Key recommendations from Phoenix Sinclair inquiry yet to be implemented

Much work remains for CFS

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/12/2015 (3337 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The province is making slow progress on some of the biggest — and most expensive — child-welfare reforms recommended by the Phoenix Sinclair inquiry, nearly two years after it was released.

Little tangible change has been made to reform a complex funding model that still encourages Manitoba Child and Family Services workers to apprehend children instead of preventing family breakdown. There has been no legislative change allowing child welfare to extend services and funding to foster children until they are 25 years old.

It’s unclear whether any progress has been made to ensure a child in care has just one worker, instead of many. And average caseloads are still well above the 20-case cap recommended by commissioner Ted Hughes, who headed up the inquiry into Phoenix’s death and the state of Manitoba’s child-welfare system.

The province has introduced legislation to bolster the role of the children’s advocate, though the changes fell short of Hughes’ recommendations. And the province essentially rejected at least one of Hughes’ proposals — that anyone practising social work be registered with the Manitoba College of Social Workers, the profession’s new regulatory body. Instead, the province decreed only employees with the words “social worker” in their title need register.

The new college has argued that move dramatically weakens the new legislation and undermines Hughes’ recommendation. Still, the college has 1,800 social workers registered after just nine months of existence.

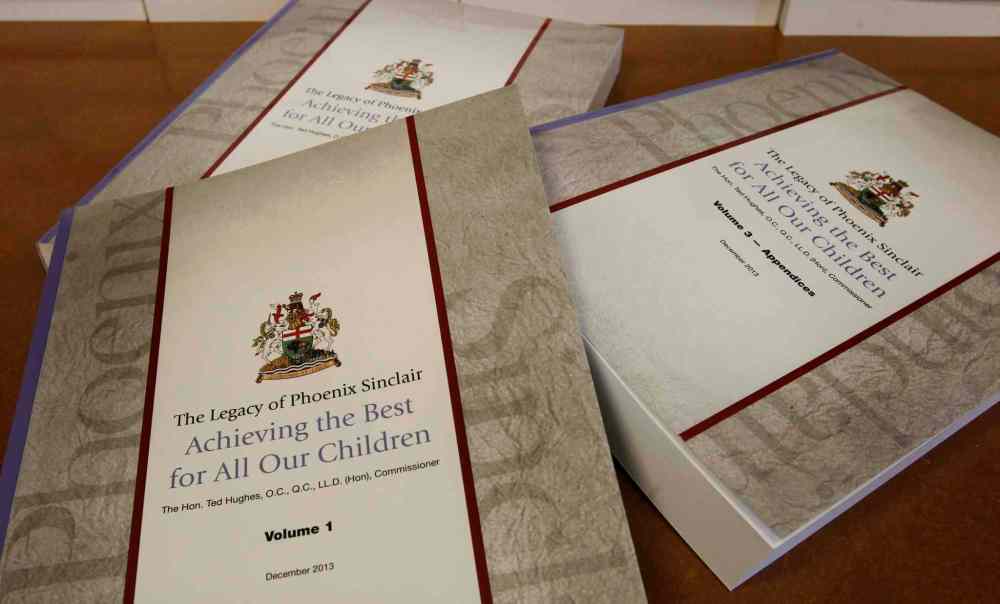

Phoenix Sinclair, 5, was tortured by her mother and stepfather and left to die in the basement of her home in Fisher River First Nation in 2005. When it was released in January 2013, the massive Hughes inquiry into Phoenix’s death cost $14 million and made 62 recommendations to improve the child-welfare system that let her down.

A spokeswoman for Manitoba government said more than half of the recommendations have been implemented. It’s not clear which ones.

“We continue to reach out and engage community leaders, non-profit organizations, other departments and other levels of government to ensure the memory of Phoenix Sinclair is honoured through the conscientious improvements to the child-welfare system,” the province said in a written statement.

In January, to mark the one-year anniversary of the Hughes report, the province released a 230-page implementation report meant to lay out scenarios for action on half of Hughes’ 62 recommendations (the ones not already underway). Among child-welfare sources, the document was widely seen as a stop-gap measure meant to buy time.

But Sherri Walsh, commission counsel to the Phoenix Sinclair inquiry, said she has a more hopeful take.

“I do think the government is working hard at responding to the recommendation,” said Walsh. “It’s clear this report has not been gathering dust.”

Walsh said the province is paying particular attention — as it ought to — to the recommendations that deal with poverty as a key root cause of family breakdown.

Manitoba children’s advocate Darlene MacDonald said her office is also watching key recommendations closely and hopes to issue an update of its own early in the new year.

Top recommendations on her radar include capped caseloads — the recommendation social workers have just 20 cases on the go, no matter if they are prevention cases or child-protection ones. Currently, funding is based on 25 child-protection cases per worker and 20 family-enhancement cases.

MacDonald said what’s also needed is a focus on stability for children in care. MacDonald said her office is still hearing too often from children who are moved from home to home, under the guidance of multiple workers.

“It’s still very much a crisis-oriented practice, which is very sad,” said MacDonald.

maryagnes.welch@freepress.mb.ca

wfpvideo:4656745726001:wfpvideo