipeg one more time (for Game 6).

“It was very heated back then,” he added. “I mean, it was a huge rivalry. That’s what’s so ironic about doing this (weekend’s) outdoor game. I don’t think people realize when you always had to come out of the Smythe division, it created those good rivalries. You’re going up against the Winnipegs and the Calgarys every year. Each team had a hate-on for each other.”

The dust-up outside the arena only antagonized a veteran, proud team that was seething over the words of Jets’ assistant coach Alpo Suhonen who, after Winnipeg’s Game 1 victory in Edmonton, described the Oilers as “arrogant” and “confused.”

“A lot of times that bulletin board stuff is overblown in terms of having much of an impact,” says Simpson, who tied Messier in playoff scoring that year with 31 points. “But I think that slight, I think anybody in the Winnipeg organization would say, came at the worst possible time. That sort of furthered our resolve as a group.

“I know when you win a series you can point to something like that. But you didn’t need to tell Mark Messier and Glenn Anderson and Jari Kurri and Kevin Lowe… that our team was washed up and a little too slow.”

What happened next? Well, the Oilers happened. This time from the graveyard, not quite the grave.

We’ll spare Jets fans from rehashing the sordid details. Suffice to say the “arrogant” and “confused” Oilers stormed back to win three straight.

And the next series. And the next, before dispatching the Boston Bruins in five games to win the Cup. Again. Ranford, who made his playoff debut with the Oilers, won the Conn Smythe trophy as the post-season MVP.

Turns out, Game 4 — which produced the most joyous victory in the history of the franchise — was just the wake-up call Edmonton needed.

It didn’t help that Murdoch dithered on who to start in net after Game 4. Or the inexplicable decision to yank Hawerchuk from the power-play later in the series.

The more experienced, battle-tested Oilers simply refused to beat themselves.

“The key is for the guys who lost that game is what do you do to prepare yourself for the next one?” says Simpson, who was 23 at the time. “That’s always what you have to focus on; not what happened but what are you going to do to make the future different?

“That series helped us get back to the top and win the Stanley Cup.”

More than quarter of a century later, the Jets who were there, now well into middle-age and long since retired, haven’t forgotten, either.

Hawerchuk is philosophical about his last game in a Jets uniform. The franchise’s all-time leading scorer was traded that off-season to the Buffalo Sabres in a deal that brought all-star defenceman Phil Housley and a draft pick that turned out to be future star Keith Tkachuk to Winnipeg.

“I don’t know,” Hawerchuk says, when asked if the 1990 series still stings.”It is what it is. You have to move on. We were in a tough division. We were in an era where there wasn’t a salary cap… we were a low-budget team. It would have been a great upset if we would have won it.

“You think about it, for sure. When you lose you’re disappointed and when you see them winning you’re thinking, ‘Man, that could have been us.’”

It’s far from fresh, but Ellett wears an emotional scar from the aftermath of the biggest goal in his 16-year career.

“At the time it was a real thrill, a big moment in my career, and my team,” he says. “But over time it became meaningless to me because we didn’t win the series.

“I shouldn’t say meaningless. It’s a good memory for me now. But… you know, I think for everybody involved… I’ve had a lot of playoff series, but that was the most disappointing one.”

Essensa, meanwhile, still chides himself to this day for the game-winning goal he surrendered to Kurri — a slapper over his blocker — in Game 6.

“It was probably one of those teams if you look back I don’t even know if we knew how good we were,” he says about one of the best teams nobody ever knew. “To get the eventual Stanley Cup champions down in a hole 3-1… who knows if you get through that series? Maybe you could rewrite the record books. But that’s hockey.”

No, it’s not pretty. In fact, from a Winnipeg standpoint, the Jets-Oilers heritage isn’t classic at all. But it’s real, and it runs deep.

Who knows? Perhaps, one day the Winnipeg Jets will finally win a Stanley Cup. Maybe they’ll even defeat the Oilers along the way.

But until then, there’s always April 10, 1990. The night the roof came off.

The night Jets fans, for once, could almost taste it.

The night no one wanted to go home.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @randyturner15

Archive photos by Jon Thordarson

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.