The kids are all right

Northern agency asks: if it’s the parents who are the problem, why seize the children?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/12/2015 (3331 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

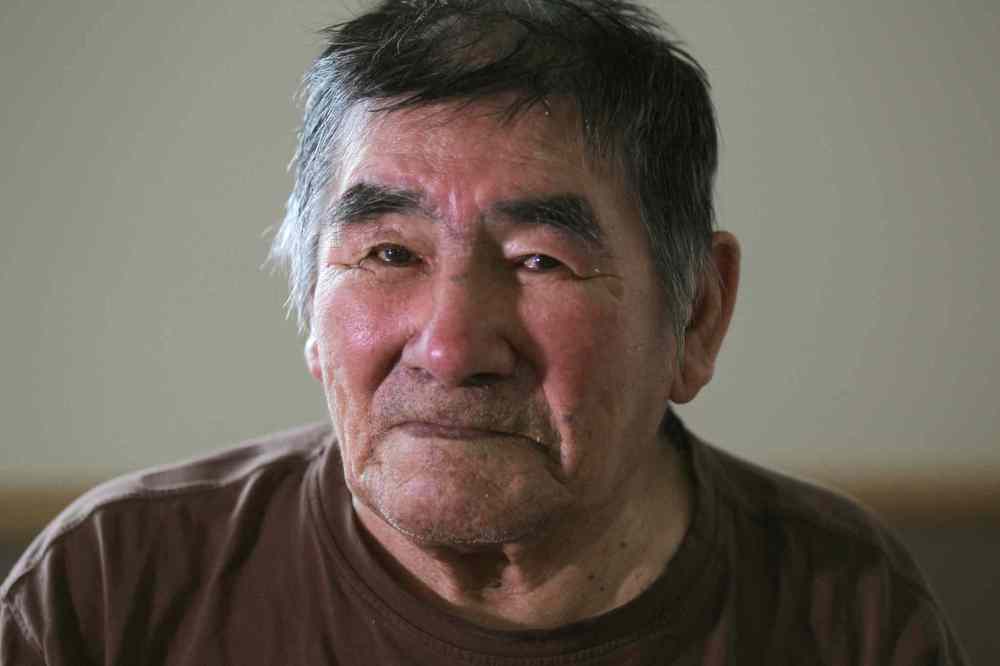

NISICHAWAYASIHK CREE NATION — More than a decade ago, shortly after Felix Walker was hired to manage the wellness centre in Nelson House, he got a gentle chiding from elders about the way Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation was running child welfare.

“It kind of felt like I was in court,” laughed Walker of the meeting in the wellness centre’s busy, log cabin-style lounge, where the always-full coffee pot draws a crowd. “One elder, it was Joshua Flett, said, ‘The children aren’t the problem. You need to start leaving the children at home. Move the supports into the home and remove the parents.’ ”

At the time, apprehensions of children were so common that parents would have their kids waiting with packed bags when CFS arrived, as though apprehension was an inevitability to be met passively. As with generations of children lost to residential schools, Walker said that epidemic of apprehensions damaged the spiritual core of the community, whose traditional social structure is built with children at the centre of the circle. The exodus of children to far-away foster homes left the same kind of open wounds for parents as residential schools, said Walker.

“If there was a kid in need of protection, it was apprehend, apprehend, apprehend. We said, ‘This is crazy. There has to be a better way,’ ” said Walker, the CEO of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre. (Nisichawayasihk was formerly Nelson House First Nation.)

“We asked, are we as an organization raising the next generation of kids? Because it should be families.”

That prodding from elders prompted a radical, two-pronged shift in the way Nelson House runs child welfare in the years after hundreds of files were transferred to the band’s new agency following devolution in 2003. First, the band created an integrated circle of care, where workers from every department at the wellness centre — public health, family counselling, child welfare, prevention, addictions — sit down with parents who’ve lost their kids and help create a plan to get things straightened out. Second, when social workers apprehend kids, a special band council resolution allows CFS to kick the parents out of the house instead of taking the kids away to foster care. That’s been the standard approach since 2013 and often, aunties or grannies are brought in to look after the children for a few months or longer, but the kids stay home and siblings stay together.

Where the parents go, is in some ways, not CFS’s concern. The approach, according to one mother who was removed from her home, made it clear she was the problem, not her kids.

“I didn’t want to leave,” said Dorothy, who recently got back custody of her large brood of children after four months. “I didn’t have anywhere to stay. I was bouncing from house to house.”

While social workers lived in her house and cared for her kids, Dorothy couch-surfed in three different places, including her brother’s home, where there was a lot of arguing, and her cousin’s home, where there was a lot of drinking. The nuisance of that helped Dorothy decide to take action.

(By law, the Free Press cannot identify children in care, and so is not using Dorothy’s real name.)

Last summer, Dorothy’s children were apprehended after she left them in the care of a babysitter for a day-and-a-half. It wasn’t the first time she lost her children, or the first time she was told to sober up.

“They gave me the last warning,” she said. “I don’t want my kids to get taken again.”

Dorothy went through a circle-of-care meeting, where she and a group of staffers from several departments at the wellness centre all sat around a table and discussed what she needed to get her act together and get her kids back. She took parenting classes, talked to a therapist and went for an eight-week alcohol-treatment program at the Medicine Lodge down the road. Occasionally, her kids would sneak in to see her. She got to return home in late fall after about four months away, and this time she hopes to remain sober.

If Manitoba’s aboriginal child welfare system seems like an unsolvable problem with too many indigenous kids in care and the process of devolution at an impasse, Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation’s double-whammy approach might offer a solution. It’s the only agency to see a significant and steady drop in the number of kids in care — a 33 per cent decline over the last six years.

Walker says the reserve has, at the time of writing, virtually no new kids in care who aren’t living in their own homes. As well, the number of kids from the reserve sent away to foster care has shrunk to 60 from about 220 a decade ago, and most of those involve kids with specialized needs.

The next task in keeping more kids at home is the construction this spring of 10, five-bed specialized foster homes for kids with serious troubles, kids who would normally be sent to Winnipeg for treatment at Marymound or Macdonald Youth Service at a cost of about $3 million a year to the wellness centre. That money can be better spent funding local group homes, which could employ as many as 100 people.

“Kids shouldn’t be going south for placements,” said Walker. “They shouldn’t be placed with complete strangers.”

Walker says only about five per cent of NCN’s child welfare cases involve abuse. Most involve neglect — mom is a great parent except for twice-a-month benders. Mom has several children and is getting no help from anyone and leaves the kids at home alone for a night, the way Dorothy did. Mom and dad are a young couple, former foster kids themselves, and their fights get violent when alcohol is involved. Those are problems that can be mitigated with addictions counselling, parenting programs, respite and the watchful eye of a social worker who is willing to find a solution rather than apprehend a child.

“If you put all the supports in place, is the child still unsafe? No? Then leave the family intact,” said Walker.

Nelson House, located on a collection of fingers that stretch into the Burntwood River, is home to about 3,000 people. An hour west of Thompson and close to the new Manitoba Hydro Wuskwatim dam, Nelson House is a comparatively prosperous band with stable leadership and few scandals.

But, it’s still clustered with a predictable collection of overcrowded homes, many covered in graffiti and plastic insulation paper, with Plexiglas for windows and muddy front yards. A shortage of housing is arguably the band’s biggest issue, one that complicates the child welfare puzzle. In the past, when the kids were removed from a home and the parents allowed to stay, the parents often started to party, wrecking the house and getting evicted. Then, when they got sober, they’d be unable to get their kids back because they had no place to live.

As part of the wellness centre’s approach, Walker’s staff often do some creative budgeting, using money that might have funded a foster home to instead fix up a child’s home, replacing drywall, fixing doors and making the home safe.

Though the province and the Office of the Children’s Advocate praised NCN, Walker said its maverick approach has rubbed senior child welfare officials the wrong way, including the Northern Authority, which is supposed to oversee northern CFS agencies. Among the key issues is the province’s insistence its standards manual be followed, even when the standards are unrealistic on a reserve, and the use of the child welfare system’s central database of all kids in care, called CFSIS. Some First Nations, especially in the north and especially NCN, view the database as a surveillance system, one the province has no right to impose on reserves, where kids are in federal jurisdiction.

“I’ve essentially turned my back on the Northern Authority in the last six months,” said Walker. “Our relationships with our stakeholders has been strained.”

But Nelson House’s practice of removing parents instead of kids could be a model for an indigenous-run child welfare system across Manitoba, especially on reserves. Misipawistik Cree Nation is staring to remove parents, not kids, from homes, and other reserves, such as Opaskwayak Cree Nation, have asked for tutorials.